Nobody down here but the FBI's most un-wanted.

Return to the complete X-Files index

Written by Chris Carter

Directed by Robert Mandel

Airdate: 10 September, 1993

The tricky thing about discussing a show like The X-Files nearly thirty years after it started airing is that we now know what sort of impact it was going to have on the world around it; and in the case of The X-Files, that impact was absolutely gargantuan. It's one of the major steps forward in the development of serialised TV in the United States: while it was one of four different shows the premiered around the same time that began to explore long-form storytelling (the others were Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Homicide: Life on the Street, and Babylon 5), none of the others had its broad popular and direct lines of influence: no X-Files, no Buffy the Vampire Slayer. No X-Files, no Lost - and Lost is the show most immediately responsible for the explosion of ongoing cliffhanger-driven television in the late 2000s and onwards. It had the exact perfect mixture of high rating and "hip" cachet to be regarded even while it was on the air as one of the decade's defining pop cultural artifacts. It is probably the single American TV program most responsible for normalising that idea that TV could actually look polished and cinematic, and was under no obligation to look cheap and rushed just because it was cheap and rushed (I would go so far as to say that you really do need to get to the 2000s to find anything else on TV in the U.S. that ever looked as good as The X-Files could manage week in and week out, certainly not outside of premium cable).

This importance is easy to overstate: serial television dated back decades before 1993, the year those four series all premiered their first episodes, all the way back to the first televised soap operas. Prime time soaps such as Dallas and Dynasty were instrumental in codifying the ground rules of ongoing television storytelling in the 1980s. Closer to home, The X-Files very clearly lives in the shadow of the 1990-'91 cult masterpiece Twin Peaks in virtually every respect, including its unusually handsome cinematic polish - the only then-recent work of pop culture that's more obviously an influence is the 1991 feature film The Silence of the Lambs (series creator Chris Carter always maintained that the primary influence was the 1974 series Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and that's obviously true. But while a nearly 20-year-old horror series that was such an underperformer in the ratings it couldn't even complete a full season might have inspired the writer, I have my doubts that it's what 20th Century Fox had in mind when they agreed to produce the show). Still, it's impossible to think of The X-Files as anything other than a major milestone in the history of its medium, and the culture surrounding it: this show is, among other things, the reason we use the word "mythology" to describe the backstory an ongoing series with dangling plot threads to lure us forward, and why we refer to "shipping" two characters (or, more dubiously, real-world people) whom we think would be a good romantic couple.

Again, the tricky thing is that I already know all of that. I knew it by the time I watched my first episode, in November 1996: by that point the show was firmly established as a major talking point and had accomplished most of its ascent from "good ratings by the standards of an hour-long drama on the perpetually embattled Fox Network" to "just flat-out good ratings". But it's not like the show was supposed to be all of those things. Well, not entirely: surely the creative team knew that they were putting something together that looked a hell of a lot better than anything else on TV. The point stands, though, when the show premiered in September 1993, it wasn't trying to define an era. It wasn't even trying to be a groundbreaking work of serial TV.

In fact, for something whose best-known influence is how it paved the way for long-form storytelling, The X-Files is secretly much more of an anthology show than just about anything else on the air at the same time. As it's basically a police procedural, the show had its formula down cold from the first episode: two FBI agents arrive to investigate a case, using their respective strengths, and they generally come up with a solution but are helpless to do anything about it, because almost without exception that solution involves a paranormal or extraterrestrial phenomenon. Which is where the anthology element comes in, because this turned out to be an extraordinarily flexible show: with a new location, new cast, new mystery, and often an entirely new genre, every episode of the show is basically a little standalone experience, united effectively only by the leads themselves, and by the general tendency towards horror or sci-fi, though even those weren't present in every episode.

