Come to Jesus

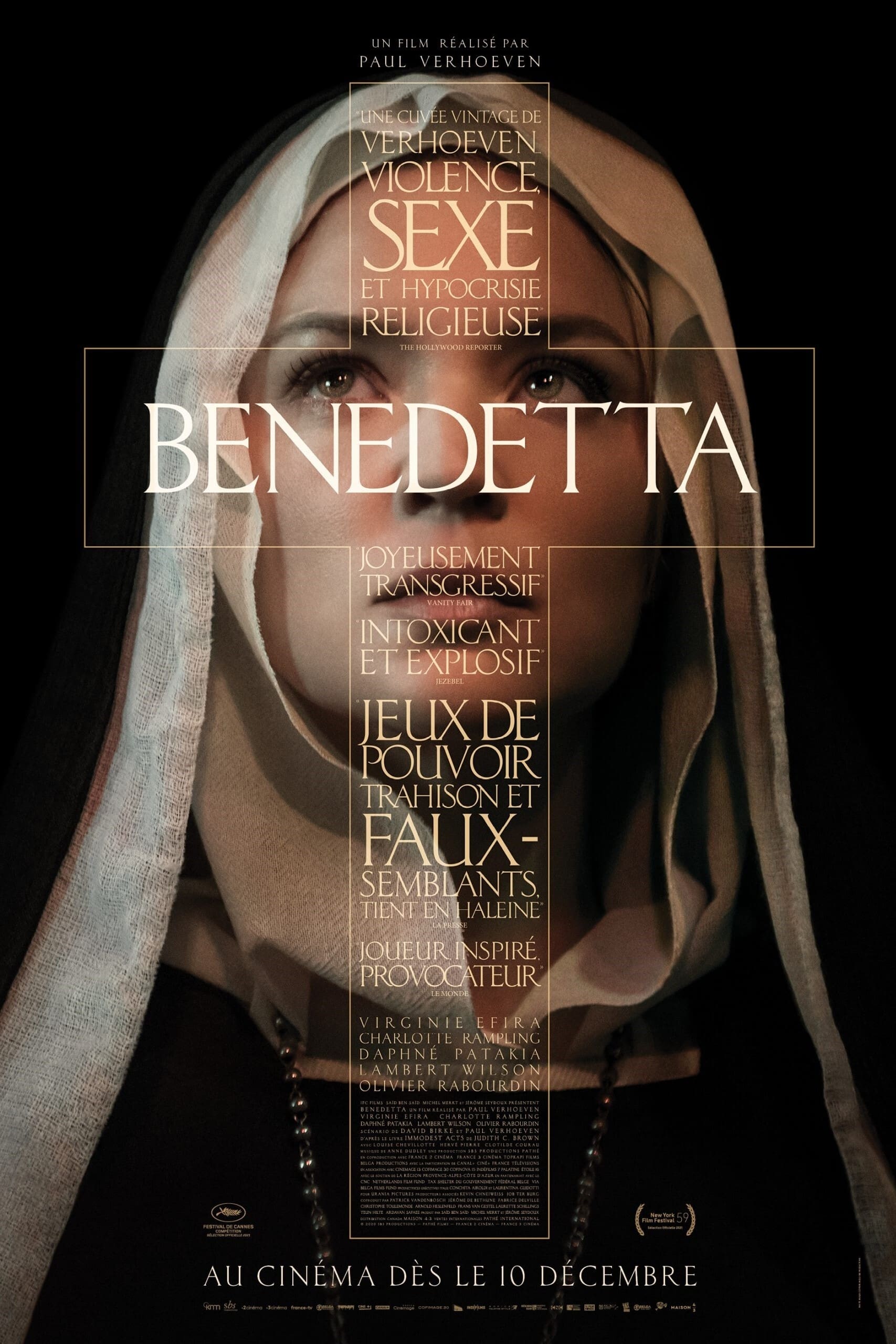

Benedetta, a film about lesbian nuns directed by Paul Verhoven, is a very different thing than "a film about lesbian nuns directed by Paul Verhoeven" can even start to suggest. One of the most shocking, provocative things about it is that it puts almost no effort into being provocative or shocking. It satirically targets the hierarchy of the Catholic church while taking matters of faith and the divine quite seriously. I hesitate to say that it feels like Verhoeven's most "mature" film - it premiered at the 2021 Cannes International Film Festival just over a week prior to his 82nd birthday, I think we can assume we've been getting "mature" Verhoeven films for a good long while now - but it is at least a more restrained and sedate Verhoeven film than we typically get from him. It is also a film in which one of the lesbian nuns gives the other lesbian nun a small carving of the Virgin Mary, one end of which has been whittled and shaped into a rounded nub to serve as a dildo. So "sedate" is relative. But still.

