Folie à deux

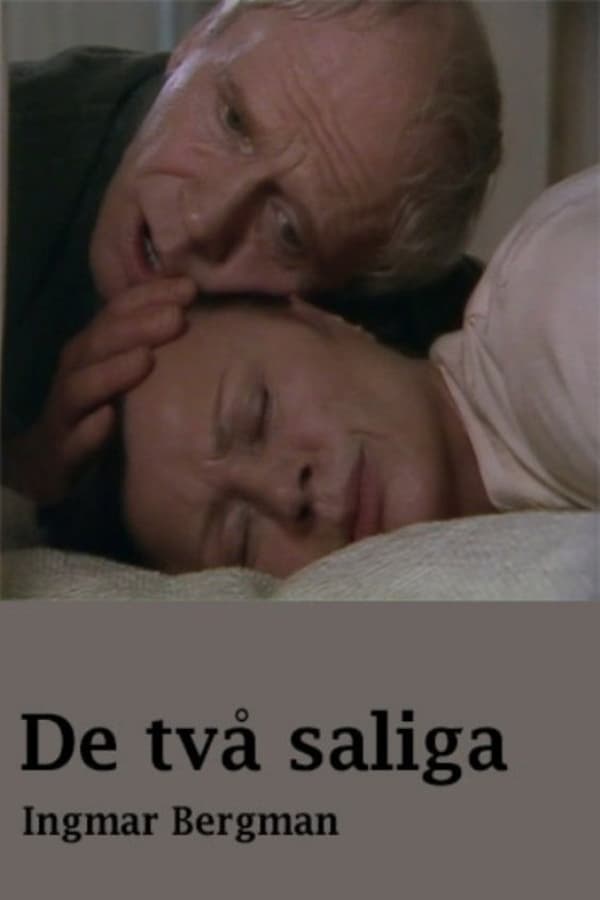

I have had cause to mention multiple times now that the tradition of regarding Fanny and Alexander as Ingmar Bergman's final film is almost entirely a matter of sophistry, but the biggest sophist of all was Ingmar Bergman himself. When his 1984 telefilm After the Rehearsal was released theatrically basically everywhere in the world other than Sweden, it received positive to downright rapturous reviews, but apparently the director himself was actively angry that the sanctity of Fanny and Alexander's status as his farewell to cinema had been thus compromised, and so for his next "don't call it a movie" movie, he stopped dicking around. 1986's The Blessed Ones was shot on videotape rather than 16mm film, making I believe only the third time Bergman had ever worked in that medium, after the 1963 television play A Dream Play and the 1983 recording of The School for Wives, for which the phrase "television play" feels like it would too much of a compliment. And what little documentation of The Blessed Ones I have been able to find in English suggests that this was literally to make sure that it couldn't be blown up to 35mm and shown theatrically.

Apologies for diving right into the technical details of the film right at the head of the review, but to be blunt, The Blessed Ones isn't inherently interesting enough to discourage that kind of pedantry right out of the gate. And anyways, the fact that it was videotaped arguably is the most interesting thing about it; the only competition for that honor would be the fact that this was Bergman's last project with Harriet Andersson, ending his longest-lasting collaboration with any actor. It's a fine showcase for Andersson, at that, though a very strange one, but we'll get there. I was going to bitch about the videography first. The thing is, no matter what allowances we might want to make for it based on the fact that, well heck, this is just what Swedish television did, The Blessed Ones looks pretty rocky. It was not shot by Bergman's longtime cinematography Sven Nykvist, either because that man had a burgeoning career to tend to, or simply because he didn't want to work on video, and this already has a severe negative impact on the subtlety and grace of the lighting (to wit: there isn't any), even setting aside the unimpressive quality of the tape that the filmmakers had to work. The point being, instead of the rich, velvety traps of shadow and stark sunlight that typified the best of Nykvist and Bergman's work together in black and white, or even the boldly raw and caustic graininess of their television collaborations, Per Norén's videography in The Blessed Ones is marked by flat lighting that accentuates the diffuse, foggy softness of videotape without serving any clear artistic purpose. I have, for my entire life as a cinephile, defended Bergman against the not-uncommon charge that his films aren't visually compelling, that he's just using cinema as a recording medium for performances of screenplays, but I admit it; The Blessed Ones is so hard to countenance as anything but cinema-as-recording-medium that it makes me wonder if I've had it wrong this whole time

It doesn't help that the story being thus recorded is certainly no great shakes as a work of psychology or philosophy. Especially its prologue, which has to rank among the worst stretches in Bergman's entire career: two middle-aged people, played by Andersson and Per Myberg, meet in a church and have a gloomy, weighted conversation about the nature of (and likely non-existence of) God. Then, they get on a train together, and we learn a bit more about him, mostly just that he is a tremendous disappointment to his father, ever since the long-ago time that he dropped out of seminary. We know neither of their names at this point, neither of their personalities, not who they are and what they think of each other; it is an entirely cryptic passage that involves nothing but buckets of dialogue being delivered painfully and thoughtfully. I do not, to be entirely clear, blame Andersson and Myberg for any of this. They are doing absolutely everything they can with what they've been given. It's just that they haven't been given anything whatsoever. The opening of The Blessed Ones plays like a parody of Bergman, in which people just start having these monumental chats about the cosmic order of the universe, while the camera stiffly follows them around and captures them in looming close-ups (one of the bigger problems Bergman gets himself into, enabled by a video camera: he and Norén love their chunky zooms).

