Lost in memories

There's simply no disentangling the things that are good about Reminiscence from the things that are bad. The film is the feature debut of writer-director Lisa Joy, who co-created the television series Westworld with her husband, Jonathan Nolan, and it is very much something that feels like it came from the mind of Christopher Nolan's sister-in-law. There's an unmistakable mechanical chilliness to it, an interest in following the logic of ideas rather than doing anything with characters, and of treating the whole thing as a casual experiment in how a gimmick intersects with standard narrative storytelling. None of this, for the record, is what I mean when I say "things that are bad", though I understand that other viewers might disagree with me.

Anyway, this definitely feels in the neighborhood of a Nolan brothers picture, but not exactly like their thing, which I assume is where Joy brings her special interests and obsessions to bear. And the most important of these obsessions by far is that she very obviously loves hard-boiled detective fiction from between the 1930s and 1940s, because what Reminiscence is, more than anything else, is a '40s-style detective story that just so happens to take place in a hellish future sci-fi world, and uses the signature technology of that world in developing its story. But in the hierarchy of the film's interests, science fiction of any sort takes an unmistakable backseat to tough, unsmiling men spitting out acid-laced lines of brutally cynical dialogue; gorgeous torch-singing dames who can't be trusted for a minute, but are mindblowingly sexy enough that, hey, who needs trust?; and a story that spends most of its time making sure the plot strands are good and snarled together, to a point that its virtually impossible to actually follow what the hell is going on until about two-thirds of the way through where a secondary villain sighs and says, effectively, "okay, fine, I'll just explain it to you, jeeze".