The film is taken from the historical book Immodest Acts by Judith C. Brown; it is, in fact, a tolerably accurate version of what happened in the first quarter of the 17th Century in the town of Pescia, Italy, accommodating for the fact that the film seems to very aggressively compress the timeline, down from about six years. We first meet Benedetta as a child (Elena Plonka), when her parents (David Clavel, Clotilde Courau) deposit her at the convent in Pescia, Tuscany, and in the process get our first clear view of what Verhoeven and his co-writer David Birke want to do with the the film, which as it will turn out is more incidentally about lesbian nuns than anything. When Benedetta's parents meet the abbess (Charlotte Rampling), she greats them with a beatific smile, warm demeanor, and a sorrowful confession that it might be awfully hard to fit their daughter in, given the high demand. So they offer her money. So far, so much like all the ordinary "the Church had become a hypocritical vehicle for moneymaking and wheedling" satires out there. The kicker comes when the abbess suggests, in exactly the same tone, that it seems awfully unfair for the parents to offer the convent such a small total when she knows quite well what the dowry of a child in Benedetta's position on the open market would go for.

It's still sort of a typical moment, but something about it feels just very, very distinctive. Rampling's performance undoubtedly has a great deal to do with this, and indeed all throughout Benedetta, her presence is one of the greatest strengths. She exudes calculating pragmatism, giving us the spectacle of a brilliant woman, whose brilliance has been capped out at a set height by the built-in hierarchies of the Church and its general disdain for women with authority, making conscious, difficult decisions in front of our eyes. And these are not always decisions for her own immediate power - at a certain point around the middle of the film, the abbess's power is reduced and she becomes simple Sister Felicita, and a great deal of what makes this transition fascinating is how Rampling makes sure that we see how her character makes the calculation that this is the correct path, and how she avoids the simple portrayal of a bruised ego and jealous old woman that would be easily supported by the script and the further development of the conflict.

Rampling's performance as the abbess superbly anchors Benedetta in the vulgarity of Church realpolitik, one of the film's main interests. But trying to pin it down to just one branch of its plot would be impossible: this is an overstuffed collection of ideas, both narrative and visual, that's equally as invested in portraying the intensity of two young people falling in lust, and in following the visions experienced by Benedetta herself after she's grown into her twenties (Virginia Efira). Benedetta is a decidedly secular, even materialist film, yet it also takes for granted that Benedetta's mystic experiences are a serious matter, and that we need to keep open the possibility that they're real. These include multiple appearances of stigmata, as well as dream visions where Benedetta meets with smoldering, sexy Jesus (Jonathan Couzinié), where the film's generally realistic aesthetic is dropped for slicky, painfully shiny digital images pushed by cinematographer Jeanne Lapoirie into a scrubbed artifice that's a perfect contrast to the dusty realism and natural light we see elsewhere.

Benedetta is very ambivalent about how much it wants to let us inside Benedetta's head. We see those visions and hear the sounds, but we're left with the same questions as the two two other main characters, the abbess and novice Bartolomea (Daphné Patakia), who ends up becoming her lover: are these phenomena real? Are they purely an attempt by the young woman to jockey for power in a hierarchy where she'd never succeed otherwise? Is she truly moved by the Holy Spirit, and any fakery or deception on her part is merely an attempt to bring the word of God into the compromised world of humans? Benedetta leaves all of those possibilities open, and isn't so much interested in speculating on the answers as it is in exploring what it means to be alive in a world where those questions could all be asked simultaneously.

