Shoot that poison arrow to my heart

A review requested by Gavin, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Saint Sebastian, who according to tradition died a martyr in 288 (he was clubbed to death, having miraculously recovered from being shot full of arrows), is officially the patron saint of soldiers, athletes, people with the plague, and persecuted Christians. Unofficially and anecdotally, he is also the patron saint of Catholic artists looking to depict a gorgeous, mostly-naked young man writing in rapturous pain as rigid arrows penetrate his body all over his flawlessly carved abdomen. Indeed, there is a line of thought that the most lovingly-rendered portraits of Sebastian made him the very first gay icon, with out and less-out gay men since at least the 19th Century gravitating towards imagery of Sebastian as a sort of rallying point for exploring the intersection of faith, suffering, and homoerotic desire.

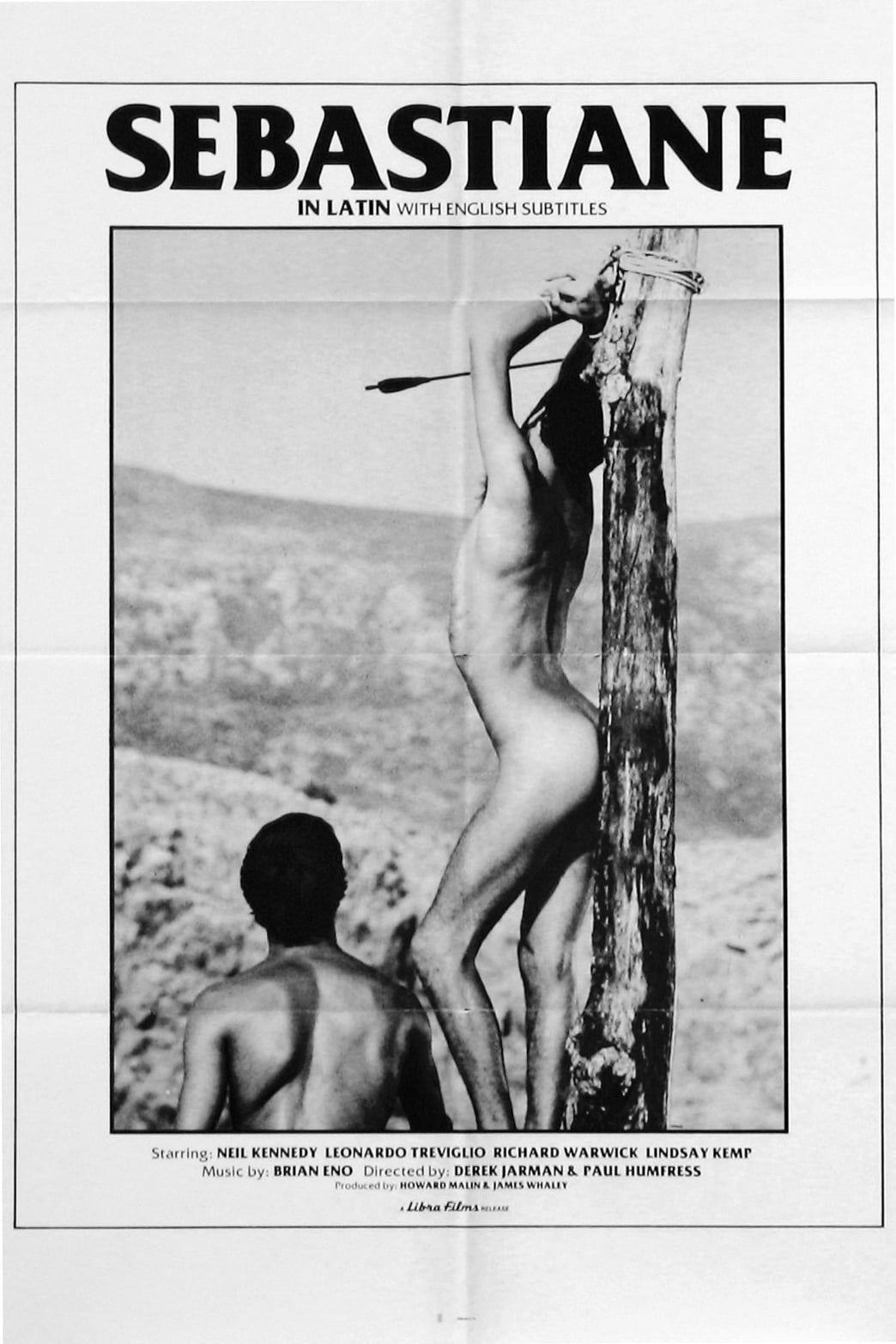

Given this, it's not surprising at all that the rise of gay underground cinema in the 1960s and 1970s led to the making of a feature film about Sebastian. It may indeed be more surprising that there was only one, though I suppose the answer there is that, in the wake of Derek Jarman and Paul Humfress's 1976 Sebastiane, it's hard to imagine what more there could possibly be to do with the subject. Given where Jarman's career would go following this, his first narrative feature (it was Humfress's debut as well, though he didn't do anything afterwards) after some experimental shorts, it's no surprise that he mined the material pretty thoroughly, enough so that I cannot imagine being the filmmaker who would decide to see what might possibly be left to say. They had the script translated in Latin, for God's sake. Vulgar Latin no less, which didn't even leave behind a written form.

Sebastiane possesses only the thinnest wisp of a plot: Sebastian (Leonard Treviglio) is a favorite of Emperor Diocletian (Robert Medley), in whose personal guard he serves; but Diocletian is in a paranoid mood these days, seeing Christians around every corner, and when he thinks Sebastian might be one, the guard is busted down to serve in an unremarkable garrison in some rocky patch of nowhere between the desert and the sea. Here, the air crackles with erotic yearning, as the men lounge about wearing scrawny cloth jockstraps and practically nothing else, except for the commander Severus (Barney James), a bored petty tyrant. Men splash in the water and bathe, they sleep wherever the glaring sun can't reach, and above all else, they watch each other's bodies as they sweat and flex and catch the light.

