Last call for sin

A review requested by Morgan, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

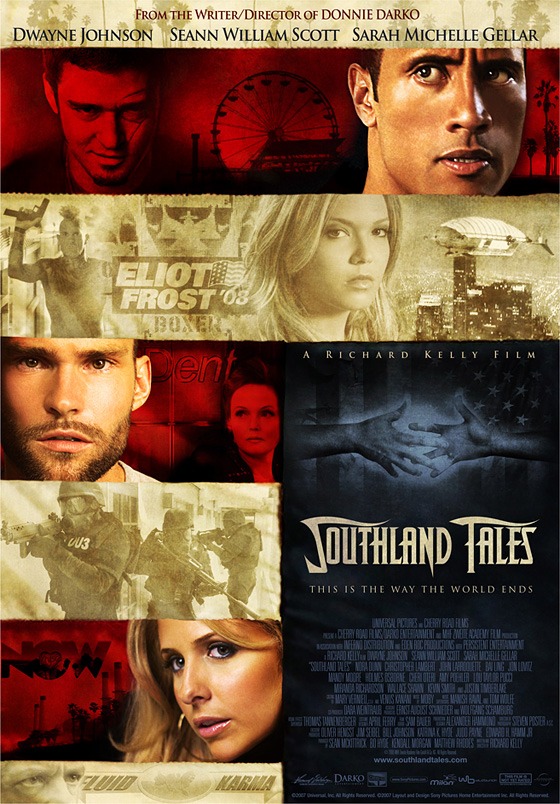

To call Southland Tales a messy film would be like calling the Battle of Stalingrad a little scuffle, or the sinking of RMS Titanic an unfortunate yachting incident. It is one of the towering achievements of Messy Cinema. Director Richard Kelly's second feature, and the one with which he burned through literally all of the goodwill and studio indulgence he earned in making 2001's instant cult classic Donnie Darko, was here indulging himself at a level that we almost never see indulged, with the brash hunger of somebody who had achieved pretty much all the success any wannabe filmmaker dreams of achieving when he was all of 26 years old. This includes, among other things, positioning the film as the second half of a narrative that was begun in a series of three graphic novels, written during production and in the long months between the film's premiere and its wide release

It is a movie that does not feel like the word "no" was ever said in the course of its production, even when the filmmaker was perhaps deliberately trying to court that response. As he sort of was, according to his own version of the story, when he submitted the incomplete film to the Cannes International Film Festival for its 2006 edition, only to be shocked when the festival accepted it. And so a rushed and unfinished version of the film screened to one of the most hostile audiences in the history of that famously prickly and heckling-prone festival. Over a year later, a shorter cut with substantially different visual effects was released to theaters, where it met with bad reviews, total audience disinterest, and that was pretty much it for Richard Kelly; he had enough gas in the tank to make The Box in 2009, which met with ever so vaguely less hostile reviews, considerably more box office attention (but still not enough to make it profitable), and that is effectively where his career ends. Though he has popped up from time to time to announce projects that don't go anywhere.

I have two things to say about Southland Tales regarding its predominant role in immediately sending one of the hottest indie whiz kids of the early 2000s straight to a lifetime sentence in Director Jail. First, any studio executive who wanted to give this man more money in the wake of how he set $17 million on fire here would be a lunatic who should instantly be fired. Second: goddamn, what a way to go. This is the right way to murder a promising career, alright: with the kind of genuinely visionary work that feels beholden only the The Art Itself, a radical, swirling hallucination of ideas that all feel grabbed at random, but which cumulatively all seem to building to some kind of internally consistent declaration of how life and the universe works, centered around a passionately-felt theme. I admittedly don't entirely know what the declaration is saying or what the theme is; "man, I really hate that George W. Bush guy" is certainly part of it, and hey, I agree, he was a real nogoodnik. But it takes more to make a tight film than really hating that George W. Bush guy.

But how damn dare I tell Southland Tales its business. The exact thing that makes this such a vital treasure of a film is that it refuses to do any of the things that movies do, unless it stumbles into them by accident. Sometimes this means that the film gets trapped in long stretches of ideas that don't work or can't communicate themselves or feel just puerile, in the smug way of a smart kid who thinks he is much smarter still, and has a pretty crude and underdeveloped sense of humor that he thinks makes him a master satirist, on top of everything. I am sure, though, more sure than any other time that I have ever made this claim, that this is the price we have to pay for the places where the film is brilliant. Or, if not brilliant, so shockingly weird and bold and genuinely willing to risk absolute madness to find a new way of doing things that it at least makes this feel like a genuine one-off, in Kelly's career and in pretty much all of cinema.

