Joan the maid

Movies about the life of Joan of Arc, the visionary teenager who rallied the French army to victories against the English during the Hundred Years' War and was executed after a politically-motivated show trial for heresy in 1431, are hardly rare. And they are hardly obscure, including this writer's pick for the best movie ever made. So the question that faces Bruno Dumont's twelfth feature, given the imposing English title Joan of Arc (and the somehow even more imposing French title Jeanne), is what does it do that's "new"?

The answer is nothing - indeed, the answer seems to be very brutally and purposefully Nothing. Dumont's previous feature on the same subject, 2017's Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc, does two somethings: first, it focuses, as promised, on the generally un-explored childhood of Joan of Arc, and second, it presents itself as a minimalist heavy metal musical that takes place in a bizarre non-space of sand and scrub and no indication that there is a human world whatsoever. While I clearly don't think the new movie actually does "nothing" with the material, it doesn't have anything slightly like either of those hooks - as a sequel to Jeannette, it picks up the same empty space, and it gestures limply in the direction of being a musical, though this largely comes in the form of internal monologues in the form of songs by the late French experimental pop artist Christophe, who also provides the film's transporting, dream-poppy score. Mostly, it feels like the aesthetic of Jeannette applied to a remake of Robert Bresson's take on the material, 1962's Trial of Joan of Arc, almost certainly the most famous and celebrated version of the story made by an actual French filmmaker, and one to whom Dumont has been compared throughout his career.

What this all means, I would suggest, is that Dumont's Joan of Arc is less about Joan herself than about the nearly 600-year-long persistent obsession with depicting her in art and drama. Or at least what we expect to get out of a Joan story, as both film audiences and filmmakers. Because whatever we expect, this film isn't giving it to us - it even makes a bit of a understated, throughly unfunny joke out of the standard trick of going back to the original transcripts of the trial (like multiple previous films, it draws directly from those transcripts for dialogue) by serving as deliberately bad history. It's almost a travesty of the story - certainly a travesty of the Bresson film (out of all the uncountable screen Joans, that's the only one I'd consider essential homework for this one; more than Dumont's own Jeannette, even), whose ingredients it remixes as a kind of low-boil comedy that doesn't go to the effort of making its jokes funny, when they can simply be peculiar.

