Never enough time

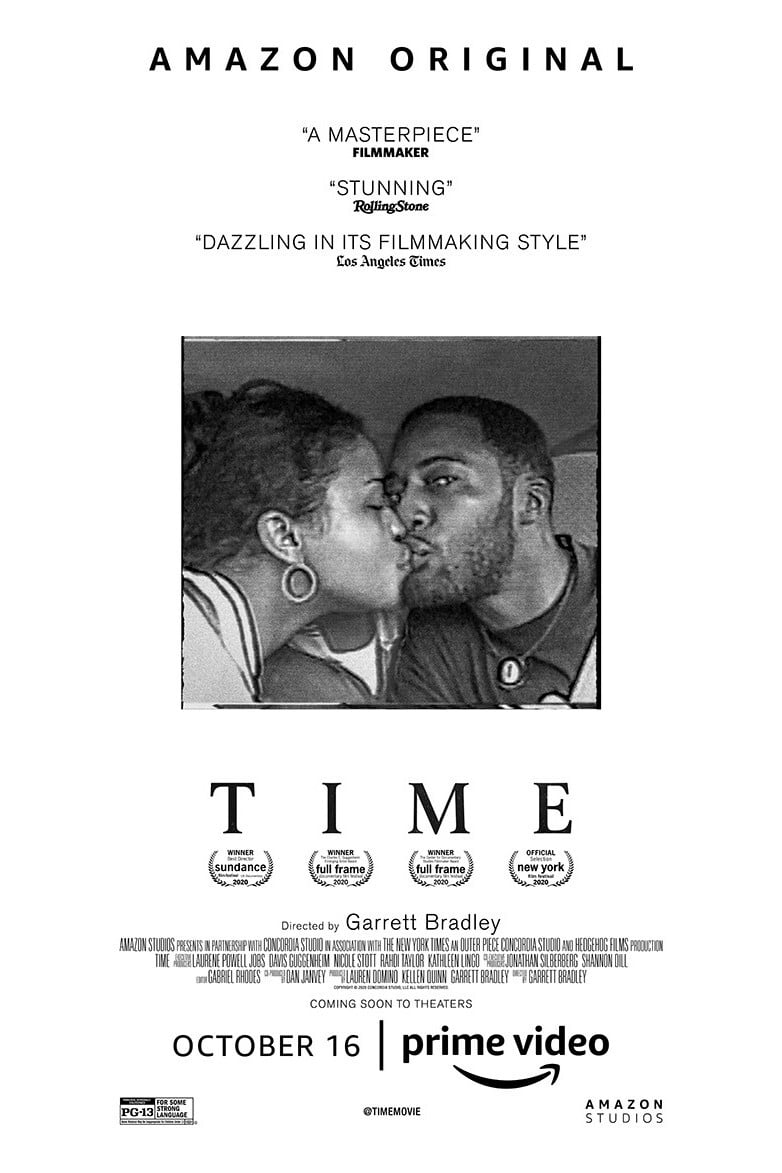

It's an uncharitable thing to say about such a passionate work of cinema-activism, but there was not one moment in the 81 minutes of Time, a documentary about the excesses of the U.S. prison system and how it affected one family over the course of 20 years, where I could shake the feeling that I was being sold something. This has, I am certain, almost everything to do with director Garrett Bradley's very strange and distracting and inexplicable decision to present the entire film in glossy fashion-magazine black-and-white, creating a very tinny digital sheen that makes the whole movie feel bizarrely and incongruously glamorous, and for no reason that I can come even slightly close to sussing out. Because black-and-white "equals" nostalgia and the past, I guess, but the mixture of different digital formats would surely do that just as well without giving the whole movie the unlikable flavor of a perfume ad.

