House of the dead

Since the moment that the first Resident Evil film appeared way back in 2002, that movie and its five sequels have come under attack from fans of the video game series, on the charges of reckless infidelity to the source material. To be entirely fair, they also have come under attack from critics and audiences for being awful, tacky garbage, but that's a different argument. The first group of attackers now has cause to celebrate, in theory, since Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City is exactly the faithful adaptation that Resident Evil and its children so emphatically weren't this new film starts the series entirely from scratch with a script that pretty closely hews to the first two video games in the series, from 1996 and 1998, doing away entirely with any superpowered clones named Alice or ultra high-tech underground bunkers full of lasers and pissy A.I. children.

In so doing, Welcome to Raccoon City proves that what we want and what we need are not always the same thing. The 2002 Resident Evil is hard to defend as a genuinely good film, and some of its sequels are much harder to so defend, but what cannot be denied is that it is lively. Director Paul W.S. Anderson's flair for gee-whiz idiocy, and his peerless ability to frame Milla Jovovich as the coolest motherfucking badass in the history of action cinema, combine to make the first film, at the very least, a joyous plunge into unapologetically gaudy genre trash: nearly two decades later, the hallway with a checkerboard laser trap that turns humans into cubes of meat is still one of the most indelible conceits in 21st Century horror filmmaking. The Anderson Resident Evils a triumphs of what happens when a filmmaker doesn't sweat the source material too much, but just goes for whatever loopy ideas seem like they can be fitted into the basic concept, approaching the project as a movie first, an adaptation second.