The two cuts of Southland Tales - the Cannes cut was 159 minutes, the theatrical cut is 144 minutes, for the record, and both are readily available these days - present effectively identical stories with distinctly different moods, and since the mood of the film is considerably more important to the experience of watching it, we will need to talk about both to some extent. But in the interests of having a baseline to talk about, I suppose I should first approach the narrative, doing so with no small amount of appropriate wariness. "This is an epic Los Angeles crime saga", as we are told by Boxer Santaros (Dwayne Johnson, appearing for the first time without "The Rock" attached to his name), an amnesiac action film star and son-in-law of the Republican vice presidential candidate in the 2008 election. And he's only talking about the screenplay he's written with porn star turned aspiring cultural commentator Krysta Now (Sarah Michelle Gellar), but since that script turns out to be somehow prophetic in describing the events of the Southland Tales universe itself, we can borrow his terminology to describe this pre- and inter-apocalyptic story of Los Angeles in the brink of an abyss (the film makes a direct comparison between itself and the similarly doom-laden 1950s thriller Kiss Me Deadly, a film noir that's secretly about the inevitability of nuclear destruction). Boxer is being used as a pawn in at least two directions: Krysta has associations with a neo-Marxist radical group whose members include Krysta's porn director Cyndi Pinziki (Nora Dunn), avant garde poets Dream (Amy Poehler) and Dion (Wood Harris), and short-tempered fixer Zora Carmichaels (Cheri Oteri). And Boxer's mother-in-law Nana Mae Frost (Miranda Richardson) is head of the same government surveillance department that the neo-Marxists are hoping to destroy. There's another faction to consider: a team of visionary energy scientists led by Baron von Westphalen (Wallace Shawn), who shares a name and possibly a line of descent with Karl Marx's wife Jenny von Westphalen; other than "no good", it's tough to say what von Westphalen is up to with his posse of characters who are grotesque even by the standards this film sets for itself (the ones we need to worry about most are played by Bai Ling, Zelda Rubinstein, and Beth Grant; Kevin Smith eventually shows up, caked in latex and a giant grey beard, and this bit of stunt casting pushes Southland Tales fully into dream-logic derangement at the exact moment it needs that push). Floating around in all of this are identical twin brothers, Ronald and Roland Taverner (Sean William Scott), one an emotionally damaged ex-soldier, one a cop, both plagued by an inability to keep their identities straight, and a general feeling of being pressed upon by something much more cosmically troubling than the rise of anti-U.S. terrorist attacks and the expansion of the U.S. security state that most of the other characters are worried about. Because this is a Richard Kelly script, and he would never see fit to write a simple little political satire with like five different levels of cons, obfuscation, double-crossing, and disinformation without making sure the whole thing is a mindfuck about the nature of physical reality with a good dose of barely-comprehensible quantum mechanics underpinning the whole thing.

First things first: Southland Tales isn't a very smart political satire, though I do not know if it's fair to say that it's claiming otherwise. The film takes great joy in its crass humor, after all. Also, at the very broadest remove, the film's message is that the Right is evil, the Left is useless, and it won't matter soon since we'll all be dead in a (possibly nuclear) ecological catastrophe. Which may indeed be correct, but it's not smart satire. Anyway, the film knows, very clearly, that life in the United States under the Bush administration was sending everything to hell at top speed, and that has an awful lot to do with the extraordinary (and as we have since learned, irreversible*) erosion of privacy carried out through the passage of the PATRIOT Act. But look for a well-argued theory of political philosophy, and you will not find it.

