Skin in the game

The Man Who Sold His Skin is the kind of movie that sounds better when you're hearing about it - or even when you're describing it - than when you're actually in front of it, watching it. If I were to tell you the ideas it was playing with, and how it assembles them all into a unified argument about different kind of oppression, commodification of human bodies, and basic human disrespect, I suspect you would think it was a much tighter, snappier, smarter film than is the case.

Which is different than saying that it's not tight, snappy, or smart, or that I generally disliked it. In fact I generally liked it, quite a bit even, and if not for a stunningly bad ending, contrived and tone-deaf, I would surely feel a lot more openly enthusiastic about the thing. Even at it's best, it's the kind of thing that wants to be celebrated for its cunning, timely satire more than it actually wants to go to the trouble of being cunning, and it generally takes easy swings at safe targets. Exactly the sort of movie that ought to get an Oscar nomination, then, and I am happy for The Man Who Sold His Skin that it has had the good fortune to become its truest self, thereby coming to a level of attention that it absolutely would not have received under any other circumstances.

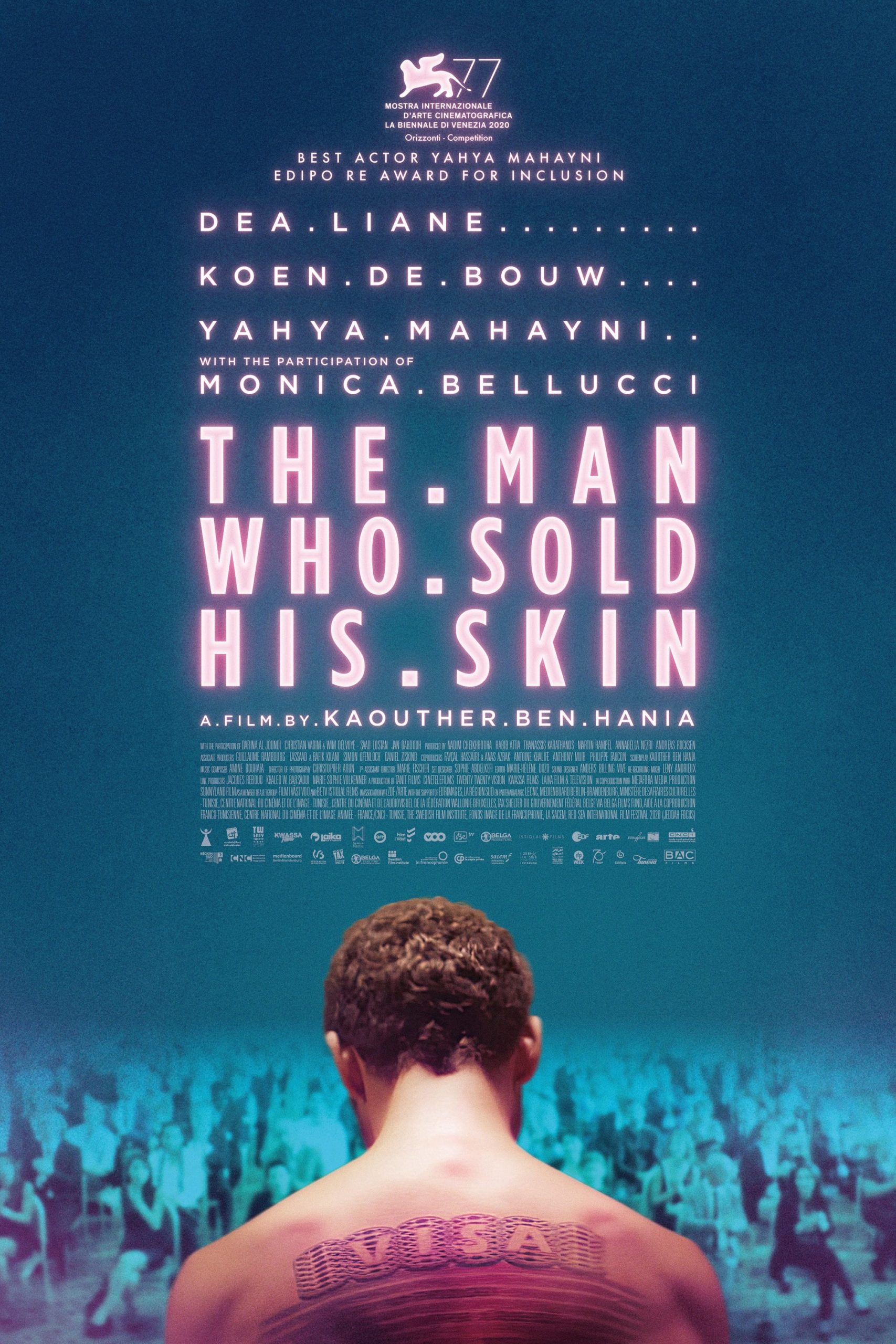

Snark, snark, snark, but in truth, the film has some pretty strong moves, courtesy of director and writer Kaouther Ben Hania. I'm not familiar with her earlier work, which has mostly been in documentaries, and that wouldn't obviously have been the right training ground for the work she's up to here: a slightly arch visual style built around a motif of the camera staying directly behind its subjects' heads, placing them as geometric objects in a brittle world of straight lines and claustrophobically empty rooms. We get one of the boldest examples of this right at the start, in a scene that openly crows about how it's mysteriously disconnected from the rest of the movie: a man we'll later learn is the internationally celebrated artist Jeffrey Godefroy (Koen De Bouw), whose big thing is that he signs his name to everyday objects, thereby rendering them as "art" that sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and he and the people spending the money and the critics praising him for it all openly agree that this is a brilliant indictment of the commercialisation of the art world. In 2011, no less, a mere 90 years or so after that ceased to be a new observation. But to be fair to The Man Who Sold His Skin, if the art world had learned anything in those 90 years, it wouldn't be possible to satirise it on that level. At any rate, when we first meet Godefroy, he's doing none of this, he's just walking through a fearsome space of white floors and white walls with mirrors on seemingly every vertical surface, creating a sense of infinite sterility except when we see his face reflected (we never see it directly). It's the most striking visual moment of the entire movie, which is never exactly what you want from an opening scene, but it anyways gets us off to a good start: in this film, art spaces are geometric boxes of beautifully inhuman hells. Got it.

