One last rodeo

Clint Eastwood, all 91 years of him, has been at the "what if this is his very last film?" stage of his directorial career at least since 2008's Gran Torino, ten whole movies ago. That was also the first of his "well, even if he keeps directing, you can definitely tell that he's retiring from acting, anyway" phase, as well, which has only added two more films since then: 2012's Trouble with the Curve (which he didn't direct) and 2018's The Mule. All of which is to say that the director-star's newest, Cry Macho sure as hell seems like a movie you would make if you, Clint Eastwood, knew that you this was the end of your 66 years in front of the camera, going all the way back to 1955's Revenge of the Creature, and also you, Clint Eastwood, wanted to this to be the final statement you would ever make on the themes and motifs that have defined your half century as director, reaching back to 1971's Play Misty for Me. And, I mean, the dude is 91, one of these has to be his last film, whether he is very obviously presenting it in those terms or not.

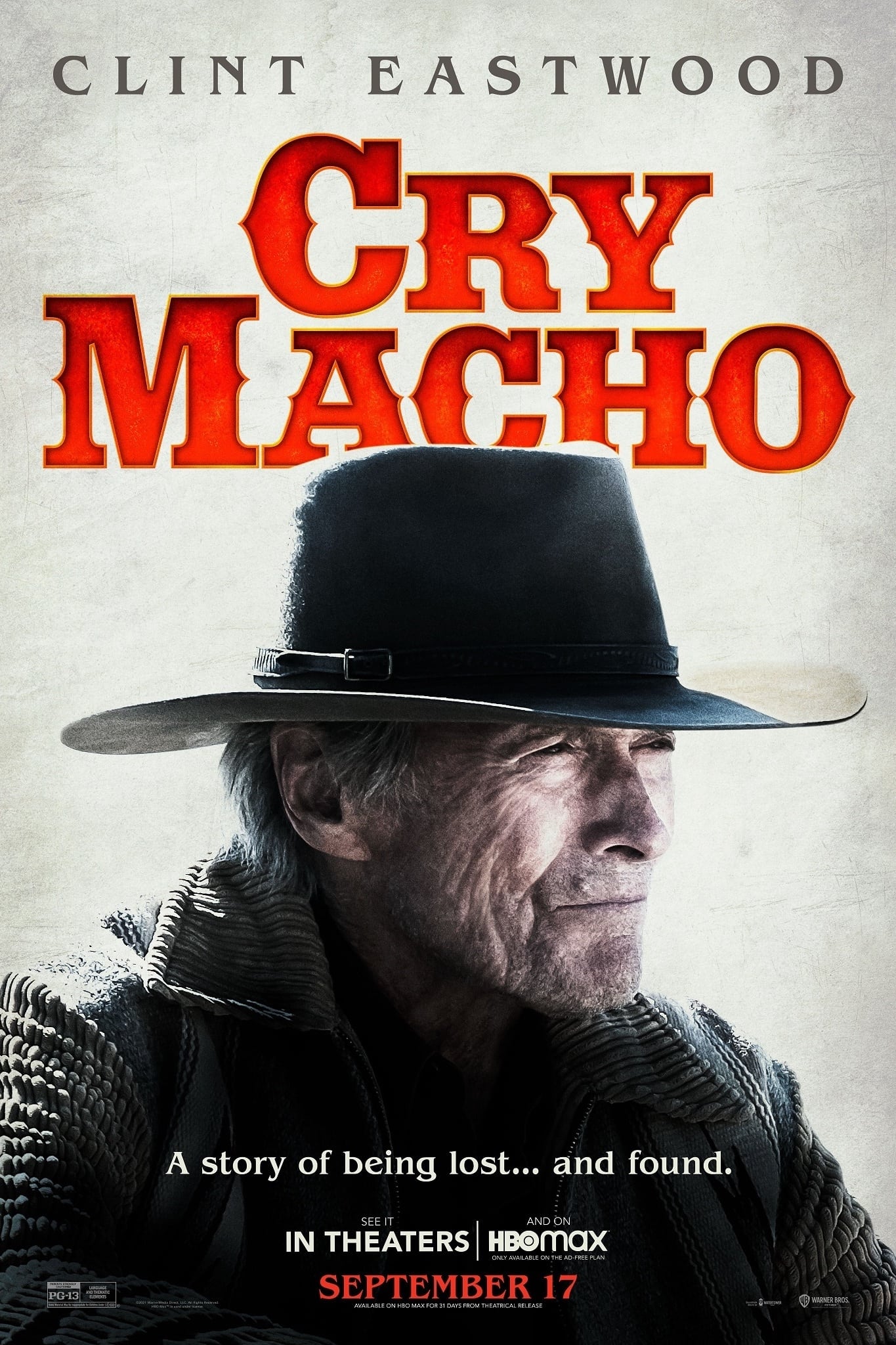

It would, at any rate, be a shame if Cry Macho is the last of Eastwood, because it's just not a very special movie otherwise. Gran Torino was a much more potent and effective elegy for Eastwood's star persona; even The Mule, which is not an especially impressive piece of cinema, does a better job of actually coming to grips with "the Clint Eastwood type". And his last directorial effort, 2019's Richard Jewell, while it felt not at all like a career summary, at least had the decency to be the most well-built film he'd made in over a decade at that point. Cry Macho is just kind of fluffy and pleasant, which already feels like an odd approach for something so charged with the possibility of violence and the reality of betrayal and disappointment. It is a film in which, far from testing himself on literally any level whatsoever, Eastwood seems content just to brag that he still hasn't died, and to parade his scrawny, weathered body around in front of the camera for us to enjoy the monumental screen presence that honestly isn't much more diluted now than it was during his brooding sex symbol days in the '60s and '70s. The man has charisma, and if Cry Macho really does have anything to say, it's as a referendum on the potency of honest-to-God movie star energy as a means for bending storytelling and psychology around the movie star. The film knows very well that we're not watching Mike Milo, whoever that is, we're watching our accumulated decades of associations with the man embodying him, and reflecting on how very clearly old Eastwood is, old but not apparently tiring, even as his voice has risen to a breathy rasp and his skin clings tightly to his slender frame, as he moves with determination even though the obvious creakiness of his bones. It is about how even the most ageless of all humans, the Movie Stars, eventually grow old and decay, and yet preserve the electricity and magnetism that made them stars in the first place.

