Bergman x Bergman

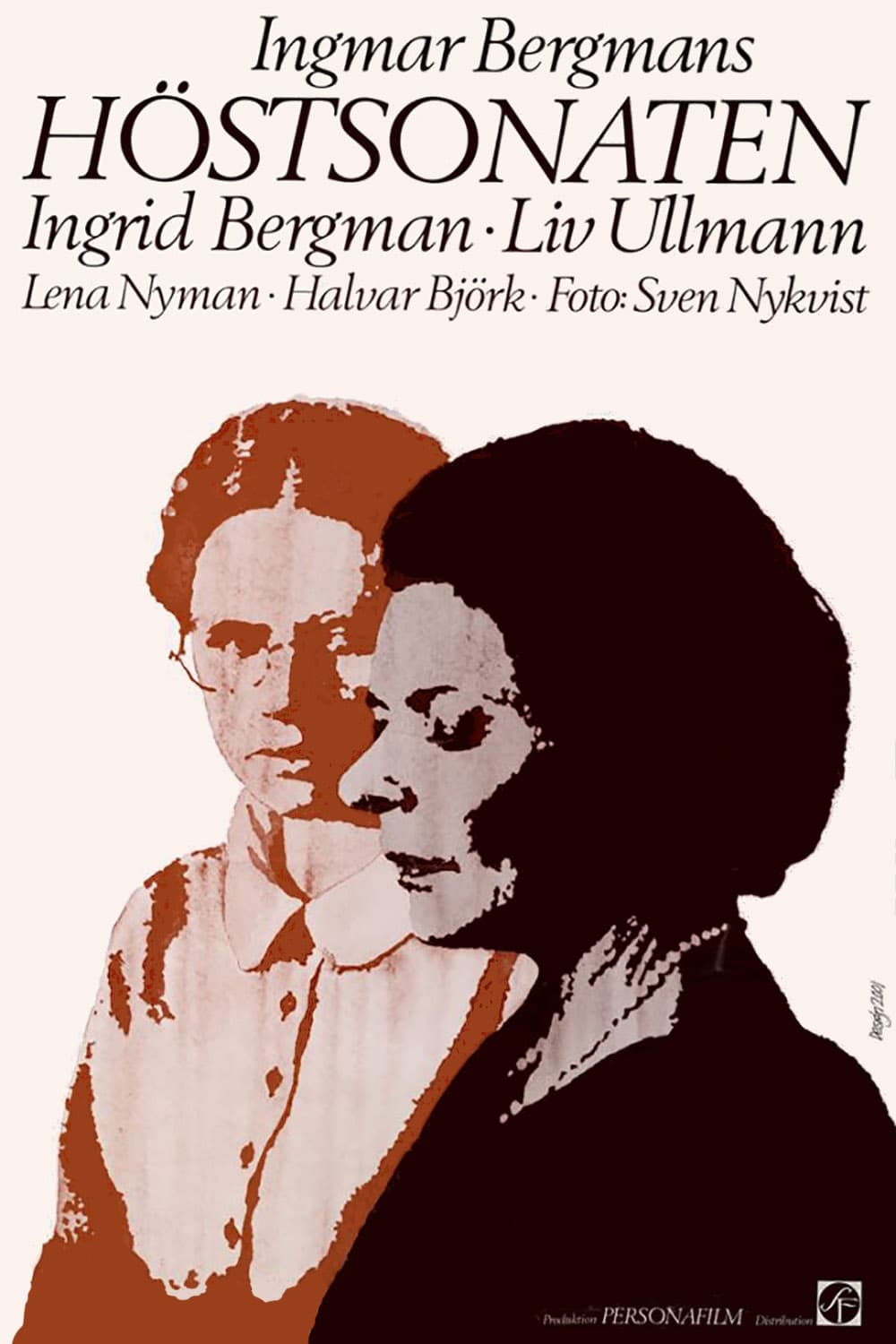

One cannot grapple with 1978 Autumn Sonata, not in any of the ways it's doing pretty much anything, without going straight to the most blazingly obvious. This is, before it is anything else, the single collaboration between the two most internationally famous representatives of the Swedish film industry,* the one where iconic AAA-level Hollywood movie star Ingrid Bergman and legendary art house director Ingmar Bergman pooled their talents in a film that has, ironically, not a single öre of Swedish money it (if I have the story right, it was a West German company taking money from the United Kingdom to film at an old studio in Norway). This means, among other things, that if I am to write a review that can be even remotely understood, I have to write something other than their last name (they were not, for the record, related), which means you'll see a lot of "Ingrid did this", "Ingmar did that" for the rest of this piece, like I'm their most intimate buddy, or some damn thing (also the director was at this time married to the woman born Ingrid Karlebo, meaning that there were two Ingrid Bergmans on set at times)