Which I would say is both fine and, indeed, appropriate - Southland Tales is a movie, not an essay, and movies live in the realm of impression, emotion, sensation. And what this film is fantastic at, is capturing the feeling of a society in its death throes, where even the power brokers with an iron grip on the levers of government and industry are barely hanging together. Even the frequent incoherence of the narrative plays into this as a positive element, not just an error by a second-time director who got in over his head. Though it very well could have been such an error - not that it matters! The sheer chaos of the movie is the point, however Kelly got to it. But it goes beyond the script: every single thing about the film's construction, visually and dramatically, feeds into the overwhelming sense of a world that has broken past the point of repair. It's overstuffed with extraneous crap in the production design and art direction, some of which seems like it's trying to force some kind of symbolic meaning on the world, but never seems to actually create any sort of reliable pattern, just a series of erratic references to other things in this movie, and to things outside of it. The acting is fully of weirdly mannered performances, in which nearly every single actor was cast specifically because Kelly wanted them to things they had never established themselves capable of, and it's a crapshoot who actually succeeds in finding something to hold onto. Johnson, I would say, is a clear-cut winner here; it was his first chance to play things silly, and he thrived with things like the way he nervously flutters his fingers in what I can't help but read as an Oliver Hardy homage. It would be extremely hard to say anyone was doing their "best" work in this film, which has so little of what can be called straightforward character material, but it is my "favorite" of Johnson's movie performances. But anyway, part of the pleasure of the thing is that everybody is attack the script in their own way, with everything from Oteri's over-the-top yelling to Richardson sinking into stillness and a loose Texan drawl to Shawn having a great time going fully into camp as a way of coping with his utter bafflement as to the script's meaning. And these all feel like equally valid ways of trying to find some anchor in the middle of events they can by no means control.

The editing of the two cuts of Southland Tales functions a bit differently in this regard, such that I can't really call one of them "better". There's only one significant narrative change: a scene of von Westphalen gleefully betraying a Japanese business partner more or less opened the original cut, giving us an immediate sense of his viciousness and the overall level of apocalyptic lawlessness and violence that rules this world; the theatrical cut moves it back by over an hour. Otherwise, the difference is in textures and atmosphere. For one thing, the theatrical cut is less overtly comic: Janeane Garofalo's performance, the most conventionally funny part of the original cut, has been reduced to little more than a glancing cameo in the shorter version. And there are smaller places where a different choice of take, or cutting out individual lines, softens the impact of the more overt gags. The theatrical cut loses some of the connective tissue, giving a more fragmentary feeling to the narrative: it is a bit more blunt about what's going on, with several lines of voiceover narrative added to clearly indicate things that were a bit vague originally. It's sharper, not in the sense of being precise, but in the sense that it feels like you could cut yourself on it.

The Cannes cut, in contrast, is dreamier and more diffuse: almost exclusively in the opening, but part of the way movies work is by giving us first impressions that color our entire experience. The presentation of the backstory is more like a fable, more ambiguous; an opening montage of home video footage showing a nuclear bomb strike Abilene, Texas on 4 July, 2005 goes on much longer in the Cannes cut before the bombs go off, and the footage is window-boxed within the 2.35:1 frame, making it a little distant from us. Even the appearance of the word "Abilene" onscreen is vaguer in the Cannes cut: it both points at the town where this took place, but also serves to introduce our narrator, Pilot Abilene (Justin Timberlake). This double-meaning is lost in the theatrical cut. And Abilene's narration is itself different: Kelly had Timberlake re-record all of it to pin down a different mood for the theatrical cut, something more normal. In the Cannes cut, Timberlake's tone of voice is lilting and dreamy, almost feminine in its cadences, and it instantly creates a much hazier vibe than anything in the theatrical cut ever achieves, or tries for. Meanwhile, while the longer cut explains less, it shows more, and the slower development of the film's first third, especially, makes it a little easier to place ourselves physically in the movie, if not narratively.

Either way, the end result is similar enough: a world gone mad needs a film to go mad with it. This is most overwhelming in the end, when Kelly goes all-in on visionary sci-fi madness, but it's also there right from the start, in the visually noisy news report that the film throws at us with no sign of how we're meant to read it, or figure out what is exposition, what is world-building, and what's just extraneous.

The best sign of the overall approach Southland Tales takes, I think, is that the scene where it most feels like it "clicks", and the scene that Kelly apparently regarded as the heart of the entire project, is at best a narratively inconsequential drug hallucination, and might very well take place entirely outside of the film's diegesis altogether: shortly after the film's midway point, Pilot Abilene finally enters the movie in the flesh in a significant way, to shoot himself up with some sci-fi drug, and thence to star in a music video for about half of the Killers song "All These Things That I've Done". The camera glides along, leading Timberlake as he stares uncomfortably into the lens, looking surly and sleepy as he lip-syncs. And he does this while wandering through the aisles of some kind of combination drug story and video game arcade, populated by a dozen or so women with deep tans, almost-white platinum-blonde wigs, and vinyl "sexy nurse" costumes in bright white with red trim, creating a dizzy collage of outdated pop culture signifiers jammed together strangely. It's the most ridiculous part of a ridiculous film, but it also feels like a distinct, comprehensible aesthetic project, the thing we can all hold onto and say that for two minutes, it's very easy to say what the film was doing - precisely because it's not "doing" anything besides just colliding audio and visual together, to no obvious meaning other than "well that's neat". And that is maybe the nastiest joke in this film full of sick humor: the easiest way to make sense of a nonsensical world that's tearing itself apart is to give into the nonsense and enjoy pure sensation. Is that also, necessarily, the "best" way? Southland Tales isn't telling: this film is good at diagnosing the crazy quilt world that birthed it, not "solving" it, because part of the diagnosis is that it's fundamentally insoluble. Bad satire? Sloppy storytelling? Yes, probably - but it's motherfucking gripping cinema.

