War is over

The title character in the 2019 Russian art film Beanpole - for yes, "Beanpole" is a character's nickname, and in most contexts that would suggest a lightly quirky dramedy, but I did say "Russian" and so you had best be gearing yourself up for some abject misery - is a veteran of the Second World War, a woman so overwhelmed by what little combat she witnessed before her brain shut down from the trauma of it, that even now, with the war just wrapping up, sometimes she has attacks of PTSD so intense that she simply stops. Without "falling asleep" as such, she loses consciousness, her body goes rigid, and she becomes completely unresponsive to external stimuli. I'm not sure that this a real thing that happens with PTSD or if it's the kind of thing that sounds reasonable enough for a movie; I do know that if she didn't do this, then how would she have an attack while she was playfully wrestling with the small child she has been taking care of while his mother was still in the battlefield? And if she didn't have that attack, how would her body go stiff and lifeless right on top of the child, crushing his longs and smothering him, so that he died of suffocating in a lingering long take as the soundtrack emptied out of every sound other than his increasingly weak whimpers, while we see his tiny hand shuddering as it pokes up next to her head? And of course you might, not unreasonably, say, "well, Jesus fucking Christ, why would you want to have that in a movie?", but I have now, in this review, not only said "Russian art film" but also "abject misery", and wanting is not the point.