At least, I cannot imagine that Eastwood wouldn't have realised that this was going to be the main effect of watching the film, particularly since he made the calculated choice to age into the role. Cry Macho has had a weird road to cinemas, beginning as a script that writer N. Richard Nash couldn't sell in the 1970s, upon which he converted it into a novel; that novel was very well received and was optioned by multiple different studios over the years, at which point Nash simply offered his original screenplay. Over the decades, it has been associated with several different stars in a rather wide age range; Eastwood declined the role in 1988, feeling that he wasn't old enough at the time, and after a mooted version starring Arnold Schwarzenegger fell through, he came back to it, bringing along with him screenwriter Nick Schenk, who also wrote... huh, Gran Torino and The Mule, what do you know.

Schenk's revised screenplay is what has now, all these decades later, reached the screen, and it's hard not to have the reaction, would Nash's have been better? At its very best, the current Cry Macho script is largely inoffensive as it works its way through clichés that it certainly appears to believe in, and treats respectfully. At its worst, we get the sluggish misery of the film's opening 20 minutes, which are just rotten with the very worst kind of "let me remind you of your own life story" exposition and the most plodding, hand-holding approach to establishing its themes, which are pretty obvious in part because they've been the themes of what feels like half of Eastwood's films by this point.

The story, set mostly in 1980, hinges on broken-down old Mike, who used to be a rodeo cowboy, and is now just deadwood, irritably grouching his way through retirement when his old boss, Howard Polk (Dwight Yoakam) offers him a job, though "offer" makes it sound nicer than it is. Howard's teenage son, Rafo (Eduoardo Minnett) is living in Mexico with his mother, Howard's dissolute ex Leta (Fernanda Urrejola), for reasons that Howard presents as being humane and fatherly and benign. It's very hard to believe him, what with him being played by Dwight Yoakam and all, but Mike doesn't really give a shit any way, so he travels south of the border and retrieves Rafo from the cock-fighting circuit where he's gone to prove his manhood and avoid a mother who doesn't have any interest in him anyway. So the two of them, and Rafo's beloved cock Macho, amble their way back to the States, stopping for a long time with cafe-owner Marta (Natalia Traven). As they do this, the brittle relationship between the old man and the boy starts to yield, kind of; it's not exactly that they start to become friendly as that Rafo starts to absorb what Mike is telling him about how the need to constantly prove oneself to be a tough manly man - to be macho - is a whole lot of bullshit, and that kind of retrograde masculinity just leads to you becoming a bitter and unpleasant old carcass like Mike himself.

