Blockbuster History: Looney Tunes in the real world

Intermittently throughout the summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to a major new release. This week: after 25 years, Space Jam: A New Legacy returns the classic animated figures of the Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies series to the basketball court, a place where they do not and have never belonged. Let us instead spend a moment appreciating the last time they appeared in a theatrical feature that doesn't feel at least partially motivated by screeching contempt for the characters.

I do not know that any movie ever made has had a lower bar to clear than Looney Tunes: Back in Action had to clear when it opened in November, 2003: as long as it was better than 1996's Space Jam, the film could be plausibly described as a success. Since a film could be truly rancid and horrible, barely even functional as a piece of entertainment, and still be better than Space Jam, it is perhaps the case that Back in Action doesn't really deserve all that much credit for managing this feat. But even if raise the standards, all the way up to "be actually worth watching", I think this still passes that mark with flying colors. Ever since the Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies series came to their functional end in 1969 (or 1963, if you are a purist), Warner Bros. has periodically tried to do something to keep the characters alive and marketable, usually to fairly dispiriting ends; Back in Action , which drops the animated characters into a live-action spy thriller that's mostly about poking fun at the film industry, is one of the very few attempts that is entirely worth watching and successful much more often than not.

Which is to say: it isn't completely successful. And one of the people who held that opinion was director Joe Dante, whose time as a significant Hollywood filmmaker effectively comes to an end here, having pretty much run out of financially successful movies in the 1980s, and coasted largely on fading goodwill for the decade to follow. Back in Action cost a reported $80 million, which is a lot of money but maybe not an indefensible lot of money, given that Space Jam grossed around three times that much worldwide on the same reported budget; it ended up taking in less than $70 million, which means that it actually managed to lose more than Dante's 1990 Gremlins 2: The New Batch, his last film with Warners, which had already lost the kind of money that would make a sensible studio executive probably want to avoid ever working with Dante again. Fortunately, the Warner people were being, for that moment in time, not even a little bit sensible, and so Dante got to fulfill what really was the destiny of his entire career, working with the wild absurdist animated slapstick of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck (both of them voiced here by Joe Alaskey, whose Bugs is excellent and whose Daffy gets the job done) and the rest that had informed so very many of his live-action features. In the wake of the grave catastrophe of Back in Action's swift and ugly death at the box office, Dante has kept himself busy with TV, a couple of features that basically didn't get theatrical releases at all, and a couple of segments in anthology films; we are not likely to see another project at this scale, setting huge piles of studio money on fire to create highly idiosyncratic little indulgence in personal fascinations that require massive effects budgets to realise. But at least his last hurrah was a delightful and bombastic one.

(It is also, for what it's worth, the last credit for composer Jerry Goldsmith, who grew weak enough by the end that he couldn't finish the job; John Debney took over the last chunk of the movie. It is not, I am sorry to say, a particularly noteworthy Goldsmith score, with the most interesting part being an unexpected and frankly unnecessary cameo of the "Gremlin Rag" he composed for Dante's Gremlins many years earlier).

Again, though, that's not actually an opinion held by Dante himself, who felt that he and screenwriter Larry Doyle and animation director Eric Goldberg - one of the major figures at Disney during their 1990s renaissance - were too constrained by the studio's requirements of the project. And while I don't know specifically what elements of Back in Action fell particularly far short of Dante's hopes and dreams for the picture, I will concede this much of the point: there are some unmistakable problems with the the film. The biggest and most persistent is also the one that probably cannot be solved no matter how much creative freedom is given to the most passionate and talented fans of the material: the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies are one-reelers, seven to eight minutes of concentrated gag-based comedy that routinely made a joke about how much they weren't functional narratives. It is not impossible to make an entire feature-length film that's a mostly plotless collection of gags, and have it work: Jacques Tati made at least three out-and-out masterpieces that way, and one of those is in excess of two hours. But, I mean, he's French. Dante and Doyle certainly meant well, and their energy in constructing gag after gag after gag until Back in Action has finally landed at 93 minutes, with credits, is unflagging. But it's a long time to go without a break, and the scrawny little doodle of a narrative lashing everything together somehow feels all the scrawnier for being asked to stand up for that length of time.

