Detroit blues

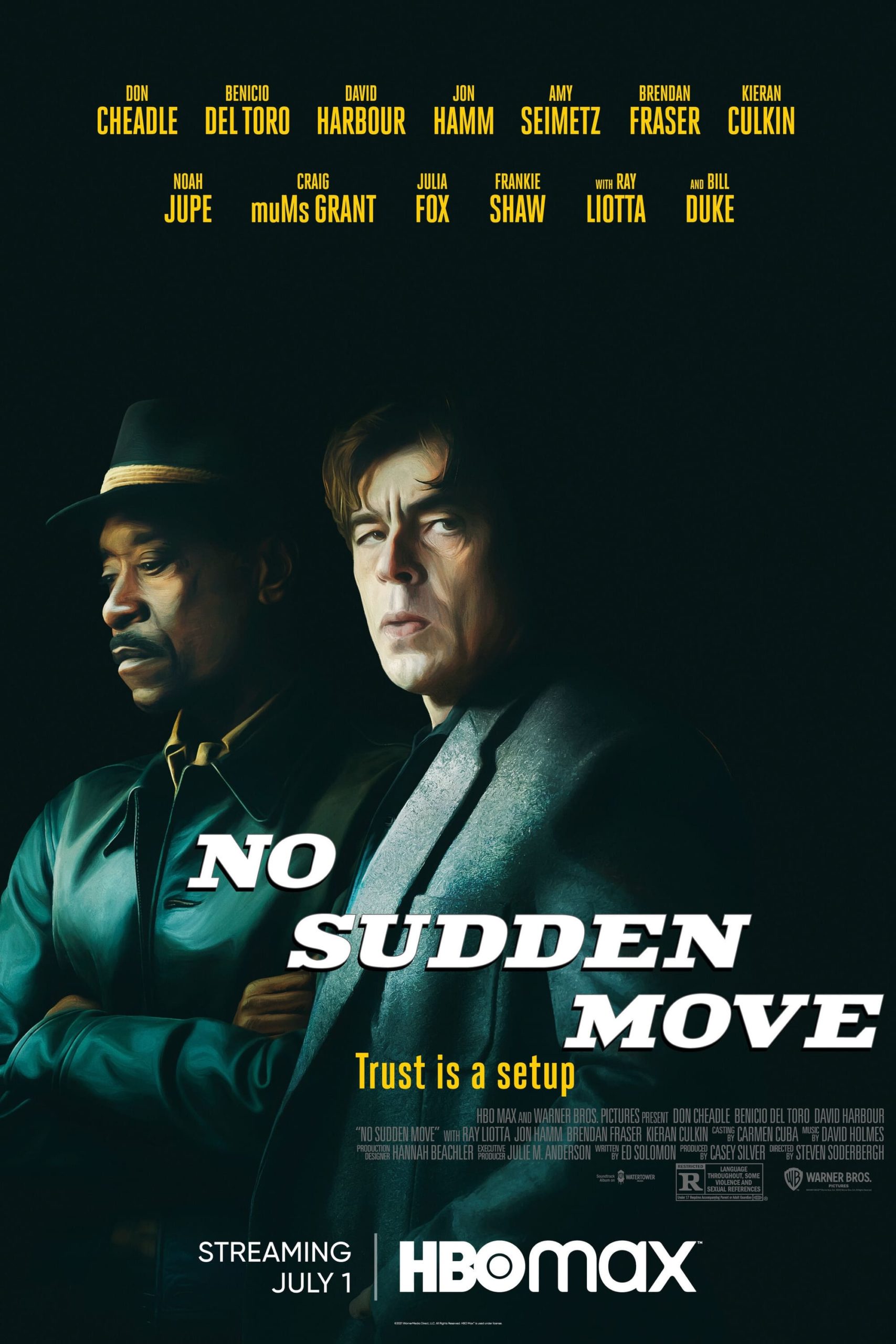

Notwithstanding its title, one of the most acutely generic and forgettable (not to mention, inapt) I have encountered in an age, No Sudden Move is a triumph of writing, with a hell of a script by Ed Solomon that's as good as any that director Steven Soderbergh has worked with in a good ten or fifteen years. And it has an even better ensemble cast, a seemingly unending flow of actors sidling into to an ever-messier human drama that wants to be arch and mannered twice over, first as a 1950s period film and second as a gravely snappy film noir pastiche, but also wants to have us believe in the emotions of the characters, and demands much of them if this is going to happen. I'm not going to call it the best cast Soderbergh has ever worked with, since his filmography is particularly well-stocked with unreasonably impressive casts. But I will say that the thought of calling it that certainly did cross my mind.

All of that being said, it's unfortunate, even maddening, that my knee-jerk response, one that always hovered at the top of my reaction no matter how much I was enjoying watching the actors navigate the plot turns, was "fuck my life, is it ever ugly". Soderbergh, as he often does, works here as his own cinematographer and editor, appearing as usual under the names Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard, respectively. And I will say that Ms. Bernard is in perfectly fine form this time around. It's not going to change the way you think of editing or anything like that, but the film advances with crisp, sharp cuts that march us steadily through dense scenes of plot and dialogue without feeling rushed, and allows us to sink uncomfortably into the moments where the plot seems to bunch up and the characters are even more confused than we are. But Mr. Andrews really needs to get a good shaking. We are now in year four of Soderbergh's iPhone epoch, and while I'm fairly sure that No Sudden Move was shot on actual movie cameras, the director/cinematograpaher's discovery of extreme wide angle lenses has become really just quite insufferable at this point. I don't know if every shot in No Sudden Move was filmed with a fish-eye lens; but I wouldn't doubt it for a moment if I was told that was so. Especially since Soderbergh seems so hellbent on making sure we notice it all the time, by filling his movie up with panning shots, the specific form of camera movement best-suited to calling attention to fish-eye lenses; they create the feeling of the entire world sort of melting around the viewer in a huge parabolic curve with its point right square in the center of the frame. But even when we're spared that sight, No Sudden Move is full of compositions where one character will be just to the side of the center of the frame, and the other character will be most of the way to the other side, and it feels like they're standing about 300 feet away from each other while gathered around the same table. It's awful and disgusting, but at least unlike the panning shots, it didn't make my eyes water and turn a headache on like a light switch.