"Eastwood plays an aging avatar of traditional matinee idol masculinity, here to inform us that traditional masculinity sucks" is the opposite of new: Unforgiven is now 29 years old. And he's gone back to that well plenty of times in those years. Even so, Cry Macho is a perfectly functional addition to the corpus, owing to how surprisingly nice it is. Eastwood has both starred in and directed nice movies, but not so very many, and that's part of what gives this the feeling of being a valediction: one last go-round, but this time just have fun, smile and laugh, unashamedly bask in the sentimentality of playing off of a raw kid, who like most untrained actors isn't terribly well-suited to Eastwood's hands-off approach to directing. Still, Minett's attempts to find a definition for Rafo are close enough to Rafo's own arc that it sort of ends up working; certainly, it doesn't threaten to wobble the film's foundations as badly as Bee Vang's performance as basically the same character did for Gran Torino. To say nothing of the catastrophe that was The 15:17 to Paris.

And that's the thing, really: 104 minutes (a nice running time) of watching Eastwood just being a warm, affable presence, which gets doubled once Traven shows up (she gives the film's only other credible performance), and they flirt in a relaxed, soft way, enjoying a remarkably natural and charming chemistry (surprisingly so, I'd say - Eastwood tends to ricochet right off his leading ladies, in my experience, unless they are Meryl Streep using every molecule of her talent to keep The Bridges of Madison County straight and true). It's a movie whose mood is perfectly matched to the dusty afternoon sun that dominates Ben Davis's extremely attractive, but not fussily so, cinematography, making rural New Mexico (filling in for both Texas and Mexico) glow with a simple, homey golden quality; even the shots of hot asphalt highways somehow acquire a kind of sharp beauty. It's a nice look, on top of everything, cozy and warm as a blanket, and that's pretty much what the movie is: something pleasant and cozy and immaculately free or urgency, whether it should have such a thing or not. As a fan of Eastwood's career on both sides of the camera, I appreciate this laconic opportunity to just hang out and enjoy his company one last time, but assuming this is his final statement on anything, it's awfully muffled and minor. I'm not going to tell the 91-year-old how to spend his creative energies, but this is a tossed-off shrug of a film, and nothing more - a pleasant enough experience if you're invested in Eastwood qua Eastwood, but not especially meaningful outside of that.

It would, at any rate, be a shame if Cry Macho is the last of Eastwood, because it's just not a very special movie otherwise. Gran Torino was a much more potent and effective elegy for Eastwood's star persona; even The Mule, which is not an especially impressive piece of cinema, does a better job of actually coming to grips with "the Clint Eastwood type". And his last directorial effort, 2019's Richard Jewell, while it felt not at all like a career summary, at least had the decency to be the most well-built film he'd made in over a decade at that point. Cry Macho is just kind of fluffy and pleasant, which already feels like an odd approach for something so charged with the possibility of violence and the reality of betrayal and disappointment. It is a film in which, far from testing himself on literally any level whatsoever, Eastwood seems content just to brag that he still hasn't died, and to parade his scrawny, weathered body around in front of the camera for us to enjoy the monumental screen presence that honestly isn't much more diluted now than it was during his brooding sex symbol days in the '60s and '70s. The man has charisma, and if Cry Macho really does have anything to say, it's as a referendum on the potency of honest-to-God movie star energy as a means for bending storytelling and psychology around the movie star. The film knows very well that we're not watching Mike Milo, whoever that is, we're watching our accumulated decades of associations with the man embodying him, and reflecting on how very clearly old Eastwood is, old but not apparently tiring, even as his voice has risen to a breathy rasp and his skin clings tightly to his slender frame, as he moves with determination even though the obvious creakiness of his bones. It is about how even the most ageless of all humans, the Movie Stars, eventually grow old and decay, and yet preserve the electricity and magnetism that made them stars in the first place.

At least, I cannot imagine that Eastwood wouldn't have realised that this was going to be the main effect of watching the film, particularly since he made the calculated choice to age into the role. Cry Macho has had a weird road to cinemas, beginning as a script that writer N. Richard Nash couldn't sell in the 1970s, upon which he converted it into a novel; that novel was very well received and was optioned by multiple different studios over the years, at which point Nash simply offered his original screenplay. Over the decades, it has been associated with several different stars in a rather wide age range; Eastwood declined the role in 1988, feeling that he wasn't old enough at the time, and after a mooted version starring Arnold Schwarzenegger fell through, he came back to it, bringing along with him screenwriter Nick Schenk, who also wrote... huh, Gran Torino and The Mule, what do you know.

