Blockbuster History: Country houses

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. In the week now ending: Downton Abbey: A New Era is a movie with a script by Julian Fellowes, focused on the inner workings of an English country house, not least on the fraught interrelationship between the rich folk upstairs and the staff downstairs, and Maggie Smith is in the cast? Sometimes the choice really does get made for me.

The career of the great Robert Altman as a major American director breaks, I would say, into four phases, almost perfectly corresponding with the decades in which he worked. In 1970, M*A*S*H transformed him on the spot from TV workhorse with a couple of features under his belt into one of the leading lights of the bold new face of Hollywood, and he spent that whole decade churning out world-class masterpieces at an outrageous clip. In 1990, Popeye exploded in his face and dropped him Director Jail for ten years of weird, itchy features and TV movies made with almost no institutional backing to speak of. In 1990, Vincent & Theo won back the critics and then 1992's The Player fully brought him back into the good graces of the film industry. The '90s were a strange decade for the filmmaker, though, in that he kept getting huge all-star casts to produce odd little minor works that hardly anybody loves; other than The Player and its immediate follow-up Short Cuts, all of his films from that era were met with a kind of uncertain, dubious "oh, well... that's what you're doing now, huh" sort of critical notice, and extremely muted box office. This culminated in 2000's Dr. T & the Women, a big Indiewood film with Richard Gere in the lead that received some of the most disappointed reviews of Altman's career and continued a trend of box office underperformance.