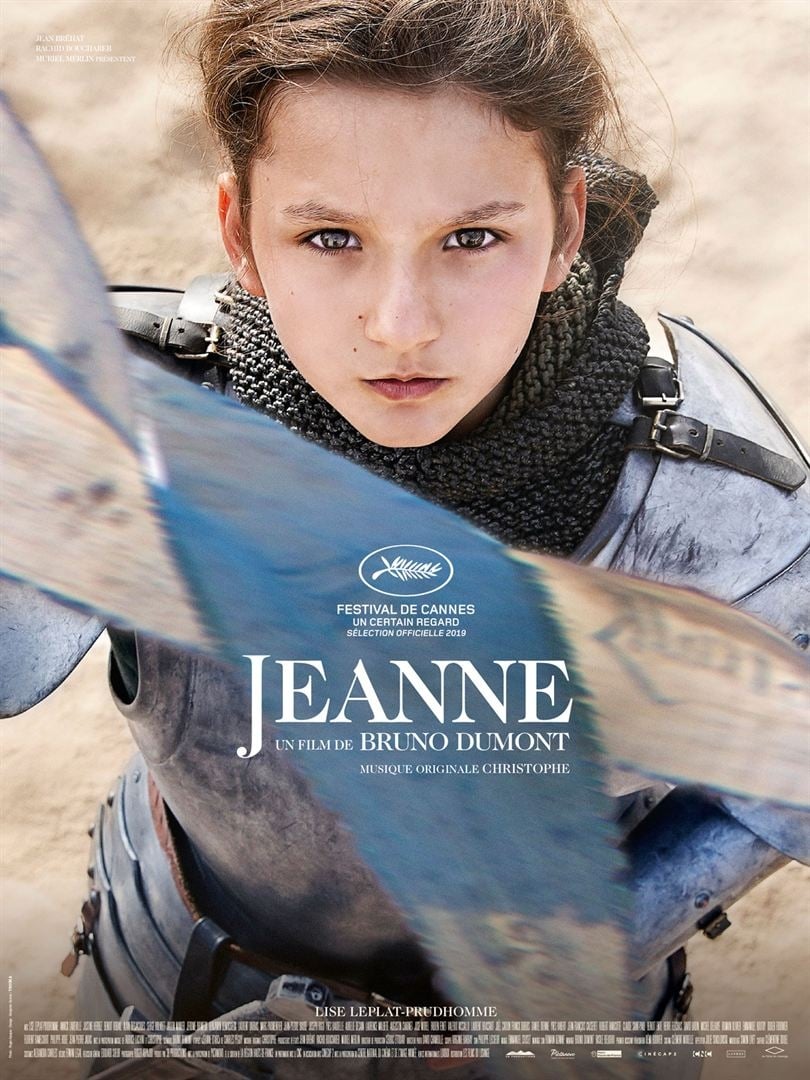

Arguably none of these jokes is more in-your-face than the one the entire film is built around, the casting of Joan herself: she's played by Lise Leplat Prudhomme, one of two actors who played same character in Jeannette. Only it's a bit weirder than that, because in Jeannette, Prudhomme played Joan as an 8-year-old, while Jeanne Voisin played her as a teenager. Bringing back Prudhomme answers, at a stroke, my single biggest complaint with the first movie (not that it's ever "conventional", but it's much more so in its second part), as well as making this an even more startling sequel, by whatever logic guides the creation of sequels to French art movies about Joan of Arc. But mostly, it's startling simply in its own right to see a tween girl decked out in full plate armor that has been scaled down to her tiny frame, boldly declaring the mad, visionary spirituality that made the historical figure such a compelling successful, dangerous figure. It is worth heavily emphasising that Dumont does absolutely nothing to call attention to how fucking weird this is. Nobody, least of all Prudhomme herself, ever makes a gag out of this - arguably, she is the least-funny character in the movie in fact. Dumont, as he has done in other projects, has mostly cast nonprofessionals in the roles of Joan's allies and persecutors, and his casting seems to have been conducted with an eye towards finding the most interestingly squishy-looking human faces that he can guide into responding to all of Joan's declarations with big rubbery-looking exaggerations and cartoon tics. It speaks to nothing but my embarrassing present ignorance of Dumont's earlier career that my first point of comparison to this is his 2014 P'tit Quinquin, the project where he made the (ongoing, so far) shift from lacerating, pessimistic stories about humanity to strange grotesque comedies, doing it in large part by means of the same use of oddly over-expressive faces we see in Joan of Arc's supporting cast.

But the wonky-looking side characters with their big reactions suggestive of a TV sitcom aren't where I was going, as much as they're a crucial part of what gives the film its odd personality. I was talking about Prudhomme, the rock upon which Joan of Arc is founded. Through her, the film gets to have it both ways - three ways, even. The first is the one I was talking about, the sense of detachment from its own content, the uncanniness of seeing a kid proudly declaim the empassioned religious fervor of one of history's most famous martyrs. This bleeds right into the second way, which is that Prudhomme is actually really damn good in the role, as written. She has fire in her guts and the defiant snarl with which she hurls her defense against the hostile judges, much as the stern dignity with which she discusses upcoming battles earlier in the film, entirely bely the actor's age. But her age is still visible every second of the movie, which is the third way: the historical Joan was, after all, extremely, astonishingly young when she achieved all the things she is known for, and there's a sense in which casting a literal child in the role reminds us of that by defamiliarising things; it's shocking for us to see Prudhomme in the role, because everything about Joan is shocking, and that simply doesn't read as clearly when we see an adult like Ingrid Bergman or Milla Jovovich in the role

The whole film is an act of defamiliarisation, really - from the accretion of stories about Joan, from French art cinema, from what we expect out of costume dramas. Building upon Jeannette, the entire long first act takes place on a sandy place on the edge of a plain, where there is no sign of any human settlement; coupled with Christophe's songs (which are mostly used here), the feeling is very much one of abstraction, a pantomime of historical drama in which actors in costumes emerge from the wild to pretend that there is a great war around them, while the film's sole battle scene is represented by a dressage exhibition shot from on high like a Busby Berkeley musical. The even longer second act moves to Amiens Cathedral, France's largest and most well-lit cathedral, which had absolutely nothing to do with Joan's trial. But it makes for a splendid movie location even so, with its extravagant sense of size and the all-encompassing glow that drifts down from its high windows accentuating the white interiors of the space and providing a natural contrast to the humans who feel dwarfed by all of the clean splendor. But even here, nothing feels "real" - Amiens is standing in for "the power structure of the Church", rather than serving as any kind of rational location for the events we see, especially given how many of the scenes involve Prudhomme and her interlocutors simply standing in the middle of a gigantic room. It's every bit as much a pantomime as the first act, or the third act, which returns Joan to her prison cell, played by a little grotto carved into the side of a hill in the middle of nowhere - the essentials of behavior portrayed without any kind of anchor, so the experience is less about watching a story pulled out of history than thinking about the presentation of it: the faces, the poses, the strange ironic humor, the way that Dumont keeps staging Prudhomme to stare directly into the lens of the character for minute after awkward minute, unsettling the entire space in which the movie takes place by making her simultaneously a young actress standing in a field looking at a film crew even while she's convincingly bellowing out military commands.

