Les Bians

If somebody tells you you're about to watch a French film about retirement-age lesbians, it would be foolhardy to assume you're in for a rollicking good time. Hell, French films about young lesbians are dour enough. When I sat down to screen Two of Us (much more elegantly titled Deux in the original French), I was expecting something like Amour but more gay. While that assessment isn't too far off on paper, Two of Us - for all its harrowing content - is something a film like Amour could never be, and in fact has no interest in being: a delight.

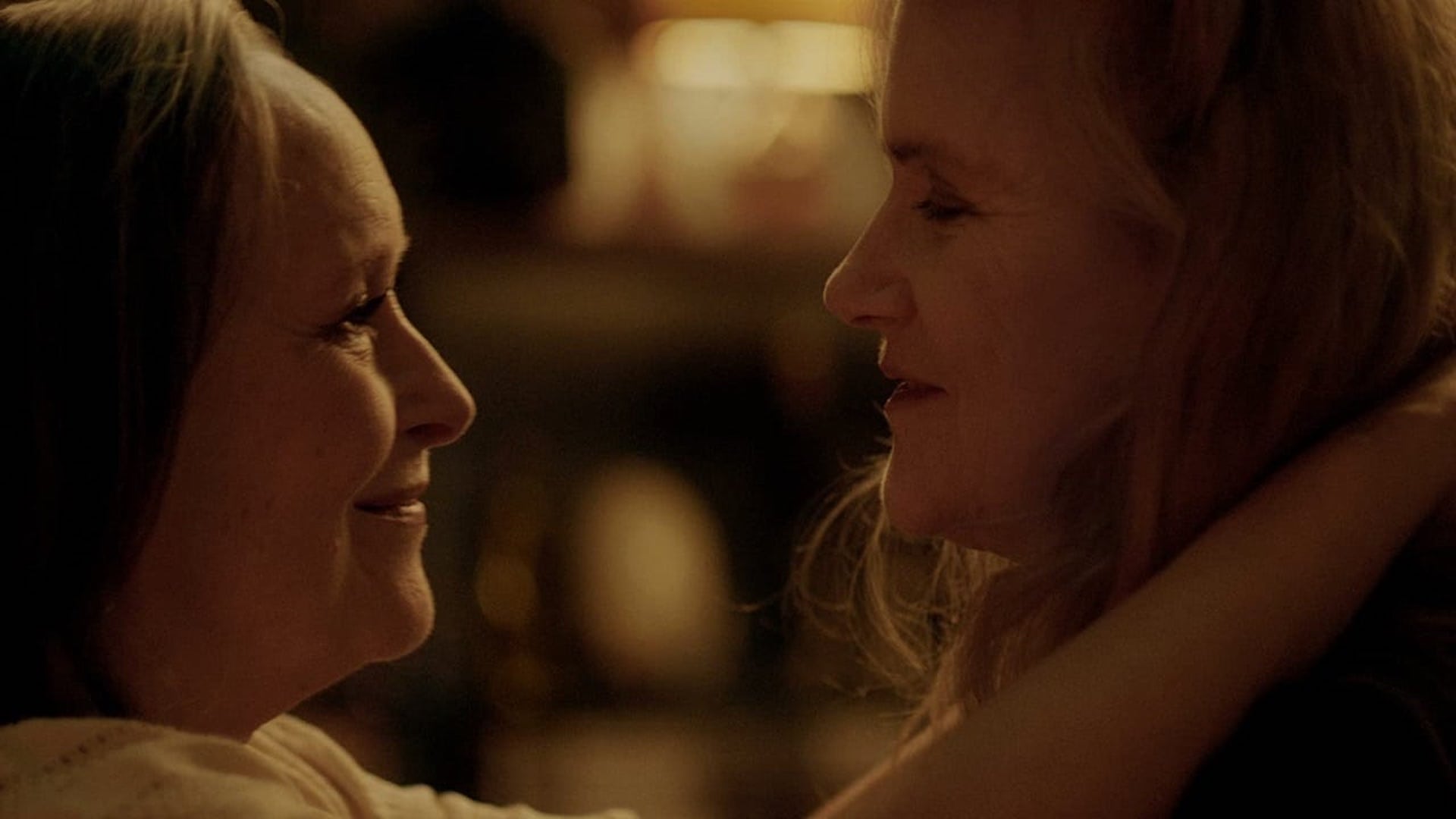

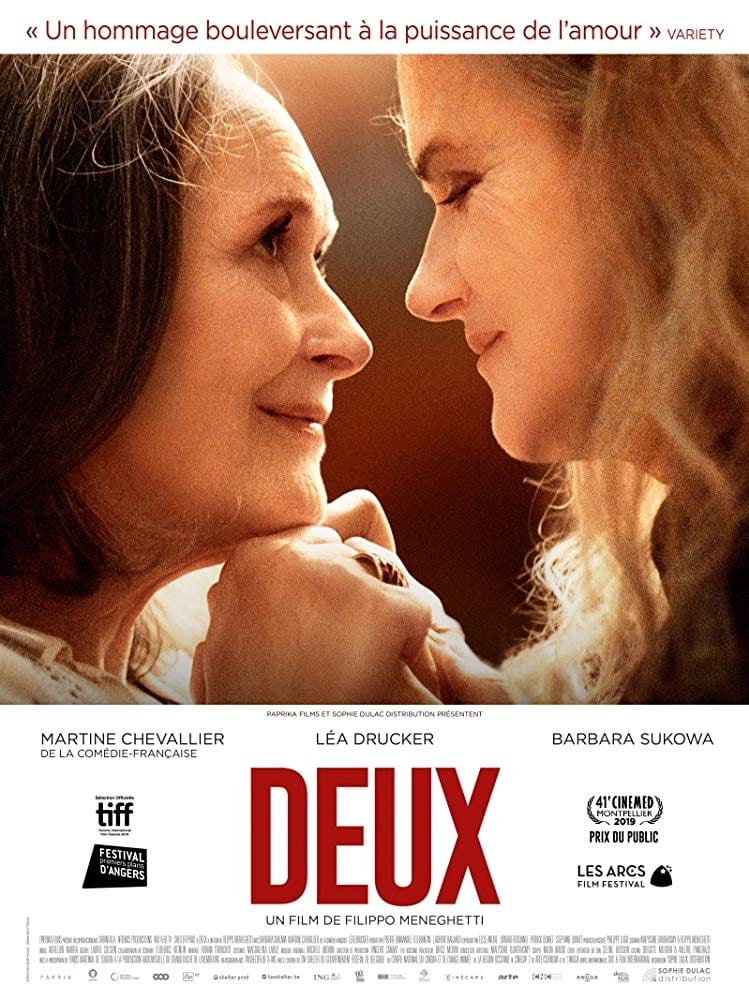

Before I climb out of the rhetorical hole I've just dug myself into, let's glance at the plot we're dealing with here. Pensioners and lovers Madeleine Girard (Martine Chevallier) and Nina Dorn (Barbara Sukowa) occupy both apartments on their floor, with Nina secreting herself away in the mostly unfurnished space across the hall whenever Madeleine has a visit from her family. Madeleine has been unable to tell her children about the woman she has loved passionately for 20 years, just as she finds herself unable to tell them that they are planning to move away together to Rome. Just as tensions over the move reach a boiling point, Madeleine suffers a stroke. While Madeleine convalesces under constant care, unable to speak (it's a metaphor, my darling!), Nina is forced to keep up the charade of merely being an interested neighbor while pining to be by the side of her ailing love.