*Yes, I know, the PATRIOT Act finally expired in the second half of 2020; the top-to-bottom rewiring of society it led to, I would argue, has not.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

To call Southland Tales a messy film would be like calling the Battle of Stalingrad a little scuffle, or the sinking of RMS Titanic an unfortunate yachting incident. It is one of the towering achievements of Messy Cinema. Director Richard Kelly's second feature, and the one with which he burned through literally all of the goodwill and studio indulgence he earned in making 2001's instant cult classic Donnie Darko, was here indulging himself at a level that we almost never see indulged, with the brash hunger of somebody who had achieved pretty much all the success any wannabe filmmaker dreams of achieving when he was all of 26 years old. This includes, among other things, positioning the film as the second half of a narrative that was begun in a series of three graphic novels, written during production and in the long months between the film's premiere and its wide release

It is a movie that does not feel like the word "no" was ever said in the course of its production, even when the filmmaker was perhaps deliberately trying to court that response. As he sort of was, according to his own version of the story, when he submitted the incomplete film to the Cannes International Film Festival for its 2006 edition, only to be shocked when the festival accepted it. And so a rushed and unfinished version of the film screened to one of the most hostile audiences in the history of that famously prickly and heckling-prone festival. Over a year later, a shorter cut with substantially different visual effects was released to theaters, where it met with bad reviews, total audience disinterest, and that was pretty much it for Richard Kelly; he had enough gas in the tank to make The Box in 2009, which met with ever so vaguely less hostile reviews, considerably more box office attention (but still not enough to make it profitable), and that is effectively where his career ends. Though he has popped up from time to time to announce projects that don't go anywhere.

I have two things to say about Southland Tales regarding its predominant role in immediately sending one of the hottest indie whiz kids of the early 2000s straight to a lifetime sentence in Director Jail. First, any studio executive who wanted to give this man more money in the wake of how he set $17 million on fire here would be a lunatic who should instantly be fired. Second: goddamn, what a way to go. This is the right way to murder a promising career, alright: with the kind of genuinely visionary work that feels beholden only the The Art Itself, a radical, swirling hallucination of ideas that all feel grabbed at random, but which cumulatively all seem to building to some kind of internally consistent declaration of how life and the universe works, centered around a passionately-felt theme. I admittedly don't entirely know what the declaration is saying or what the theme is; "man, I really hate that George W. Bush guy" is certainly part of it, and hey, I agree, he was a real nogoodnik. But it takes more to make a tight film than really hating that George W. Bush guy.

But how damn dare I tell Southland Tales its business. The exact thing that makes this such a vital treasure of a film is that it refuses to do any of the things that movies do, unless it stumbles into them by accident. Sometimes this means that the film gets trapped in long stretches of ideas that don't work or can't communicate themselves or feel just puerile, in the smug way of a smart kid who thinks he is much smarter still, and has a pretty crude and underdeveloped sense of humor that he thinks makes him a master satirist, on top of everything. I am sure, though, more sure than any other time that I have ever made this claim, that this is the price we have to pay for the places where the film is brilliant. Or, if not brilliant, so shockingly weird and bold and genuinely willing to risk absolute madness to find a new way of doing things that it at least makes this feel like a genuine one-off, in Kelly's career and in pretty much all of cinema.