The rest of the problems are all localised, a matter of individual gags and routines that just don't play the way the filmmakers wanted them to. Which is really the only problem a film like this could have, given that it is at heart nothing but a long chain of gags, sometimes with only the most cursory transition between them. I will say this, at least: the failures of Back in Action tend to be large and fearless failures. Such as Steve Martin's performance as the villain, chairman of the ACME Company, who is trying to find a magical monkey statue that can turn all of humanity into monkeys, so he can have them manufacture an infinite number of shoddy goods at the ACME factory, whereupon he will turn them back into humans, and sell them the shoddy goods he has thus stockpiled. Tasked with playing a live-action cartoon, Martin holds nothing back whatsoever, flinging his body around like a ragdoll (indeed, one of the running gags is that his movements tend to make him almost, but not quite, fall over backawards), swallowing his lips, disappearing into his incredibly awful wig and giant glasses, and delivering every line with a bellowing melodramatic purr. It is a lot of acting, and good for him; I am tempted to say it never works. The single best part of Martin's entire performance, wincing offscreen as he hears Wile E. Coyote crashing into obstacles, is also the smallest and most subdued, though only in this context would Martin's exaggerated rubber-faced reaction shots count as "subdued". But he went for it, bless him.

My lord, that's a whole lot of pissing on a movie that I genuinely love. This is partially because it's easier to identify the flaws in Back in Action; the successes are much more about a freestanding mood it creates, one that the individual viewer either clicks with, or doesn't. Dante's main job as a filmmaker has been to clear the way for lots of very elaborate silliness to spin out, verbally and visually, at extraordinary cost to Warner Bros. Back in Action is a thunderously elaborate movie, an endless line of ludicrously overdesigned spaces full of visual gags. The most inspired of this is Area 52, overseen by the pleasant mad scientist Mother (Joan Cusack, whose twitchy cartoon energy works in all the ways that Martin's, for whatever reason, doesn't; it's reminiscent of what she did in Toys, only better. Or, at least, this movie knows better what to do with her); it's a jam-packed room full of all the B-movie references a legendary B-movie nerd like Dante can cram into one space, with a Triffid and a Metaluna mutant and a Dalek and God knows what all shoving their way into one generously busy widescreen frame. But even in more generic locations - the Warner studio office, a movie star's mansion in Hollywood - there's a sense of exaggerated movie-movie bigness in the giant imposing glass walls of the office, or the trapped-in-the-1920s lines and furniture in the mansion.

