A camp of one's own

The twist is, the glossy magazine test assumes, implicitly, that there's a glossy magazine, or at least its digital equivalent, that can provide us with a more efficient version of the story of the film. In the case of Crip Camp, that might be the case, but if it is I haven't encountered it: the central subject of the film's first half, Camp Jened in upstate New York, was unknown to me even as a rumor or forgotten snippet of history. And it's a good snippet and one well worth bringing back into the light. So while I might very well prefer to have read all about this in a magazine article, Crip Camp will do till the magazine article gets here.

Camp Jened, for those of you laboring in total ignorance like myself, was one of the many summer camps for children of the East Coast middle class, established in 1951 and closed in 1977 (a second incarnation of the camp was open from 1980 to 2009 in a different location). The difference is that Jened was tailored for teenagers with disabilities, treating campers with the assumption that they were capable, autonomous individuals at a period in time when that idea basically hadn't penetrated the mainstream at all. For many of these people, this was the first time they had ever encountered this kind of basic human respect, and it had a radicalising effect: many of the leading lights of the burgeoning disability rights movement of the 1970s and 1980s were former Jened campers, and their time at the camp helped forge the personal relationships that would help that movement go forward.

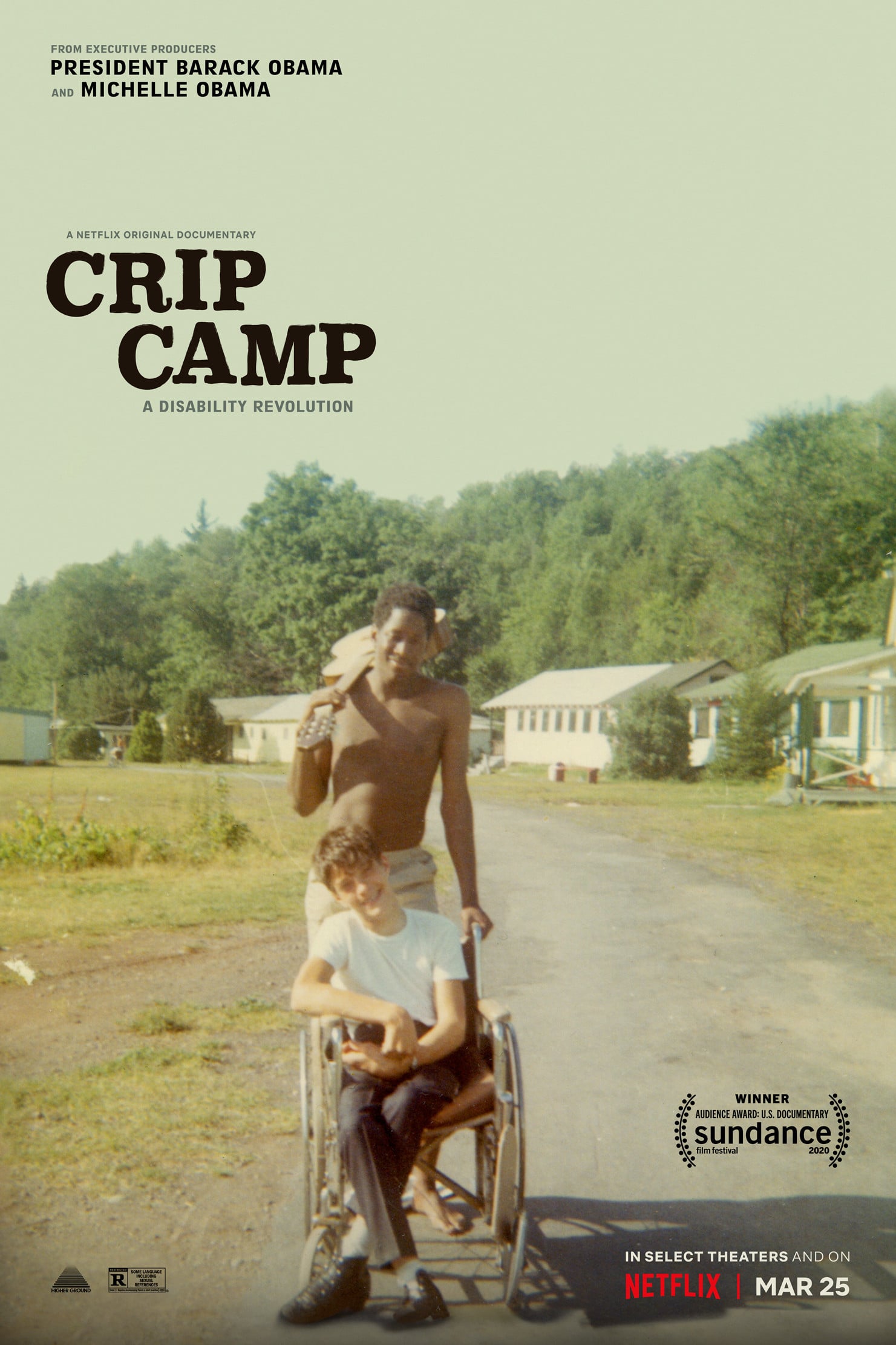

Crip Camp is the story of all of that history, or anyways most of it: it only really starts around 1971, the year that the film's co-director James LeBrecht first attended the camp; it's never made clear, but I gather at least some of the archival footage we see of the camp in those years comes from his own personal collection of home movies. But it does go all the way to 1990, the year that the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed, and then beyond, to the challenges facing the ADA in the early years of its existence, though this part of the story is more in the manner of an extended denouement than the trunk of the story. Much of Crip Camp focuses on Judith Heumann, a Jened veteran who became the de facto leader of the movement, bringing along many Jenedians of all generations with her. But that comes in a bit later (she and LeBrecht were never campers at the same time), when the film has begun its transition to become a history of the activist movement.

And that starts to tell us what doesn't entirely work about the film: it's trying to cover a whole lot. There are, in essence, two complete stories here: first, the film wants to introduce us to Camp Jened as an institution, sketching out its history but mostly interested in the profound emotional impact it had on its campers; second, it wants to follow the early years of the disability rights movement and the intensely hard work people like Heumann poured into scratching out one tiny victory after another over the course of many long, frustrating years. The idea that LeBrecht and co-director Nicole Newnham clearly want us to walk away with is that these are in fact the same story: with Jened, the activists wouldn't have found the personal fortitude to subject themselves to the decades of hard work that led to the ADA and all things afterwards. And it doesn't even seem like this would be a hard story to tell. But Crip Camp also doesn't actually get us there. It seemingly operates under the assumption that simply laying out a chronological ordering of events, it has demonstrated that the first thing necessarily caused the second thing. This simply isn't satisfying storytelling, and it leaves the film feeling more like a chronicle than anything, a feeling only amplified by the film's tendency to keep talking at us.

