The man without a face

A review requested by Travis, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Two decades into the 21st Century, the phrase "a Sam Raimi superhero movie" surely takes us straight to 2002's Spider-Man and its two sequels, and this is just. These are, after all, still pretty much the high-water mark for the entire genre (two of them are, at least), and would be the crown jewels of many a fine and admirable directorial career. I'm not sure, however, that they're the crown jewels of Sam Raimi's career. They are popcorn blockbusters, massive studio tentpoles in a filmography dominated by scrappy termite art made on the outside edges of the film industry. Raimi films are nasty little buggers, enthusiastic about their warped worldview and grotesque comedy. There's a little of that in Spider-Man, and I would not suggest that any other director would have made that film the way Raimi made it, nor as well, but he's still playing nice with Columbia's money.

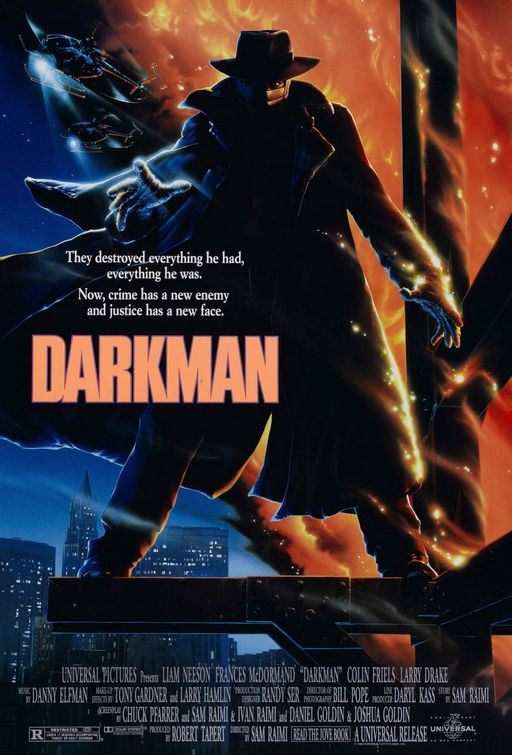

Therfore, for a proper example of a Sam Raimi superhero movie, we need to go twelve years further back, to the director's fourth feature, and the first one he made for a major studio: 1990's Darkman. 1990 was a curious year for superhero movies: it was a year after Tim Burtor (another indie weirdo with a distinctively warped aesthetic worldview) made the enormous hit Batman for Warner Bros., and everybody knew in advance it was going to be an enormous hit, so a few different studios had projects lined up and ready to go for the following summer, but none of them were actually made with the benefit of knowing what Batman was actually going to beget, or what about it audiences would respond to. Darkman, for example was already in development at Universal by the end of 1987, so any resemblances to Batman are surely coincidental, though it is awfully reminiscent of that film. Admittedly, that probably has more to do with Danny Elfman's score than anything; there are more affinities between the two film's music than simply sharing a single composer. This is true even though Darkman goes in a much more florid, operatic, melodramatic direction that gets at more of the gothic morbidity Elfman typically provided in his Burton soundtracks but held back from in Batman somewhat. But I am wandering away from my point.

Darkman was Raimi's original idea for a new superhero, and given the director's penchant for bending genres around, it's no particular surprise that the ideas take us much closer to horror than the likes of Batman or the Shadow (the two properties Raimi wanted to adapt, but were snapped up by other directors before he got to them). The story he wrote - which took the combined efforts of five credited writers to transform into a screenplay, Raimi among them - basically asks the question, "what if the Phantom of the Opera became Batman?", centering around experimental biochemist Peyton Westlake (Liam Neeson), burned almost to death in a mob-related attack intended to put a little fear into his crusading lawyer girlfriend, Julie Hastings (Frances McDormand, working with her personal friend Raimi for the only time, outside of a cameo). After his mangled body was assumed to be that of a vagrant, he ended up receiving a highly experimental treatment that kept him alive and left him incapable of feeling the excruciating pain he'd otherwise be in, but left him unable to process the feeling of touch at all. In a scene the movie pushes through fast enough that we're not invited to notice how extravagantly dumb it is, the doctor responsible observes that this means he'll feel emotions much more intensely as well as have much more strength, since his body is basically going to be pumping adrenaline constantly to compensate for his lost feelings. So basically, a super-strong emo kid with hideous scars all over his face, and since the project Peyton was working on at the time of the attack was a synthetic skin replacement for burn victims, that's less of a problem than it might be. Unfortunately, the skin is highly sensitive to light, and after 99 minutes, destabilises in a bubbling boil of body horror that's one of several ways in which Darkman cheerfully earns its R-rating.

