Canada is just one failed orgasm after another

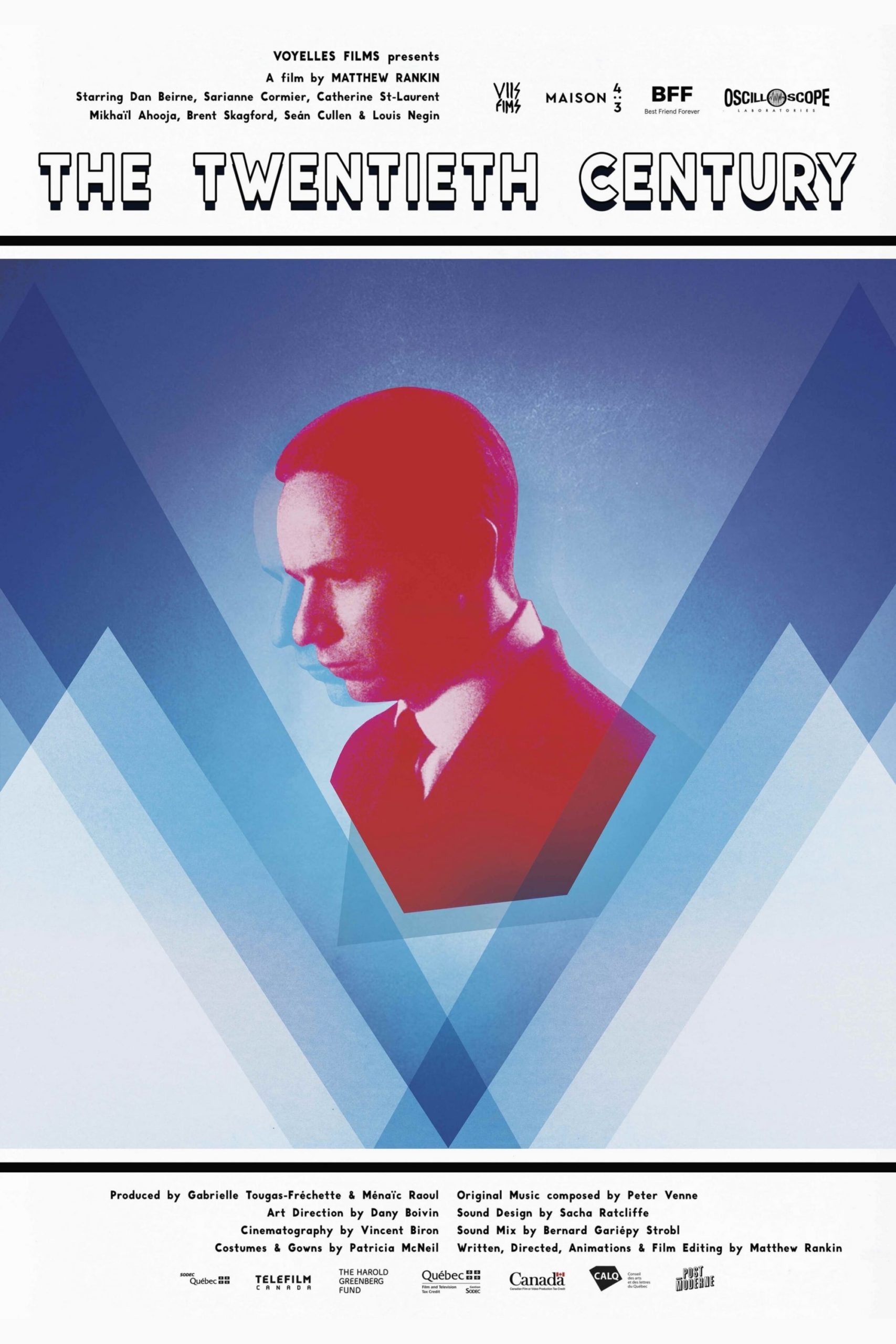

Probably the simplest way to start explaining what the living hell we have in front of us with The Twentieth Century, the first feature-length film by avant-garde director Matthew Rankin (who had some fairly substantial attention, by the standards of such things, with the shorts Mynarski Death Plummet in 2014 and The Tesla World Light in 2017), is that the only thing it even slightly resembles is the work of Guy Maddin. To wit: it's a Canadian film, and it's also very firmly about Canada and its history, in a way that's frankly pretty impenetrable for a non-Canadian like myself to appreciate in all its nuances, which center on the relationship between Manitoba and the rest of the country (Rankin, unlike Maddin, is particularly fixated on Québec, though this isn't present much in The Twentieth Century). The most obvious element of the film's style is a pastiche of silent cinematic forms - here, the blatantly artificial theatrical flats of German Expressionism that feel less like "set" per se, and more like abstract geometric shapes that sort of loosely imply the existence of an environment without actually defining it - and crapped-up cinematography designed to make it look like it was stored in a damp attic for the last 90 years; the second most obvious element is borrowing liberally from the long history of the queer avant-garde, though The Twentieth Century goes much farther with this than anything Maddin has ever gotten up to.