This vague disconnect between the film's halves also means that it necessarily has to give us a glancing, superficial history, one that can only afford to use its 106 minutes to strew out a bunch of facts before jetting on to the next thing that it needs to cover before it runs out of time. And this is a great pity, because Camp Jened feels more than worth of getting a whole film all to itself, maybe with five minutes of summary at the end covering what Crip Camp explores over the course of its second hour. The footage LeBrecht and Newnham have dug up gives us a wonderful sense of the place, which in 1971 was still hungover from the hippie and free love movements (the film spends a disproportionate amount of time making sure we understand that the campers fucked each other), and as a result gave its participants room to breathe and learn about themselves and live their fullest lives as everyday people. That footage, plus the testimony of the campers filmed in the modern day, reflecting on their experiences and enjoying each other's company, that's the movie, and adding an entire second history on the back end of it just makes things lumpy and arrhythmic. And I know it's a bad habit of film critics to say "why didn't you make this movie instead of the movie you made?", but in this case, right from its title, Crip Camp so plainly wants to be the movie I'm saying they should have made, even thinks it's the movie I'm saying they should have made, that I don't feel bad about it.

That's one big problem. The other is sort of hiding behind that phrase "still hungover from the hippie movement". When it comes down to it, this is still ultimately a film about aging Boomers looking back at what they achieved in their hot, passionate youth, and that's always going to be a smug, self-mythologising genre of nonfiction. Even as we must concede that the first generation of disability rights activists that we see here objectively achieved more than the anti-war activists who tend to show up as the heroes of Boomer mythology, so they have a right to be proud of themselves. Crip Camp still manages to check all the boxes of clichéd ex-hippie self-regard, from its "man, isn't it great that there are no more problems since we solved them all?" vibe (there are at least some nods in the direction of the reality that even in 2020, there are still major gaps in rights for people with disabilities, but they feel more like a cover-your-ass aside than a real attempt to connect the present and past), to its aggravating laundry list of clichéd music cues. The film opens with "For What It's Worth" by Buffalo Springfield playing under the opening credits - it's never pretending to treat this era with anything like a fresh new aesthetic. It's pure stylistic comfort food of the laziest sort, and it instantly imbues the film with a warm, watery feeling of banality that is nothing remotely like the subject deserves.