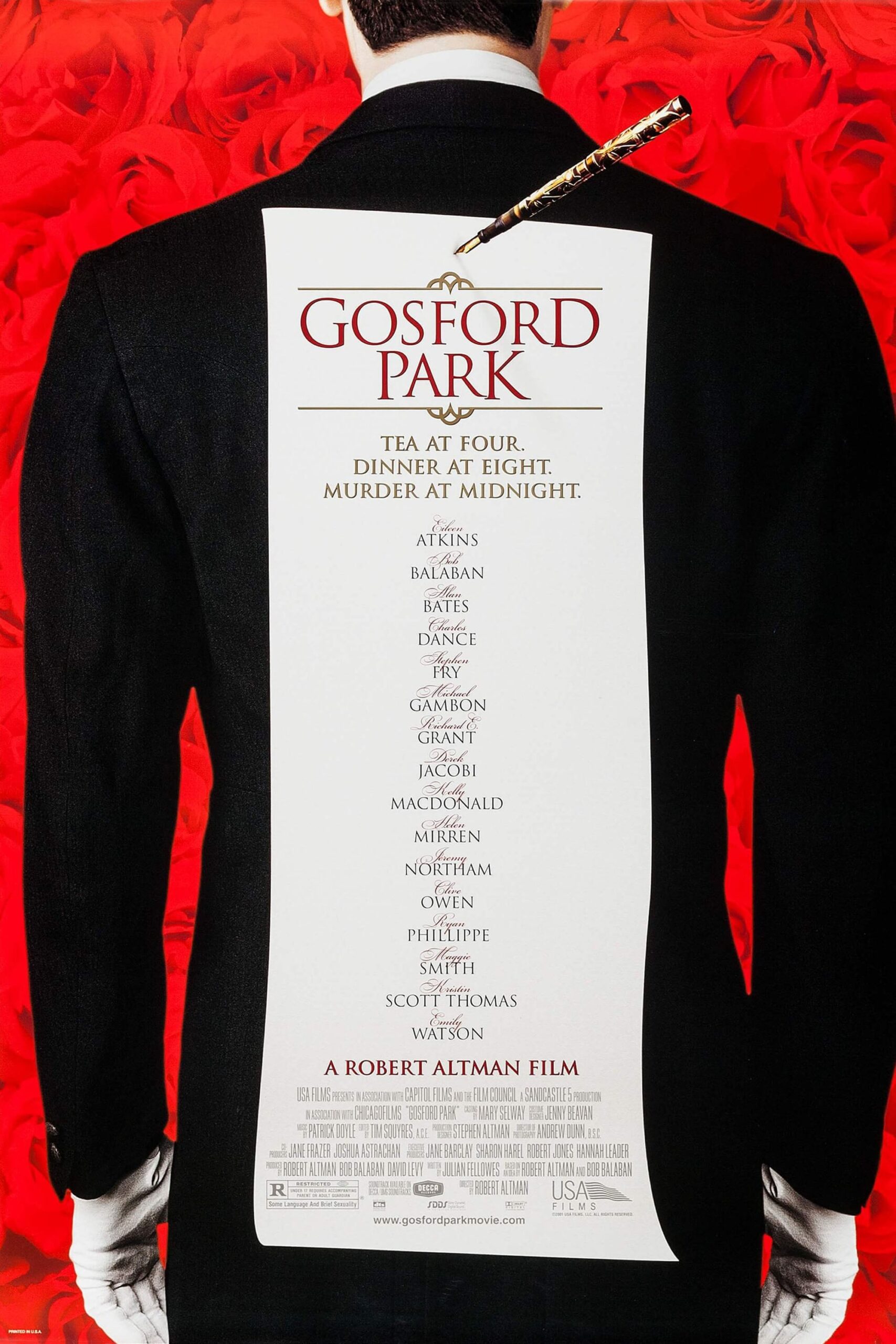

His next film, accordingly found him having to do something that, I believe, he had not been obliged to do since that selfsame Vincent & Theo: he had to leave the United States to get it funded. Formally speaking, 2001's Gosford Park is a UK/US/Italian co-production, but let's not bury things below a lot of transnational gobbledygook: it's an English movie. It's set in a English country house, it's about specifically English class structures, its primary point of reference is Agatha Christie. And humming under that Englishness, Altman directs it exactly like an Altman film, bringing a sharp, caustic American attitude to bear that never noses its way to the forefront, but always makes this feel like so much more than the BBC One costume drama primness that its surface level trappings would imply (to say nothing of the subsequent career of first-time screenwriter Julian Fellowes, whose later work is wildly out of step with the lacerating intelligence of Gosford Park. But Altman films where the screenplay is more of a scaffolding than an actual approximation of the final project certainly wasn't a new thing in 2001).

The film was a major hit, the second highest-grossing film of Altman's career after M*A*S*H, and recipient of the most Academy Award nominations (seven, including Best Picture and Best Director). And so a mere nine years after the last "welcome back to Hollywood, we love you!" movie, Altman got another one, inaugurating the last phase of his career, the Elder Statesman years. Which, one suspects, would probably not have lasted, given that his very next film was 2003's plotless ballet-driven art film The Company. But he died in 2007, after completing only one further feature, 2006's A Prairie Home Companion, and 2004 TV miniseries, Tanner on Tanner, and so we get to say and feel good about it: Altman got back into everybody's good graces and ended his career that way, the end.

That's a much more sentimental mood to approach Gosford Park than the film earns. This is a brusque movie with a sharp sardonic streak, not exactly a "comedy", even a dark one, but suffused with a tart, ironic wit. It follows directly in the tradition of Jean Renoir's 1939 masterpiece The Rules of the Game by using a country home over the course of a shooting weekend to examine how the upper class guests of the house and the lower class servants - upstairs and downstairs, encoded right into the physical structure - as closed environment from which to diagnose all the ills of a social order. I'm certainly not saying Gosford Park is doing this every bit as well as The Rules of the Game, and indeed it mostly like can't: the French film was made about a society that was still in existence all around it (and rapidly dying, as 1939 brought war to Europe), while Gosford Park is largely an exercise in grumpy nostalgia. One can certainly go too far in crediting Altman, Fellowes, and Bob Balaban (who apparently came up with the basic idea of "we should do a movie about X, set in Y", and shares a credit to that effect with Altman) with an excess of satiric edge; Gosford Park is poking fun at snobby English classism, not wrathfully holding its hypocrisies up to the light and declaring it should all be brought down. But it does poke fun rather acerbically. As would almost invariably have to be the case for a film by the director of M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, really a whole hell of a lot of things, Gosford Park has an unabashed populist attitude, a conviction that at any rate, the people doing all of the work are clearly going to be better company and offer more insights than the preening gasbags upstairs.