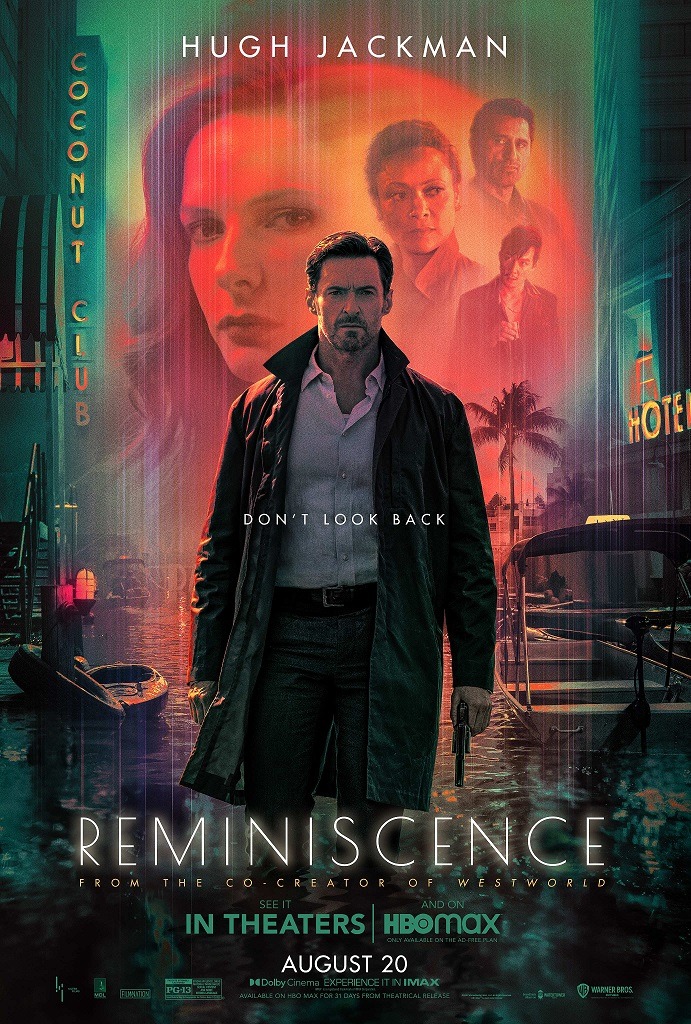

Which gets us back to the impossibility of disentangling the good from the bad, because when I say that, it probably sounds more like criticism than the praise I mean for it to be. The pleasure of a great film noir, and this is an awfully pure example of the form, with the "neo-" part of "neo-noir" mostly coming in the sci-fi trappings and nowhere else, generally isn't the solving of a mystery, but cracking open the skull of a broken-down chump and watching him wallow in his own foolishness. Reminiscence has one of those in the form of Nick Bannister (Hugh Jackman, playing only one note throughout the movie, but fortunately it's the right one), who lives in the waterlogged ruins of Miami sometime after World War III and climate change brought the ocean levels high enough to make a sort of miserable post-apocalyptic Venice of the city. He and his assistant, "Watts" Sanders (Thandiwe Newton), have some leftover tech that was developed for police interrogations: it allows the operator to guide the target through their memories, which are visualised as a three-dimensional, life-sized hologram. A flashback machine, in essence, which is exactly how Joy uses it in her script, and insofar as Reminiscence is engaged in any mindfucking, it's in the film's consistent habit of smudging the difference between "this is happening now", "this is a flashback", and "this is a projected memory that Nick is reviewing", though it always makes it clear which of the three we're looking at by the end of a given scene.

In the beastly world of the future, nobody wants to be alive in the present, so Nick and Watts have a profitable business helping people relive pleasant memories in full sound and color, and insofar as Reminscence has a human-scale theme, it's about the dangerously intoxicating pleasures of nostalgia as a way of not dealing with the problems of today. And back we go to Nick as a traditional film noir sap: at a certain point - this is one of the film's best ways of blurring past and present, so it seems to be happening now and then simultaneously - a beautiful redhead with a haunted look, Mae (Rebecca Ferguson) showed up at the office, hoping to jog her memory of where she left her keys. After barely any time plowing through her brain, Nick is hopelessly smitten, and when she suddenly vanishes a little bit after they start a heady love affair, he becomes monomaniacally focused on figuring out where she went. This involves lots of his own dwelling fruitlessly in a lost past, as he becomes a different version of the same nostalgia junkies he caters to, you might say. And Watts in fact does say it, very explicitly, because one of Joy's most Nolan-like tendencies as a writer is to minutely spell things out that made perfectly fine sense as innuendo, thanks.

The degree to which any of this is satisfying hinges on two things. One is the aggressiveness with which Reminiscence builds up its decayed world and the sense of miserable gloom hovering over it. In the future, the planet has gotten so hot that it's practically impossible to be outdoors in Miami during the daytime, so the entire culture of the city has pivoted to nighttime activities, a rather blunt but nevertheless effective way of amping up the noir blackness. The film is lucky to have as its cinematographer Paul Cameron, who had a real thing going there in the first half of the 2000s, based especially around 2004's Collateral (where he shared duties with Dion Beebe) and Man on Fire. Cameron has been around since then (he worked on Westworld, in fact), but none of his features I've seen since 2006's Déja Vu have captured what made those mid-'00s films so special. Reminiscence maybe doesn't quite get us back there - it's a bit heavy-handed with the color grading - but it's an awfully fine-looking bit of scummy urban nighttime nastiness, skewing heavily towards a color palette of bronze and corroded copper, and favoring hard edge lighting and murky key lights. It's a sharp, muggy, grimly exhausted look that gets at the hard, chunky blacks of golden-era noir in what barely qualifies as color cinematography, and the stuffy, ominous visual atmosphere this helps to create is the biggest part of what makes Reminiscence come together.