Now that does sound pretty damn French, while we're talking about it. And it's not like Two of Us is disinterested in scenes of the fabulous Sukowa being generally wrecked and tear-streaked, staring off balconies and whatnot. But it becomes apparent pretty quickly that Two Of Us has a lot on its mind, and elderly ennui is just one facet of that. Nina proves herself to be a force of nature, using every tool at her disposal to take care of Madeleine and get close to her in ways that - in their introspective and subdued manner - echo some rather more bombastic genres and films, including heist pictures, spy thrillers, Parasite, and even Taken for a couple brief and wondrous moments.

By far the boldest thing about Two of Us is that it decides to be gripping in any way. Otherwise, it is delivering a lot of material that is very well-executed, but not exactly treading new ground for European arthouse. Perhaps this is just because we're spoiled, but we couldn't exactly call either of our lead actresses a revelation. Partly because - at least in Sukowa's case, considering her early work with Fassbinder in works like Berlin Alexanderplatz and Lola - they have no need to prove themselves, and partly because they're doing exactly the type of work that this type of movie asks of this type of actress. It's just good luck that they're doing it magnificently, especially Chevallier, who the film relies on heavily. Frequently director Filippo Meneghetti will tell the entire story of a scene by watching the reaction play out on her face, and in one memorable moment only in her eyes. It's spellbinding stuff, but we were already rather expecting to be spellbound, weren't we?