This ultimately means that the film is grounded in an attempt to make daily life in the early 17th Century feel urgent and present and modern, and it does this by threading the very tiniest needle: on the one hand, Benedetta completely eschews the stiff elegance of so many costume dramas. It's a movie full of living, fleshy people, something it establishes early on with some excessively crude scatological jokes, including a scene set in an indoor privy where the function of such a room is given quite a substantial discussion in the dialogue, and quite an alarmingly detailed presence in the sound mix. The sex scenes between Efira and Patakia are similarly honest about how the body works, though never explicit and not played for laughs. The film is in fact a surprisingly sincere love story, or at least it surprised me (that's just about the only part of this bawdy, sarcastic project that is sincere; another surprise-I-should-have-expected is that Benedetta is often a very funny movie). On the other hand, it is unambiguously not a film about modern people, even with the same-sex romance: the everyday logic they take for granted is unrecognisably mired in a world where a nun having mystic visions feels like something that can just happen, and nobody questions the plausibility of Benedetta's visions, just whether or not she's actually telling the truth about them. It unexpectedly reminded me, of Verhoven's first-ever film in English, Flesh+Blood from 1985, which has a similarly blunt, grossly unromantic vision of life in the world of costume dramas, while positioning itself in the moral headspace of the people who actually lived in history.

Benedetta is the stronger of the two films, with a more expansive emotional palette to work with, and three fantastic lead performances to filter those emotions through: in some ways, Efira is actually the least-interesting, since so much of what she has to do is play Benedetta's surface, while Rampling and Patakia are able to play what their characters are thinking and not saying. This creates a sense, I don't think accidentally, that the film is mostly about how other people see Benedetta, what things they put upon her based on their own preoccupations. For the abbess, she's a political tool that could be dangerous if the wrong people take her seriously. For Bartolomea, hungrily secular and desperate for love, she's an object to cherish, a body to lust after, a warm presence to comfort and feel comforted by. This leaves Benedetta's religious ecstasy to be felt only by herself, and we don't have complete access to her, so the film has to just sit by watching agnostically, wondering at that ecstasy but never knowing how to take part of it.

It's all wonderfully strange and sprawling: filthy and fleshy, dreamy and spiritual, hilarious and biting. This is all pulled together in the end; Verhoeven's films often feel like they're about to split apart from all the things crammed inside of them, but he is an old hand at directing movies, and Benedetta is one of his tightest and most focused ever, 131 minutes that breeze by as the film keeps switching moods to make it so it feels almost on a scene by scene basis that we can't guess what's coming until it shows up. It's a very lively film, and that is perhaps the best thing about it: sex and religion and power and the foreign country that is the past are all good things to intellectualise and ponder, but Benedetta's great triumph is in proving that all of this can simultaneously be watchable - delectably so.

The film is taken from the historical book Immodest Acts by Judith C. Brown; it is, in fact, a tolerably accurate version of what happened in the first quarter of the 17th Century in the town of Pescia, Italy, accommodating for the fact that the film seems to very aggressively compress the timeline, down from about six years. We first meet Benedetta as a child (Elena Plonka), when her parents (David Clavel, Clotilde Courau) deposit her at the convent in Pescia, Tuscany, and in the process get our first clear view of what Verhoeven and his co-writer David Birke want to do with the the film, which as it will turn out is more incidentally about lesbian nuns than anything. When Benedetta's parents meet the abbess (Charlotte Rampling), she greats them with a beatific smile, warm demeanor, and a sorrowful confession that it might be awfully hard to fit their daughter in, given the high demand. So they offer her money. So far, so much like all the ordinary "the Church had become a hypocritical vehicle for moneymaking and wheedling" satires out there. The kicker comes when the abbess suggests, in exactly the same tone, that it seems awfully unfair for the parents to offer the convent such a small total when she knows quite well what the dowry of a child in Benedetta's position on the open market would go for.

It's still sort of a typical moment, but something about it feels just very, very distinctive. Rampling's performance undoubtedly has a great deal to do with this, and indeed all throughout Benedetta, her presence is one of the greatest strengths. She exudes calculating pragmatism, giving us the spectacle of a brilliant woman, whose brilliance has been capped out at a set height by the built-in hierarchies of the Church and its general disdain for women with authority, making conscious, difficult decisions in front of our eyes. And these are not always decisions for her own immediate power - at a certain point around the middle of the film, the abbess's power is reduced and she becomes simple Sister Felicita, and a great deal of what makes this transition fascinating is how Rampling makes sure that we see how her character makes the calculation that this is the correct path, and how she avoids the simple portrayal of a bruised ego and jealous old woman that would be easily supported by the script and the further development of the conflict.

