Ya got Troubles

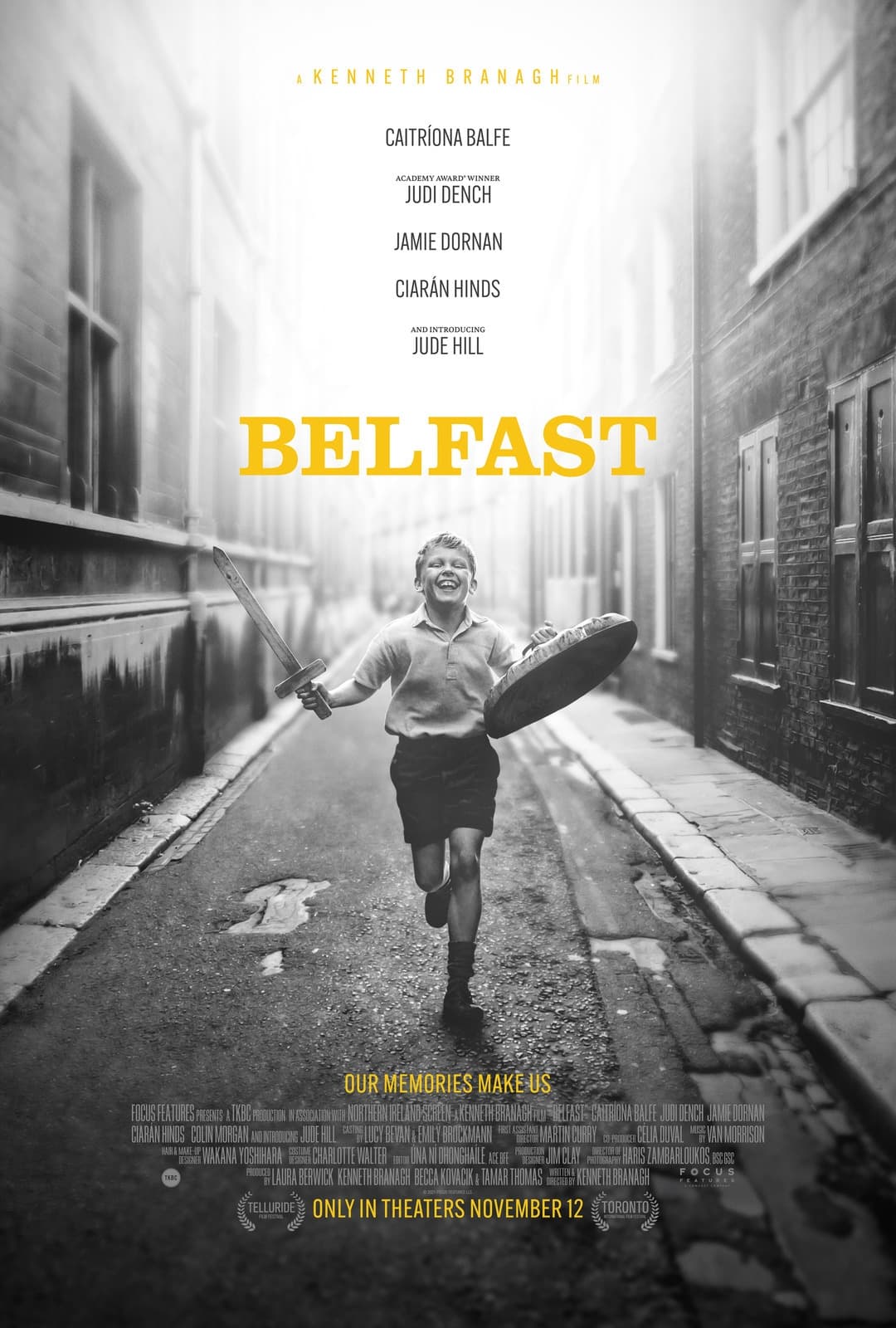

The idea of Kenneth Branagh writing and directing a semi-autobiographical story of his childhood in Belfast, right around the time that tensions between the nationalists and loyalists in Northern Ireland broke out into open violence in 1969, is not one that fills me with any great amount of automatic optimism. Branagh is quite a sufficiently self-obsessed artist as it is, without actually mining his own life for drama, and I do not tend to be very enthusiastic about his filmmaking under any circumstances. So color me quite dazzled that Belfast, to give the film its monumental title, is more or less perfectly fine. Certainly, Branagh makes sure you never forget it was Directed! by an Artist!, and the pileup of very self-consciously framed shots gets a bit exhausting by the end, even with the film coming in at a very agreeable 98 minutes. But despite this, the film doesn't really feel fussy or overly self-serious; just a kaleidoscopic view of about seven months in the life Buddy (Jude Hill), the film's nine-year-old Branagh analogue (Branalogue?), from August 15, 1969 (the week that more or less kicked off 30 years of violent conflict in Northern Ireland, the Troubles) until shortly before Easter, 1970.

There's a narrative spine here, basically the same one that happened to Branagh when he was himself a nine-year-old in Belfast in 1969. Buddy's dad (Jamie Dornan) works in England, not far outside of London, and he comes back most weekends to make sure the family is doing well in his absence; this makes him a target for some fellow Ulster Protestants who think he's not concerned doing enough to secure the well-being of the community, which in their view means "terrorizing Catholics and destroying their homes and property". This is all enough for Pa to think that it's high time for the family to get the hell out before the city becomes too dangerous to raise kids in, but his wife, Buddy's mom (Catríona Balfe) is concerned that their roots are set too deep in Belfast, including the centering presence of Pa's own parents (Ciarán Hinds and Judi Dench - and how brave of Branagh to cast his dear friend Judi in another role that would require her to put on an Irish accent, so soon after after the hate crime of her performance in their last collaboration, 2020's Artemis Fowl), for them to survive a transplant to England, particular given how much the residents of that country have historically cared for the Irish.