At which point it would benefit the review to have some of those workers and some of those gasbags laid out, and explain the plot, insofar as there is one. It's a hunting weekend at Gosford Park, the country home of Sir William McCordle (Michael Gambon), an industrialist; most of the guests are relatives of his wife Lady Sylvia (Kristin Scott Thomas), including her younger sister Louisa (Geraldine Summerville), Lady Stockbridge, and her husband Lord Stockbridge (Charles Dance); their youngest sister Lavinia Meredith (Natasha Wightman) and her husband, the terribly broke Anthony Meredith (Tom Hollander); and the sisters' imperious aunt, the Dowager Countess of Trentham (Maggie Smith). We start the film at the Countess's estate, as she gets in the car in the pouring rain, and are so introduced immediately to the basic visual strategy that Altman, cinematographer Andrew Dunn, and editor Tim Squyres will be using over the film's well-paced and pleasantly overstuffed 137 minutes: we always see the upper class folks from a slight distance, one that makes things feel somewhat objective and observational, whereas we generally see the lower class people from angles that tie us subjectively to their perspective, making it feel like we're watching the film with and through them. This being a Robert Altman ensemble piece with 44 named characters of whom 29 count as "major", we're obviously not going to be watching the film through every lower-class character's perspective, but it's certainly noticeable even in the crowd shots: when we're watching a crowd of the downstairs workers crammed into their spaces, it always feels like there are specific people whose understanding of the moment comes to the fore; in the crowded dining rooms and drawing rooms upstairs, we generally don't, feeling more like we're on the edge of the space, watching. In other words, we're psychologically and emotionally invested in the staff through the way scenes are constructed, and we're not invested in their masters. Again, populism.

As for that construction: most of Gosford Park was shot with two simultaneous cameras that were moving, not "at random", but without a clear plan laid out in advance, meaning that Altman worked with the actors to set up how they'd inhabit spaces but not how they were to act onscreen. The result, we are told, is that the cast members mostly never knew when they could be safely out of character, and so they just stayed in that mental space throughout the whole of scenes. The effect is tangible, and galvanising: I genuinely think there's a level of "we are watching real-life scenes that are happening because the lives of the characters would necessarily make them happen, not because they fit into the film's narrative, and actually, what is the film's 'narrative', anyway?" here that I don't get so strongly from any other Altman film but Nashville. When we're watching actions in a crowd, there's nothing telling us what characters "matter", and even when the most famous faces in the movie are present onscreen, it's often not the case that they feel like they're drawing more attention that people who I've never seen in anything else.

But back to the opening scene: we're watching the Countess as a remote figure, and I don't even know that we really see her face at this point, but we do get our first good look at Mary Maceachran (Kelly Macdonald), the newly-hired lady's maid to the countess, and the closest thing we get to a main character; we meet her first, we say goodbye to her last, and her inexperience with the world of country houses means that a lot of the other characters will explain rules to her in front of us, so we can figure out what the hell is happening. Other figures of note: Mrs Wilson (Helen Mirren), the housekeeper at Gosford; Mr Jennings (Alan Bates), the butler; Elsie (Emily Watson), the head housemaid; Probert (Derek Jacobi), Sir William's valet; Mrs Croft (Eileen Atkins), the cook.