But what it mostly means is that Autumn Sonata cannot help but arrive on our doorstep with an extraordinary amount of baggage, the full weight of what the two Bergmans had cultivated as their personae over the years crushing down on the fragile dramatic spine of the movie (Ingmar implied later on that the project was not conceived with Ingrid specifically in mind). The film's narrative is a good one, a small and punishingly honest scrap of interpersonal conflict made out almost entirely of grace notes; but the meta-narrative is such a barnburner that it almost makes it hard to tell. And I would love to at this point segue blithely into a declaration that, well, we will be focused on the film itself, but the reality is that the Dance of the Bergmans makes that impossible - the fundamental gulf between the style of screen acting that Ingrid drew from and the style of screen acting that Ingmar was trying to push her towards actively and deeply colors what the narrative can even be in the first place.

Ingrid Bergman isn't even playing the main character, though, so we probably should put all of that on hold long enough to actually sketch out the fundamentals of what we're dealing with. The heart of the scenario is that Eva (Liv Ullmann) lives a quiet life in the country with her husband Viktor (Halvar Björk), and incredibly boring but stable man, and her sister Helena (Lena Nyman), who has a disability that leaves her with negligible control over her body and a difficulty forming words, such that Eva is the only person with whom she can communicate. Eva also has a mother, Charlotte (Ingrid Bergman), a world-renowned concert pianist, and the emotions she feels towards this imposing figure are all over the place: despondent awe over her talent, desperate desire to be loved by her, unyielding hatred of her for a lifetime of slights, insults, wounds, and outright abuse. Charlotte feels none of this; she has a crucial something Eva lacks, self-confidence, and this is no small part of what has created a chasm between the women.

It's a scenario that's very well-positioned to take advantage of the differences between Ullmann and Ingrid's acting styles. Ullmann, who for the only time in her career with Ingmar (and very possibly the only time in her career, period) isn't dominating the camera simply by sitting in front of it and keep her face steady, is gathering up all of the skills she had honed over her previous eight collaborations with the director to create a work of profound, inward-looking minimalism. Eva is a character whose entire personality is that she cannot get out of her own head, and the interpretation of her relationship with her mother that she has decided upon over years of refining wounds - some of them very real and cruel, some of them perhaps less so - into a vision of Charlotte that's more about the bad feeling she generates than who she is. It's a performance that exists entirely inside the confines of Ullmann's skull, behind the thick, round classes she wars to put an implacable wall between herself and the camera, and Eva is easily the most receding, quiet, inexpressive character the actor has made for any of her films with the director. It's as if Ullmann knew that she wasn't going to be able to pull focus from her co-star, and so didn't even try, instead electing to make this invisibility the core of the character, saving up all her attempts to assert herself as a presence for the few scenes where Eva herself is finally driven to enough frustration that she erupts in her tiny, mousey way. It's a disappointment that in what amounts to the grand finale of her collaboration with Ingmar Bergman (they would reunite 25 years later for Saraband) finds her so thoroughly overshadowed by the project and her co-star, but it's still a stellar piece of acting, making extraordinary use of the close-ups she has been given to let the hurt feelings creep out of her forehead, her eyes, the corner of her mouth.

As for Ingrid Bergman, in her own grand finale (the rest of her career consisted of a stage production of Waters of the Moon in London, and the 1982 television film A Woman Called Golda; this was her last theatrical feature) that's quite a big topic to grapple with indeed. Both Bergmans were too gracious and professional to ever go into details, but it seems, to read around the edges, that it wasn't an especially easy and fun collaboration. Ingmar would later suggest that after a few first couple of days, where he discovered to his horror that Ingrid had worked out every gesture, line reading, and emotional beat without benefit of rehearsing with him or Ullmann, it was all very smooth sailing, but the evidence onscreen would seem to point us in a different direction. Ingrid's performance is very large, even grandiose in ways, with robust physical movement that takes up all available space and loud, declamatory line readings. It's not a bad performance, by any stretch of the imagination - I would in fact suggest that in in the very top tier of any work the actor ever did, at least as good as any of her performances for Hitchcock (Spellbound, Notorious, Under Capricorn - the latter is a bad performance in a bad movie, but anyway) and within a hair's breadth of best performances for Rossellini (Stromboli, Europa '51, Voyage to Italy, Fear), especially as she feeds in something harder and colder later in the performances, something that never gets expressed directly, but glints clearly in her eyes. It's not a performance one expects to see in an Ingmar Bergman movie, is all, and this ends up benefiting Autumn Sonata as much as it harms it.