It's a very peculiar, not to say off-putting film, and I am not in the least surprised that it has been received with extreme coolness - it would be almost disappointing for it to be otherwise. This is entirely the stuff of an intellectual exercise, Dumont breaking down the stuff of a historical drama and then letting us rummage through the pieces, without even the unifying strategy of all those musical numbers that made Jeannette both much weirder and much more watchable as both an experiment and a dry comedy. Yet it's also an intellectual exercise that asks us to recognise and respond to the extreme passion of the main character, and to contextualise this passion in the long history of portraying Joan as one of the most iconic figures in Western history in the second millennium CE. So it's almost that it wants us to have a detached intense emotional experience of our own. It's strange and hard to talk about, and it gets harder in the last, and by far shortest act, which takes all of this and then uses it not merely to comment on our cultural relationship to Joan, but to parody it. So certainly not for everyone, maybe not even for everyone who's already onboard with Dumont's infamously prickly, unpleasant, intellectually detached filmography. But given the absolute wasteland of decent art cinema in the U.S. marketplace in 2020, I will not merely take it, as one of the people it is for, I will do so with great enthusiasm.

The answer is nothing - indeed, the answer seems to be very brutally and purposefully Nothing. Dumont's previous feature on the same subject, 2017's Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc, does two somethings: first, it focuses, as promised, on the generally un-explored childhood of Joan of Arc, and second, it presents itself as a minimalist heavy metal musical that takes place in a bizarre non-space of sand and scrub and no indication that there is a human world whatsoever. While I clearly don't think the new movie actually does "nothing" with the material, it doesn't have anything slightly like either of those hooks - as a sequel to Jeannette, it picks up the same empty space, and it gestures limply in the direction of being a musical, though this largely comes in the form of internal monologues in the form of songs by the late French experimental pop artist Christophe, who also provides the film's transporting, dream-poppy score. Mostly, it feels like the aesthetic of Jeannette applied to a remake of Robert Bresson's take on the material, 1962's Trial of Joan of Arc, almost certainly the most famous and celebrated version of the story made by an actual French filmmaker, and one to whom Dumont has been compared throughout his career.

What this all means, I would suggest, is that Dumont's Joan of Arc is less about Joan herself than about the nearly 600-year-long persistent obsession with depicting her in art and drama. Or at least what we expect to get out of a Joan story, as both film audiences and filmmakers. Because whatever we expect, this film isn't giving it to us - it even makes a bit of a understated, throughly unfunny joke out of the standard trick of going back to the original transcripts of the trial (like multiple previous films, it draws directly from those transcripts for dialogue) by serving as deliberately bad history. It's almost a travesty of the story - certainly a travesty of the Bresson film (out of all the uncountable screen Joans, that's the only one I'd consider essential homework for this one; more than Dumont's own Jeannette, even), whose ingredients it remixes as a kind of low-boil comedy that doesn't go to the effort of making its jokes funny, when they can simply be peculiar.

Arguably none of these jokes is more in-your-face than the one the entire film is built around, the casting of Joan herself: she's played by Lise Leplat Prudhomme, one of two actors who played same character in Jeannette. Only it's a bit weirder than that, because in Jeannette, Prudhomme played Joan as an 8-year-old, while Jeanne Voisin played her as a teenager. Bringing back Prudhomme answers, at a stroke, my single biggest complaint with the first movie (not that it's ever "conventional", but it's much more so in its second part), as well as making this an even more startling sequel, by whatever logic guides the creation of sequels to French art movies about Joan of Arc. But mostly, it's startling simply in its own right to see a tween girl decked out in full plate armor that has been scaled down to her tiny frame, boldly declaring the mad, visionary spirituality that made the historical figure such a compelling successful, dangerous figure. It is worth heavily emphasising that Dumont does absolutely nothing to call attention to how fucking weird this is. Nobody, least of all Prudhomme herself, ever makes a gag out of this - arguably, she is the least-funny character in the movie in fact. Dumont, as he has done in other projects, has mostly cast nonprofessionals in the roles of Joan's allies and persecutors, and his casting seems to have been conducted with an eye towards finding the most interestingly squishy-looking human faces that he can guide into responding to all of Joan's declarations with big rubbery-looking exaggerations and cartoon tics. It speaks to nothing but my embarrassing present ignorance of Dumont's earlier career that my first point of comparison to this is his 2014 P'tit Quinquin, the project where he made the (ongoing, so far) shift from lacerating, pessimistic stories about humanity to strange grotesque comedies, doing it in large part by means of the same use of oddly over-expressive faces we see in Joan of Arc's supporting cast.