Belfast isn't really "about" that domestic conflict, though; that's mostly the background to scene after scene of Buddy wandering around a fairly small chunk of the city. The thing that the movie is best at is the capturing the unthinking egotism of childhood, fixating on things like schoolroom crushes and impressing the popular older kids as being every bit as consequential and important as the rioting and ever-present threat of violence and constant alarmist news reports on the television. I almost wonder if Branagh arrives there by accident; Belfast has a very weird visual style that doesn't seem to be at all about point-of-view or any other sort of storytelling, though there are individual shots that are anchored by Buddy sitting on the far edges of adult conversations, which at least give the impression that this is about an uncomprehending, innocent voyeur trying to make sense of a grown-up world that seems very urgent without ever trying to explain itself to him.

Mostly, though, it just feels like the whole movie consists of shots that are complicated and striking, often involving very complicated staging in depth. Sometimes this is effective, as in a conversation between Buddy and his grandfather in the alley behind the grandparents' house, while Granny's head floats, almost invisibly, in a window at the back of the alley, a tiny rectangle of black. Sometimes, it doesn't seem to do a damn thing at all, just show off the Branagh has put some thought into what might be involved mechanically in shooting a Wyler-esque or Wellesian film of long takes in deep space, but not why you would make the choice to film a movie that way. It may be uncharitable to say that the film is basically just a Roma knock-off, but Belfast doesn't do anything to stave off that comparison; the main difference is that Alfonso Cuarón had a clear strategy in mind for why he wanted his own shimmering black-and-white plunge in his childhood memories to take the form of slow-moving tableaux, and Branagh apparently doesn't. He doesn't even seem to realise that he is shooting a slow-moving long-take picture, given his willingness to randomly interrupt shots that obviously want to be left uncut with inserts; I am chiefly thinking of a moment when Buddy's grandparents are dancing towards the end, when a scene built around three static wide shots is inexplicably fragmented by plugging the first wide shot back into the middle of the second, just so we can confirm that Buddy is still there.