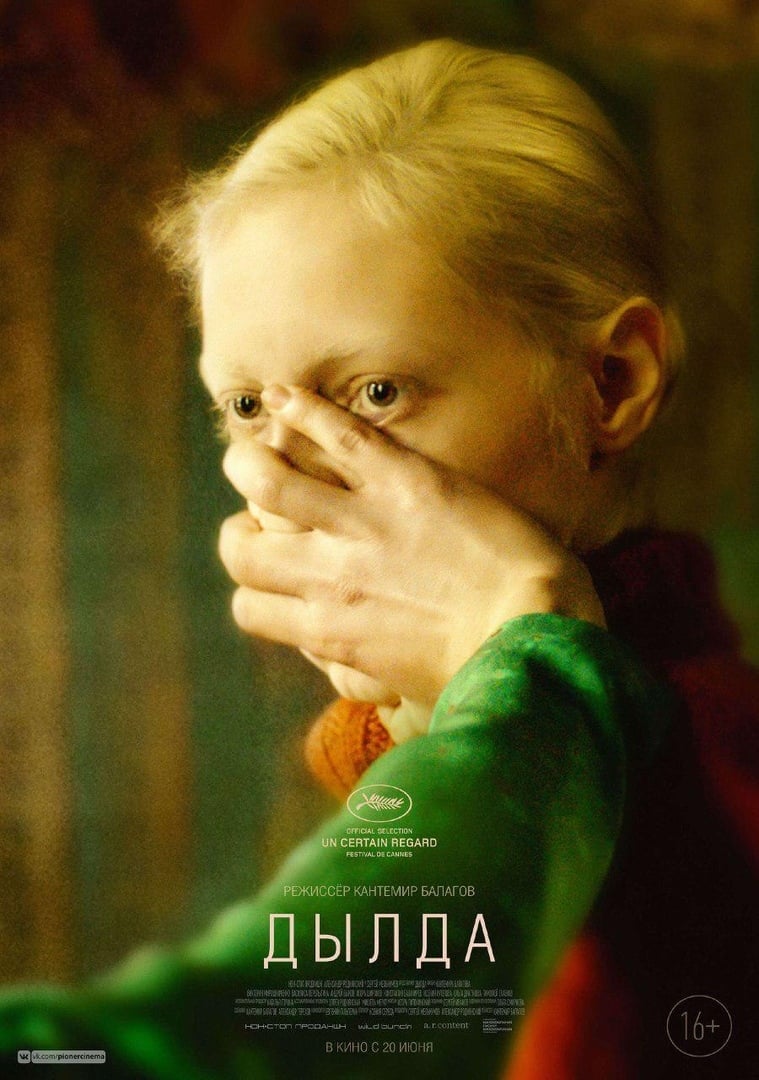

The good news is that after Beanpole has gone to the trouble of murdering a three-year-old, the worst is behind us, and assuming you can recover from that, what's left behind is a pretty potent and convincing depiction of how a society, broken into pieces by the war, looks around, blinking in shock at the reedy light of the post-war order, and tries to take stock of what's left. It does this primarily through Beanpole herself, or to give her proper name to her, Iya Sergueeva (Victoria Miroshnichenko), a nurse in Leningrad, and the woman who seems to be her only friend, Masha (Vasilisa Perelygina), the mother of the dead boy. The 130 minutes we spend in the company of these two women isn't exactly devoid of narrative incident, but telling a story is clearly not a top priority for writers Kantemir Balagov and Aleksandr Terekhov, the former of whom is also the film's director; their scenario is much more about drifting into different corners of Leningrad to see what they find there and how badly life in the Soviet Union was shattered by the war, with special attention to the broken bodies of the patients in the hospital where Iya works (Masha later joins her there), and then retreating to the private spaces where the two women can share the brutal silence of the crumbling world around them.

So, still pretty unpleasant, all things considered, and there's definitely a thick vein of "it's good for you because it's depressing" Art Cinema with a capital A and a capital C running through the film that feels a bit more like a compulsive shtick than real artistic inspiration. Still, it would be doing Beanpole a great disservice to simply write it off as grim Slavic miserabilism. The precision and potency of its psychological observation, and the compelling way it builds its fallen world, are too impressive for that. On the former side of things, we have Iya herself, a remarkable subject for a film played impeccably by first-time film actor Miroshnichenko. The nickname "Beanpole" is in reference to her scrawny frame and exceptional height, and Miroshnichenko has put great thought into how she can work that into Iya's body language, which is really the only way we ever get to learn anything about this conspicuously inarticulate young woman. The actor has devised a way of holding her neck, shoulders, and arms that make it very clear that Iya sees herself as an easy target, perhaps in the most literal possible sense of that term, and so she carries herself in a constant state of cringing, like she's trying to fold herself down and become smaller and invisible somehow. Coupled with her slightly dazed expressions and worn-out, watery eyes, Miroshnichenko gives the impression of a beaten dog, all gangly limbs and sad, morbid expressions. This contrasts nicely with the desperate yearning that seems to radiate out of her body when she interacts with Masha, and her hunger for emotion goes beyond mere romantic or sexual desire (though it includes those things), and into something much more impassioned, even spiritual. It's a pretty devastating piece of acting, pathetically small and expansive at the same time, and while the writers never do anything so crass as to set Beanpole up as the kind of film that positions its characters as "types" in a heavily symbolic narrative, Iya still comes across as somebody who could fill that role in a pinch without losing her definition as an individual.

As for how the film presents all of this, the most striking thing about Beanpole is the sickly yellow cast of Kseniya Sereda's cinematography, with the whole film feeling hot and sticky, damn near bacterial in its toxic hues. The visual portrayal of a rotten world that's gone all wrong is as obvious as it is effective, but there's more, and better stuff to the way the images work than just a bold and viciously ugly color scheme. Balagov and Sereda also employ some very precise depth of focus, sharply dividing most of the film's interiors into distinct planes that separate the characters out from their world and each other. This is most dramatically visible in the hospital sequences, where the helplessness of the sick and war-damaged is intensified by the little pockets that the filmmakers place the characters into. But it's also marked out by its absence, in the moments where Iya and Masha are pressed together by the visuals, given more space to move around each other. And there are other visual tricks the film has up its sleeve: using shaggy handheld cameras sparingly, so that when the film needs to pull them out for effect, it hits harder (especially in one pulverising moment near the end), after the still frames that try to suck up as much of the Leningrad landscape as they can.

Nothing the film does is necessarily surprising; it's all definitely How Art Films Work. And that goes for its gloomy embrace of suffering as a theme, just as much as its aesthetic. But it's getting at something very real about how humans go on in the face of pain and defeat; in its final moments, it even manages to scratch out something that speaks to the durability of the human psyche, its ability to recover from even the worst traumas. It's hardly "uplifiting" in any useful sense, but it does allow some glimmer of optimism to peek out right at the end of a wallow in gloom. Granting that, this is very much the kind of film where, by this point in the review, you surely know if you're the kind of viewer for whom this is likely to be at all appealing or moving, and if you are that viewer, you can probably also predict with a fair degree of accuracy what the experience of watching Beanpole is like; but it's not a bad version of a miserable European art film, just a typical one.