I'm basically just grabbing a few names for form's sake: again, we have 29 main characters. But I think that's more than enough to make it clear that Gosford Park has a stunningly packed cast; on paper, it might be the greatest concentration of heavy-hitting talent of any English-language film released in the 21st Century. And under Altman's immaculate guiding hand, they are literally all doing tremendous work, with several of those heavy hitters giving what I might be really tempted to the best screening acting of their careers. The closest thing there is to a weak link is Ryan Phillippe, a late substitution for Jude Law, and even in his case it barely counts, since the very worst part of his performance (a bad Scottish accent so far off the mark that I thought it was a bad Irish accent) turns out to have a narrative function. Part of what makes the acting so especially impressive is how carefully tamped down it is. There are a lot of people here I associate with a tendency to go big and showy, chewing scenery wherever they can find it: Smith, Gambon, Richard E. Grant. Every last one of them has been guided towards the shaggy naturalism that the loosely-structured scenes of people milling around doing what they do every day demands - even Smith, giving by far the most grounded and human performance I have ever seen from her, despite how well the role apparently fits in with the imperious theatrical she tends to bring to her tart-tongued grande dames.

I love this Nashville-esque phase of the movie intently: this meandering tour of the nuts-and-bolts mechanics of how country houses work, the hierarchies within both of the two major domains, and the way people can or cannot navigate those hierarchies comfortably. That manifests in a lot of ways, both upstairs and downstairs: the film implicitly contrasts Mary with Robert Parks (Clive Owen), also recently hired, showing how different their confidence levels are as they move through the hallways and service corridors, and giving Macdonald and Owen ample opportunity to show off a whole lot of acting skills that make them the film's standouts (this was early enough in both of their careers that the film has a certain quality of showing off these interesting new discoveries). The visiting Hollywood filmmaker Morris Weissman (Balaban) humiliates himself in the second half by having loud phone conversations at inopportune moments, but being American, he doesn't realise he's humiliated and wouldn't care if he was. In one of the film's two Oscar-nominated performances (Maggie Smith gave the other), Mirren is the most effortlessly mechanical and precise member of the staff, so perfectly attuned to the rhythms of scenes and the blocking of the whole cast that she barely ever seems to register as a character rather than a presence, right up until, almost at the end of the film, she gets a big monologue declaring basically the same thing I just said (the best-acted part of the whole movie, in my opinion), and then almost immediately after, a big sloppy emotional scene that feels so much more affecting because of the tight control she literally just demonstrated in the explosive "perfect servant".

"How does a country home work?" is fascinating as a story, presented with such care in the invisible but omnipresent control of POV, miked to facilitate some outstanding sound mixing that's less bravura than the great Altman films of the '70s, but in part that's because it's taking place in such a less messy environment. It is so impressive, in fact, that I'm sort of let down by the film's turn to genre: a little past the midway point, somebody is killed, and this becomes an Agatha Christie parody, of sorts. The whole movie pivots around it; Stephen Fry shows up to play the inspector, giving every inch a "Stephen Fry performance" (his facial expressions as he does some business with a pipe in one of his first scenes are superbly hammy), making such a huge break from the rest of the acting that it's hard not to notice that we're in a brand new part of the film. It's all very well done, and I do love how emphatically sarcastic it gets: every single character save maybe one is happier with the victim dead, and it's one of the nastier jabs at the self-importance of the landed gentry the film makes. And it's also quite interesting how the film manages our knowledge at this point: there's a tension between its sprawling "we see everything as the camera wanders around" vibe and the fact that we don't know whodunnit, and this tension is magnified by how we still seem to be moving around and seeing everything.

It has the happy benefit of making the film's murder mystery sequence more about the rearrangement of character relationships than simply lining everybody up, Christie-style, to question them and announce a solution. In fact, the murder doesn't even interrupt the several other subplots that have grown out of the film, just redirects them, and the way that we keep getting slice of conversation in passing to explain the state of those subplots doesn't change. Nor does the main thematic focus: the only way to solve the mystery is by occupying the perspective of the staff, which is why nobody upstairs ever has a clue what happened, nor do they care. And it's a little on-the-nose in clarifying that (Fry has an excellent delivery of a line that's almost insultingly obvious, and so manages to mostly safe it), but it's one of the few times that Gosford Park is anything less than subtle, even graceful in its manipulation of tones, themes, and the audience ourselves.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