That whole origin story is a bundle of clichés, and Raimi and Darkman know it; the whole film has a tongue-in-cheek energy to go along with its dark cinematography by Bill Bope. This comes in through the usual Raimi ways: tracking shots where the camera swoops forward at high speed (though never, in this film, at a level just a couple of feet about the ground, more's the pity), heightened violence that splits the difference between upsetting and ridiculous in just the right way. For example, the main villain, a crime boss named Durant (Larry Drake) is introduced in the film's first scene, massacring the competition, and when the only person left is opposing crime boss Eddie Black (Jessie Lawrence Ferguson), Durant whips out a cigar cutter and starts chopping the other man's fingers off. This is upsetting. He makes a menacing joke in a goofy voice that throws us into the opening credits. This is upsetting but also kind of funny. And then later, we see Durant with a case of the fingers he has cut off enemies, fussily scrubbing one with a Q-tip, like an obsessive baseball card collector on the hunt for any errant fingerprints. This is downright hilarious. The balance of "I don't know if I should vomit or laugh" feels like it's the quintessential element of Sam Raimi's filmography, but in reality, he sort of only ever really did it in this film's immediate predecessor, Evil Dead II; I'd say that Darkman is probably the first runner-up in successfully executing the impossible mixture of tones, genres and attitudes that marks out the director's most characteristic work.

In this case, it's less because the film is a horror-comedy, though you could with justification use both of those words to describe it; in this case, it's because of the campy quality lying directly below how extremely seriously the film appears to take its subject matter. Twice, Peyton hears something that makes him so intensely angry that the world is suddenly replaced with a cheesy video effect, and yes, the cheesiness is undeniable - but at the same time, there's no sense that the film is mocking the humiliated rage he's feeling at those point. Elfman's score digs deep into a lot of very corny tricks from the annals of classical horror in creating a robust, creaky sense of sweeping melodramatic grandeur, but there aren't exactly jokes in the music, just a good sense of genre history. And that goes with how much this Universal production ends up feeling like a classic Universal horror picture in a lot of ways, with the shadowy lighting of mad science labs and whatnot. Peyton's bandaged face isn't just drawing from The Invisible Man of 1933 - I detect more than a little of the Hammer Phantom of the Opera with Herbert Lom, from 1962, for starters - but it's an unmistakable influence. Even the studio logo at the start sort of cues this in that direction: it's an accident and nothing but that this came out during Universal's 75th anniversary, the year that the studio logo consisted of a montage of earlier logos, but anyone who can see that old biplane flying its rickety path around the spinning globe in front of this film of all films and not feel the kinship with those old monster movies of the '30s lacks romance in their heart.

So it's a bit of disgusting contemporary body horror, a bit of classic horror atmosphere, and it has a pretty obvious sense of sarcastic humor about all of the above, and on top of everything, it is a superhero action thriller. That all of this fits together consistently throughout the film's length is a bit of a miracle, and owes a lot to Raimi's unique skill at making us laugh at things we should still take seriously. But it also owes a lot to the serendipitous casting of Neeson, who was nobody's first choice for the role, and didn't have the sort of filmography that would especially suggest he'd be a good fit for this. Frankly, I'm not sure that he has since established that kind of filmography, but he's an uncannily perfect fit for the role regardless: the role as conceived requires combining a sympathetic sense of tragedy and loss while showing a steady increase in murderous rage as his overtaxed emotions get more and more excessive, and he can't be afraid of seeming goofy while doing any of it. Plus he spends a lot of the film in latex. Neeson hits a note of melancholic camp early on and manages to vary it throughout the film; he and McDormand also have some of the best chemistry of their entire careers with each other, something easygoing and quotidian but still flirty and cute, and this adds a nice human center to a film that probably doesn't need such a thing, though it's no harm for it to have it.