The other thing that this hinges on is the hard-boiledness of it all. It is unapologetic in its love of genre tropes, often allowing itself to feel downright corny and always feeling dated - even with all of the sci-fi elements plastered around the central mystery, the freshest the movie can do is to feel like something that might have come out in the late '90s or early '00s, from the same genre-mashing impulse that brought us Dark City and Minority Report. But much of what makes it dated and corny is much older still, starting with Nick's omnipresent voiceover dialogue, which Joy fearlessly over-writes to have way too much confusingly florid poetry, and which Jackson delivers with an ache in his voice to make it clear that he believes in that poetry, even if he's no good at making sense of it. Everything follows from that: the surprisingly unironic deployment of old-school femme fatale characterisation for Mae, who is magnificently played with layers of smoky sexuality, brokenness, and a diamond-sharp kernel of human morality by Ferguson, the best actor in a cast mostly just there to serve as set decoration (Newton gives the film's other actively good performance, but she's also tasked with selling the worst scene, by far, in the whole film; even worse, it is the last scene); the aforementioned snarled plot, which really doesn't seem to exist on any plane other than "you will trust that this will all come together or you won't, but you damn sure won't be able to follow it". But that's kind of the fun of a noir, which gets me back to my point from way back when: the point of Reminiscence isn't "what happened". It's that Nick is allowing himself to dive into the muddy mess of a convoluted plot full of sordid people just because he's obsessed with recapturing a few nice memories. The sloppiness of the storytelling is at least partially connected to that - no doubt, a less-sloppy script would be better, but there's a sense in which the impenetrability of the story is itself a sign of how dumb Nick is for trying to penetrate it. And while I'm not sure that Joy necessarily had that in mind as a strategy going into the film, it's a sign of how well she grasps the essential absurdity of noir that she was able to make it work.

Anyway, this definitely feels in the neighborhood of a Nolan brothers picture, but not exactly like their thing, which I assume is where Joy brings her special interests and obsessions to bear. And the most important of these obsessions by far is that she very obviously loves hard-boiled detective fiction from between the 1930s and 1940s, because what Reminiscence is, more than anything else, is a '40s-style detective story that just so happens to take place in a hellish future sci-fi world, and uses the signature technology of that world in developing its story. But in the hierarchy of the film's interests, science fiction of any sort takes an unmistakable backseat to tough, unsmiling men spitting out acid-laced lines of brutally cynical dialogue; gorgeous torch-singing dames who can't be trusted for a minute, but are mindblowingly sexy enough that, hey, who needs trust?; and a story that spends most of its time making sure the plot strands are good and snarled together, to a point that its virtually impossible to actually follow what the hell is going on until about two-thirds of the way through where a secondary villain sighs and says, effectively, "okay, fine, I'll just explain it to you, jeeze".

Which gets us back to the impossibility of disentangling the good from the bad, because when I say that, it probably sounds more like criticism than the praise I mean for it to be. The pleasure of a great film noir, and this is an awfully pure example of the form, with the "neo-" part of "neo-noir" mostly coming in the sci-fi trappings and nowhere else, generally isn't the solving of a mystery, but cracking open the skull of a broken-down chump and watching him wallow in his own foolishness. Reminiscence has one of those in the form of Nick Bannister (Hugh Jackman, playing only one note throughout the movie, but fortunately it's the right one), who lives in the waterlogged ruins of Miami sometime after World War III and climate change brought the ocean levels high enough to make a sort of miserable post-apocalyptic Venice of the city. He and his assistant, "Watts" Sanders (Thandiwe Newton), have some leftover tech that was developed for police interrogations: it allows the operator to guide the target through their memories, which are visualised as a three-dimensional, life-sized hologram. A flashback machine, in essence, which is exactly how Joy uses it in her script, and insofar as Reminiscence is engaged in any mindfucking, it's in the film's consistent habit of smudging the difference between "this is happening now", "this is a flashback", and "this is a projected memory that Nick is reviewing", though it always makes it clear which of the three we're looking at by the end of a given scene.