The film relies extensively on archival video footage mixed in, unremarked, with brand new footage, creating a slurry of two decades blurring together into one single, unendurable present-tense moment; I suppose at least some of the idea was that transferring everything to black-and-white would make it a little bit harder to tell when one era fades into the other. If that's the case, it doesn't work - the shift in resolution is too obvious for any amount of post-production tinkering to disguise it - and even if it did work, I'm not sure it would have been the right call. One of the foremost strengths of Time lies in how it complicates the relationship between past and present and memories, and the shock of diving into that grotty, ugly old footage from the clean digital crispness of the new footage is one of the single best tools the film has for making us feel the sheer violence of those 20 years, a rupture whose obviousness is right there in the unbridgeable gulf between 1080p and 480i.

The pity of all this is that the idea of Time is extraordinarily good, and in the moments when the film is able to execute that idea to the fullest, it's the equal to any other piece of nonfiction filmmaking from 2020. And this happens most thrillingly as literally the very end of the movie, so I can't even tell you about it, except that it's where director Garrett Bradley most vividly realises the central aesthetic conceit of her project, the idea that manipulating old video footage becomes a way of manipulating time and memory, while also calling our attention to the time that has passed since the video was recorded. It's a gambit that both tries to erase the passage of 20 years while establishing more clearly than anything else in the movie how unendurably long those 20 years were and how they represent an ellipsis in the life of a family that is not ever going to be filled.

The film is, to narrow our focus down from the theoretical, about the 18-year work of Sibil Fox Richardson, a New Orleans activist, public speaker, and businesswoman who also goes by the name Fox Rich (which I presume to be a kind of activist nom de guerre, but the film doesn't really go into it - in general, clarifying context is not among the film's strengths at any turn). In 1997, at the end of their rope and in a panic, Richardson and her husband Rob robbed a bank; she took a plea deal for a three-year sentence, he went to trial and for his trouble was given 60 years in prison. Between the delivery of that sentence and 2018, Fox devoted herself to getting his sentence reduced, while simultaneously raising their six children. We arrive during a particularly promising and also particularly tense stage in the appeal process.

Inasmuch as Bradley and Fox have positioned Time as a message movie about the excessive incarceration of African-Americans in the Unites States, and I think it's fair to assume this was part of their intention, I don't think that it gets there. Facts and figures are an unmistakable weak spot for the film; compared to something like Ava DuVernay's 13th, which minutely (one might even say, un-cinematically) lays out its data, Time is mounting an exclusively emotional appeal, based in the Richardson family themselves. Specifically, it's basing its argument in footage captured over the course of the family's life, marking the notable absence of Rob from family events, as their kids grow from children to young adults. This is all done very impressionistically, with Bradley never pinning down specific moments in time to specific dates, or specific milestones in Fox's attempts to free Rob, but creating a loose flow of memorialised moments, emotionally colored by the narration always drawing us to what's missing from these everyday domestic scenes. This is a tough thing to keep going even for the 81 minutes that Time lasts, and there are lapses; it frequently has to rely on new footage of Fox discussing her ongoing situation, which is simply less interesting than the contrast between archival moments that are being tied together in a relaxed, intuitive way, flattening this into a pretty routine talking-head movie. And Bradley's artful, almost abstract approach does make it hard to understand exactly what's going on: among the most significant missing elements, the film doesn't every define the Richardsons' children as anything more specific than just "our six boys", figures who exist around Fox and whom we get to see grow up with the ghost of a father, but who never arrive in the film with their own voice, or stake their own emotional claim on the events we're watching.

I'm fairly sure that Time would be stronger if that weren't the case, among other soft spots in the narrative (honestly, I'm not even sure I could tell you who Sibil Fox Richardson herself is in those moments when she's not in front of a camera talking about incarceration). But that would also make it a more pedestrian, everyday kind of documentary, and the whole point of the thing is to be something of an experiment. It's trying to evoke, in its form, a sense of absence and loss, built out through patterns in how it uses archival footage to interrupt Fox's present-day flow of thought. It is, one might say, Bradley's attempt to write a memoir on behalf of the Richardsons, especially in those extraordinary final moments, and its strengths as a family drama at least compensate for its shortcomings elsewhere.

