Write or wrong

In 1909, during the final ten years of his short life, Jack London published a novel called Martin Eden. The story of a young man attempting to make his way in the world by becoming a successful writer, the film was, and was understood to be, London's attempt to showcase all of the maddening problems in his chosen profession, and the unreasonable challenge facing any up-and-coming new writer in simply managing to wedge his foot in the door. But it was also designed to be a scathing assault on the ideas of individualism and meritocracy, shocking ideas for an American author best known then as now for his man-against-the-world adventure stories set in the Alaskan frontier. London was a radical leftist, though, and he considered it a mark of the book's failure that nobody reading it seemed to realise that it was coming from a left-wing perspective.

No such problem is likely to befall the new adaptation of Martin Eden written by Maurizio Braucci & Pietro Marcello, and directed by Marcello. While it is still, first and foremost, the story of a young man attempting, failing, and succeeding to make a name for himself in the literary world, and can be amply appreciated as such, it has a savage sociopolitical edge that I think one would have to be willfully ignoring in order to not see that it's there. It's not, to be clear right at the top, any kind of political harangue. There's some magical alchemy that I find with Italian leftist films, where no matter how openly they talk about their political stance, they always feel more like movies than tracts (I imagine it's related to whatever in the national character made them look at ugly, everyday human suffering and think "the best way to criticise the world that allows this to happen would be through extravagant melodrama", and do this in two separate media*), and Martin Eden is, every inch of it, a wonderfully overripe, sensual, stylistically excessive movie of the sort that "Italian art cinema" has conjured up ever since it was first possible to formulate that phrase.