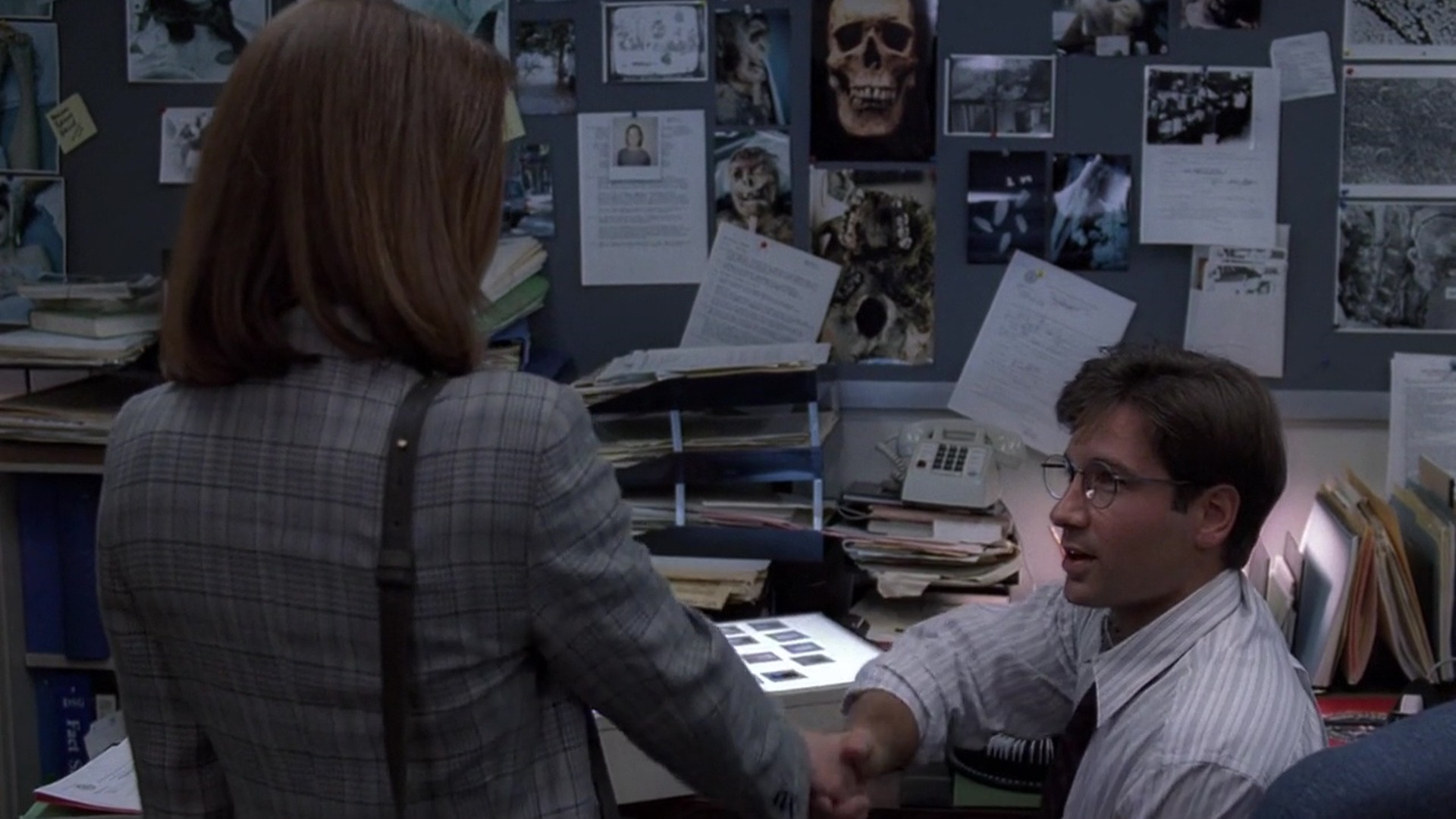

All of which is a lot of preamble to get us to a very simple point: there's a lot of crushing historical weight that the name The X-Files carries with it if we aren't careful, and the pilot episode of the series is not equipped to deal with that weight. It's by no means a bad introduction to the show. On the contrary, as I said, the formula is right there ready to go, all it takes is a short warm-up to get the scenario laid out. We have a no-nonsense FBI special agent, Dr. Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson), who has been selected thanks to her background in medical science to serve as the agency's spy in figuring out just what the hell is going on in the basement office of Special Agent Fox Mulder (David Duchovny), a brilliant profiler who has of late gotten himself obsessed with some FBI arcana called the X-files. These are cases deemed unsolvable for some reason; Mulder has decided to figure out the solutions, and is causing some amount of agita to the higher-ups, including in this case Division Chief Blevins (Charles Cioffi), and a sour-faced smoking man (William B. Davis) who gets a really pointed single that makes it clear that even when they didn't know that he'd be coming back, they knew that Davis had the kind of presence that's too good to ignore. Once Scully arrives in the cluttered office, with its walls full of various conspiracist newspaper headlines and a poster of a flying saucer boldly marked "I Want To Believe", Mulder immediately pegs her as a plant, but he's so eager to have somebody he can badger with his wild theories that he pretty quickly overlooks this, as he drags her along to Oregon, where a teenage girl was recently found dead in the woods - the fourth member of the same high school graduating class to die under strange, even inexplicable circumstances.