The good news is that after Beanpole has gone to the trouble of murdering a three-year-old, the worst is behind us, and assuming you can recover from that, what's left behind is a pretty potent and convincing depiction of how a society, broken into pieces by the war, looks around, blinking in shock at the reedy light of the post-war order, and tries to take stock of what's left. It does this primarily through Beanpole herself, or to give her proper name to her, Iya Sergueeva (Victoria Miroshnichenko), a nurse in Leningrad, and the woman who seems to be her only friend, Masha (Vasilisa Perelygina), the mother of the dead boy. The 130 minutes we spend in the company of these two women isn't exactly devoid of narrative incident, but telling a story is clearly not a top priority for writers Kantemir Balagov and Aleksandr Terekhov, the former of whom is also the film's director; their scenario is much more about drifting into different corners of Leningrad to see what they find there and how badly life in the Soviet Union was shattered by the war, with special attention to the broken bodies of the patients in the hospital where Iya works (Masha later joins her there), and then retreating to the private spaces where the two women can share the brutal silence of the crumbling world around them.

So, still pretty unpleasant, all things considered, and there's definitely a thick vein of "it's good for you because it's depressing" Art Cinema with a capital A and a capital C running through the film that feels a bit more like a compulsive shtick than real artistic inspiration. Still, it would be doing Beanpole a great disservice to simply write it off as grim Slavic miserabilism. The precision and potency of its psychological observation, and the compelling way it builds its fallen world, are too impressive for that. On the former side of things, we have Iya herself, a remarkable subject for a film played impeccably by first-time film actor Miroshnichenko. The nickname "Beanpole" is in reference to her scrawny frame and exceptional height, and Miroshnichenko has put great thought into how she can work that into Iya's body language, which is really the only way we ever get to learn anything about this conspicuously inarticulate young woman. The actor has devised a way of holding her neck, shoulders, and arms that make it very clear that Iya sees herself as an easy target, perhaps in the most literal possible sense of that term, and so she carries herself in a constant state of cringing, like she's trying to fold herself down and become smaller and invisible somehow. Coupled with her slightly dazed expressions and worn-out, watery eyes, Miroshnichenko gives the impression of a beaten dog, all gangly limbs and sad, morbid expressions. This contrasts nicely with the desperate yearning that seems to radiate out of her body when she interacts with Masha, and her hunger for emotion goes beyond mere romantic or sexual desire (though it includes those things), and into something much more impassioned, even spiritual. It's a pretty devastating piece of acting, pathetically small and expansive at the same time, and while the writers never do anything so crass as to set Beanpole up as the kind of film that positions its characters as "types" in a heavily symbolic narrative, Iya still comes across as somebody who could fill that role in a pinch without losing her definition as an individual.

As for how the film presents all of this, the most striking thing about Beanpole is the sickly yellow cast of Kseniya Sereda's cinematography, with the whole film feeling hot and sticky, damn near bacterial in its toxic hues. The visual portrayal of a rotten world that's gone all wrong is as obvious as it is effective, but there's more, and better stuff to the way the images work than just a bold and viciously ugly color scheme. Balagov and Sereda also employ some very precise depth of focus, sharply dividing most of the film's interiors into distinct planes that separate the characters out from their world and each other. This is most dramatically visible in the hospital sequences, where the helplessness of the sick and war-damaged is intensified by the little pockets that the filmmakers place the characters into. But it's also marked out by its absence, in the moments where Iya and Masha are pressed together by the visuals, given more space to move around each other. And there are other visual tricks the film has up its sleeve: using shaggy handheld cameras sparingly, so that when the film needs to pull them out for effect, it hits harder (especially in one pulverising moment near the end), after the still frames that try to suck up as much of the Leningrad landscape as they can.

Nothing the film does is necessarily surprising; it's all definitely How Art Films Work. And that goes for its gloomy embrace of suffering as a theme, just as much as its aesthetic. But it's getting at something very real about how humans go on in the face of pain and defeat; in its final moments, it even manages to scratch out something that speaks to the durability of the human psyche, its ability to recover from even the worst traumas. It's hardly "uplifiting" in any useful sense, but it does allow some glimmer of optimism to peek out right at the end of a wallow in gloom. Granting that, this is very much the kind of film where, by this point in the review, you surely know if you're the kind of viewer for whom this is likely to be at all appealing or moving, and if you are that viewer, you can probably also predict with a fair degree of accuracy what the experience of watching Beanpole is like; but it's not a bad version of a miserable European art film, just a typical one.