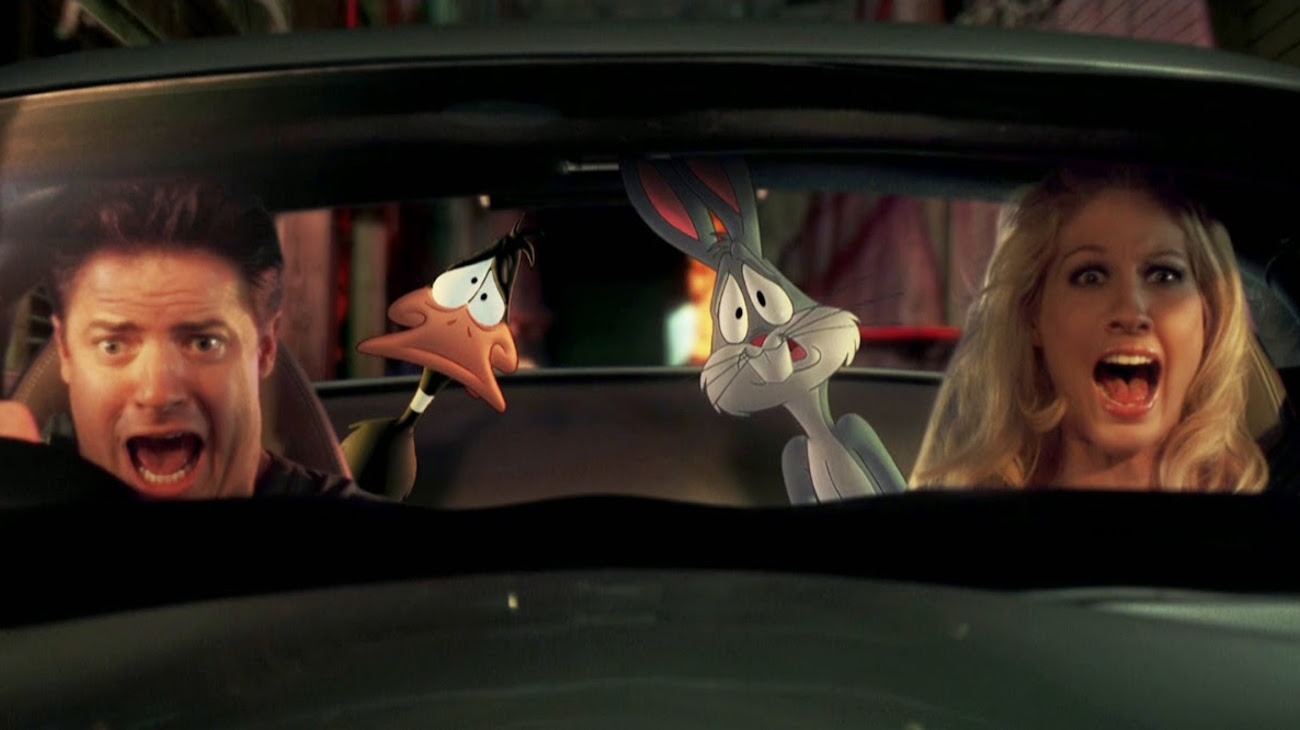

And then there's the verbal humor, full of wordplay and deadpan metajokes; the whole plot, once you shake out the Bondian supervillain part, is basically about how dumb Warner Bros. would be to try to make a feature film version of the Looney Tunes, and how lifelessly mercenary the decision-making processes in the film industry are, with their soul-sucking focus on brand extensions and marketing-friendly creative decisions. The film's antihero, who turns eventually into a co-protagonist, is a development executive played by Jenna Elfman, committing hard to being as plastic and unamusing as possible until that turn happens. None of this feels like it rises up to the level of satire, really, nor any serious attempt to bite at Warners; it's more just the same jolly absurd nonsense as all the rest of the jokes, a 21st Century freshening-up of the old Tex Avery "I do this to him through the whole picture" kind of self-referential gag where everybody onscreen knows that it's a movie made for crassly commercial reasons, but since we all know that, we can still go about the business of having fun and not pretending like we're dealing with anything to be taken seriously. And that really is the vibe of the whole film, ably carried out by Dante and shouldered by actual protagonist Brendan Fraser, whose bland "cheap movie star" good looks are perfect for this role, and whose comic timing turns out to be one of the film's best strengths, especially his ability to shoot glances right into the camera without going all the way to mugging or pulling faces. He's also, by a fair margin, the best human in the cast at interacting with the spaces where animated characters are to be plugged in later.

And that gets us to the most important part of all, which is of course the Looney Tunes part of Looney Tunes: Back in Action. Speaking as a diehard fan of the short film series, which I have numerous times suggested is the most important American contribution to the art form of cinema, I am very happy with what these other diehard fans have given me. You have to go all the way back to the 1950s and the last years of the Golden Age of Hollywood short film animation to find another project that cares so very much for these characters, for the specific breed of comedy that they were used to create, and for their wonderfully expressive designs. Bringing Goldberg on to direct the animation was one of the best decisions that ever got made in the production of the film; he was the closest thing Disney had to a Warner-style animator, and his work supervising the Genie in Aladdin, a character of physically unstable lines and a tendency towards exaggerated caricature, was the closest that studio ever got to the kind of work that was the foundation of classic-era Looney Tunes. So on the one hand, we have a man who knows the material, maybe as well as anybody working in animation in the early 2000s did. And on the other hand, we have a man who honed his talents working in a studio that turned the most elaborate, technically complex animation that had ever existed.