But anyway, the film ends up having no obvious visual strategy, no throughline; it's just a lot of images, some of them very "cool", just hanging out. And this somehow does help with that feeling of watching this through Buddy's uncomprehending eyes: the film itself doesn't seem to have a sense of how to mark out key moments, and so everything is just part of a free flow of big and small moments, all jumbled up indiscriminately. And - again, I suspect by accident - that ends up fitting nicely with the sense of a young boy who himself can't discriminate between large and small moments.

It helps considerably that the film is gorgeous: Branagh's usual cinematographer, Haris Zambarloukos, has never been better than he is here, working with high-contrast black and white that creates sharp, precise depictions of the film's environments as textured, living spaces. It's a bit of a straightforward play to use black-and-white to evoke the distant past, and it leads to a corny, mostly unsuccessful motif of Buddy seeing movies and live theater in full color (the implication being that the performing arts are "more real", or "more vital"? That suggests a more shlockily romantic film than we seem to be getting, but I guess it's possible). Still, the execution is so good that it's hard to complain.

The actual family story being told through all of this is kind of peculiarly vague; it's hard to say if Branagh actually has feelings about re-eneacting his childhood, or if he thinks of his parents and grandparents are especially specific people. The actors are good enough at bringing sloppy life to their parts that it somewhat obscures it, but the screenplay is very surface-level in how it sketches out people. This goes hand-in-hand with its refusal to over-explain or slow things down to give us unnecessary context, so it's sort of a mixture of the good and the bad; maybe it's even meant to evoke how Buddy can't really bring himself to think of his adult relatives as people with actual inner lives. Still, it feels curiously inert, emotionally, for something that's presumably coming direct from the writer-director's heart. He seems to care more about Belfast itself than about any of the people in it (leading to an absolutely deadening opening montage, showing the city today in full color - it feels like nothing so much as a tourism board-style "Look, the city isn't ravaged by civil war any longer" gesture that does nothing for the rest of the movie), and that's not a terrible approach, especially given the way the script proceeds as a series of moments rather than a single flow of drama and history. But it's not really enough of an art movie to make that work; it's ultimately a sweet-natured domestic drama and character study. A hollow one, seemingly by design. Still, it moves fast, it's pretty, and it's awfully watchable, so it's hard to feel especially grumpy about its shortcomings, even as I can't imagine feeling actually excited about its strengths.

There's a narrative spine here, basically the same one that happened to Branagh when he was himself a nine-year-old in Belfast in 1969. Buddy's dad (Jamie Dornan) works in England, not far outside of London, and he comes back most weekends to make sure the family is doing well in his absence; this makes him a target for some fellow Ulster Protestants who think he's not concerned doing enough to secure the well-being of the community, which in their view means "terrorizing Catholics and destroying their homes and property". This is all enough for Pa to think that it's high time for the family to get the hell out before the city becomes too dangerous to raise kids in, but his wife, Buddy's mom (Catríona Balfe) is concerned that their roots are set too deep in Belfast, including the centering presence of Pa's own parents (Ciarán Hinds and Judi Dench - and how brave of Branagh to cast his dear friend Judi in another role that would require her to put on an Irish accent, so soon after after the hate crime of her performance in their last collaboration, 2020's Artemis Fowl), for them to survive a transplant to England, particular given how much the residents of that country have historically cared for the Irish.

Belfast isn't really "about" that domestic conflict, though; that's mostly the background to scene after scene of Buddy wandering around a fairly small chunk of the city. The thing that the movie is best at is the capturing the unthinking egotism of childhood, fixating on things like schoolroom crushes and impressing the popular older kids as being every bit as consequential and important as the rioting and ever-present threat of violence and constant alarmist news reports on the television. I almost wonder if Branagh arrives there by accident; Belfast has a very weird visual style that doesn't seem to be at all about point-of-view or any other sort of storytelling, though there are individual shots that are anchored by Buddy sitting on the far edges of adult conversations, which at least give the impression that this is about an uncomprehending, innocent voyeur trying to make sense of a grown-up world that seems very urgent without ever trying to explain itself to him.