Just to be clear, this is very obviously a deliberate, considered choice that Soderbergh has made, not some bizarre fuck-up. I don't know why he made the choice, and I don't like, is all. It has left a movie that otherwise feels like it has the stuff to be an excellent tightly-coiled thriller, the proverbial "thoughtful movie for adults" that we get so few of, ending up as being honestly a bit tiring to watch. But having now gone all-in on accentuating the negative, let me at least return to the point: it does have the stuff to be a tightly-coiled thriller. It's all about a bunch of different people who know enough to dimly grasp that there is some kind of situation around them, that situation involves the potential for making many tens of thousands of dollars, and it's really hard to figure out who else knows what's actually going on, and who else is just dimly grasping from their own distinct position in the dark. It's set in Detroit, 1954, and both the year and the place matter, though the film is weakest when it tries to actually grapple with the specifics of history (like a great many Soderbergh films, it's about the devouring hunger of capitalism in general, and specifically about institutional racism in urban planning and how massive corporations can insulate themselves from ever having to face the consequences of their actions. It is not about either one of these things in a very dedicated or insightful way). It's at its best when it's watching the characters being smacked around by that history like billiard balls. The names of the balls, roughly in order of appearance, includes Curt Goynes (Don Cheadle), a newly-released ex-con, and Ronald Russo (Benicio Del Toro), both of them involved in Detroit's organised crime; they're hired by Doug Jones (Brendan Fraser, who I've never seen close to this good in anything; he's gained a lot of weight since his heyday, and with it even more screen presence and quiet authority) to serve as "babysitters" - men in masks with guns holding a family hostage - to make Matt Wertz (David Harbour) retrieve some extremely significant documents from his boss's safe at the accounting firm where he works. Curt and Ronald keep Matt's wife Mary (Amy Seimetz, my uncertain pick for best out of a really world-class group of performances) and their kids locked down while Matt and the very quiet gangster Charley (Kieran Culkin) go to Matt's office, where there are no documents, and that's where things start to go all wobbly.