Both of these threads combine in Back in Action, whose visual style is primarily built around answering the question, "what if the Looney Tunes characters actually existed in the three-dimensional world of humans?" One of the most noticeable things about this film: the camera is restless as hell. Tracking shots abound, moments where it rotates around the action in a half-circle are only a bit less common, and the feeling one gets is of constant, almost nervous movement. As much as anything else, the purpose of this seems to be just to prove that they could do it: convincingly placing two-dimensional drawings into a three-dimensional space is already a technical feat, but adding constant camera movement to it makes it the kind of unnecessarily difficult task that only makes sense if e.g. Warner Bros. has given you $80 million and you are not very concerned with making sure that they get it back. That, coupled with the extremely detailed shading Goldberg applies to the characters to make them feel like three-dimensional figures interacting with real-world light sources puts Back in Action second to only 1988's masterpiece-level Who Framed Roger Rabbit in all the decades of hybridising hand-drawn animation with live-action footage.

None of which would matter if they weren't the Looney Tunes, executed with reverence and enthusiasm by filmmakers and animators who are palpably delighted to be making new old-fashioned slapstick cartoons. At times, the film errs on the side of too much awestruck fannish glee; for example, the opening is a fairly direct remake of the cartoons of the iconic Hunting Trilogy, done with much more technical panache, and it is firstly the case that the panache does it no good. It is secondly the case that there's a certain airlessness to the re-enactment of old gags, and Back in Action never does entirely shake off a slight feeling of ritualism, a feeling that we must very lovingly worship these characters, and not just laugh at them. Not great for the characters, not great for the jokes, which are sometimes more "I appreciate the structure of that joke" funny and less actually funny. But pretty much always great for the animation, at least, which has a vigorous squashy, stretchy quality that isn't really seen anywhere else in 21st Century theatrical animation - nor in 20th Century animation for a good 40 years before it was made, for that matter. It's a soppy love letter to what was in 2003 and is still a dead art form, and as someone who considers it to be one of the most important art forms in the history of the cinema, I find it all very winning and contenting and delightful, no matter how imperfect.

I do not know that any movie ever made has had a lower bar to clear than Looney Tunes: Back in Action had to clear when it opened in November, 2003: as long as it was better than 1996's Space Jam, the film could be plausibly described as a success. Since a film could be truly rancid and horrible, barely even functional as a piece of entertainment, and still be better than Space Jam, it is perhaps the case that Back in Action doesn't really deserve all that much credit for managing this feat. But even if raise the standards, all the way up to "be actually worth watching", I think this still passes that mark with flying colors. Ever since the Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies series came to their functional end in 1969 (or 1963, if you are a purist), Warner Bros. has periodically tried to do something to keep the characters alive and marketable, usually to fairly dispiriting ends; Back in Action , which drops the animated characters into a live-action spy thriller that's mostly about poking fun at the film industry, is one of the very few attempts that is entirely worth watching and successful much more often than not.

Which is to say: it isn't completely successful. And one of the people who held that opinion was director Joe Dante, whose time as a significant Hollywood filmmaker effectively comes to an end here, having pretty much run out of financially successful movies in the 1980s, and coasted largely on fading goodwill for the decade to follow. Back in Action cost a reported $80 million, which is a lot of money but maybe not an indefensible lot of money, given that Space Jam grossed around three times that much worldwide on the same reported budget; it ended up taking in less than $70 million, which means that it actually managed to lose more than Dante's 1990 Gremlins 2: The New Batch, his last film with Warners, which had already lost the kind of money that would make a sensible studio executive probably want to avoid ever working with Dante again. Fortunately, the Warner people were being, for that moment in time, not even a little bit sensible, and so Dante got to fulfill what really was the destiny of his entire career, working with the wild absurdist animated slapstick of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck (both of them voiced here by Joe Alaskey, whose Bugs is excellent and whose Daffy gets the job done) and the rest that had informed so very many of his live-action features. In the wake of the grave catastrophe of Back in Action's swift and ugly death at the box office, Dante has kept himself busy with TV, a couple of features that basically didn't get theatrical releases at all, and a couple of segments in anthology films; we are not likely to see another project at this scale, setting huge piles of studio money on fire to create highly idiosyncratic little indulgence in personal fascinations that require massive effects budgets to realise. But at least his last hurrah was a delightful and bombastic one.