In the beastly world of the future, nobody wants to be alive in the present, so Nick and Watts have a profitable business helping people relive pleasant memories in full sound and color, and insofar as Reminscence has a human-scale theme, it's about the dangerously intoxicating pleasures of nostalgia as a way of not dealing with the problems of today. And back we go to Nick as a traditional film noir sap: at a certain point - this is one of the film's best ways of blurring past and present, so it seems to be happening now and then simultaneously - a beautiful redhead with a haunted look, Mae (Rebecca Ferguson) showed up at the office, hoping to jog her memory of where she left her keys. After barely any time plowing through her brain, Nick is hopelessly smitten, and when she suddenly vanishes a little bit after they start a heady love affair, he becomes monomaniacally focused on figuring out where she went. This involves lots of his own dwelling fruitlessly in a lost past, as he becomes a different version of the same nostalgia junkies he caters to, you might say. And Watts in fact does say it, very explicitly, because one of Joy's most Nolan-like tendencies as a writer is to minutely spell things out that made perfectly fine sense as innuendo, thanks.

The degree to which any of this is satisfying hinges on two things. One is the aggressiveness with which Reminiscence builds up its decayed world and the sense of miserable gloom hovering over it. In the future, the planet has gotten so hot that it's practically impossible to be outdoors in Miami during the daytime, so the entire culture of the city has pivoted to nighttime activities, a rather blunt but nevertheless effective way of amping up the noir blackness. The film is lucky to have as its cinematographer Paul Cameron, who had a real thing going there in the first half of the 2000s, based especially around 2004's Collateral (where he shared duties with Dion Beebe) and Man on Fire. Cameron has been around since then (he worked on Westworld, in fact), but none of his features I've seen since 2006's Déja Vu have captured what made those mid-'00s films so special. Reminiscence maybe doesn't quite get us back there - it's a bit heavy-handed with the color grading - but it's an awfully fine-looking bit of scummy urban nighttime nastiness, skewing heavily towards a color palette of bronze and corroded copper, and favoring hard edge lighting and murky key lights. It's a sharp, muggy, grimly exhausted look that gets at the hard, chunky blacks of golden-era noir in what barely qualifies as color cinematography, and the stuffy, ominous visual atmosphere this helps to create is the biggest part of what makes Reminiscence come together.

The other thing that this hinges on is the hard-boiledness of it all. It is unapologetic in its love of genre tropes, often allowing itself to feel downright corny and always feeling dated - even with all of the sci-fi elements plastered around the central mystery, the freshest the movie can do is to feel like something that might have come out in the late '90s or early '00s, from the same genre-mashing impulse that brought us Dark City and Minority Report. But much of what makes it dated and corny is much older still, starting with Nick's omnipresent voiceover dialogue, which Joy fearlessly over-writes to have way too much confusingly florid poetry, and which Jackson delivers with an ache in his voice to make it clear that he believes in that poetry, even if he's no good at making sense of it. Everything follows from that: the surprisingly unironic deployment of old-school femme fatale characterisation for Mae, who is magnificently played with layers of smoky sexuality, brokenness, and a diamond-sharp kernel of human morality by Ferguson, the best actor in a cast mostly just there to serve as set decoration (Newton gives the film's other actively good performance, but she's also tasked with selling the worst scene, by far, in the whole film; even worse, it is the last scene); the aforementioned snarled plot, which really doesn't seem to exist on any plane other than "you will trust that this will all come together or you won't, but you damn sure won't be able to follow it". But that's kind of the fun of a noir, which gets me back to my point from way back when: the point of Reminiscence isn't "what happened". It's that Nick is allowing himself to dive into the muddy mess of a convoluted plot full of sordid people just because he's obsessed with recapturing a few nice memories. The sloppiness of the storytelling is at least partially connected to that - no doubt, a less-sloppy script would be better, but there's a sense in which the impenetrability of the story is itself a sign of how dumb Nick is for trying to penetrate it. And while I'm not sure that Joy necessarily had that in mind as a strategy going into the film, it's a sign of how well she grasps the essential absurdity of noir that she was able to make it work.

Categories: film noir, mysteries, post-apocalypse, science fiction, summer movies, thrillers