It's also much more blatantly and aggressively political, enough that it probably qualifies as satire, though pretending that The Twentieth Century is doing anything plainly enough to have a clear message it wants the viewer to walk away with would be pushing it. It is, in fact, kind of a political biopic, albeit one in which nearly all of the details have been invented from whole cloth. The central figure in the film is William Lyon Mackenzie King (Dan Beirne), a member of the Liberal Party who served three nonconsecutive terms as Prime Minister, two of them directly following Arthur Meighen (Brent Skagford), who also shows up in the movie, as King's chief political enemy (this is about as close as it comes to an actual historical fact. The film takes place in 1899, when King was 24, and not yet involved in politics in reality; in the movie, he, Meighen, and Bert Harper (Mikhail Ahooja) are in brutal conflict of who will serve as Prime Minister under Governor General Lord Muto (Seán Cullen), a fascist madman hoping to drag Canada into the heart of the Boer War. King's political ambitions are complicated by a his very disarrayed personal life: he has lately seen a woman, Ruby (Catherine St-Laurent), who looks precisely like vision he has been having for some time, and is convinced that she is fated to be his wife. The fact that she turns out to be Lord Muto's daughter and Harper's fiancée is quite a wrinkle to this destiny; so is King's very tendentious relationship with his own sex drive, which involves at very least a fetish for huffing smelly old shoes, and has a very complicated homoerotic dimension, manifested in the film's love of cross-gender casting different characters with whom King has thorny psychosexual relationships (both men and women), most significantly including regular Maddin collaborator Louis Negin as King's mother. It's a terrific weaponisation of camp that restores some of the dangerous luster of midcentury queer experimental cinema as something that can actually threaten and destabilise the extreme, insistent "normality" that King desperately wants to exude.

It's a weird film in that it feels at once both exorbitantly kinky and horny (at one point a cactus in King's bedroom explodes in a clotted, pasty bone-white goo as he's feverishly pressing a stolen boot to his face) while abstracting everything about its world, characters, and story to a degree that everything feels stripped of actual emotional content or humanity - or sexuality. It is a masque, a pantomime, a kind of Canuck kabuki that presents itself to us as heavily ironised gestures; there's nothing real about it. But in the best Expressionist tradition (and I do think that if you're going to make anything out of the movie whatsoever, you need to start by assuming that it is legitimately Expressionist, and not just a pastiche of Expressionist aesthetics), the unreality is pointing towards something deeply true.

At heart, the film is using excess to attack milquetoast politicians for whom the acquisition of power is the point, rather than doing anything with. Poor William Lyon Mackenzie King is a perfect fit for Rankin's savagery, because of his historical status: if I understand correctly (and any Canadian readers are welcome to correct me), King is among the most highly-regarded of all Prime Ministers largely on the basis of being inoffensive to pretty much any tastes, and he's inoffensive because he tried to do almost nothing other than maintain things the way they were going. Certainly, the film's King bears that understanding out, presenting King as a feckless little nobody, played immaculately by Beirne as a whinging neurotic with a desperately sweaty fake smile that he forcibly pretend is "charismatic", devoid of an inner life and in a constant state of panic that he needs to fake having one. It's a supremely loathsome characteristaion, done perfectly, and hilariously, building a portrait of the deeply neutral politician as a lonely, sad figure who can't know himself, and who turns that lack of self-knowledge into something devastating and cruel to the world at large,. And if the points it makes about the acquisition of political power are relatively blunt (you don't say, all of them are jerks? Very interesting), they're presented with such giddy energy through the minimalist fascist apocalyptic visuals that it feels exciting and new regardless.

That is, after all, the point of this all: The Twentieth Century is a big ol' wacky comedy, using its horrifying Expressionist excesses to facilitate a whole series of great jokes about the petty little vulgarities of politicians trying to expunge their humanity, or just Canada itself. The qualifications for becoming Prime Minister include being excellent at demonstrating passive-aggressive annoyance with people cutting in line, or identifying different evergreen trees in a blindfolded smell test, for example. Also being able to create the bloodiest mess while clubbing baby seals. So even in the most genial absurdity, there's still a harsh, angry edge, and that's what makes The Twentieth Century more than just a skilled Maddin homage. And even at the surface level, it goes in different directions than Maddin, bringing in a wild '80s sci-fi world in the final stretch to make its vision of Canada as little cardboard props and forced perspective landscapes even more otherworldly. The whole thing adds up to a pretty fine argument that the same 20th Century that's at stake in the film's conflict is just the creation of petty little madmen and hallucinatory sex freaks, presenting this caustic worldview through a beautifully ugly time capsule from an imaginary past that's mythic in the smallest, shabbiest way. Rankin has some kind of genuinely singular vision on display here, a nightmarish absurdist comedy that's full of good cheer and whimsical silliness even as it presents an almost unendurably cynical understanding of civilisation. To love this film, one must love it all the way, and I do, but it's a whole lot to take in.