As the film progresses, more and more people are added to it, to the point that just keeping track of who knows who else and what their power dynamics look like feels like it needs a flow-chart: there as love affairs, mob bosses - one played by Bill Duke with maximum "cinema legend" menacing charisma - cops trying to figure out what the hell is going on, and Curt and Ronald deciding in best film noir tradition that they're smart enough to lie to a bunch of extremely powerful men who are very protective of their money, and learning at great length and over multiple scenes that they are in fact nowhere near that smart, and indeed their enemies are in some cases counting on them making that mistake.

Whether this ultimately does anything that's not a standard part of the '50s crime movie template, I can't say - I'm sure it thinks being about racism and corporatism are those things, but '50s movies already did that and anyway, like I said, No Sudden Move isn't really very good at digging into those things. Instead, it feels like it's mostly about the game of trudging into a scenario that gets more and more overrun with weeds the more you hack at it, growing darker and thicker with every new character who arrives in the plot, bringing with them a new network of relationships and goal for the all-important document. The characters are written to be both desperate humans and crime movie types, with dialogue that skews just far enough towards the brittle snappiness of a mannered genre exercise for it to feel like a proper Movie, with a certain dark wit gliding through all of its scenes. This shows up in some obvious stand-out scenes - Harbour turning into a panicking mess as he desperately apologises to the man he's beating up for not being allowed to explain what's going on is dark comedy of the best sort - but it's much more about the overall mood the film creates, a lightly snippy cynicism mixed with cool, admiring characters for being stubborn even when it's clear that it's not helping at all, and for making and executing elaborate plans even when they turn out to just be a meaningless parenthetical.

Basically, it's taking the breezy indie caper vibe of Out of Sight and the studio movie version of same of Ocean's Eleven, and running them headlong into the caustic helplessness of film noir while preserving the feeling of talented movie stars having a very fun time playing petty criminals and gangsters. I cannot convince myself if there's more to it than just pulling out genre tropes and having a good time with them, but No Sudden Move does that so well that it's hard to feel like that's a problem.

But fuck my life, is it ever ugly.

All of that being said, it's unfortunate, even maddening, that my knee-jerk response, one that always hovered at the top of my reaction no matter how much I was enjoying watching the actors navigate the plot turns, was "fuck my life, is it ever ugly". Soderbergh, as he often does, works here as his own cinematographer and editor, appearing as usual under the names Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard, respectively. And I will say that Ms. Bernard is in perfectly fine form this time around. It's not going to change the way you think of editing or anything like that, but the film advances with crisp, sharp cuts that march us steadily through dense scenes of plot and dialogue without feeling rushed, and allows us to sink uncomfortably into the moments where the plot seems to bunch up and the characters are even more confused than we are. But Mr. Andrews really needs to get a good shaking. We are now in year four of Soderbergh's iPhone epoch, and while I'm fairly sure that No Sudden Move was shot on actual movie cameras, the director/cinematograpaher's discovery of extreme wide angle lenses has become really just quite insufferable at this point. I don't know if every shot in No Sudden Move was filmed with a fish-eye lens; but I wouldn't doubt it for a moment if I was told that was so. Especially since Soderbergh seems so hellbent on making sure we notice it all the time, by filling his movie up with panning shots, the specific form of camera movement best-suited to calling attention to fish-eye lenses; they create the feeling of the entire world sort of melting around the viewer in a huge parabolic curve with its point right square in the center of the frame. But even when we're spared that sight, No Sudden Move is full of compositions where one character will be just to the side of the center of the frame, and the other character will be most of the way to the other side, and it feels like they're standing about 300 feet away from each other while gathered around the same table. It's awful and disgusting, but at least unlike the panning shots, it didn't make my eyes water and turn a headache on like a light switch.