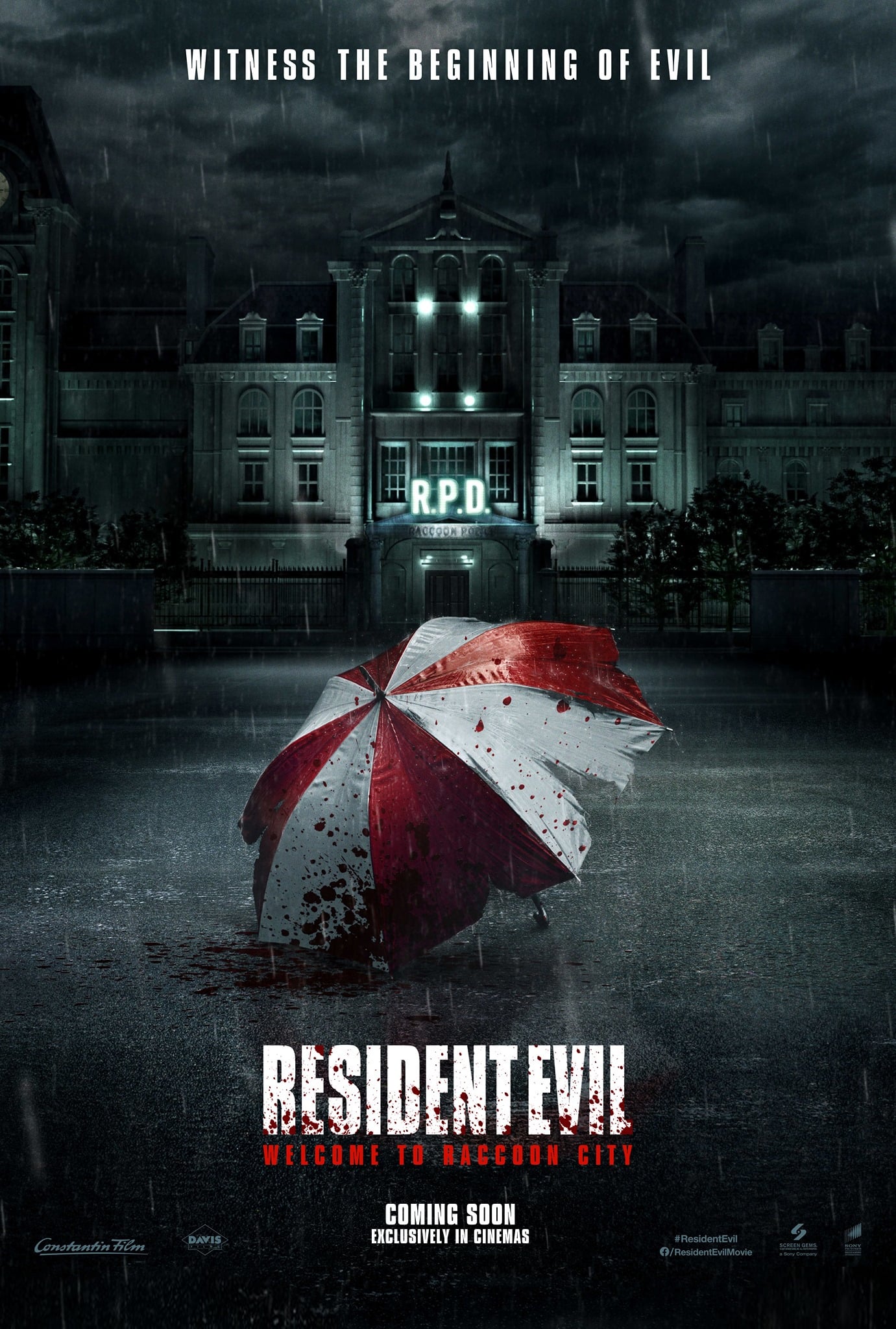

This is grimly reinforced by Welcome to Raccoon Cinema, which is about as joyous as a power outage while you're doing your taxes. Writer-director Johannes Roberts is clearly trying to make sure he covers the games as thoroughly as he can, which in practice ends up feeling like he's not telling a story so much as working his way down a checklist. This is most loudly apparent in the film's gravely functional dialogue, the kind in which characters fussily and unnecessarily say everybody's name including their own, so you can know for sure that all your favorites are here. Put it this way: "Hello, Jill Valentine, I'm Leon Kennedy" isn't an exact quote from the movie, but it's a pretty close paraphrase. The same feeling applies to pretty much everything else, including the story, which progresses according to the exact logic of moving from one level to the next and solving puzzles to advance, and the production design, which ritualistically re-creates locations from the game, even when the idea behind those locations makes more "video game" sense than "this place seems like it would plausibly exist" sense.

The basics of the story: several years ago, Claire Redfield (Kaya Scodelario) escaped from a menacing orphanage in Raccoon City. Now, in 1998, she's come back, for reasons that are at first mysterious; we eventually learn that she's been communicating with a weird conspiracy theorist who is convinced that something terrible is about to happen in town, and Claire has arrived to warn her estranged brother Chris (Robbie Amell), now a member of the Raccoon Police Department, to get the hell out. Sadly, Claire's timing is off: the residents of Raccoon City, all except the cops, have already been showing signs of something bad happening: they're afflicted with health problems, involving blood oozing where blood oughtn't, hair falling out, skin turning scaly, all sorts of things that make you look like a tottering zombie. Spoiler alert.

This has most recently manifest as problems at the old Spencer Mansion, where the team sent to investigate some dead bodies has gone missing. So now police chief Irons (Donal Logue) has to send two player characters and some expendable NPCs to penetrate the mansion: Chris Redfield, Jill Valentine (Hannah John-Kamen), Albert Wesker (Tom Hopper), Richard Aiken (Chad Rook), and helicopter pilot Brad Vickers (Nathan Dales). They end up having to fight zombies in the mansion, while Claire Redfield ends up at the police station with Irons and rookie Leon S. Kennedy (Avan Jogia), defending that location from other zombies. Meanwhile, mad pharmaceutical scientist William Birkin (Neal McDonough), of the Umbrella Corporation, whose machinations are responsible for transforming the good men and women of Raccoon City into cannibalistic monsters, has put into motion a plan that will blow up the whole town at 6:00 AM.

In ushering us through all of this, Roberts has clearly focused first and above all on including everything, whether by his own will or the demands of the producers. He has only second, or indeed not at all, focused on making any of this even a little tiny bit interesting to watch. The downside of building an entire film around plot beats from the games is that there's never a sense that the filmmakers here actually thought about why those beats need to happen, so there's no logic to how the story advances, other than "this is how it's supposed to go". This is most oppressively true in the case of the year this takes place, 1998. Need it take place in 1998? Not for any reason I can figure out, though it's not like it can't. Movies take place in arbitrary years all the time. But somehow, despite the sum total of the significance of 1998 being "that's when Resident Evil 2 came out", Roberts and company have decided that it is crucially important that we keep being hammered over the head with 1998 signifiers. Such as Claire's laborious discussion of how "chat rooms" work on "the internet". Or a real barnburner of a line of dialogue, in which one character mocks another character's plans by saying something like "Maybe you can go on a date to Planet Hollywood. If that doesn't work out, you could already rent a video at Blockbuster". I am again paraphrasing, and again it's only by a little bit.

It's bad enough that we're lifelessly grinding through a thoughtless narrative collage, but Welcome to Raccoon City has a built in means of coping with that: throw some zombies into creepy, underlit building, and have them jump out at characters. Astonishingly it refuses to do this. Oh, there are zombies, and all, but given that the whole "thing" of the Resident Evil franchise is the grotesque perversions of human bodies that have been corrupted by Umbrella's bioweapons, it is positively indecent how many of the film's 107 minutes have gone by before we see any zombies more viscerally designed than just regular humans with grey skin and thinning hair. Slow boils are nice, and all, but Raccoon City doesn't have any heat underneath in the first place. To its credit, around the point, a good hour or more into it, when it finally returns to the creepy old orphanage and CGI abominations start to attack Claire, the film does manages to rise up to the level of a pleasingly disgusting time-waster. The climax even manages to approach an Anderson-esque level of unapologetic stupidity in how it stages the boss fight, and how randomly that fight is wrapped up. It also features some monster designs that are, if not genuinely creepy, at least admirably disgusting.

