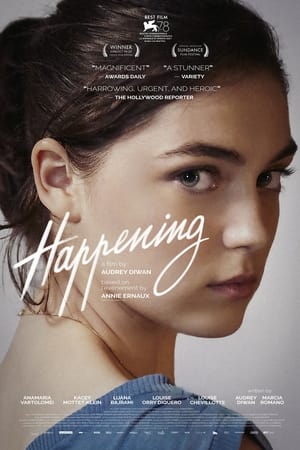

On March 16, 1979, Columbia Pictures released The China Syndrome, a cautionary tale (starring Jane Fonda, Michael Douglas and Jack Lemmon) about an accident at an American nuclear power plant. Twelve days later, the nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania experienced a partial meltdown—still the worst such accident we’ve had, over 40 years later, and probably still the most disturbing life-imitates-art coincidence on record, at least in terms of the timing. This week sees a dishearteningly strong challenger for the latter title, though, and you should know that I sat down to watch the 2021 Venice Film Festival Golden Lion winner roughly six hours after we all learned that the Supreme Court is poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. Under those circumstances, and with zero advance knowledge regarding the narrative (I try to go into acclaimed movies cold whenever possible), it was hard not to be emotionally blindsided by the film’s grueling portrait of a young woman desperately trying to have an abortion without either accidentally killing herself or winding up in jail. Adapted from a French memoir, its original title, L’Événement (The Event), alludes to a phrase about birth from which the word “happy” has pointedly been elided, but nobody could possibly have predicted the bitter resonance that would suddenly envelop its English-language title: Happening.

Not that director and co-screenwriter Audrey Diwan wasn’t already conscious of contemporary ramifications. Happening is set in 1963, but that’s not immediately apparent; Diwan, costume designer Isabelle Pannetier, production designer Diène Bérété and art director Omid Gharakhanian go out of their way to avoid any obvious period signifiers during the film’s opening stretch, even as everything looks more or less chronologically accurate. You register pretty quickly that nobody has a smartphone, but the specific era remains uncertain for a while, and that seems very much by design. France didn’t legalize abortion until 1975, and so Happening depicts a world in which having one is nearly impossible and insanely risky; while Diwan doesn’t go to the quasi-surreal extreme of Christian Petzold’s Transit (which tells a period story without attempting to hide modern cars and such), she clearly wanted to ensure that we can’t dismiss what happens as horrors from a less enlightened time that we’ve thankfully escaped. Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake (which likewise won the Golden Lion, in 2004) packs a wallop, but it’s possible to take comfort from all of the ways in which it’s blatantly taking place long, long ago (though only 13 years earlier than Happening). Not so here.

The previous film that Happening most resembles—to the point where a more churlish viewer, or maybe just someone who’s less upset by extremely current events, could question its necessity—is Romania’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, which failed to win the Golden Lion at Venice only because it had already won the Palme d’Or at Cannes four months earlier. (Abortion access has a truly stellar festival track record—see also Never Rarely Sometimes Always, which won Sundance’s dramatic competition two years ago.) Both even star an actor with the same first name: Anamaria Marinca played the pregnant woman in 4/3/2, while Happening sticks uncomfortably, Dardennes-style close to Anamaria Vartolomei as Anne Duchesne, a college student with an eye toward possibly teaching someday. Continuing her education while pregnant wasn’t an option at the time, so Anne doesn’t even entertain the thought of carrying the fetus to term. “I’d like a child one day,” she tells someone, “but not instead of a life.” Because anyone receiving, performing, assisting with, or otherwise enabling an abortion can be criminally charged, she’s forced to take a chance on the French equivalent of Vera Drake (played by Anna Mouglalis), though just finding her takes dangerously long; Diwan punctuates Happening with onscreen text, beginning with “3 weeks” and slowly progressing to “12 weeks.”

That’s one way in which this film distinguishes itself from Cristian Mungiu’s: 4/3/2 takes place during the course of a single incredibly harrowing day, whereas Happening maintains simmering tension over several months. More crucial, however, is the difference between Marinca’s Gabita, who’s supported throughout by best friend Otilia (again, see also Never Rarely Sometimes Always, which likewise foregrounds a close friendship), and Anne, who goes through her ordeal utterly alone. It’s not that Anne lacks for intimates, either. Early on, she’s constantly hanging with fellow students Hélène (Luàna Bajrami) and Brigitte (Louise Orry-Diquéro), though both seem unduly concerned by her apparent interest in a local firefighter (Cyril Metzger) who frequents their favorite bar. To a surprising extent, this is a film about women policing each other’s bodies: There’s a crew of mean girls who keep more or less calling Anne a slut, without even knowing that she’s pregnant—Diwan stages one of these scenes in the dorm shower, à la Carrie, calling attention to the female form while associating nudity with vulnerability rather than titillation—and at least two of the three amigos, Anne and Hélène, hide the fact that they’re sexually active even from each other, fearing that they’ll be harshly judged (which indeed Anne initially is, particularly by Brigitte). Nor does Anne feel comfortable going to her mother (Sandrine Bonnaire), evidently for fear that she’ll be forcibly yanked from school should Mom find out.

Happening’s most significant offhand moment occurs during one of Anne’s occasional visits home. She attends college in Angoulême—the city where Wes Anderson shot The French Dispatch, though you won’t be surprised to hear that this film looks exactly nothing like that one—but grew up in what looks like a much more rural area; her parents run a small café, and it’s either stated or strongly implied that Anne’s the first person in the family to achieve academic distinction of any kind. Anyway, a childhood friend who works at a factory examines Anne’s hands at one point and remarks upon how little evidence of work they evince, noting that she no longer recognizes her own. This isn’t said with any rancor, nor is it dwelt upon, but Diwan includes it for a reason. On the one (literal) hand, it acknowledges a certain degree of privilege; Anne eventually comes up with the 400 francs for her back-alley abortion by selling books and jewelry, which is more than many other women might manage. On the other (literal) hand, it emphasizes the fate that Anne seeks to avoid—having a baby now could easily land her in a factory job for the rest of her life, killing her dream of being a teacher (which later shifts to becoming a writer—Annie Ernoux, née Duchesne, who wrote the source memoir over 20 years ago, has long been one of France’s most celebrated authors).

Like all films in this grim mini-genre, Happening can be hard to sit through. Diwan doesn’t shy away from the nightmare that inevitably ensues when abortions don’t take place in a medically safe environment, and the squeamish are hereby warned—those scenes aren’t graphic, but neither are they brief or sanitized. What prevents the film from feeling like a miserabilist slog is Vartolomei’s quietly volatile performance, which somehow makes Anne startlingly proactive even in her helplessness. She’s the kind of person who’ll roll up her sleeves and do it herself if she possibly can, and her despair here arises from the simple fact that she can’t (though she tries anyway, with a hand mirror and a very long knitting needle; again, sensitive viewers should proceed with caution). Diwan’s screenplay, written with Marcia Romano, necessarily omits almost all of Ernaux’s thoughts about what she experienced (there’s no voiceover narration), and gives the onscreen Anne relatively little dialogue; Vartolomei has to convey a great deal via silent intensity and the occasional sharp outburst. “I won’t leave,” Anne tells one doctor who orders her out of his office, leaning forward and staring a fiery hole into his accordance with an unjust law. “Help me.” While she eventually finds someone who will, and obviously survived to write about it, it’s impossible to watch Happening and not think of the many American women who’ll soon be in a similar position and may have a less happy ending. It’s a movie that’s too familiar in its broad strokes to feel like a great work of art, but also too familiar not to inspire anger, frustration, and a deep, abiding sorrow.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.