The harm is that Ingmar clearly wasn't prepared for this, and isn't always very good at recalibrating scenes around Ingrid; for all that the film has been dinged since 1978 as "just another Ingmar Bergman film", the star seems to be in the driver's seat more than the director for much of the running time. This can be exciting, though, because it challenges the norms of his chamber dramas. Because it is just another Bergman film, in its fashion, with the same approach to using close-ups, the same slowness, the same airless quiet in interior rooms where people are too gripped by misery to speak, unless they are speaking in philosophical monologues, that he had refined into a cottage industry over the preceding two decades. This is reductive, and ignores some of the weird things the film is actually doing to distinguish itself (he had never turned his style on a story about an adult child and their parent, for one thing), and anyway "just another Ingmar Bergman film", the year after the bizarre and off-putting The Serpent's Egg, would be more than enough. But adding something like Ingrid's expansive acting style into the world of tight line readings, staticky silence, and shrieks of raw pain that had made up every one of Ingmar's films since Cries and Whispers re-sharpens the edges of that world, making its minimalism feel more purposeful and emotionally draining, less like a reliable shtick.

Which, love the director though I do, there's no denying he had a shtick. But it was a good shtick, one that could yield quite a lot, and it certainly does in Autumn Sonata, which when it's all moving in the same direction is a lacerating portrait of the gulfs between people who feel they ought to love each other and don't, and the way that their angry attempts to do something about that merely end up deepening the gulfs. Ingrid may be taking up all the attention, but it's still fundamentally Ullmann's story, and the way she turns herself into a prism of sorts, refracting her co-stars performance into a way of sketching Eva's inner pain as a system of (non-)reaction shots makes her one of the strongest characters in the director's filmography, in part because of how intensely small and focused on basic humanity this film is; it is intimate in scope even by the standards of Ingmar's earlier chamber films.

There are still efforts to cast this as an intellectual exercise rather than an emotionally-immediate melodrama, though, the most showy of which is the odd framing structure, in which the whole thing is introduced and then summed up by Viktor, directly addressing the camera to create a sense of theatricality that's then immediately punctured by edits and a moving camera, but still puts the film at an odd plane of remove (for that matter, it turns out to be very discordant, in a pretty purposeful way, to usher us into this film that only ever remotely cares about its three women with a man; the film's disinterest in its male characters is so complete that my response to seeing Gunnar Björnstrand, the great Ingmar Bergman collaborator, credited for playing the character of Paul was to wonder who the hell Paul is). It wants us to understand Eva's justified pain while also recognising the places where it isn't justified, but has just become a self-reinforcing desire to be unhappy, and this requires keeping her at a remove; these odd little moments of direct address help do that. And then a climactic exchange of direct address, clearly untethered from any "reality", does exactly the opposite, summing-up the film's interpersonal conflict in expressly emotional terms. Then there is the very striking use of flashbacks, which are unmarked to an unusual degree for this director, simply sweeping into the movie and suddenly creating a subjective experience out of what had been putting such great pains to be objective.

It all makes for a film that's perhaps more difficult to penetrate than it should be, without being nearly difficult enough for that to feel like the "point". Still, as an acting showcase and a story about the divisions within families, it's full of terrific little gestures and beats that all add up to complete portraits of these characters, and the hints of a theme about the terror of aging - implied in the title, stated in the dialogue, and inadvertently reflecting the fact that Ingrid Bergman had received a terminal cancer diagnosis shortly before production started - are gracefully worked onto the rest of the film. And all of it is tied up in possibly Sven Nykvist's most beautiful color cinematography, a lush golden-brown depiction of soft, dusty shadows that wrangles the limitations of '70s film stock into a glowing evocation of the autumn season gestured to in the title, as something both warm and decaying. The film was immediately burdened with a reputation as being a minor work of the director, and even now its reputation falls into a kind of minor-major gap, I think, but even if a lot of the notes are familiar, the way they're being played is so different, so unique to this film, that I can't help but regard this as one of his strongest efforts, a terrific farewell to the theatrical cinematic medium (all of his subsequent projects were made for television) and one of the clear highlights of the offbeat period in his transition to his curious late career.