In addition, the cinematography is wonderful, alternating between smooth motion that examines the space in minute detail (an especially affecting proposition considering how well Nina's empty faux apartment underscores the torment of being locked out of one's own life) and austere static shots that let life unfold in front of us in all its many miseries. But there's also no denying the fact that every corner of the film is packed with hoary, easily digestible visual metaphors (gee, what could that conspicuously placed clock possibly mean?). The symbolism of beginning the film with lots of framing using open doors that will eventually be shut is also obvious, though never unsatisfying.

Here's the thing, though. If we didn't have well-executed movies that embrace their tropes, we wouldn't have a lot of my favorite movies, and Two of Us is at the very least already jockeying for an early lead spot in my 2021 top 10. It might not be an earth-rattling exercise in challenging the constraints of film art, but it is an intensely satisfying emotional journey that doesn't skimp on trials and tribulation, but seeks to sweep you up in them rather than crush you under their weight.

Before I climb out of the rhetorical hole I've just dug myself into, let's glance at the plot we're dealing with here. Pensioners and lovers Madeleine Girard (Martine Chevallier) and Nina Dorn (Barbara Sukowa) occupy both apartments on their floor, with Nina secreting herself away in the mostly unfurnished space across the hall whenever Madeleine has a visit from her family. Madeleine has been unable to tell her children about the woman she has loved passionately for 20 years, just as she finds herself unable to tell them that they are planning to move away together to Rome. Just as tensions over the move reach a boiling point, Madeleine suffers a stroke. While Madeleine convalesces under constant care, unable to speak (it's a metaphor, my darling!), Nina is forced to keep up the charade of merely being an interested neighbor while pining to be by the side of her ailing love.

Now that does sound pretty damn French, while we're talking about it. And it's not like Two of Us is disinterested in scenes of the fabulous Sukowa being generally wrecked and tear-streaked, staring off balconies and whatnot. But it becomes apparent pretty quickly that Two Of Us has a lot on its mind, and elderly ennui is just one facet of that. Nina proves herself to be a force of nature, using every tool at her disposal to take care of Madeleine and get close to her in ways that - in their introspective and subdued manner - echo some rather more bombastic genres and films, including heist pictures, spy thrillers, Parasite, and even Taken for a couple brief and wondrous moments.

By far the boldest thing about Two of Us is that it decides to be gripping in any way. Otherwise, it is delivering a lot of material that is very well-executed, but not exactly treading new ground for European arthouse. Perhaps this is just because we're spoiled, but we couldn't exactly call either of our lead actresses a revelation. Partly because - at least in Sukowa's case, considering her early work with Fassbinder in works like Berlin Alexanderplatz and Lola - they have no need to prove themselves, and partly because they're doing exactly the type of work that this type of movie asks of this type of actress. It's just good luck that they're doing it magnificently, especially Chevallier, who the film relies on heavily. Frequently director Filippo Meneghetti will tell the entire story of a scene by watching the reaction play out on her face, and in one memorable moment only in her eyes. It's spellbinding stuff, but we were already rather expecting to be spellbound, weren't we?

In addition, the cinematography is wonderful, alternating between smooth motion that examines the space in minute detail (an especially affecting proposition considering how well Nina's empty faux apartment underscores the torment of being locked out of one's own life) and austere static shots that let life unfold in front of us in all its many miseries. But there's also no denying the fact that every corner of the film is packed with hoary, easily digestible visual metaphors (gee, what could that conspicuously placed clock possibly mean?). The symbolism of beginning the film with lots of framing using open doors that will eventually be shut is also obvious, though never unsatisfying.

Here's the thing, though. If we didn't have well-executed movies that embrace their tropes, we wouldn't have a lot of my favorite movies, and Two of Us is at the very least already jockeying for an early lead spot in my 2021 top 10. It might not be an earth-rattling exercise in challenging the constraints of film art, but it is an intensely satisfying emotional journey that doesn't skimp on trials and tribulation, but seeks to sweep you up in them rather than crush you under their weight.

Brennan Klein is a millennial who knows way more about 80's slasher movies than he has any right to. You can find his other reviews on his blog Popcorn Culture. Follow him on Twitter, if you feel like it.

Categories: french cinema, love stories