(It is also, for what it's worth, the last credit for composer Jerry Goldsmith, who grew weak enough by the end that he couldn't finish the job; John Debney took over the last chunk of the movie. It is not, I am sorry to say, a particularly noteworthy Goldsmith score, with the most interesting part being an unexpected and frankly unnecessary cameo of the "Gremlin Rag" he composed for Dante's Gremlins many years earlier).

Again, though, that's not actually an opinion held by Dante himself, who felt that he and screenwriter Larry Doyle and animation director Eric Goldberg - one of the major figures at Disney during their 1990s renaissance - were too constrained by the studio's requirements of the project. And while I don't know specifically what elements of Back in Action fell particularly far short of Dante's hopes and dreams for the picture, I will concede this much of the point: there are some unmistakable problems with the the film. The biggest and most persistent is also the one that probably cannot be solved no matter how much creative freedom is given to the most passionate and talented fans of the material: the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies are one-reelers, seven to eight minutes of concentrated gag-based comedy that routinely made a joke about how much they weren't functional narratives. It is not impossible to make an entire feature-length film that's a mostly plotless collection of gags, and have it work: Jacques Tati made at least three out-and-out masterpieces that way, and one of those is in excess of two hours. But, I mean, he's French. Dante and Doyle certainly meant well, and their energy in constructing gag after gag after gag until Back in Action has finally landed at 93 minutes, with credits, is unflagging. But it's a long time to go without a break, and the scrawny little doodle of a narrative lashing everything together somehow feels all the scrawnier for being asked to stand up for that length of time.

The rest of the problems are all localised, a matter of individual gags and routines that just don't play the way the filmmakers wanted them to. Which is really the only problem a film like this could have, given that it is at heart nothing but a long chain of gags, sometimes with only the most cursory transition between them. I will say this, at least: the failures of Back in Action tend to be large and fearless failures. Such as Steve Martin's performance as the villain, chairman of the ACME Company, who is trying to find a magical monkey statue that can turn all of humanity into monkeys, so he can have them manufacture an infinite number of shoddy goods at the ACME factory, whereupon he will turn them back into humans, and sell them the shoddy goods he has thus stockpiled. Tasked with playing a live-action cartoon, Martin holds nothing back whatsoever, flinging his body around like a ragdoll (indeed, one of the running gags is that his movements tend to make him almost, but not quite, fall over backawards), swallowing his lips, disappearing into his incredibly awful wig and giant glasses, and delivering every line with a bellowing melodramatic purr. It is a lot of acting, and good for him; I am tempted to say it never works. The single best part of Martin's entire performance, wincing offscreen as he hears Wile E. Coyote crashing into obstacles, is also the smallest and most subdued, though only in this context would Martin's exaggerated rubber-faced reaction shots count as "subdued". But he went for it, bless him.

My lord, that's a whole lot of pissing on a movie that I genuinely love. This is partially because it's easier to identify the flaws in Back in Action; the successes are much more about a freestanding mood it creates, one that the individual viewer either clicks with, or doesn't. Dante's main job as a filmmaker has been to clear the way for lots of very elaborate silliness to spin out, verbally and visually, at extraordinary cost to Warner Bros. Back in Action is a thunderously elaborate movie, an endless line of ludicrously overdesigned spaces full of visual gags. The most inspired of this is Area 52, overseen by the pleasant mad scientist Mother (Joan Cusack, whose twitchy cartoon energy works in all the ways that Martin's, for whatever reason, doesn't; it's reminiscent of what she did in Toys, only better. Or, at least, this movie knows better what to do with her); it's a jam-packed room full of all the B-movie references a legendary B-movie nerd like Dante can cram into one space, with a Triffid and a Metaluna mutant and a Dalek and God knows what all shoving their way into one generously busy widescreen frame. But even in more generic locations - the Warner studio office, a movie star's mansion in Hollywood - there's a sense of exaggerated movie-movie bigness in the giant imposing glass walls of the office, or the trapped-in-the-1920s lines and furniture in the mansion.