Watching is the heart and soul of Sebastiane. The film is pure scopophilia, all about the eroticism of visual pleasure and looking at bodies; this is what the characters do, and this is what Peter Middleton's camera does. Jarman and Humfress seem to be drawing a very hard distinction between this kind of eroticism and actual sex; there's only one point in the entire film where two men, Anthony (Janusz Romanov) and Adrian (Ken Hicks), even kiss, and this is pointedly and coldly interrupted by Severus. Instead, Sebastiane is fixated on gazing at its subjects, rendering them not so much sexual humans as visual objects to appreciate; given Sebastian's outsized historical importance in the annals of gay iconography, this feels like the most appropriate way, maybe even the only appropriate way to place him into a movie.

This oddly bloodless, intellectual horniness - Sebastiane is unabashedly fond of looking at nude males without being, like, turned on by nude males - is one of the film's two major strands. The other is in a sense its exact opposite, a completely non-intellectual dive into sex and physical desire as a kind of spiritually ecstatic condition. Which is also a crucial part of Sebastian's iconography, given the tradition of depicting him with a look of rapture as he's being shot through with arrows. And there's definitely a spirit of sexual masochism underpinning the film's depictions of the corporal punishment inherent to life in a Roman garrison, lingering on the streaks of blood that spring up on whipped backs and the stretched-out limbs of a man being hung by his arms. But some of this spiritualism comes simply in the form of the film's beautifully dreamlike aesthetic. The film's compositions, in the pleasingly square-shaped 1.37:1 aspect ratio, are perfect at framing full-length bodies in groups, or as diagonally-oriented shapes laid across rocks, or curled up in pools and tubs splashing about; without borrowing from the martyr paintings of St. Sebastian themselves, the film has fallen into a painterly style where the human bodies seem to meld into the rocky, scrubby landscape. It's a way to render the naked and mostly-naked bodies we see as fully aesthetic objects, and to create a slight sense of mythic, otherworldly remoteness. Sebastiane has an almost abstract look, pushing us away from the here-and-now of its scenes, and that feeling is much amplified by a terrific Brian Eno score, full of long electronic notes that drone out slowly and hold themselves in the air, transforming the ancient feeling of the setting into something outright hallucinatory by tethering it to sounds that are futuristic to the point of barely feeling earthbound.