Shortly thereafter, we meet the man who sold his skin. Or soon will, at least. Sam Ali (Yahya Mahayni) is a Syrian man who gets in trouble with the government after getting an entire train car to throw an impromptu party for him as he proposes marriage to his girlfriend Abeer (Dea Liane); apparently anti-government sentiments were heard being shouted from someone in the crowd. He's able to escape through Lebanon to Europe, but his legal status is wobbly enough that he's open for any crazy plan to keep him safe; this crazy plan comes when he sneaks into an invitation-only Godefroy exhibit to stuff himself on the buffet, and the artist proposes buying the rights to Sam's body, to use his back as a canvas. In essence, Sam gets to transform himself from a person with questionable legal right to stay in Europe, to an object with a perfect legal right to do so as he's shuttled from exhibition to exhibition, and ultimately from buyer to buyer. With no other options to speak of, he does so.

The political metaphor at the heart of The Man Who Sold His Skin - white bourgeois Europeans are more comfortable viewing poor Arabs as commodities than people - is obvious. So very obvious that the film doesn't necessarily get around to doing anything with it. In fact, it's generally the case that, in the grand battle between "satire about the way that the art world has turned into a soulless commodities market" and "satire about the way that immigrants are maltreated by self-satisfied middle-class intellectuals", the former wins out pretty much ever time; the movie is biting off a hell of a lot, and while it can sort of chew it all, it's the kind of chewing where you point at your mouth and nod so that the person you're talking to knows that it will be a minute before you can reply.

It's a messy film, one that has a hard time balancing everything it wants to do (there's a romantic plot between Sam and Abeer, made up entirely of frustrated phone calls, that never quite serves as the emotional spine of the movie like Ben Hania obviously wanted it to), and all the snide gags it wants to lob at the art world, but the mess is at least appealing to watch. It's a breezy 104 minutes, buoyed up considerably by Mahayni's excellent performance as a man who goes from panic and desperation to a dismal depression as he starts to realise the full extent of what he's signed up for and how little room it will make for him as a human being, as well as De Bouw's sarcastic work as an egocentric artist whose preening is especially insidious by always looking like hard-boiled realism, and Monica Bellucci, oddly but happily cast as Godefroy's viper of a personal assistant. At the very least, it throws harder at its targets and hits closer to the dead center of them than 2017's The Square, a film with a similar perspective on similar topics. The central image of a man transformed into a living canvas - inspired by a real situation, though the additional of the refugee immigrant angle is Ben Hania's own - is durable enough to carry us through quite a bit of the film on the sheer oddness of it, especially given the film's acerbic way of framing Mahayni's body and face, always as two distinctly separate entities. I can never feel entirely good about a movie that nose-dives right before the finish line as badly as this one does, and that's not the only reason that The Man Who Sold His Skin ends up being less than sum of its parts. But they are pretty good parts.