Thank God it finds its footing, after a jump forward several years, at which point the two people - she's named Viveka, he's named Sune - have been married for some time. I cannot state this too bluntly: there is nothing gained by that prologue. The Blessed Ones will not prove to be one of Bergman's "let us ponder God" movies; it feels more than a little like the twisted sequel of Through a Glass Darkly, with Andersson once again playing a woman in the throes of a mental breakdown, but in this case, that breakdown isn't coming from her terror at attempting to comprehend God's plan for this fallen world. Religious neuroticism is part of it, but mostly, The Blessed Ones is much more tightly focused on the pressures of a domestic partnership and the mental collapse that come when jealousy and guilt and boredom and resentment all get stirred into the mind of a woman who wasn't extremely stable to begin with.

This is all as much as to say: after that sluggish misfire of an opening, this is basically a brisk (just 81 minutes all told) little exercise in watching Harriet Andersson perform a nervous breakdown for our benefit. She does this superbly: it's an unusual role for her, dowdy and morbid and devoid of any sense of self, instead consisting of a chain of animalistic reactions; it feels like a role conceived for Ingrid Thulin, Bergman's go-to-neurotic. But Andersson stretches herself wonderfully to fill this space, contorting her face and body so much that she's frequently unrecognisable. Whether there's any real psychological grounding to what we see, I have my doubts: it's awfully melodramatic in places, and Viveka's mental disorder has symptoms that are much more about what will create the most horrifying possible dramatic tension, rather than anything that I think necessarily exists in the realm of psychotherapy. But let us assume that The Blessed Ones is rather a study of the tensions within marriage, than about character psychology per se; in that light, it works much better, since what happens to Viveka is mostly there to tell us about her relationship with her husband.

And this is not a film with an especially rosy view of that relationship - or any human relationship, for that matter. Marriage, in The Blessed Ones, is hideous and beautiful in equal parts: it's a way for two broken people to feed each other's brokenness, but it's also about how Viveka and Sune support and care for each other, how their relationship is, in its morbid way, the whole center of their respective lives. This manifests mostly in destructive ways: insofar as this has any reputation at all, that reputation is for being one Bergman's darkest, most purely hopeless and nihilistically empty projects, and I find that reputation to be very well-earned. It's not his most wall-to-wall miserable film (it would be very hard to top Cries and Whispers, the film about people who hate each other watching somebody die), but it might be his most inescapable film. It is spiraling downwards towards a crushing, despairing finale, and thanks to the murky video, it doesn't even have the veneer of beautiful images to give us any respite.

If the point of movies is to make us feel something, this passes that test: it is legitimately harrowing. But is it too harrowing? Even in the most depressing Bergman masterpieces, he gives some sense that there's a reason we're being subjected to all the suffering, some attempt to glimpse the powerful, terrible majesty of human experience and the universe. I don't get that from The Blessed Ones. It feels just plain bleak: committed to the idea of human pain without giving us any greater angle from which to appreciate and consider that pain. It's definitely achieving something, and I see no reason to doubt that Bergman knew what he was doing when he made this film; I, however, do not quite know what he was doing, and while I'm glad the film rallies from its dire opening sequence, it never transcends being a far more caustic, bitter redo of the claustrophobic chamber dramas that the director had been cranking out for over twenty years at that point.

Apologies for diving right into the technical details of the film right at the head of the review, but to be blunt, The Blessed Ones isn't inherently interesting enough to discourage that kind of pedantry right out of the gate. And anyways, the fact that it was videotaped arguably is the most interesting thing about it; the only competition for that honor would be the fact that this was Bergman's last project with Harriet Andersson, ending his longest-lasting collaboration with any actor. It's a fine showcase for Andersson, at that, though a very strange one, but we'll get there. I was going to bitch about the videography first. The thing is, no matter what allowances we might want to make for it based on the fact that, well heck, this is just what Swedish television did, The Blessed Ones looks pretty rocky. It was not shot by Bergman's longtime cinematography Sven Nykvist, either because that man had a burgeoning career to tend to, or simply because he didn't want to work on video, and this already has a severe negative impact on the subtlety and grace of the lighting (to wit: there isn't any), even setting aside the unimpressive quality of the tape that the filmmakers had to work. The point being, instead of the rich, velvety traps of shadow and stark sunlight that typified the best of Nykvist and Bergman's work together in black and white, or even the boldly raw and caustic graininess of their television collaborations, Per Norén's videography in The Blessed Ones is marked by flat lighting that accentuates the diffuse, foggy softness of videotape without serving any clear artistic purpose. I have, for my entire life as a cinephile, defended Bergman against the not-uncommon charge that his films aren't visually compelling, that he's just using cinema as a recording medium for performances of screenplays, but I admit it; The Blessed Ones is so hard to countenance as anything but cinema-as-recording-medium that it makes me wonder if I've had it wrong this whole time