*As a diehard Greta Garbo partisan, I find this a distressing thing to say, but facts are facts.

But what it mostly means is that Autumn Sonata cannot help but arrive on our doorstep with an extraordinary amount of baggage, the full weight of what the two Bergmans had cultivated as their personae over the years crushing down on the fragile dramatic spine of the movie (Ingmar implied later on that the project was not conceived with Ingrid specifically in mind). The film's narrative is a good one, a small and punishingly honest scrap of interpersonal conflict made out almost entirely of grace notes; but the meta-narrative is such a barnburner that it almost makes it hard to tell. And I would love to at this point segue blithely into a declaration that, well, we will be focused on the film itself, but the reality is that the Dance of the Bergmans makes that impossible - the fundamental gulf between the style of screen acting that Ingrid drew from and the style of screen acting that Ingmar was trying to push her towards actively and deeply colors what the narrative can even be in the first place.

Ingrid Bergman isn't even playing the main character, though, so we probably should put all of that on hold long enough to actually sketch out the fundamentals of what we're dealing with. The heart of the scenario is that Eva (Liv Ullmann) lives a quiet life in the country with her husband Viktor (Halvar Björk), and incredibly boring but stable man, and her sister Helena (Lena Nyman), who has a disability that leaves her with negligible control over her body and a difficulty forming words, such that Eva is the only person with whom she can communicate. Eva also has a mother, Charlotte (Ingrid Bergman), a world-renowned concert pianist, and the emotions she feels towards this imposing figure are all over the place: despondent awe over her talent, desperate desire to be loved by her, unyielding hatred of her for a lifetime of slights, insults, wounds, and outright abuse. Charlotte feels none of this; she has a crucial something Eva lacks, self-confidence, and this is no small part of what has created a chasm between the women.

It's a scenario that's very well-positioned to take advantage of the differences between Ullmann and Ingrid's acting styles. Ullmann, who for the only time in her career with Ingmar (and very possibly the only time in her career, period) isn't dominating the camera simply by sitting in front of it and keep her face steady, is gathering up all of the skills she had honed over her previous eight collaborations with the director to create a work of profound, inward-looking minimalism. Eva is a character whose entire personality is that she cannot get out of her own head, and the interpretation of her relationship with her mother that she has decided upon over years of refining wounds - some of them very real and cruel, some of them perhaps less so - into a vision of Charlotte that's more about the bad feeling she generates than who she is. It's a performance that exists entirely inside the confines of Ullmann's skull, behind the thick, round classes she wars to put an implacable wall between herself and the camera, and Eva is easily the most receding, quiet, inexpressive character the actor has made for any of her films with the director. It's as if Ullmann knew that she wasn't going to be able to pull focus from her co-star, and so didn't even try, instead electing to make this invisibility the core of the character, saving up all her attempts to assert herself as a presence for the few scenes where Eva herself is finally driven to enough frustration that she erupts in her tiny, mousey way. It's a disappointment that in what amounts to the grand finale of her collaboration with Ingmar Bergman (they would reunite 25 years later for Saraband) finds her so thoroughly overshadowed by the project and her co-star, but it's still a stellar piece of acting, making extraordinary use of the close-ups she has been given to let the hurt feelings creep out of her forehead, her eyes, the corner of her mouth.

As for Ingrid Bergman, in her own grand finale (the rest of her career consisted of a stage production of Waters of the Moon in London, and the 1982 television film A Woman Called Golda; this was her last theatrical feature) that's quite a big topic to grapple with indeed. Both Bergmans were too gracious and professional to ever go into details, but it seems, to read around the edges, that it wasn't an especially easy and fun collaboration. Ingmar would later suggest that after a few first couple of days, where he discovered to his horror that Ingrid had worked out every gesture, line reading, and emotional beat without benefit of rehearsing with him or Ullmann, it was all very smooth sailing, but the evidence onscreen would seem to point us in a different direction. Ingrid's performance is very large, even grandiose in ways, with robust physical movement that takes up all available space and loud, declamatory line readings. It's not a bad performance, by any stretch of the imagination - I would in fact suggest that in in the very top tier of any work the actor ever did, at least as good as any of her performances for Hitchcock (Spellbound, Notorious, Under Capricorn - the latter is a bad performance in a bad movie, but anyway) and within a hair's breadth of best performances for Rossellini (Stromboli, Europa '51, Voyage to Italy, Fear), especially as she feeds in something harder and colder later in the performances, something that never gets expressed directly, but glints clearly in her eyes. It's not a performance one expects to see in an Ingmar Bergman movie, is all, and this ends up benefiting Autumn Sonata as much as it harms it.