The film relies extensively on archival video footage mixed in, unremarked, with brand new footage, creating a slurry of two decades blurring together into one single, unendurable present-tense moment; I suppose at least some of the idea was that transferring everything to black-and-white would make it a little bit harder to tell when one era fades into the other. If that's the case, it doesn't work - the shift in resolution is too obvious for any amount of post-production tinkering to disguise it - and even if it did work, I'm not sure it would have been the right call. One of the foremost strengths of Time lies in how it complicates the relationship between past and present and memories, and the shock of diving into that grotty, ugly old footage from the clean digital crispness of the new footage is one of the single best tools the film has for making us feel the sheer violence of those 20 years, a rupture whose obviousness is right there in the unbridgeable gulf between 1080p and 480i.

The pity of all this is that the idea of Time is extraordinarily good, and in the moments when the film is able to execute that idea to the fullest, it's the equal to any other piece of nonfiction filmmaking from 2020. And this happens most thrillingly as literally the very end of the movie, so I can't even tell you about it, except that it's where director Garrett Bradley most vividly realises the central aesthetic conceit of her project, the idea that manipulating old video footage becomes a way of manipulating time and memory, while also calling our attention to the time that has passed since the video was recorded. It's a gambit that both tries to erase the passage of 20 years while establishing more clearly than anything else in the movie how unendurably long those 20 years were and how they represent an ellipsis in the life of a family that is not ever going to be filled.

The film is, to narrow our focus down from the theoretical, about the 18-year work of Sibil Fox Richardson, a New Orleans activist, public speaker, and businesswoman who also goes by the name Fox Rich (which I presume to be a kind of activist nom de guerre, but the film doesn't really go into it - in general, clarifying context is not among the film's strengths at any turn). In 1997, at the end of their rope and in a panic, Richardson and her husband Rob robbed a bank; she took a plea deal for a three-year sentence, he went to trial and for his trouble was given 60 years in prison. Between the delivery of that sentence and 2018, Fox devoted herself to getting his sentence reduced, while simultaneously raising their six children. We arrive during a particularly promising and also particularly tense stage in the appeal process.

Inasmuch as Bradley and Fox have positioned Time as a message movie about the excessive incarceration of African-Americans in the Unites States, and I think it's fair to assume this was part of their intention, I don't think that it gets there. Facts and figures are an unmistakable weak spot for the film; compared to something like Ava DuVernay's 13th, which minutely (one might even say, un-cinematically) lays out its data, Time is mounting an exclusively emotional appeal, based in the Richardson family themselves. Specifically, it's basing its argument in footage captured over the course of the family's life, marking the notable absence of Rob from family events, as their kids grow from children to young adults. This is all done very impressionistically, with Bradley never pinning down specific moments in time to specific dates, or specific milestones in Fox's attempts to free Rob, but creating a loose flow of memorialised moments, emotionally colored by the narration always drawing us to what's missing from these everyday domestic scenes. This is a tough thing to keep going even for the 81 minutes that Time lasts, and there are lapses; it frequently has to rely on new footage of Fox discussing her ongoing situation, which is simply less interesting than the contrast between archival moments that are being tied together in a relaxed, intuitive way, flattening this into a pretty routine talking-head movie. And Bradley's artful, almost abstract approach does make it hard to understand exactly what's going on: among the most significant missing elements, the film doesn't every define the Richardsons' children as anything more specific than just "our six boys", figures who exist around Fox and whom we get to see grow up with the ghost of a father, but who never arrive in the film with their own voice, or stake their own emotional claim on the events we're watching.

I'm fairly sure that Time would be stronger if that weren't the case, among other soft spots in the narrative (honestly, I'm not even sure I could tell you who Sibil Fox Richardson herself is in those moments when she's not in front of a camera talking about incarceration). But that would also make it a more pedestrian, everyday kind of documentary, and the whole point of the thing is to be something of an experiment. It's trying to evoke, in its form, a sense of absence and loss, built out through patterns in how it uses archival footage to interrupt Fox's present-day flow of thought. It is, one might say, Bradley's attempt to write a memoir on behalf of the Richardsons, especially in those extraordinary final moments, and its strengths as a family drama at least compensate for its shortcomings elsewhere.

Categories: documentaries, fun with structure, message pictures