That comes at the end of a whole lot of waving flashlights around in dark rooms and traipsing through some pretty horrible dialogue writing. Roberts isn't a hapless filmmaker, and in 2018's The Strangers: Prey at Night, he demonstrated a certain flair for atmosphere. And this isn't completely missing from Welcome to Raccoon City. There's a pretty swell sequence lit only by muzzle flashes, with the approach of a zombie marked out by a series of increasingly close glimpses of its dead face. And there's a less swell, but at least adequately tense scene in a parking garage, where bangs and scuffling have been cranked up on the soundtrack to nerve-tingling levels.

Mostly, though, this isn't even good at atmosphere. The spaces are either inexplicably designed (the police department, with its courtyard behind a wrought-iron gate), or too desperate to show off how good-golly creepy they are (the old orphanage, the falling-apart laboratories beneath the mansion), and in neither case is it possible just to sink into the cheap thrills of dim lighting and twitching corpses. The only other trick Roberts has is to throw out a whole mess of music cues - another Prey at Night move, here used so often that it feels like a compulsion (including a scene set to "What's Up?" by 4 Non Blondes that's one of the most uncommitted and half-assed examples of ironic pop song counterpoint that I have ever witnessed).

The film that emerges from all of this is worse than bad: it is dreary. It's slow moving, the only good visual ideas are backloaded, and there are too many characters with ill-defined personalities to keep track of. Scodelario is the only person producing enough of a personality through her acting that she actually seems to exist as anything other than a sneer and a gun (McDonough does fine with what he's got, but he's barely in the movie). The whole thing is perfunctory, a work of accounting as much as it is a work of filmmaking. It's not news that zombie movies can be boring as they just go through the motions, of course, but this zombie movie has to compete directly with the memories of Anderson's goofball popcorn spectacle, and that considerably amplifies just how dead it feels.

In so doing, Welcome to Raccoon City proves that what we want and what we need are not always the same thing. The 2002 Resident Evil is hard to defend as a genuinely good film, and some of its sequels are much harder to so defend, but what cannot be denied is that it is lively. Director Paul W.S. Anderson's flair for gee-whiz idiocy, and his peerless ability to frame Milla Jovovich as the coolest motherfucking badass in the history of action cinema, combine to make the first film, at the very least, a joyous plunge into unapologetically gaudy genre trash: nearly two decades later, the hallway with a checkerboard laser trap that turns humans into cubes of meat is still one of the most indelible conceits in 21st Century horror filmmaking. The Anderson Resident Evils a triumphs of what happens when a filmmaker doesn't sweat the source material too much, but just goes for whatever loopy ideas seem like they can be fitted into the basic concept, approaching the project as a movie first, an adaptation second.

This is grimly reinforced by Welcome to Raccoon Cinema, which is about as joyous as a power outage while you're doing your taxes. Writer-director Johannes Roberts is clearly trying to make sure he covers the games as thoroughly as he can, which in practice ends up feeling like he's not telling a story so much as working his way down a checklist. This is most loudly apparent in the film's gravely functional dialogue, the kind in which characters fussily and unnecessarily say everybody's name including their own, so you can know for sure that all your favorites are here. Put it this way: "Hello, Jill Valentine, I'm Leon Kennedy" isn't an exact quote from the movie, but it's a pretty close paraphrase. The same feeling applies to pretty much everything else, including the story, which progresses according to the exact logic of moving from one level to the next and solving puzzles to advance, and the production design, which ritualistically re-creates locations from the game, even when the idea behind those locations makes more "video game" sense than "this place seems like it would plausibly exist" sense.

The basics of the story: several years ago, Claire Redfield (Kaya Scodelario) escaped from a menacing orphanage in Raccoon City. Now, in 1998, she's come back, for reasons that are at first mysterious; we eventually learn that she's been communicating with a weird conspiracy theorist who is convinced that something terrible is about to happen in town, and Claire has arrived to warn her estranged brother Chris (Robbie Amell), now a member of the Raccoon Police Department, to get the hell out. Sadly, Claire's timing is off: the residents of Raccoon City, all except the cops, have already been showing signs of something bad happening: they're afflicted with health problems, involving blood oozing where blood oughtn't, hair falling out, skin turning scaly, all sorts of things that make you look like a tottering zombie. Spoiler alert.