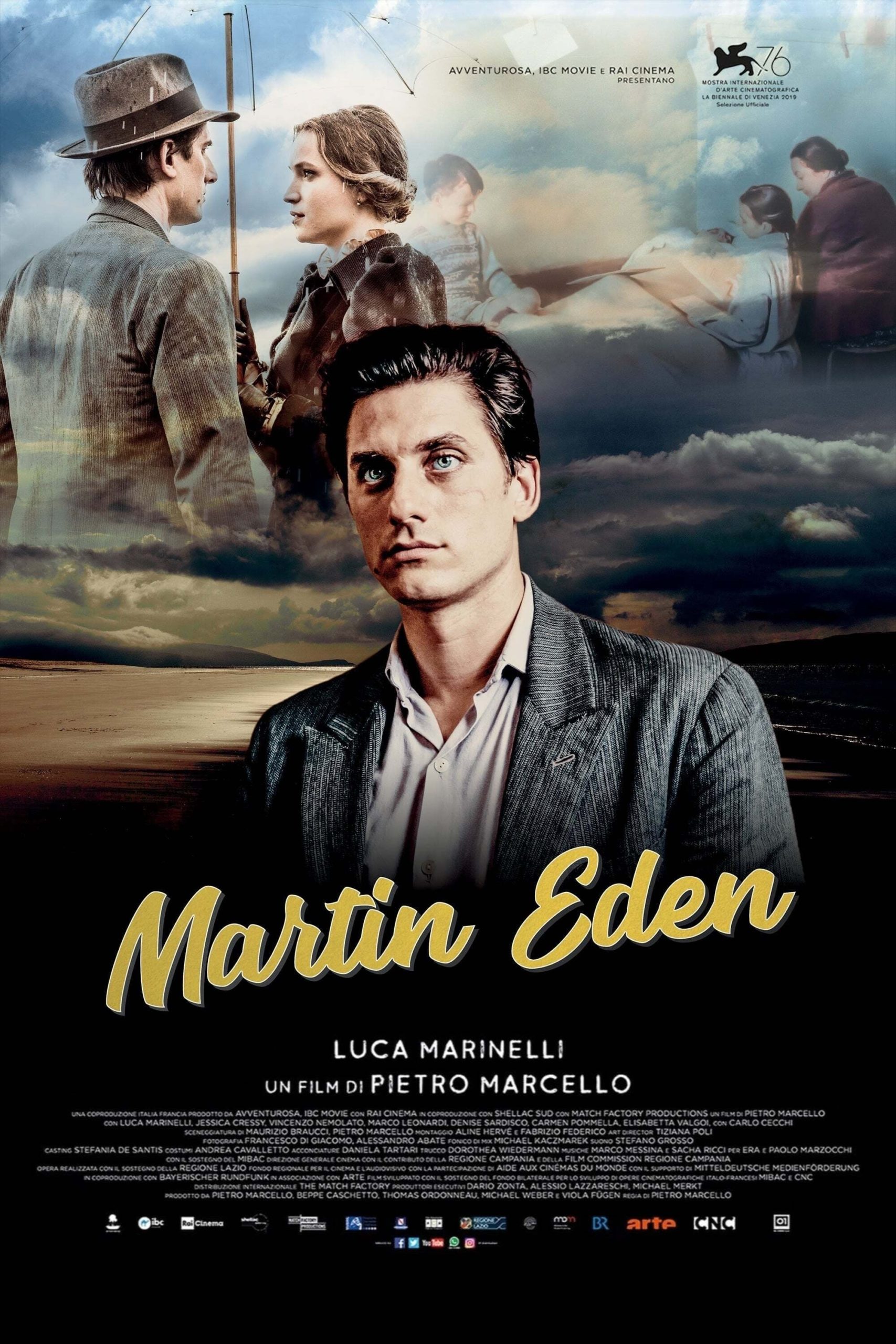

It's a little strange to suggest that the whirlwind of years that make up the story is the "simple" part, but it kind of is the case that the broad sweep of the narrative is the most straightforward part of the entire film: Martin Eden (Luca Marinelli) is a poor sailor living in Naples, sometime in the broadly-described 20th Century. Part of what gives the film its very distinctive timeless quality is a certain fuzziness over just when this is happening: sometimes it feels like the war must have just ended, sometimes it feels a full generation later. Sometimes it even feels like we might be before the war, despite all of the clothes telling us otherwise. Regardless, Martin's low-class world is interrupted by the Orsini family, who befriend him, and thus does he meet the young, marriageable Elena Orsini (Jessica Cressy), with whom he falls instantly in love. Recognising that there's no hope for two people from such vastly different economic worlds ending up together, Martin throws himself into the task of making his fortune, using the only thing he has: his brain, and his talent for writing.

That's an old narrative, of course, and what makes Martin Eden better than just the ten-millionth variation on David Copperfield is in how Marcello builds out the world. The Italy of the film is one fraught with uncertainty and a desperate population, plainly in its period of decline, and this is amply apparent not just in the events of the plot, but in the way the film portrays Naples, with production designers Roberto De Angelis and Luco Servino taking the beautiful age of the city and somehow making it even more weathered. It's a perfect setting for Martin's story, contrasting his rise with the soft dissolution of the world around him; for all that the original novel, set in California, feels like a necessarily American story of hustling and struggling on the brash young frontier, placing the same events in post-WWII Italy feels so much more right, cranking up the tragic elements and forcing an unmistakable irony onto the conflict - Martin fights tooth and nail to join the bourgeoisie even as the bourgeoisie is losing its definition - that considerably sharpens the film's harsh diagnosis of humanity.

In this telling of Martin Eden, it's much harder to feel like Martin's success is something worth celebrating: his dogged individualism, manifested in his furious disgust at a burgeoning socialist movement and his hungry attempts to break away from his blue collar work, forms the backbone of an arc during which Marinelli looks more and more hollow and worn out the longer we go through the film's 129 minutes. The actor is giving a fantastic performance, though very rarely a surprising one: the script defines Martin in a very distinct way, and he mostly just embodies it as written, but with an extraordinarily high level of accomplishment. The film's idea of the character is that he's driven so monomaniacally by his desire for Elena that it stops even looking like love, and instead becomes a Gatsby-esque low-grade insanity. And the more vigorously he fights to define himself as a writer, relishing every small victory and chafing against every major setback, the more harrowed Marinelli's face get, the tighter he holds his body together, the sharper and swifter his emotions grow. Martin Eden charts a narrow course between presenting the title character as a self-destructive monster sacrificing his humanity for a success that's worth almost nothing, and a sympathetic victim of a world that encourages the kind of atomised individualism that Martin is so good at practicing.

If that's all there was, a well-built character study that mercilessly challenges all of the romantic assumptions of the usual story about a young man finding his way in the world, Martin Eden would be good enough. What pushes it in the direction of genuine greatness is how all of this is transformed into lush cinema. I've touched on the rich sense of location, which is helped along by Marcello and the two credited cinematographers, Alessandro Abate and Francesco Di Giacomo. I do not know how exactly their work on the film broke down, but I imagine it has something to do with the glut of different ways the 16mm film stock on which this was all captured has been treated: there are many different styles at play here, some of them only used for one or two shots of boats in a harbor, and at least some of the film we see looks so close to battered old archival footage of midcentury Italy that I'm not honestly sure that it isn't. But that does tell us what the film is up to, roughing up the images, shoving them hard towards different color grading (even if it's just nudging things towards the odd pinks of badly-maintained color stock), giving the whole film the feeling of something that is itself an old object from the post-war years, a lost document rebuilt into something that feels ripped out of history. Even when they're not doing this, the filmmakers are making the most out of the limits of 16mm, indulging in its graininess to make images that have a gritty toughness to them, that pairs well with the tendency towards slightly overexposing the film to wash out everything with diffuse whites. It makes history feel dirty and Naples feel tired. It's both beautiful and raw, and it's the perfect aesthetic for a film about about the unsentimental aspects of a fundamentally sentimental story.