That cinematography and that music, taken together, are most of what Sebastiane needs to spend much of its time in a state of trancelike remove. And that state is exactly what the film needs to make its languid, lusty shots of male bodies drift into something that feels like an actual expression of transporting ecstasy, appreciating nudity and the fleshiness of bodies so much that it actually transmutes into a kind of worship. And this is a third thing that, well, of course an adaptation of the martyrdom of Sebastian would need to be about. Particularly when we arrive at the execution itself, in which the penetration of arrows is achieved with an artful detachment, culminating in a final shot that breaks out the film's first and only wide-angle lens, exactly the right choice to transform the act of suffering into a vision of otherworldly detachment.

Grounding all of this, the film does also have a crude earthiness about it. It starts out with a gesture that pins this down, with Diocletian's court enjoying a ludicrous pantomime of a gay orgy in which men with giant multi-colored phalluses strapped on their bodies balletically thrust at a man painted all in white, with a garish clown face; it's jarringly modern, with the white man's make-up feeling obviously indebted to glam rock and drag, and this anchors it to the queer avant-garde cinema of the day; it's also the most brutish and crude depiction of sex in the film, which is part of the joke, and part of the seriousness, as the very first thing the movie ever does is to anchor sex in the bluntly carnal, while the rest of the movie drifts into wispy dreamscapes of granite abdomens in half light.

Mostly, though, the film relies on its acting to keep it feeling fleshy and coarse. Simply put, the cast isn't great, and dealing with vulgar Latin means that most of them are doing everything they can just to recite the dialogue. And so, instead of the theatrical figures who often show up in Roman-set films, we end up getting a bunch of, frankly, gay bros: fairly crude guys hanging out and talking in kind of slangy, low-energy ways, doing nothing at all to imbue the scenario with any feeling of urgency or weight. They're just a bunch of naked guys tormenting each other, sometimes as a way of flirting with each other, sometimes because playfully attacking each other is just what dudes do. And the particular artless dudes populating Sebastiane do a whole lot to turn a very intellectual exercise into something that feels satisfyingly grounded in everyday libido and physicality.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Saint Sebastian, who according to tradition died a martyr in 288 (he was clubbed to death, having miraculously recovered from being shot full of arrows), is officially the patron saint of soldiers, athletes, people with the plague, and persecuted Christians. Unofficially and anecdotally, he is also the patron saint of Catholic artists looking to depict a gorgeous, mostly-naked young man writing in rapturous pain as rigid arrows penetrate his body all over his flawlessly carved abdomen. Indeed, there is a line of thought that the most lovingly-rendered portraits of Sebastian made him the very first gay icon, with out and less-out gay men since at least the 19th Century gravitating towards imagery of Sebastian as a sort of rallying point for exploring the intersection of faith, suffering, and homoerotic desire.

Given this, it's not surprising at all that the rise of gay underground cinema in the 1960s and 1970s led to the making of a feature film about Sebastian. It may indeed be more surprising that there was only one, though I suppose the answer there is that, in the wake of Derek Jarman and Paul Humfress's 1976 Sebastiane, it's hard to imagine what more there could possibly be to do with the subject. Given where Jarman's career would go following this, his first narrative feature (it was Humfress's debut as well, though he didn't do anything afterwards) after some experimental shorts, it's no surprise that he mined the material pretty thoroughly, enough so that I cannot imagine being the filmmaker who would decide to see what might possibly be left to say. They had the script translated in Latin, for God's sake. Vulgar Latin no less, which didn't even leave behind a written form.

Sebastiane possesses only the thinnest wisp of a plot: Sebastian (Leonard Treviglio) is a favorite of Emperor Diocletian (Robert Medley), in whose personal guard he serves; but Diocletian is in a paranoid mood these days, seeing Christians around every corner, and when he thinks Sebastian might be one, the guard is busted down to serve in an unremarkable garrison in some rocky patch of nowhere between the desert and the sea. Here, the air crackles with erotic yearning, as the men lounge about wearing scrawny cloth jockstraps and practically nothing else, except for the commander Severus (Barney James), a bored petty tyrant. Men splash in the water and bathe, they sleep wherever the glaring sun can't reach, and above all else, they watch each other's bodies as they sweat and flex and catch the light.