But the wonky-looking side characters with their big reactions suggestive of a TV sitcom aren't where I was going, as much as they're a crucial part of what gives the film its odd personality. I was talking about Prudhomme, the rock upon which Joan of Arc is founded. Through her, the film gets to have it both ways - three ways, even. The first is the one I was talking about, the sense of detachment from its own content, the uncanniness of seeing a kid proudly declaim the empassioned religious fervor of one of history's most famous martyrs. This bleeds right into the second way, which is that Prudhomme is actually really damn good in the role, as written. She has fire in her guts and the defiant snarl with which she hurls her defense against the hostile judges, much as the stern dignity with which she discusses upcoming battles earlier in the film, entirely bely the actor's age. But her age is still visible every second of the movie, which is the third way: the historical Joan was, after all, extremely, astonishingly young when she achieved all the things she is known for, and there's a sense in which casting a literal child in the role reminds us of that by defamiliarising things; it's shocking for us to see Prudhomme in the role, because everything about Joan is shocking, and that simply doesn't read as clearly when we see an adult like Ingrid Bergman or Milla Jovovich in the role

The whole film is an act of defamiliarisation, really - from the accretion of stories about Joan, from French art cinema, from what we expect out of costume dramas. Building upon Jeannette, the entire long first act takes place on a sandy place on the edge of a plain, where there is no sign of any human settlement; coupled with Christophe's songs (which are mostly used here), the feeling is very much one of abstraction, a pantomime of historical drama in which actors in costumes emerge from the wild to pretend that there is a great war around them, while the film's sole battle scene is represented by a dressage exhibition shot from on high like a Busby Berkeley musical. The even longer second act moves to Amiens Cathedral, France's largest and most well-lit cathedral, which had absolutely nothing to do with Joan's trial. But it makes for a splendid movie location even so, with its extravagant sense of size and the all-encompassing glow that drifts down from its high windows accentuating the white interiors of the space and providing a natural contrast to the humans who feel dwarfed by all of the clean splendor. But even here, nothing feels "real" - Amiens is standing in for "the power structure of the Church", rather than serving as any kind of rational location for the events we see, especially given how many of the scenes involve Prudhomme and her interlocutors simply standing in the middle of a gigantic room. It's every bit as much a pantomime as the first act, or the third act, which returns Joan to her prison cell, played by a little grotto carved into the side of a hill in the middle of nowhere - the essentials of behavior portrayed without any kind of anchor, so the experience is less about watching a story pulled out of history than thinking about the presentation of it: the faces, the poses, the strange ironic humor, the way that Dumont keeps staging Prudhomme to stare directly into the lens of the character for minute after awkward minute, unsettling the entire space in which the movie takes place by making her simultaneously a young actress standing in a field looking at a film crew even while she's convincingly bellowing out military commands.

It's a very peculiar, not to say off-putting film, and I am not in the least surprised that it has been received with extreme coolness - it would be almost disappointing for it to be otherwise. This is entirely the stuff of an intellectual exercise, Dumont breaking down the stuff of a historical drama and then letting us rummage through the pieces, without even the unifying strategy of all those musical numbers that made Jeannette both much weirder and much more watchable as both an experiment and a dry comedy. Yet it's also an intellectual exercise that asks us to recognise and respond to the extreme passion of the main character, and to contextualise this passion in the long history of portraying Joan as one of the most iconic figures in Western history in the second millennium CE. So it's almost that it wants us to have a detached intense emotional experience of our own. It's strange and hard to talk about, and it gets harder in the last, and by far shortest act, which takes all of this and then uses it not merely to comment on our cultural relationship to Joan, but to parody it. So certainly not for everyone, maybe not even for everyone who's already onboard with Dumont's infamously prickly, unpleasant, intellectually detached filmography. But given the absolute wasteland of decent art cinema in the U.S. marketplace in 2020, I will not merely take it, as one of the people it is for, I will do so with great enthusiasm.