The harm is that Ingmar clearly wasn't prepared for this, and isn't always very good at recalibrating scenes around Ingrid; for all that the film has been dinged since 1978 as "just another Ingmar Bergman film", the star seems to be in the driver's seat more than the director for much of the running time. This can be exciting, though, because it challenges the norms of his chamber dramas. Because it is just another Bergman film, in its fashion, with the same approach to using close-ups, the same slowness, the same airless quiet in interior rooms where people are too gripped by misery to speak, unless they are speaking in philosophical monologues, that he had refined into a cottage industry over the preceding two decades. This is reductive, and ignores some of the weird things the film is actually doing to distinguish itself (he had never turned his style on a story about an adult child and their parent, for one thing), and anyway "just another Ingmar Bergman film", the year after the bizarre and off-putting The Serpent's Egg, would be more than enough. But adding something like Ingrid's expansive acting style into the world of tight line readings, staticky silence, and shrieks of raw pain that had made up every one of Ingmar's films since Cries and Whispers re-sharpens the edges of that world, making its minimalism feel more purposeful and emotionally draining, less like a reliable shtick.

Which, love the director though I do, there's no denying he had a shtick. But it was a good shtick, one that could yield quite a lot, and it certainly does in Autumn Sonata, which when it's all moving in the same direction is a lacerating portrait of the gulfs between people who feel they ought to love each other and don't, and the way that their angry attempts to do something about that merely end up deepening the gulfs. Ingrid may be taking up all the attention, but it's still fundamentally Ullmann's story, and the way she turns herself into a prism of sorts, refracting her co-stars performance into a way of sketching Eva's inner pain as a system of (non-)reaction shots makes her one of the strongest characters in the director's filmography, in part because of how intensely small and focused on basic humanity this film is; it is intimate in scope even by the standards of Ingmar's earlier chamber films.

There are still efforts to cast this as an intellectual exercise rather than an emotionally-immediate melodrama, though, the most showy of which is the odd framing structure, in which the whole thing is introduced and then summed up by Viktor, directly addressing the camera to create a sense of theatricality that's then immediately punctured by edits and a moving camera, but still puts the film at an odd plane of remove (for that matter, it turns out to be very discordant, in a pretty purposeful way, to usher us into this film that only ever remotely cares about its three women with a man; the film's disinterest in its male characters is so complete that my response to seeing Gunnar Björnstrand, the great Ingmar Bergman collaborator, credited for playing the character of Paul was to wonder who the hell Paul is). It wants us to understand Eva's justified pain while also recognising the places where it isn't justified, but has just become a self-reinforcing desire to be unhappy, and this requires keeping her at a remove; these odd little moments of direct address help do that. And then a climactic exchange of direct address, clearly untethered from any "reality", does exactly the opposite, summing-up the film's interpersonal conflict in expressly emotional terms. Then there is the very striking use of flashbacks, which are unmarked to an unusual degree for this director, simply sweeping into the movie and suddenly creating a subjective experience out of what had been putting such great pains to be objective.

It all makes for a film that's perhaps more difficult to penetrate than it should be, without being nearly difficult enough for that to feel like the "point". Still, as an acting showcase and a story about the divisions within families, it's full of terrific little gestures and beats that all add up to complete portraits of these characters, and the hints of a theme about the terror of aging - implied in the title, stated in the dialogue, and inadvertently reflecting the fact that Ingrid Bergman had received a terminal cancer diagnosis shortly before production started - are gracefully worked onto the rest of the film. And all of it is tied up in possibly Sven Nykvist's most beautiful color cinematography, a lush golden-brown depiction of soft, dusty shadows that wrangles the limitations of '70s film stock into a glowing evocation of the autumn season gestured to in the title, as something both warm and decaying. The film was immediately burdened with a reputation as being a minor work of the director, and even now its reputation falls into a kind of minor-major gap, I think, but even if a lot of the notes are familiar, the way they're being played is so different, so unique to this film, that I can't help but regard this as one of his strongest efforts, a terrific farewell to the theatrical cinematic medium (all of his subsequent projects were made for television) and one of the clear highlights of the offbeat period in his transition to his curious late career.

*As a diehard Greta Garbo partisan, I find this a distressing thing to say, but facts are facts.