Watching is the heart and soul of Sebastiane. The film is pure scopophilia, all about the eroticism of visual pleasure and looking at bodies; this is what the characters do, and this is what Peter Middleton's camera does. Jarman and Humfress seem to be drawing a very hard distinction between this kind of eroticism and actual sex; there's only one point in the entire film where two men, Anthony (Janusz Romanov) and Adrian (Ken Hicks), even kiss, and this is pointedly and coldly interrupted by Severus. Instead, Sebastiane is fixated on gazing at its subjects, rendering them not so much sexual humans as visual objects to appreciate; given Sebastian's outsized historical importance in the annals of gay iconography, this feels like the most appropriate way, maybe even the only appropriate way to place him into a movie.

This oddly bloodless, intellectual horniness - Sebastiane is unabashedly fond of looking at nude males without being, like, turned on by nude males - is one of the film's two major strands. The other is in a sense its exact opposite, a completely non-intellectual dive into sex and physical desire as a kind of spiritually ecstatic condition. Which is also a crucial part of Sebastian's iconography, given the tradition of depicting him with a look of rapture as he's being shot through with arrows. And there's definitely a spirit of sexual masochism underpinning the film's depictions of the corporal punishment inherent to life in a Roman garrison, lingering on the streaks of blood that spring up on whipped backs and the stretched-out limbs of a man being hung by his arms. But some of this spiritualism comes simply in the form of the film's beautifully dreamlike aesthetic. The film's compositions, in the pleasingly square-shaped 1.37:1 aspect ratio, are perfect at framing full-length bodies in groups, or as diagonally-oriented shapes laid across rocks, or curled up in pools and tubs splashing about; without borrowing from the martyr paintings of St. Sebastian themselves, the film has fallen into a painterly style where the human bodies seem to meld into the rocky, scrubby landscape. It's a way to render the naked and mostly-naked bodies we see as fully aesthetic objects, and to create a slight sense of mythic, otherworldly remoteness. Sebastiane has an almost abstract look, pushing us away from the here-and-now of its scenes, and that feeling is much amplified by a terrific Brian Eno score, full of long electronic notes that drone out slowly and hold themselves in the air, transforming the ancient feeling of the setting into something outright hallucinatory by tethering it to sounds that are futuristic to the point of barely feeling earthbound.

That cinematography and that music, taken together, are most of what Sebastiane needs to spend much of its time in a state of trancelike remove. And that state is exactly what the film needs to make its languid, lusty shots of male bodies drift into something that feels like an actual expression of transporting ecstasy, appreciating nudity and the fleshiness of bodies so much that it actually transmutes into a kind of worship. And this is a third thing that, well, of course an adaptation of the martyrdom of Sebastian would need to be about. Particularly when we arrive at the execution itself, in which the penetration of arrows is achieved with an artful detachment, culminating in a final shot that breaks out the film's first and only wide-angle lens, exactly the right choice to transform the act of suffering into a vision of otherworldly detachment.

Grounding all of this, the film does also have a crude earthiness about it. It starts out with a gesture that pins this down, with Diocletian's court enjoying a ludicrous pantomime of a gay orgy in which men with giant multi-colored phalluses strapped on their bodies balletically thrust at a man painted all in white, with a garish clown face; it's jarringly modern, with the white man's make-up feeling obviously indebted to glam rock and drag, and this anchors it to the queer avant-garde cinema of the day; it's also the most brutish and crude depiction of sex in the film, which is part of the joke, and part of the seriousness, as the very first thing the movie ever does is to anchor sex in the bluntly carnal, while the rest of the movie drifts into wispy dreamscapes of granite abdomens in half light.

Mostly, though, the film relies on its acting to keep it feeling fleshy and coarse. Simply put, the cast isn't great, and dealing with vulgar Latin means that most of them are doing everything they can just to recite the dialogue. And so, instead of the theatrical figures who often show up in Roman-set films, we end up getting a bunch of, frankly, gay bros: fairly crude guys hanging out and talking in kind of slangy, low-energy ways, doing nothing at all to imbue the scenario with any feeling of urgency or weight. They're just a bunch of naked guys tormenting each other, sometimes as a way of flirting with each other, sometimes because playfully attacking each other is just what dudes do. And the particular artless dudes populating Sebastiane do a whole lot to turn a very intellectual exercise into something that feels satisfyingly grounded in everyday libido and physicality.