Just to be clear, this is very obviously a deliberate, considered choice that Soderbergh has made, not some bizarre fuck-up. I don't know why he made the choice, and I don't like, is all. It has left a movie that otherwise feels like it has the stuff to be an excellent tightly-coiled thriller, the proverbial "thoughtful movie for adults" that we get so few of, ending up as being honestly a bit tiring to watch. But having now gone all-in on accentuating the negative, let me at least return to the point: it does have the stuff to be a tightly-coiled thriller. It's all about a bunch of different people who know enough to dimly grasp that there is some kind of situation around them, that situation involves the potential for making many tens of thousands of dollars, and it's really hard to figure out who else knows what's actually going on, and who else is just dimly grasping from their own distinct position in the dark. It's set in Detroit, 1954, and both the year and the place matter, though the film is weakest when it tries to actually grapple with the specifics of history (like a great many Soderbergh films, it's about the devouring hunger of capitalism in general, and specifically about institutional racism in urban planning and how massive corporations can insulate themselves from ever having to face the consequences of their actions. It is not about either one of these things in a very dedicated or insightful way). It's at its best when it's watching the characters being smacked around by that history like billiard balls. The names of the balls, roughly in order of appearance, includes Curt Goynes (Don Cheadle), a newly-released ex-con, and Ronald Russo (Benicio Del Toro), both of them involved in Detroit's organised crime; they're hired by Doug Jones (Brendan Fraser, who I've never seen close to this good in anything; he's gained a lot of weight since his heyday, and with it even more screen presence and quiet authority) to serve as "babysitters" - men in masks with guns holding a family hostage - to make Matt Wertz (David Harbour) retrieve some extremely significant documents from his boss's safe at the accounting firm where he works. Curt and Ronald keep Matt's wife Mary (Amy Seimetz, my uncertain pick for best out of a really world-class group of performances) and their kids locked down while Matt and the very quiet gangster Charley (Kieran Culkin) go to Matt's office, where there are no documents, and that's where things start to go all wobbly.

As the film progresses, more and more people are added to it, to the point that just keeping track of who knows who else and what their power dynamics look like feels like it needs a flow-chart: there as love affairs, mob bosses - one played by Bill Duke with maximum "cinema legend" menacing charisma - cops trying to figure out what the hell is going on, and Curt and Ronald deciding in best film noir tradition that they're smart enough to lie to a bunch of extremely powerful men who are very protective of their money, and learning at great length and over multiple scenes that they are in fact nowhere near that smart, and indeed their enemies are in some cases counting on them making that mistake.

Whether this ultimately does anything that's not a standard part of the '50s crime movie template, I can't say - I'm sure it thinks being about racism and corporatism are those things, but '50s movies already did that and anyway, like I said, No Sudden Move isn't really very good at digging into those things. Instead, it feels like it's mostly about the game of trudging into a scenario that gets more and more overrun with weeds the more you hack at it, growing darker and thicker with every new character who arrives in the plot, bringing with them a new network of relationships and goal for the all-important document. The characters are written to be both desperate humans and crime movie types, with dialogue that skews just far enough towards the brittle snappiness of a mannered genre exercise for it to feel like a proper Movie, with a certain dark wit gliding through all of its scenes. This shows up in some obvious stand-out scenes - Harbour turning into a panicking mess as he desperately apologises to the man he's beating up for not being allowed to explain what's going on is dark comedy of the best sort - but it's much more about the overall mood the film creates, a lightly snippy cynicism mixed with cool, admiring characters for being stubborn even when it's clear that it's not helping at all, and for making and executing elaborate plans even when they turn out to just be a meaningless parenthetical.

Basically, it's taking the breezy indie caper vibe of Out of Sight and the studio movie version of same of Ocean's Eleven, and running them headlong into the caustic helplessness of film noir while preserving the feeling of talented movie stars having a very fun time playing petty criminals and gangsters. I cannot convince myself if there's more to it than just pulling out genre tropes and having a good time with them, but No Sudden Move does that so well that it's hard to feel like that's a problem.

But fuck my life, is it ever ugly.