Judged by the standards of later X-Files episodes - even later in the same month - the pilot is remarkably simple and unambitious. It's never entirely clear why he has already decided, before we meet him, that it must be aliens (other than because, as we'll learn, he always thinks that it must be aliens), and much of the plotting that follows is to confirm that he's right. It's clear that Carter, in writing the script, hadn't fully decided how the two main characters were going to interact, and how we in the audience are meant to interact with them. We enter the story along with Scully, and we gain information as she does. This particularly means that we gain information about Mulder as she does: in a sense, he's the central mystery of the story. Certainly, he doesn't feel nearly as much like a protagonist in a classic sense as Scully does. We observe him more than we observe with him; it's never entirely clear what he already knows and is merely hoping to confirm, versus what he's actually learning as we learn it. The episode's most effective sequence, in which Mulder and Scully experience a time displacement event during a rainstorm, when they drive over a peculiar stretch of asphalt near the woods where the kids have been showing up dead, is a particularly clear example of this: it's presented within the episode as a strange and unnerving event (complete with little freeze frame and flash to white, a stylistic quirk that doesn't at all resemble anything the series would ever do again), and we're meant to experience it as Scully does, a confusing, even disturbing disruption. Mulder, meanwhile, is excited and energised. it's a great way to give us a visceral understanding of how these two different people are going to respond to the various incomprehensible phenomena the series plans to throw at them; but it also alienates us from Mulder somewhat.

Given how the script treats Mulder, it's not all that shocking that Duchovny hasn't figured the character out. In the 180-odd episodes of the show that he and Anderson appeared in together, I don't think there's a single time where I'd say that he was giving the better performance, but the gap between them is particularly pronounced in the pilot. To be fair, Anderson hasn't quite figured Scully out either, in large part because Carter is fairly overtly writing her as a generic version of Clarice Starling from The Silence of the Lambs. But Anderson at least has a clear understanding of how the character is going to function in an ongoing series, as a voice of measured reason, who strains but never cracks in trying to make sense of the bizarre things that she witnesses (she's entirely responsible for one of the episode's other best moments: near the end, Scully is silently contemplating a strange metal device she found in a corpse earlier in the episode, and Anderson makes sure to base this in Scully's curiosity as much as her confusion). Duchovny's performance is too caught up in the limitations of the writing, and he makes Mulder far more abrasive and smug than the character would quickly become. He makes the character almost gleefully snide and superior, something that makes sense in the context of this one story, but would quickly become untenable in a series lead who is meant to be one of our two entry points into these weird tales. Only one scene softens him, when Mulder shares a bit of backstory about his sister, who disappeared in a still-unsolved case; in the long term, this will become a defining part of the show's ongoing narrative, but in the short term, it helps to cut some of the cockiness and actually give Duchovny a subdued beat to play, his only one in the episode.

There are other little shortcomings littered throughout the episode. A coffin being exhumed falls and rolls along the ground, splitting to reveal an inexplicable, inhuman corpse; it's one of the moments where the episode is most clearly trying to tap into horror, and the corpse, at least, gets us there. But Mark Snow's score is far too eager to overstress how terrifying this is, well before it actually has become that way, and it makes the moment more campy than scary. At another point, Anderon strips down to her underwear in a moment that seems to have weirdly misidentified this as a much pulpier, tawdrier mode of sci-fi than anything else in the whole episode could possibly explain.

For all that, though, this mostly does a good job of setting out the rules for what The X-Files is going to become. The opening scene gets the mood going immediately, starting off in a gloomy nighttime forest that tells us right from the start what we should anticipate from the series' look: it will plunge us into dark, murky places where slivers of light reveal far too little for us to figure out what the hell is going on. And the scene that follows plays a storytelling trick that the show will get a lot of mileage out of, planting a mystery in a mystery: we see a young woman die of something unseen, but that's not the mystery: the mystery comes with the detective (Leon Russom) whose weary reaction to the dead body sets up the reveal that this is the fourth such corpse (incidentally, this scene, with the discovery of a dead girl, covered in flecks of dirt - at the very start of the new series, no less - is the most obvious lift from Twin Peaks that The X-Files will ever make).

This opening sets up the clearest strength of the pilot: it's long on atmosphere. Much of the episode takes place at night, in the woods, or in the rain; even some of the interiors are lit with just one or two hard, directional lights, to give those spaces a sense of gloominess even when we can see everything that's going on. The promise the pilot makes is that The X-Files will take us to shadowy places, full of unseen dangers, and even if the specifics of this particular plot are a bit too straightforward to feel like we've really begun plunging the unknown, the moodiness surrounding that plot makes it feel more foreboding and mysterious than it actually earns. It's not more than a solid pilot, but it does the most important thing for an episode in its position to do: it gives us a clear sense of what the really great version of this material might look like.

Grade: B