Having some kind of character truth anchoring it also lets the film avoid seeming ludicrous. Darkman gets the iconic pomposity of superheroes, and enjoys playing with it, so there's quite a lot of self-conscious stateliness to how Neeson is posed within shots, like they were modeled after non-existent splash pages. It likes the idea of seeming mythic, plainly, and of having Neeson growl out florid lines whose natural home is in a dialogue bubble. At the same time, it never pretends that the stakes are all that high, or that this is actually mythic, rather than just larger-than-life popcorn movie theatricality, and again, there's barely anything in the entire film that's definitely not a joke of some kind. But there's just enough real feeling underneath it that it never threatens to blow away, either. It's a pretty delicate balancing act, all told, maybe even Raimi's most carefully controlled movie - I prefer the gonzo lunacy of an Evil Dead II or a Drag Me to Hell, to be sure, but this is still wholly delightful and admirable grave nonsense, and I wouldn't feel at all wrong about putting it in the company of those two most splendid examples of Raimi being Raimi.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Two decades into the 21st Century, the phrase "a Sam Raimi superhero movie" surely takes us straight to 2002's Spider-Man and its two sequels, and this is just. These are, after all, still pretty much the high-water mark for the entire genre (two of them are, at least), and would be the crown jewels of many a fine and admirable directorial career. I'm not sure, however, that they're the crown jewels of Sam Raimi's career. They are popcorn blockbusters, massive studio tentpoles in a filmography dominated by scrappy termite art made on the outside edges of the film industry. Raimi films are nasty little buggers, enthusiastic about their warped worldview and grotesque comedy. There's a little of that in Spider-Man, and I would not suggest that any other director would have made that film the way Raimi made it, nor as well, but he's still playing nice with Columbia's money.

Therfore, for a proper example of a Sam Raimi superhero movie, we need to go twelve years further back, to the director's fourth feature, and the first one he made for a major studio: 1990's Darkman. 1990 was a curious year for superhero movies: it was a year after Tim Burtor (another indie weirdo with a distinctively warped aesthetic worldview) made the enormous hit Batman for Warner Bros., and everybody knew in advance it was going to be an enormous hit, so a few different studios had projects lined up and ready to go for the following summer, but none of them were actually made with the benefit of knowing what Batman was actually going to beget, or what about it audiences would respond to. Darkman, for example was already in development at Universal by the end of 1987, so any resemblances to Batman are surely coincidental, though it is awfully reminiscent of that film. Admittedly, that probably has more to do with Danny Elfman's score than anything; there are more affinities between the two film's music than simply sharing a single composer. This is true even though Darkman goes in a much more florid, operatic, melodramatic direction that gets at more of the gothic morbidity Elfman typically provided in his Burton soundtracks but held back from in Batman somewhat. But I am wandering away from my point.

Darkman was Raimi's original idea for a new superhero, and given the director's penchant for bending genres around, it's no particular surprise that the ideas take us much closer to horror than the likes of Batman or the Shadow (the two properties Raimi wanted to adapt, but were snapped up by other directors before he got to them). The story he wrote - which took the combined efforts of five credited writers to transform into a screenplay, Raimi among them - basically asks the question, "what if the Phantom of the Opera became Batman?", centering around experimental biochemist Peyton Westlake (Liam Neeson), burned almost to death in a mob-related attack intended to put a little fear into his crusading lawyer girlfriend, Julie Hastings (Frances McDormand, working with her personal friend Raimi for the only time, outside of a cameo). After his mangled body was assumed to be that of a vagrant, he ended up receiving a highly experimental treatment that kept him alive and left him incapable of feeling the excruciating pain he'd otherwise be in, but left him unable to process the feeling of touch at all. In a scene the movie pushes through fast enough that we're not invited to notice how extravagantly dumb it is, the doctor responsible observes that this means he'll feel emotions much more intensely as well as have much more strength, since his body is basically going to be pumping adrenaline constantly to compensate for his lost feelings. So basically, a super-strong emo kid with hideous scars all over his face, and since the project Peyton was working on at the time of the attack was a synthetic skin replacement for burn victims, that's less of a problem than it might be. Unfortunately, the skin is highly sensitive to light, and after 99 minutes, destabilises in a bubbling boil of body horror that's one of several ways in which Darkman cheerfully earns its R-rating.