Which is different than saying that it's not tight, snappy, or smart, or that I generally disliked it. In fact I generally liked it, quite a bit even, and if not for a stunningly bad ending, contrived and tone-deaf, I would surely feel a lot more openly enthusiastic about the thing. Even at it's best, it's the kind of thing that wants to be celebrated for its cunning, timely satire more than it actually wants to go to the trouble of being cunning, and it generally takes easy swings at safe targets. Exactly the sort of movie that ought to get an Oscar nomination, then, and I am happy for The Man Who Sold His Skin that it has had the good fortune to become its truest self, thereby coming to a level of attention that it absolutely would not have received under any other circumstances.

Snark, snark, snark, but in truth, the film has some pretty strong moves, courtesy of director and writer Kaouther Ben Hania. I'm not familiar with her earlier work, which has mostly been in documentaries, and that wouldn't obviously have been the right training ground for the work she's up to here: a slightly arch visual style built around a motif of the camera staying directly behind its subjects' heads, placing them as geometric objects in a brittle world of straight lines and claustrophobically empty rooms. We get one of the boldest examples of this right at the start, in a scene that openly crows about how it's mysteriously disconnected from the rest of the movie: a man we'll later learn is the internationally celebrated artist Jeffrey Godefroy (Koen De Bouw), whose big thing is that he signs his name to everyday objects, thereby rendering them as "art" that sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and he and the people spending the money and the critics praising him for it all openly agree that this is a brilliant indictment of the commercialisation of the art world. In 2011, no less, a mere 90 years or so after that ceased to be a new observation. But to be fair to The Man Who Sold His Skin, if the art world had learned anything in those 90 years, it wouldn't be possible to satirise it on that level. At any rate, when we first meet Godefroy, he's doing none of this, he's just walking through a fearsome space of white floors and white walls with mirrors on seemingly every vertical surface, creating a sense of infinite sterility except when we see his face reflected (we never see it directly). It's the most striking visual moment of the entire movie, which is never exactly what you want from an opening scene, but it anyways gets us off to a good start: in this film, art spaces are geometric boxes of beautifully inhuman hells. Got it.

Shortly thereafter, we meet the man who sold his skin. Or soon will, at least. Sam Ali (Yahya Mahayni) is a Syrian man who gets in trouble with the government after getting an entire train car to throw an impromptu party for him as he proposes marriage to his girlfriend Abeer (Dea Liane); apparently anti-government sentiments were heard being shouted from someone in the crowd. He's able to escape through Lebanon to Europe, but his legal status is wobbly enough that he's open for any crazy plan to keep him safe; this crazy plan comes when he sneaks into an invitation-only Godefroy exhibit to stuff himself on the buffet, and the artist proposes buying the rights to Sam's body, to use his back as a canvas. In essence, Sam gets to transform himself from a person with questionable legal right to stay in Europe, to an object with a perfect legal right to do so as he's shuttled from exhibition to exhibition, and ultimately from buyer to buyer. With no other options to speak of, he does so.

The political metaphor at the heart of The Man Who Sold His Skin - white bourgeois Europeans are more comfortable viewing poor Arabs as commodities than people - is obvious. So very obvious that the film doesn't necessarily get around to doing anything with it. In fact, it's generally the case that, in the grand battle between "satire about the way that the art world has turned into a soulless commodities market" and "satire about the way that immigrants are maltreated by self-satisfied middle-class intellectuals", the former wins out pretty much ever time; the movie is biting off a hell of a lot, and while it can sort of chew it all, it's the kind of chewing where you point at your mouth and nod so that the person you're talking to knows that it will be a minute before you can reply.

It's a messy film, one that has a hard time balancing everything it wants to do (there's a romantic plot between Sam and Abeer, made up entirely of frustrated phone calls, that never quite serves as the emotional spine of the movie like Ben Hania obviously wanted it to), and all the snide gags it wants to lob at the art world, but the mess is at least appealing to watch. It's a breezy 104 minutes, buoyed up considerably by Mahayni's excellent performance as a man who goes from panic and desperation to a dismal depression as he starts to realise the full extent of what he's signed up for and how little room it will make for him as a human being, as well as De Bouw's sarcastic work as an egocentric artist whose preening is especially insidious by always looking like hard-boiled realism, and Monica Bellucci, oddly but happily cast as Godefroy's viper of a personal assistant. At the very least, it throws harder at its targets and hits closer to the dead center of them than 2017's The Square, a film with a similar perspective on similar topics. The central image of a man transformed into a living canvas - inspired by a real situation, though the additional of the refugee immigrant angle is Ben Hania's own - is durable enough to carry us through quite a bit of the film on the sheer oddness of it, especially given the film's acerbic way of framing Mahayni's body and face, always as two distinctly separate entities. I can never feel entirely good about a movie that nose-dives right before the finish line as badly as this one does, and that's not the only reason that The Man Who Sold His Skin ends up being less than sum of its parts. But they are pretty good parts.

Categories: middle east and north african cinema, satire