This has most recently manifest as problems at the old Spencer Mansion, where the team sent to investigate some dead bodies has gone missing. So now police chief Irons (Donal Logue) has to send two player characters and some expendable NPCs to penetrate the mansion: Chris Redfield, Jill Valentine (Hannah John-Kamen), Albert Wesker (Tom Hopper), Richard Aiken (Chad Rook), and helicopter pilot Brad Vickers (Nathan Dales). They end up having to fight zombies in the mansion, while Claire Redfield ends up at the police station with Irons and rookie Leon S. Kennedy (Avan Jogia), defending that location from other zombies. Meanwhile, mad pharmaceutical scientist William Birkin (Neal McDonough), of the Umbrella Corporation, whose machinations are responsible for transforming the good men and women of Raccoon City into cannibalistic monsters, has put into motion a plan that will blow up the whole town at 6:00 AM.

In ushering us through all of this, Roberts has clearly focused first and above all on including everything, whether by his own will or the demands of the producers. He has only second, or indeed not at all, focused on making any of this even a little tiny bit interesting to watch. The downside of building an entire film around plot beats from the games is that there's never a sense that the filmmakers here actually thought about why those beats need to happen, so there's no logic to how the story advances, other than "this is how it's supposed to go". This is most oppressively true in the case of the year this takes place, 1998. Need it take place in 1998? Not for any reason I can figure out, though it's not like it can't. Movies take place in arbitrary years all the time. But somehow, despite the sum total of the significance of 1998 being "that's when Resident Evil 2 came out", Roberts and company have decided that it is crucially important that we keep being hammered over the head with 1998 signifiers. Such as Claire's laborious discussion of how "chat rooms" work on "the internet". Or a real barnburner of a line of dialogue, in which one character mocks another character's plans by saying something like "Maybe you can go on a date to Planet Hollywood. If that doesn't work out, you could already rent a video at Blockbuster". I am again paraphrasing, and again it's only by a little bit.

It's bad enough that we're lifelessly grinding through a thoughtless narrative collage, but Welcome to Raccoon City has a built in means of coping with that: throw some zombies into creepy, underlit building, and have them jump out at characters. Astonishingly it refuses to do this. Oh, there are zombies, and all, but given that the whole "thing" of the Resident Evil franchise is the grotesque perversions of human bodies that have been corrupted by Umbrella's bioweapons, it is positively indecent how many of the film's 107 minutes have gone by before we see any zombies more viscerally designed than just regular humans with grey skin and thinning hair. Slow boils are nice, and all, but Raccoon City doesn't have any heat underneath in the first place. To its credit, around the point, a good hour or more into it, when it finally returns to the creepy old orphanage and CGI abominations start to attack Claire, the film does manages to rise up to the level of a pleasingly disgusting time-waster. The climax even manages to approach an Anderson-esque level of unapologetic stupidity in how it stages the boss fight, and how randomly that fight is wrapped up. It also features some monster designs that are, if not genuinely creepy, at least admirably disgusting.

That comes at the end of a whole lot of waving flashlights around in dark rooms and traipsing through some pretty horrible dialogue writing. Roberts isn't a hapless filmmaker, and in 2018's The Strangers: Prey at Night, he demonstrated a certain flair for atmosphere. And this isn't completely missing from Welcome to Raccoon City. There's a pretty swell sequence lit only by muzzle flashes, with the approach of a zombie marked out by a series of increasingly close glimpses of its dead face. And there's a less swell, but at least adequately tense scene in a parking garage, where bangs and scuffling have been cranked up on the soundtrack to nerve-tingling levels.

Mostly, though, this isn't even good at atmosphere. The spaces are either inexplicably designed (the police department, with its courtyard behind a wrought-iron gate), or too desperate to show off how good-golly creepy they are (the old orphanage, the falling-apart laboratories beneath the mansion), and in neither case is it possible just to sink into the cheap thrills of dim lighting and twitching corpses. The only other trick Roberts has is to throw out a whole mess of music cues - another Prey at Night move, here used so often that it feels like a compulsion (including a scene set to "What's Up?" by 4 Non Blondes that's one of the most uncommitted and half-assed examples of ironic pop song counterpoint that I have ever witnessed).

The film that emerges from all of this is worse than bad: it is dreary. It's slow moving, the only good visual ideas are backloaded, and there are too many characters with ill-defined personalities to keep track of. Scodelario is the only person producing enough of a personality through her acting that she actually seems to exist as anything other than a sneer and a gun (McDonough does fine with what he's got, but he's barely in the movie). The whole thing is perfunctory, a work of accounting as much as it is a work of filmmaking. It's not news that zombie movies can be boring as they just go through the motions, of course, but this zombie movie has to compete directly with the memories of Anderson's goofball popcorn spectacle, and that considerably amplifies just how dead it feels.