The career of the great Robert Altman as a major American director breaks, I would say, into four phases, almost perfectly corresponding with the decades in which he worked. In 1970, M*A*S*H transformed him on the spot from TV workhorse with a couple of features under his belt into one of the leading lights of the bold new face of Hollywood, and he spent that whole decade churning out world-class masterpieces at an outrageous clip. In 1990, Popeye exploded in his face and dropped him Director Jail for ten years of weird, itchy features and TV movies made with almost no institutional backing to speak of. In 1990, Vincent & Theo won back the critics and then 1992's The Player fully brought him back into the good graces of the film industry. The '90s were a strange decade for the filmmaker, though, in that he kept getting huge all-star casts to produce odd little minor works that hardly anybody loves; other than The Player and its immediate follow-up Short Cuts, all of his films from that era were met with a kind of uncertain, dubious "oh, well... that's what you're doing now, huh" sort of critical notice, and extremely muted box office. This culminated in 2000's Dr. T & the Women, a big Indiewood film with Richard Gere in the lead that received some of the most disappointed reviews of Altman's career and continued a trend of box office underperformance.

His next film, accordingly found him having to do something that, I believe, he had not been obliged to do since that selfsame Vincent & Theo: he had to leave the United States to get it funded. Formally speaking, 2001's Gosford Park is a UK/US/Italian co-production, but let's not bury things below a lot of transnational gobbledygook: it's an English movie. It's set in a English country house, it's about specifically English class structures, its primary point of reference is Agatha Christie. And humming under that Englishness, Altman directs it exactly like an Altman film, bringing a sharp, caustic American attitude to bear that never noses its way to the forefront, but always makes this feel like so much more than the BBC One costume drama primness that its surface level trappings would imply (to say nothing of the subsequent career of first-time screenwriter Julian Fellowes, whose later work is wildly out of step with the lacerating intelligence of Gosford Park. But Altman films where the screenplay is more of a scaffolding than an actual approximation of the final project certainly wasn't a new thing in 2001).

The film was a major hit, the second highest-grossing film of Altman's career after M*A*S*H, and recipient of the most Academy Award nominations (seven, including Best Picture and Best Director). And so a mere nine years after the last "welcome back to Hollywood, we love you!" movie, Altman got another one, inaugurating the last phase of his career, the Elder Statesman years. Which, one suspects, would probably not have lasted, given that his very next film was 2003's plotless ballet-driven art film The Company. But he died in 2007, after completing only one further feature, 2006's A Prairie Home Companion, and 2004 TV miniseries, Tanner on Tanner, and so we get to say and feel good about it: Altman got back into everybody's good graces and ended his career that way, the end.

That's a much more sentimental mood to approach Gosford Park than the film earns. This is a brusque movie with a sharp sardonic streak, not exactly a "comedy", even a dark one, but suffused with a tart, ironic wit. It follows directly in the tradition of Jean Renoir's 1939 masterpiece The Rules of the Game by using a country home over the course of a shooting weekend to examine how the upper class guests of the house and the lower class servants - upstairs and downstairs, encoded right into the physical structure - as closed environment from which to diagnose all the ills of a social order. I'm certainly not saying Gosford Park is doing this every bit as well as The Rules of the Game, and indeed it mostly like can't: the French film was made about a society that was still in existence all around it (and rapidly dying, as 1939 brought war to Europe), while Gosford Park is largely an exercise in grumpy nostalgia. One can certainly go too far in crediting Altman, Fellowes, and Bob Balaban (who apparently came up with the basic idea of "we should do a movie about X, set in Y", and shares a credit to that effect with Altman) with an excess of satiric edge; Gosford Park is poking fun at snobby English classism, not wrathfully holding its hypocrisies up to the light and declaring it should all be brought down. But it does poke fun rather acerbically. As would almost invariably have to be the case for a film by the director of M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, really a whole hell of a lot of things, Gosford Park has an unabashed populist attitude, a conviction that at any rate, the people doing all of the work are clearly going to be better company and offer more insights than the preening gasbags upstairs.