*I am referring to the verismo operas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and of course the neorealist films of the 1940s and '50s)

No such problem is likely to befall the new adaptation of Martin Eden written by Maurizio Braucci & Pietro Marcello, and directed by Marcello. While it is still, first and foremost, the story of a young man attempting, failing, and succeeding to make a name for himself in the literary world, and can be amply appreciated as such, it has a savage sociopolitical edge that I think one would have to be willfully ignoring in order to not see that it's there. It's not, to be clear right at the top, any kind of political harangue. There's some magical alchemy that I find with Italian leftist films, where no matter how openly they talk about their political stance, they always feel more like movies than tracts (I imagine it's related to whatever in the national character made them look at ugly, everyday human suffering and think "the best way to criticise the world that allows this to happen would be through extravagant melodrama", and do this in two separate media*), and Martin Eden is, every inch of it, a wonderfully overripe, sensual, stylistically excessive movie of the sort that "Italian art cinema" has conjured up ever since it was first possible to formulate that phrase.

It's a little strange to suggest that the whirlwind of years that make up the story is the "simple" part, but it kind of is the case that the broad sweep of the narrative is the most straightforward part of the entire film: Martin Eden (Luca Marinelli) is a poor sailor living in Naples, sometime in the broadly-described 20th Century. Part of what gives the film its very distinctive timeless quality is a certain fuzziness over just when this is happening: sometimes it feels like the war must have just ended, sometimes it feels a full generation later. Sometimes it even feels like we might be before the war, despite all of the clothes telling us otherwise. Regardless, Martin's low-class world is interrupted by the Orsini family, who befriend him, and thus does he meet the young, marriageable Elena Orsini (Jessica Cressy), with whom he falls instantly in love. Recognising that there's no hope for two people from such vastly different economic worlds ending up together, Martin throws himself into the task of making his fortune, using the only thing he has: his brain, and his talent for writing.

That's an old narrative, of course, and what makes Martin Eden better than just the ten-millionth variation on David Copperfield is in how Marcello builds out the world. The Italy of the film is one fraught with uncertainty and a desperate population, plainly in its period of decline, and this is amply apparent not just in the events of the plot, but in the way the film portrays Naples, with production designers Roberto De Angelis and Luco Servino taking the beautiful age of the city and somehow making it even more weathered. It's a perfect setting for Martin's story, contrasting his rise with the soft dissolution of the world around him; for all that the original novel, set in California, feels like a necessarily American story of hustling and struggling on the brash young frontier, placing the same events in post-WWII Italy feels so much more right, cranking up the tragic elements and forcing an unmistakable irony onto the conflict - Martin fights tooth and nail to join the bourgeoisie even as the bourgeoisie is losing its definition - that considerably sharpens the film's harsh diagnosis of humanity.

In this telling of Martin Eden, it's much harder to feel like Martin's success is something worth celebrating: his dogged individualism, manifested in his furious disgust at a burgeoning socialist movement and his hungry attempts to break away from his blue collar work, forms the backbone of an arc during which Marinelli looks more and more hollow and worn out the longer we go through the film's 129 minutes. The actor is giving a fantastic performance, though very rarely a surprising one: the script defines Martin in a very distinct way, and he mostly just embodies it as written, but with an extraordinarily high level of accomplishment. The film's idea of the character is that he's driven so monomaniacally by his desire for Elena that it stops even looking like love, and instead becomes a Gatsby-esque low-grade insanity. And the more vigorously he fights to define himself as a writer, relishing every small victory and chafing against every major setback, the more harrowed Marinelli's face get, the tighter he holds his body together, the sharper and swifter his emotions grow. Martin Eden charts a narrow course between presenting the title character as a self-destructive monster sacrificing his humanity for a success that's worth almost nothing, and a sympathetic victim of a world that encourages the kind of atomised individualism that Martin is so good at practicing.

If that's all there was, a well-built character study that mercilessly challenges all of the romantic assumptions of the usual story about a young man finding his way in the world, Martin Eden would be good enough. What pushes it in the direction of genuine greatness is how all of this is transformed into lush cinema. I've touched on the rich sense of location, which is helped along by Marcello and the two credited cinematographers, Alessandro Abate and Francesco Di Giacomo. I do not know how exactly their work on the film broke down, but I imagine it has something to do with the glut of different ways the 16mm film stock on which this was all captured has been treated: there are many different styles at play here, some of them only used for one or two shots of boats in a harbor, and at least some of the film we see looks so close to battered old archival footage of midcentury Italy that I'm not honestly sure that it isn't. But that does tell us what the film is up to, roughing up the images, shoving them hard towards different color grading (even if it's just nudging things towards the odd pinks of badly-maintained color stock), giving the whole film the feeling of something that is itself an old object from the post-war years, a lost document rebuilt into something that feels ripped out of history. Even when they're not doing this, the filmmakers are making the most out of the limits of 16mm, indulging in its graininess to make images that have a gritty toughness to them, that pairs well with the tendency towards slightly overexposing the film to wash out everything with diffuse whites. It makes history feel dirty and Naples feel tired. It's both beautiful and raw, and it's the perfect aesthetic for a film about about the unsentimental aspects of a fundamentally sentimental story.

*I am referring to the verismo operas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and of course the neorealist films of the 1940s and '50s)

Categories: italian cinema, love stories, top 10, worthy adaptations