Schenk's revised screenplay is what has now, all these decades later, reached the screen, and it's hard not to have the reaction, would Nash's have been better? At its very best, the current Cry Macho script is largely inoffensive as it works its way through clichés that it certainly appears to believe in, and treats respectfully. At its worst, we get the sluggish misery of the film's opening 20 minutes, which are just rotten with the very worst kind of "let me remind you of your own life story" exposition and the most plodding, hand-holding approach to establishing its themes, which are pretty obvious in part because they've been the themes of what feels like half of Eastwood's films by this point.

The story, set mostly in 1980, hinges on broken-down old Mike, who used to be a rodeo cowboy, and is now just deadwood, irritably grouching his way through retirement when his old boss, Howard Polk (Dwight Yoakam) offers him a job, though "offer" makes it sound nicer than it is. Howard's teenage son, Rafo (Eduoardo Minnett) is living in Mexico with his mother, Howard's dissolute ex Leta (Fernanda Urrejola), for reasons that Howard presents as being humane and fatherly and benign. It's very hard to believe him, what with him being played by Dwight Yoakam and all, but Mike doesn't really give a shit any way, so he travels south of the border and retrieves Rafo from the cock-fighting circuit where he's gone to prove his manhood and avoid a mother who doesn't have any interest in him anyway. So the two of them, and Rafo's beloved cock Macho, amble their way back to the States, stopping for a long time with cafe-owner Marta (Natalia Traven). As they do this, the brittle relationship between the old man and the boy starts to yield, kind of; it's not exactly that they start to become friendly as that Rafo starts to absorb what Mike is telling him about how the need to constantly prove oneself to be a tough manly man - to be macho - is a whole lot of bullshit, and that kind of retrograde masculinity just leads to you becoming a bitter and unpleasant old carcass like Mike himself.

"Eastwood plays an aging avatar of traditional matinee idol masculinity, here to inform us that traditional masculinity sucks" is the opposite of new: Unforgiven is now 29 years old. And he's gone back to that well plenty of times in those years. Even so, Cry Macho is a perfectly functional addition to the corpus, owing to how surprisingly nice it is. Eastwood has both starred in and directed nice movies, but not so very many, and that's part of what gives this the feeling of being a valediction: one last go-round, but this time just have fun, smile and laugh, unashamedly bask in the sentimentality of playing off of a raw kid, who like most untrained actors isn't terribly well-suited to Eastwood's hands-off approach to directing. Still, Minett's attempts to find a definition for Rafo are close enough to Rafo's own arc that it sort of ends up working; certainly, it doesn't threaten to wobble the film's foundations as badly as Bee Vang's performance as basically the same character did for Gran Torino. To say nothing of the catastrophe that was The 15:17 to Paris.

And that's the thing, really: 104 minutes (a nice running time) of watching Eastwood just being a warm, affable presence, which gets doubled once Traven shows up (she gives the film's only other credible performance), and they flirt in a relaxed, soft way, enjoying a remarkably natural and charming chemistry (surprisingly so, I'd say - Eastwood tends to ricochet right off his leading ladies, in my experience, unless they are Meryl Streep using every molecule of her talent to keep The Bridges of Madison County straight and true). It's a movie whose mood is perfectly matched to the dusty afternoon sun that dominates Ben Davis's extremely attractive, but not fussily so, cinematography, making rural New Mexico (filling in for both Texas and Mexico) glow with a simple, homey golden quality; even the shots of hot asphalt highways somehow acquire a kind of sharp beauty. It's a nice look, on top of everything, cozy and warm as a blanket, and that's pretty much what the movie is: something pleasant and cozy and immaculately free or urgency, whether it should have such a thing or not. As a fan of Eastwood's career on both sides of the camera, I appreciate this laconic opportunity to just hang out and enjoy his company one last time, but assuming this is his final statement on anything, it's awfully muffled and minor. I'm not going to tell the 91-year-old how to spend his creative energies, but this is a tossed-off shrug of a film, and nothing more - a pleasant enough experience if you're invested in Eastwood qua Eastwood, but not especially meaningful outside of that.