At which point it would benefit the review to have some of those workers and some of those gasbags laid out, and explain the plot, insofar as there is one. It's a hunting weekend at Gosford Park, the country home of Sir William McCordle (Michael Gambon), an industrialist; most of the guests are relatives of his wife Lady Sylvia (Kristin Scott Thomas), including her younger sister Louisa (Geraldine Summerville), Lady Stockbridge, and her husband Lord Stockbridge (Charles Dance); their youngest sister Lavinia Meredith (Natasha Wightman) and her husband, the terribly broke Anthony Meredith (Tom Hollander); and the sisters' imperious aunt, the Dowager Countess of Trentham (Maggie Smith). We start the film at the Countess's estate, as she gets in the car in the pouring rain, and are so introduced immediately to the basic visual strategy that Altman, cinematographer Andrew Dunn, and editor Tim Squyres will be using over the film's well-paced and pleasantly overstuffed 137 minutes: we always see the upper class folks from a slight distance, one that makes things feel somewhat objective and observational, whereas we generally see the lower class people from angles that tie us subjectively to their perspective, making it feel like we're watching the film with and through them. This being a Robert Altman ensemble piece with 44 named characters of whom 29 count as "major", we're obviously not going to be watching the film through every lower-class character's perspective, but it's certainly noticeable even in the crowd shots: when we're watching a crowd of the downstairs workers crammed into their spaces, it always feels like there are specific people whose understanding of the moment comes to the fore; in the crowded dining rooms and drawing rooms upstairs, we generally don't, feeling more like we're on the edge of the space, watching. In other words, we're psychologically and emotionally invested in the staff through the way scenes are constructed, and we're not invested in their masters. Again, populism.

As for that construction: most of Gosford Park was shot with two simultaneous cameras that were moving, not "at random", but without a clear plan laid out in advance, meaning that Altman worked with the actors to set up how they'd inhabit spaces but not how they were to act onscreen. The result, we are told, is that the cast members mostly never knew when they could be safely out of character, and so they just stayed in that mental space throughout the whole of scenes. The effect is tangible, and galvanising: I genuinely think there's a level of "we are watching real-life scenes that are happening because the lives of the characters would necessarily make them happen, not because they fit into the film's narrative, and actually, what is the film's 'narrative', anyway?" here that I don't get so strongly from any other Altman film but Nashville. When we're watching actions in a crowd, there's nothing telling us what characters "matter", and even when the most famous faces in the movie are present onscreen, it's often not the case that they feel like they're drawing more attention that people who I've never seen in anything else.

But back to the opening scene: we're watching the Countess as a remote figure, and I don't even know that we really see her face at this point, but we do get our first good look at Mary Maceachran (Kelly Macdonald), the newly-hired lady's maid to the countess, and the closest thing we get to a main character; we meet her first, we say goodbye to her last, and her inexperience with the world of country houses means that a lot of the other characters will explain rules to her in front of us, so we can figure out what the hell is happening. Other figures of note: Mrs Wilson (Helen Mirren), the housekeeper at Gosford; Mr Jennings (Alan Bates), the butler; Elsie (Emily Watson), the head housemaid; Probert (Derek Jacobi), Sir William's valet; Mrs Croft (Eileen Atkins), the cook.