The two cuts of Southland Tales - the Cannes cut was 159 minutes, the theatrical cut is 144 minutes, for the record, and both are readily available these days - present effectively identical stories with distinctly different moods, and since the mood of the film is considerably more important to the experience of watching it, we will need to talk about both to some extent. But in the interests of having a baseline to talk about, I suppose I should first approach the narrative, doing so with no small amount of appropriate wariness. "This is an epic Los Angeles crime saga", as we are told by Boxer Santaros (Dwayne Johnson, appearing for the first time without "The Rock" attached to his name), an amnesiac action film star and son-in-law of the Republican vice presidential candidate in the 2008 election. And he's only talking about the screenplay he's written with porn star turned aspiring cultural commentator Krysta Now (Sarah Michelle Gellar), but since that script turns out to be somehow prophetic in describing the events of the Southland Tales universe itself, we can borrow his terminology to describe this pre- and inter-apocalyptic story of Los Angeles in the brink of an abyss (the film makes a direct comparison between itself and the similarly doom-laden 1950s thriller Kiss Me Deadly, a film noir that's secretly about the inevitability of nuclear destruction). Boxer is being used as a pawn in at least two directions: Krysta has associations with a neo-Marxist radical group whose members include Krysta's porn director Cyndi Pinziki (Nora Dunn), avant garde poets Dream (Amy Poehler) and Dion (Wood Harris), and short-tempered fixer Zora Carmichaels (Cheri Oteri). And Boxer's mother-in-law Nana Mae Frost (Miranda Richardson) is head of the same government surveillance department that the neo-Marxists are hoping to destroy. There's another faction to consider: a team of visionary energy scientists led by Baron von Westphalen (Wallace Shawn), who shares a name and possibly a line of descent with Karl Marx's wife Jenny von Westphalen; other than "no good", it's tough to say what von Westphalen is up to with his posse of characters who are grotesque even by the standards this film sets for itself (the ones we need to worry about most are played by Bai Ling, Zelda Rubinstein, and Beth Grant; Kevin Smith eventually shows up, caked in latex and a giant grey beard, and this bit of stunt casting pushes Southland Tales fully into dream-logic derangement at the exact moment it needs that push). Floating around in all of this are identical twin brothers, Ronald and Roland Taverner (Sean William Scott), one an emotionally damaged ex-soldier, one a cop, both plagued by an inability to keep their identities straight, and a general feeling of being pressed upon by something much more cosmically troubling than the rise of anti-U.S. terrorist attacks and the expansion of the U.S. security state that most of the other characters are worried about. Because this is a Richard Kelly script, and he would never see fit to write a simple little political satire with like five different levels of cons, obfuscation, double-crossing, and disinformation without making sure the whole thing is a mindfuck about the nature of physical reality with a good dose of barely-comprehensible quantum mechanics underpinning the whole thing.

First things first: Southland Tales isn't a very smart political satire, though I do not know if it's fair to say that it's claiming otherwise. The film takes great joy in its crass humor, after all. Also, at the very broadest remove, the film's message is that the Right is evil, the Left is useless, and it won't matter soon since we'll all be dead in a (possibly nuclear) ecological catastrophe. Which may indeed be correct, but it's not smart satire. Anyway, the film knows, very clearly, that life in the United States under the Bush administration was sending everything to hell at top speed, and that has an awful lot to do with the extraordinary (and as we have since learned, irreversible*) erosion of privacy carried out through the passage of the PATRIOT Act. But look for a well-argued theory of political philosophy, and you will not find it.

Which I would say is both fine and, indeed, appropriate - Southland Tales is a movie, not an essay, and movies live in the realm of impression, emotion, sensation. And what this film is fantastic at, is capturing the feeling of a society in its death throes, where even the power brokers with an iron grip on the levers of government and industry are barely hanging together. Even the frequent incoherence of the narrative plays into this as a positive element, not just an error by a second-time director who got in over his head. Though it very well could have been such an error - not that it matters! The sheer chaos of the movie is the point, however Kelly got to it. But it goes beyond the script: every single thing about the film's construction, visually and dramatically, feeds into the overwhelming sense of a world that has broken past the point of repair. It's overstuffed with extraneous crap in the production design and art direction, some of which seems like it's trying to force some kind of symbolic meaning on the world, but never seems to actually create any sort of reliable pattern, just a series of erratic references to other things in this movie, and to things outside of it. The acting is fully of weirdly mannered performances, in which nearly every single actor was cast specifically because Kelly wanted them to things they had never established themselves capable of, and it's a crapshoot who actually succeeds in finding something to hold onto. Johnson, I would say, is a clear-cut winner here; it was his first chance to play things silly, and he thrived with things like the way he nervously flutters his fingers in what I can't help but read as an Oliver Hardy homage. It would be extremely hard to say anyone was doing their "best" work in this film, which has so little of what can be called straightforward character material, but it is my "favorite" of Johnson's movie performances. But anyway, part of the pleasure of the thing is that everybody is attack the script in their own way, with everything from Oteri's over-the-top yelling to Richardson sinking into stillness and a loose Texan drawl to Shawn having a great time going fully into camp as a way of coping with his utter bafflement as to the script's meaning. And these all feel like equally valid ways of trying to find some anchor in the middle of events they can by no means control.