Rampling's performance as the abbess superbly anchors Benedetta in the vulgarity of Church realpolitik, one of the film's main interests. But trying to pin it down to just one branch of its plot would be impossible: this is an overstuffed collection of ideas, both narrative and visual, that's equally as invested in portraying the intensity of two young people falling in lust, and in following the visions experienced by Benedetta herself after she's grown into her twenties (Virginia Efira). Benedetta is a decidedly secular, even materialist film, yet it also takes for granted that Benedetta's mystic experiences are a serious matter, and that we need to keep open the possibility that they're real. These include multiple appearances of stigmata, as well as dream visions where Benedetta meets with smoldering, sexy Jesus (Jonathan Couzinié), where the film's generally realistic aesthetic is dropped for slicky, painfully shiny digital images pushed by cinematographer Jeanne Lapoirie into a scrubbed artifice that's a perfect contrast to the dusty realism and natural light we see elsewhere.

Benedetta is very ambivalent about how much it wants to let us inside Benedetta's head. We see those visions and hear the sounds, but we're left with the same questions as the two two other main characters, the abbess and novice Bartolomea (Daphné Patakia), who ends up becoming her lover: are these phenomena real? Are they purely an attempt by the young woman to jockey for power in a hierarchy where she'd never succeed otherwise? Is she truly moved by the Holy Spirit, and any fakery or deception on her part is merely an attempt to bring the word of God into the compromised world of humans? Benedetta leaves all of those possibilities open, and isn't so much interested in speculating on the answers as it is in exploring what it means to be alive in a world where those questions could all be asked simultaneously.

This ultimately means that the film is grounded in an attempt to make daily life in the early 17th Century feel urgent and present and modern, and it does this by threading the very tiniest needle: on the one hand, Benedetta completely eschews the stiff elegance of so many costume dramas. It's a movie full of living, fleshy people, something it establishes early on with some excessively crude scatological jokes, including a scene set in an indoor privy where the function of such a room is given quite a substantial discussion in the dialogue, and quite an alarmingly detailed presence in the sound mix. The sex scenes between Efira and Patakia are similarly honest about how the body works, though never explicit and not played for laughs. The film is in fact a surprisingly sincere love story, or at least it surprised me (that's just about the only part of this bawdy, sarcastic project that is sincere; another surprise-I-should-have-expected is that Benedetta is often a very funny movie). On the other hand, it is unambiguously not a film about modern people, even with the same-sex romance: the everyday logic they take for granted is unrecognisably mired in a world where a nun having mystic visions feels like something that can just happen, and nobody questions the plausibility of Benedetta's visions, just whether or not she's actually telling the truth about them. It unexpectedly reminded me, of Verhoven's first-ever film in English, Flesh+Blood from 1985, which has a similarly blunt, grossly unromantic vision of life in the world of costume dramas, while positioning itself in the moral headspace of the people who actually lived in history.

Benedetta is the stronger of the two films, with a more expansive emotional palette to work with, and three fantastic lead performances to filter those emotions through: in some ways, Efira is actually the least-interesting, since so much of what she has to do is play Benedetta's surface, while Rampling and Patakia are able to play what their characters are thinking and not saying. This creates a sense, I don't think accidentally, that the film is mostly about how other people see Benedetta, what things they put upon her based on their own preoccupations. For the abbess, she's a political tool that could be dangerous if the wrong people take her seriously. For Bartolomea, hungrily secular and desperate for love, she's an object to cherish, a body to lust after, a warm presence to comfort and feel comforted by. This leaves Benedetta's religious ecstasy to be felt only by herself, and we don't have complete access to her, so the film has to just sit by watching agnostically, wondering at that ecstasy but never knowing how to take part of it.

It's all wonderfully strange and sprawling: filthy and fleshy, dreamy and spiritual, hilarious and biting. This is all pulled together in the end; Verhoeven's films often feel like they're about to split apart from all the things crammed inside of them, but he is an old hand at directing movies, and Benedetta is one of his tightest and most focused ever, 131 minutes that breeze by as the film keeps switching moods to make it so it feels almost on a scene by scene basis that we can't guess what's coming until it shows up. It's a very lively film, and that is perhaps the best thing about it: sex and religion and power and the foreign country that is the past are all good things to intellectualise and ponder, but Benedetta's great triumph is in proving that all of this can simultaneously be watchable - delectably so.