I'm basically just grabbing a few names for form's sake: again, we have 29 main characters. But I think that's more than enough to make it clear that Gosford Park has a stunningly packed cast; on paper, it might be the greatest concentration of heavy-hitting talent of any English-language film released in the 21st Century. And under Altman's immaculate guiding hand, they are literally all doing tremendous work, with several of those heavy hitters giving what I might be really tempted to the best screening acting of their careers. The closest thing there is to a weak link is Ryan Phillippe, a late substitution for Jude Law, and even in his case it barely counts, since the very worst part of his performance (a bad Scottish accent so far off the mark that I thought it was a bad Irish accent) turns out to have a narrative function. Part of what makes the acting so especially impressive is how carefully tamped down it is. There are a lot of people here I associate with a tendency to go big and showy, chewing scenery wherever they can find it: Smith, Gambon, Richard E. Grant. Every last one of them has been guided towards the shaggy naturalism that the loosely-structured scenes of people milling around doing what they do every day demands - even Smith, giving by far the most grounded and human performance I have ever seen from her, despite how well the role apparently fits in with the imperious theatrical she tends to bring to her tart-tongued grande dames.

I love this Nashville-esque phase of the movie intently: this meandering tour of the nuts-and-bolts mechanics of how country houses work, the hierarchies within both of the two major domains, and the way people can or cannot navigate those hierarchies comfortably. That manifests in a lot of ways, both upstairs and downstairs: the film implicitly contrasts Mary with Robert Parks (Clive Owen), also recently hired, showing how different their confidence levels are as they move through the hallways and service corridors, and giving Macdonald and Owen ample opportunity to show off a whole lot of acting skills that make them the film's standouts (this was early enough in both of their careers that the film has a certain quality of showing off these interesting new discoveries). The visiting Hollywood filmmaker Morris Weissman (Balaban) humiliates himself in the second half by having loud phone conversations at inopportune moments, but being American, he doesn't realise he's humiliated and wouldn't care if he was. In one of the film's two Oscar-nominated performances (Maggie Smith gave the other), Mirren is the most effortlessly mechanical and precise member of the staff, so perfectly attuned to the rhythms of scenes and the blocking of the whole cast that she barely ever seems to register as a character rather than a presence, right up until, almost at the end of the film, she gets a big monologue declaring basically the same thing I just said (the best-acted part of the whole movie, in my opinion), and then almost immediately after, a big sloppy emotional scene that feels so much more affecting because of the tight control she literally just demonstrated in the explosive "perfect servant".

"How does a country home work?" is fascinating as a story, presented with such care in the invisible but omnipresent control of POV, miked to facilitate some outstanding sound mixing that's less bravura than the great Altman films of the '70s, but in part that's because it's taking place in such a less messy environment. It is so impressive, in fact, that I'm sort of let down by the film's turn to genre: a little past the midway point, somebody is killed, and this becomes an Agatha Christie parody, of sorts. The whole movie pivots around it; Stephen Fry shows up to play the inspector, giving every inch a "Stephen Fry performance" (his facial expressions as he does some business with a pipe in one of his first scenes are superbly hammy), making such a huge break from the rest of the acting that it's hard not to notice that we're in a brand new part of the film. It's all very well done, and I do love how emphatically sarcastic it gets: every single character save maybe one is happier with the victim dead, and it's one of the nastier jabs at the self-importance of the landed gentry the film makes. And it's also quite interesting how the film manages our knowledge at this point: there's a tension between its sprawling "we see everything as the camera wanders around" vibe and the fact that we don't know whodunnit, and this tension is magnified by how we still seem to be moving around and seeing everything.

It has the happy benefit of making the film's murder mystery sequence more about the rearrangement of character relationships than simply lining everybody up, Christie-style, to question them and announce a solution. In fact, the murder doesn't even interrupt the several other subplots that have grown out of the film, just redirects them, and the way that we keep getting slice of conversation in passing to explain the state of those subplots doesn't change. Nor does the main thematic focus: the only way to solve the mystery is by occupying the perspective of the staff, which is why nobody upstairs ever has a clue what happened, nor do they care. And it's a little on-the-nose in clarifying that (Fry has an excellent delivery of a line that's almost insultingly obvious, and so manages to mostly safe it), but it's one of the few times that Gosford Park is anything less than subtle, even graceful in its manipulation of tones, themes, and the audience ourselves.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!