The editing of the two cuts of Southland Tales functions a bit differently in this regard, such that I can't really call one of them "better". There's only one significant narrative change: a scene of von Westphalen gleefully betraying a Japanese business partner more or less opened the original cut, giving us an immediate sense of his viciousness and the overall level of apocalyptic lawlessness and violence that rules this world; the theatrical cut moves it back by over an hour. Otherwise, the difference is in textures and atmosphere. For one thing, the theatrical cut is less overtly comic: Janeane Garofalo's performance, the most conventionally funny part of the original cut, has been reduced to little more than a glancing cameo in the shorter version. And there are smaller places where a different choice of take, or cutting out individual lines, softens the impact of the more overt gags. The theatrical cut loses some of the connective tissue, giving a more fragmentary feeling to the narrative: it is a bit more blunt about what's going on, with several lines of voiceover narrative added to clearly indicate things that were a bit vague originally. It's sharper, not in the sense of being precise, but in the sense that it feels like you could cut yourself on it.

The Cannes cut, in contrast, is dreamier and more diffuse: almost exclusively in the opening, but part of the way movies work is by giving us first impressions that color our entire experience. The presentation of the backstory is more like a fable, more ambiguous; an opening montage of home video footage showing a nuclear bomb strike Abilene, Texas on 4 July, 2005 goes on much longer in the Cannes cut before the bombs go off, and the footage is window-boxed within the 2.35:1 frame, making it a little distant from us. Even the appearance of the word "Abilene" onscreen is vaguer in the Cannes cut: it both points at the town where this took place, but also serves to introduce our narrator, Pilot Abilene (Justin Timberlake). This double-meaning is lost in the theatrical cut. And Abilene's narration is itself different: Kelly had Timberlake re-record all of it to pin down a different mood for the theatrical cut, something more normal. In the Cannes cut, Timberlake's tone of voice is lilting and dreamy, almost feminine in its cadences, and it instantly creates a much hazier vibe than anything in the theatrical cut ever achieves, or tries for. Meanwhile, while the longer cut explains less, it shows more, and the slower development of the film's first third, especially, makes it a little easier to place ourselves physically in the movie, if not narratively.

Either way, the end result is similar enough: a world gone mad needs a film to go mad with it. This is most overwhelming in the end, when Kelly goes all-in on visionary sci-fi madness, but it's also there right from the start, in the visually noisy news report that the film throws at us with no sign of how we're meant to read it, or figure out what is exposition, what is world-building, and what's just extraneous.

The best sign of the overall approach Southland Tales takes, I think, is that the scene where it most feels like it "clicks", and the scene that Kelly apparently regarded as the heart of the entire project, is at best a narratively inconsequential drug hallucination, and might very well take place entirely outside of the film's diegesis altogether: shortly after the film's midway point, Pilot Abilene finally enters the movie in the flesh in a significant way, to shoot himself up with some sci-fi drug, and thence to star in a music video for about half of the Killers song "All These Things That I've Done". The camera glides along, leading Timberlake as he stares uncomfortably into the lens, looking surly and sleepy as he lip-syncs. And he does this while wandering through the aisles of some kind of combination drug story and video game arcade, populated by a dozen or so women with deep tans, almost-white platinum-blonde wigs, and vinyl "sexy nurse" costumes in bright white with red trim, creating a dizzy collage of outdated pop culture signifiers jammed together strangely. It's the most ridiculous part of a ridiculous film, but it also feels like a distinct, comprehensible aesthetic project, the thing we can all hold onto and say that for two minutes, it's very easy to say what the film was doing - precisely because it's not "doing" anything besides just colliding audio and visual together, to no obvious meaning other than "well that's neat". And that is maybe the nastiest joke in this film full of sick humor: the easiest way to make sense of a nonsensical world that's tearing itself apart is to give into the nonsense and enjoy pure sensation. Is that also, necessarily, the "best" way? Southland Tales isn't telling: this film is good at diagnosing the crazy quilt world that birthed it, not "solving" it, because part of the diagnosis is that it's fundamentally insoluble. Bad satire? Sloppy storytelling? Yes, probably - but it's motherfucking gripping cinema.

*Yes, I know, the PATRIOT Act finally expired in the second half of 2020; the top-to-bottom rewiring of society it led to, I would argue, has not.