And then there's the verbal humor, full of wordplay and deadpan metajokes; the whole plot, once you shake out the Bondian supervillain part, is basically about how dumb Warner Bros. would be to try to make a feature film version of the Looney Tunes, and how lifelessly mercenary the decision-making processes in the film industry are, with their soul-sucking focus on brand extensions and marketing-friendly creative decisions. The film's antihero, who turns eventually into a co-protagonist, is a development executive played by Jenna Elfman, committing hard to being as plastic and unamusing as possible until that turn happens. None of this feels like it rises up to the level of satire, really, nor any serious attempt to bite at Warners; it's more just the same jolly absurd nonsense as all the rest of the jokes, a 21st Century freshening-up of the old Tex Avery "I do this to him through the whole picture" kind of self-referential gag where everybody onscreen knows that it's a movie made for crassly commercial reasons, but since we all know that, we can still go about the business of having fun and not pretending like we're dealing with anything to be taken seriously. And that really is the vibe of the whole film, ably carried out by Dante and shouldered by actual protagonist Brendan Fraser, whose bland "cheap movie star" good looks are perfect for this role, and whose comic timing turns out to be one of the film's best strengths, especially his ability to shoot glances right into the camera without going all the way to mugging or pulling faces. He's also, by a fair margin, the best human in the cast at interacting with the spaces where animated characters are to be plugged in later.

And that gets us to the most important part of all, which is of course the Looney Tunes part of Looney Tunes: Back in Action. Speaking as a diehard fan of the short film series, which I have numerous times suggested is the most important American contribution to the art form of cinema, I am very happy with what these other diehard fans have given me. You have to go all the way back to the 1950s and the last years of the Golden Age of Hollywood short film animation to find another project that cares so very much for these characters, for the specific breed of comedy that they were used to create, and for their wonderfully expressive designs. Bringing Goldberg on to direct the animation was one of the best decisions that ever got made in the production of the film; he was the closest thing Disney had to a Warner-style animator, and his work supervising the Genie in Aladdin, a character of physically unstable lines and a tendency towards exaggerated caricature, was the closest that studio ever got to the kind of work that was the foundation of classic-era Looney Tunes. So on the one hand, we have a man who knows the material, maybe as well as anybody working in animation in the early 2000s did. And on the other hand, we have a man who honed his talents working in a studio that turned the most elaborate, technically complex animation that had ever existed.

Both of these threads combine in Back in Action, whose visual style is primarily built around answering the question, "what if the Looney Tunes characters actually existed in the three-dimensional world of humans?" One of the most noticeable things about this film: the camera is restless as hell. Tracking shots abound, moments where it rotates around the action in a half-circle are only a bit less common, and the feeling one gets is of constant, almost nervous movement. As much as anything else, the purpose of this seems to be just to prove that they could do it: convincingly placing two-dimensional drawings into a three-dimensional space is already a technical feat, but adding constant camera movement to it makes it the kind of unnecessarily difficult task that only makes sense if e.g. Warner Bros. has given you $80 million and you are not very concerned with making sure that they get it back. That, coupled with the extremely detailed shading Goldberg applies to the characters to make them feel like three-dimensional figures interacting with real-world light sources puts Back in Action second to only 1988's masterpiece-level Who Framed Roger Rabbit in all the decades of hybridising hand-drawn animation with live-action footage.

None of which would matter if they weren't the Looney Tunes, executed with reverence and enthusiasm by filmmakers and animators who are palpably delighted to be making new old-fashioned slapstick cartoons. At times, the film errs on the side of too much awestruck fannish glee; for example, the opening is a fairly direct remake of the cartoons of the iconic Hunting Trilogy, done with much more technical panache, and it is firstly the case that the panache does it no good. It is secondly the case that there's a certain airlessness to the re-enactment of old gags, and Back in Action never does entirely shake off a slight feeling of ritualism, a feeling that we must very lovingly worship these characters, and not just laugh at them. Not great for the characters, not great for the jokes, which are sometimes more "I appreciate the structure of that joke" funny and less actually funny. But pretty much always great for the animation, at least, which has a vigorous squashy, stretchy quality that isn't really seen anywhere else in 21st Century theatrical animation - nor in 20th Century animation for a good 40 years before it was made, for that matter. It's a soppy love letter to what was in 2003 and is still a dead art form, and as someone who considers it to be one of the most important art forms in the history of the cinema, I find it all very winning and contenting and delightful, no matter how imperfect.