Mostly, though, it just feels like the whole movie consists of shots that are complicated and striking, often involving very complicated staging in depth. Sometimes this is effective, as in a conversation between Buddy and his grandfather in the alley behind the grandparents' house, while Granny's head floats, almost invisibly, in a window at the back of the alley, a tiny rectangle of black. Sometimes, it doesn't seem to do a damn thing at all, just show off the Branagh has put some thought into what might be involved mechanically in shooting a Wyler-esque or Wellesian film of long takes in deep space, but not why you would make the choice to film a movie that way. It may be uncharitable to say that the film is basically just a Roma knock-off, but Belfast doesn't do anything to stave off that comparison; the main difference is that Alfonso Cuarón had a clear strategy in mind for why he wanted his own shimmering black-and-white plunge in his childhood memories to take the form of slow-moving tableaux, and Branagh apparently doesn't. He doesn't even seem to realise that he is shooting a slow-moving long-take picture, given his willingness to randomly interrupt shots that obviously want to be left uncut with inserts; I am chiefly thinking of a moment when Buddy's grandparents are dancing towards the end, when a scene built around three static wide shots is inexplicably fragmented by plugging the first wide shot back into the middle of the second, just so we can confirm that Buddy is still there.

But anyway, the film ends up having no obvious visual strategy, no throughline; it's just a lot of images, some of them very "cool", just hanging out. And this somehow does help with that feeling of watching this through Buddy's uncomprehending eyes: the film itself doesn't seem to have a sense of how to mark out key moments, and so everything is just part of a free flow of big and small moments, all jumbled up indiscriminately. And - again, I suspect by accident - that ends up fitting nicely with the sense of a young boy who himself can't discriminate between large and small moments.

It helps considerably that the film is gorgeous: Branagh's usual cinematographer, Haris Zambarloukos, has never been better than he is here, working with high-contrast black and white that creates sharp, precise depictions of the film's environments as textured, living spaces. It's a bit of a straightforward play to use black-and-white to evoke the distant past, and it leads to a corny, mostly unsuccessful motif of Buddy seeing movies and live theater in full color (the implication being that the performing arts are "more real", or "more vital"? That suggests a more shlockily romantic film than we seem to be getting, but I guess it's possible). Still, the execution is so good that it's hard to complain.

The actual family story being told through all of this is kind of peculiarly vague; it's hard to say if Branagh actually has feelings about re-eneacting his childhood, or if he thinks of his parents and grandparents are especially specific people. The actors are good enough at bringing sloppy life to their parts that it somewhat obscures it, but the screenplay is very surface-level in how it sketches out people. This goes hand-in-hand with its refusal to over-explain or slow things down to give us unnecessary context, so it's sort of a mixture of the good and the bad; maybe it's even meant to evoke how Buddy can't really bring himself to think of his adult relatives as people with actual inner lives. Still, it feels curiously inert, emotionally, for something that's presumably coming direct from the writer-director's heart. He seems to care more about Belfast itself than about any of the people in it (leading to an absolutely deadening opening montage, showing the city today in full color - it feels like nothing so much as a tourism board-style "Look, the city isn't ravaged by civil war any longer" gesture that does nothing for the rest of the movie), and that's not a terrible approach, especially given the way the script proceeds as a series of moments rather than a single flow of drama and history. But it's not really enough of an art movie to make that work; it's ultimately a sweet-natured domestic drama and character study. A hollow one, seemingly by design. Still, it moves fast, it's pretty, and it's awfully watchable, so it's hard to feel especially grumpy about its shortcomings, even as I can't imagine feeling actually excited about its strengths.