That whole origin story is a bundle of clichés, and Raimi and Darkman know it; the whole film has a tongue-in-cheek energy to go along with its dark cinematography by Bill Bope. This comes in through the usual Raimi ways: tracking shots where the camera swoops forward at high speed (though never, in this film, at a level just a couple of feet about the ground, more's the pity), heightened violence that splits the difference between upsetting and ridiculous in just the right way. For example, the main villain, a crime boss named Durant (Larry Drake) is introduced in the film's first scene, massacring the competition, and when the only person left is opposing crime boss Eddie Black (Jessie Lawrence Ferguson), Durant whips out a cigar cutter and starts chopping the other man's fingers off. This is upsetting. He makes a menacing joke in a goofy voice that throws us into the opening credits. This is upsetting but also kind of funny. And then later, we see Durant with a case of the fingers he has cut off enemies, fussily scrubbing one with a Q-tip, like an obsessive baseball card collector on the hunt for any errant fingerprints. This is downright hilarious. The balance of "I don't know if I should vomit or laugh" feels like it's the quintessential element of Sam Raimi's filmography, but in reality, he sort of only ever really did it in this film's immediate predecessor, Evil Dead II; I'd say that Darkman is probably the first runner-up in successfully executing the impossible mixture of tones, genres and attitudes that marks out the director's most characteristic work.

In this case, it's less because the film is a horror-comedy, though you could with justification use both of those words to describe it; in this case, it's because of the campy quality lying directly below how extremely seriously the film appears to take its subject matter. Twice, Peyton hears something that makes him so intensely angry that the world is suddenly replaced with a cheesy video effect, and yes, the cheesiness is undeniable - but at the same time, there's no sense that the film is mocking the humiliated rage he's feeling at those point. Elfman's score digs deep into a lot of very corny tricks from the annals of classical horror in creating a robust, creaky sense of sweeping melodramatic grandeur, but there aren't exactly jokes in the music, just a good sense of genre history. And that goes with how much this Universal production ends up feeling like a classic Universal horror picture in a lot of ways, with the shadowy lighting of mad science labs and whatnot. Peyton's bandaged face isn't just drawing from The Invisible Man of 1933 - I detect more than a little of the Hammer Phantom of the Opera with Herbert Lom, from 1962, for starters - but it's an unmistakable influence. Even the studio logo at the start sort of cues this in that direction: it's an accident and nothing but that this came out during Universal's 75th anniversary, the year that the studio logo consisted of a montage of earlier logos, but anyone who can see that old biplane flying its rickety path around the spinning globe in front of this film of all films and not feel the kinship with those old monster movies of the '30s lacks romance in their heart.

So it's a bit of disgusting contemporary body horror, a bit of classic horror atmosphere, and it has a pretty obvious sense of sarcastic humor about all of the above, and on top of everything, it is a superhero action thriller. That all of this fits together consistently throughout the film's length is a bit of a miracle, and owes a lot to Raimi's unique skill at making us laugh at things we should still take seriously. But it also owes a lot to the serendipitous casting of Neeson, who was nobody's first choice for the role, and didn't have the sort of filmography that would especially suggest he'd be a good fit for this. Frankly, I'm not sure that he has since established that kind of filmography, but he's an uncannily perfect fit for the role regardless: the role as conceived requires combining a sympathetic sense of tragedy and loss while showing a steady increase in murderous rage as his overtaxed emotions get more and more excessive, and he can't be afraid of seeming goofy while doing any of it. Plus he spends a lot of the film in latex. Neeson hits a note of melancholic camp early on and manages to vary it throughout the film; he and McDormand also have some of the best chemistry of their entire careers with each other, something easygoing and quotidian but still flirty and cute, and this adds a nice human center to a film that probably doesn't need such a thing, though it's no harm for it to have it.

Having some kind of character truth anchoring it also lets the film avoid seeming ludicrous. Darkman gets the iconic pomposity of superheroes, and enjoys playing with it, so there's quite a lot of self-conscious stateliness to how Neeson is posed within shots, like they were modeled after non-existent splash pages. It likes the idea of seeming mythic, plainly, and of having Neeson growl out florid lines whose natural home is in a dialogue bubble. At the same time, it never pretends that the stakes are all that high, or that this is actually mythic, rather than just larger-than-life popcorn movie theatricality, and again, there's barely anything in the entire film that's definitely not a joke of some kind. But there's just enough real feeling underneath it that it never threatens to blow away, either. It's a pretty delicate balancing act, all told, maybe even Raimi's most carefully controlled movie - I prefer the gonzo lunacy of an Evil Dead II or a Drag Me to Hell, to be sure, but this is still wholly delightful and admirable grave nonsense, and I wouldn't feel at all wrong about putting it in the company of those two most splendid examples of Raimi being Raimi.