It doesn't help that the story being thus recorded is certainly no great shakes as a work of psychology or philosophy. Especially its prologue, which has to rank among the worst stretches in Bergman's entire career: two middle-aged people, played by Andersson and Per Myberg, meet in a church and have a gloomy, weighted conversation about the nature of (and likely non-existence of) God. Then, they get on a train together, and we learn a bit more about him, mostly just that he is a tremendous disappointment to his father, ever since the long-ago time that he dropped out of seminary. We know neither of their names at this point, neither of their personalities, not who they are and what they think of each other; it is an entirely cryptic passage that involves nothing but buckets of dialogue being delivered painfully and thoughtfully. I do not, to be entirely clear, blame Andersson and Myberg for any of this. They are doing absolutely everything they can with what they've been given. It's just that they haven't been given anything whatsoever. The opening of The Blessed Ones plays like a parody of Bergman, in which people just start having these monumental chats about the cosmic order of the universe, while the camera stiffly follows them around and captures them in looming close-ups (one of the bigger problems Bergman gets himself into, enabled by a video camera: he and Norén love their chunky zooms).

Thank God it finds its footing, after a jump forward several years, at which point the two people - she's named Viveka, he's named Sune - have been married for some time. I cannot state this too bluntly: there is nothing gained by that prologue. The Blessed Ones will not prove to be one of Bergman's "let us ponder God" movies; it feels more than a little like the twisted sequel of Through a Glass Darkly, with Andersson once again playing a woman in the throes of a mental breakdown, but in this case, that breakdown isn't coming from her terror at attempting to comprehend God's plan for this fallen world. Religious neuroticism is part of it, but mostly, The Blessed Ones is much more tightly focused on the pressures of a domestic partnership and the mental collapse that come when jealousy and guilt and boredom and resentment all get stirred into the mind of a woman who wasn't extremely stable to begin with.

This is all as much as to say: after that sluggish misfire of an opening, this is basically a brisk (just 81 minutes all told) little exercise in watching Harriet Andersson perform a nervous breakdown for our benefit. She does this superbly: it's an unusual role for her, dowdy and morbid and devoid of any sense of self, instead consisting of a chain of animalistic reactions; it feels like a role conceived for Ingrid Thulin, Bergman's go-to-neurotic. But Andersson stretches herself wonderfully to fill this space, contorting her face and body so much that she's frequently unrecognisable. Whether there's any real psychological grounding to what we see, I have my doubts: it's awfully melodramatic in places, and Viveka's mental disorder has symptoms that are much more about what will create the most horrifying possible dramatic tension, rather than anything that I think necessarily exists in the realm of psychotherapy. But let us assume that The Blessed Ones is rather a study of the tensions within marriage, than about character psychology per se; in that light, it works much better, since what happens to Viveka is mostly there to tell us about her relationship with her husband.

And this is not a film with an especially rosy view of that relationship - or any human relationship, for that matter. Marriage, in The Blessed Ones, is hideous and beautiful in equal parts: it's a way for two broken people to feed each other's brokenness, but it's also about how Viveka and Sune support and care for each other, how their relationship is, in its morbid way, the whole center of their respective lives. This manifests mostly in destructive ways: insofar as this has any reputation at all, that reputation is for being one Bergman's darkest, most purely hopeless and nihilistically empty projects, and I find that reputation to be very well-earned. It's not his most wall-to-wall miserable film (it would be very hard to top Cries and Whispers, the film about people who hate each other watching somebody die), but it might be his most inescapable film. It is spiraling downwards towards a crushing, despairing finale, and thanks to the murky video, it doesn't even have the veneer of beautiful images to give us any respite.

If the point of movies is to make us feel something, this passes that test: it is legitimately harrowing. But is it too harrowing? Even in the most depressing Bergman masterpieces, he gives some sense that there's a reason we're being subjected to all the suffering, some attempt to glimpse the powerful, terrible majesty of human experience and the universe. I don't get that from The Blessed Ones. It feels just plain bleak: committed to the idea of human pain without giving us any greater angle from which to appreciate and consider that pain. It's definitely achieving something, and I see no reason to doubt that Bergman knew what he was doing when he made this film; I, however, do not quite know what he was doing, and while I'm glad the film rallies from its dire opening sequence, it never transcends being a far more caustic, bitter redo of the claustrophobic chamber dramas that the director had been cranking out for over twenty years at that point.