It's also much more blatantly and aggressively political, enough that it probably qualifies as satire, though pretending that The Twentieth Century is doing anything plainly enough to have a clear message it wants the viewer to walk away with would be pushing it. It is, in fact, kind of a political biopic, albeit one in which nearly all of the details have been invented from whole cloth. The central figure in the film is William Lyon Mackenzie King (Dan Beirne), a member of the Liberal Party who served three nonconsecutive terms as Prime Minister, two of them directly following Arthur Meighen (Brent Skagford), who also shows up in the movie, as King's chief political enemy (this is about as close as it comes to an actual historical fact. The film takes place in 1899, when King was 24, and not yet involved in politics in reality; in the movie, he, Meighen, and Bert Harper (Mikhail Ahooja) are in brutal conflict of who will serve as Prime Minister under Governor General Lord Muto (Seán Cullen), a fascist madman hoping to drag Canada into the heart of the Boer War. King's political ambitions are complicated by a his very disarrayed personal life: he has lately seen a woman, Ruby (Catherine St-Laurent), who looks precisely like vision he has been having for some time, and is convinced that she is fated to be his wife. The fact that she turns out to be Lord Muto's daughter and Harper's fiancée is quite a wrinkle to this destiny; so is King's very tendentious relationship with his own sex drive, which involves at very least a fetish for huffing smelly old shoes, and has a very complicated homoerotic dimension, manifested in the film's love of cross-gender casting different characters with whom King has thorny psychosexual relationships (both men and women), most significantly including regular Maddin collaborator Louis Negin as King's mother. It's a terrific weaponisation of camp that restores some of the dangerous luster of midcentury queer experimental cinema as something that can actually threaten and destabilise the extreme, insistent "normality" that King desperately wants to exude.

It's a weird film in that it feels at once both exorbitantly kinky and horny (at one point a cactus in King's bedroom explodes in a clotted, pasty bone-white goo as he's feverishly pressing a stolen boot to his face) while abstracting everything about its world, characters, and story to a degree that everything feels stripped of actual emotional content or humanity - or sexuality. It is a masque, a pantomime, a kind of Canuck kabuki that presents itself to us as heavily ironised gestures; there's nothing real about it. But in the best Expressionist tradition (and I do think that if you're going to make anything out of the movie whatsoever, you need to start by assuming that it is legitimately Expressionist, and not just a pastiche of Expressionist aesthetics), the unreality is pointing towards something deeply true.

At heart, the film is using excess to attack milquetoast politicians for whom the acquisition of power is the point, rather than doing anything with. Poor William Lyon Mackenzie King is a perfect fit for Rankin's savagery, because of his historical status: if I understand correctly (and any Canadian readers are welcome to correct me), King is among the most highly-regarded of all Prime Ministers largely on the basis of being inoffensive to pretty much any tastes, and he's inoffensive because he tried to do almost nothing other than maintain things the way they were going. Certainly, the film's King bears that understanding out, presenting King as a feckless little nobody, played immaculately by Beirne as a whinging neurotic with a desperately sweaty fake smile that he forcibly pretend is "charismatic", devoid of an inner life and in a constant state of panic that he needs to fake having one. It's a supremely loathsome characteristaion, done perfectly, and hilariously, building a portrait of the deeply neutral politician as a lonely, sad figure who can't know himself, and who turns that lack of self-knowledge into something devastating and cruel to the world at large,. And if the points it makes about the acquisition of political power are relatively blunt (you don't say, all of them are jerks? Very interesting), they're presented with such giddy energy through the minimalist fascist apocalyptic visuals that it feels exciting and new regardless.

That is, after all, the point of this all: The Twentieth Century is a big ol' wacky comedy, using its horrifying Expressionist excesses to facilitate a whole series of great jokes about the petty little vulgarities of politicians trying to expunge their humanity, or just Canada itself. The qualifications for becoming Prime Minister include being excellent at demonstrating passive-aggressive annoyance with people cutting in line, or identifying different evergreen trees in a blindfolded smell test, for example. Also being able to create the bloodiest mess while clubbing baby seals. So even in the most genial absurdity, there's still a harsh, angry edge, and that's what makes The Twentieth Century more than just a skilled Maddin homage. And even at the surface level, it goes in different directions than Maddin, bringing in a wild '80s sci-fi world in the final stretch to make its vision of Canada as little cardboard props and forced perspective landscapes even more otherworldly. The whole thing adds up to a pretty fine argument that the same 20th Century that's at stake in the film's conflict is just the creation of petty little madmen and hallucinatory sex freaks, presenting this caustic worldview through a beautifully ugly time capsule from an imaginary past that's mythic in the smallest, shabbiest way. Rankin has some kind of genuinely singular vision on display here, a nightmarish absurdist comedy that's full of good cheer and whimsical silliness even as it presents an almost unendurably cynical understanding of civilisation. To love this film, one must love it all the way, and I do, but it's a whole lot to take in.