Cut it out

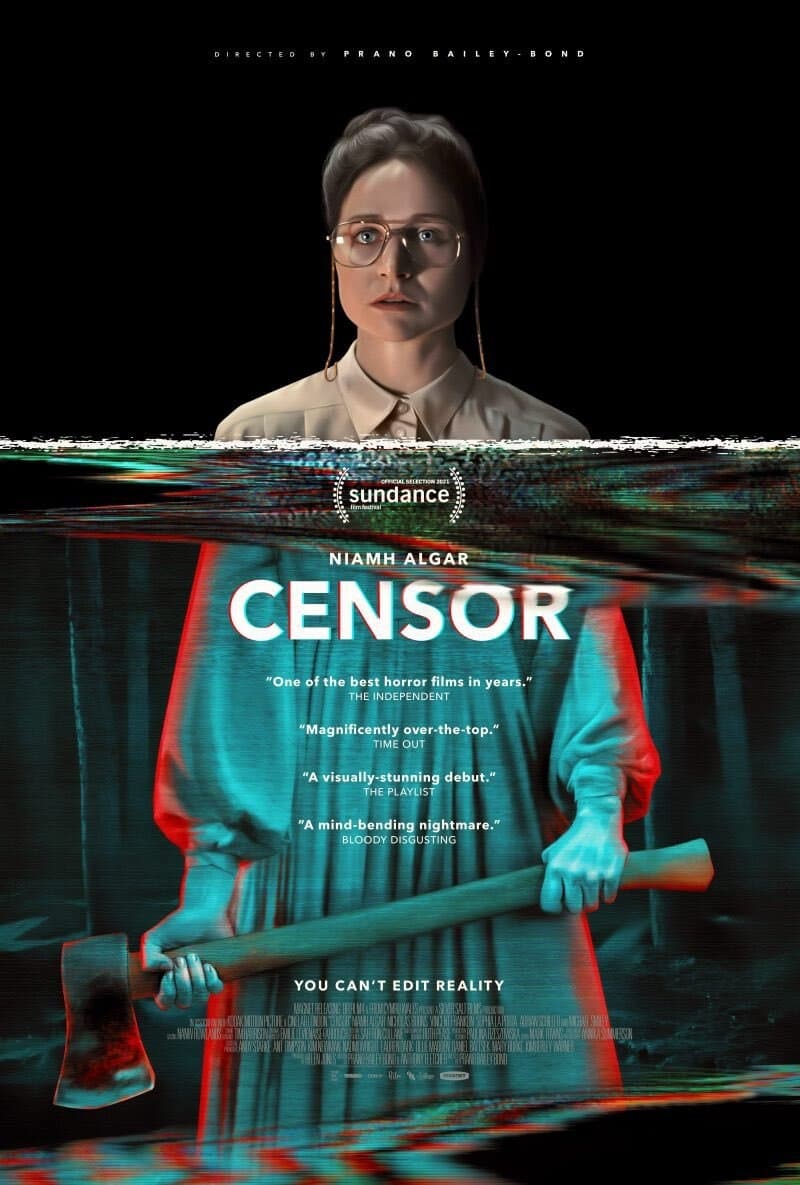

Making homages to the gialli, Italy's cultishly beloved violent, stylish thrillers from the 1970s, has become something of a cottage industry over the last few years, going from a fun celebration of a niche interest to a fairly lazy way to jazz up horror stories with bright colors and cryptic storytelling. It takes more than just dousing a movie in candy colors to stand out, and so that's the first thing to praise about Censor, the extraordinarily self-assured debut feature by Welsh director Prano Bailey-Bond, is that it certainly isn't that. Though it is very candy colored. And very cryptic, for that matter.

Even calling it a giallo homage is skipping ahead a little bit. Even more than that, it's a love letter to the Video Nasties, the notorious collection of movies targeted for prosecution on home video by the British government in the 1980s, built around one of the censors whose job it was to determine how much needed to be cut out of any given movie before it was deemed appropriate for public consumption. This is Enid Baines (Niamh Algar), who as we learn fairly early on lived through a traumatic experience in her childhood, relating to the disappearance of her sister. Whatever happened remains a mystery, and while Enid's parents have finally decided to move on, she insists that her sister is still out there, somewhere.

She's probably not the best candidate, psychologically speaking, to spend all of her days watching violent dismemberment and gougings and all the other revolting things with a tendency to deprave and corrupt, but what actually triggers her psychological break (because obviously there's a psychological break, or we wouldn't have a psycho thriller) is seeing a woman who looks eerily like her sister in the latest film by a particularly notorious director named Frederick North. Soon, she finds herself diving even deeper into the world of violent horror filmmaking than her professional duties already demand, as she tries to figure out what the hell is going on. If anything is going the hell on, given that everyone around her more or less openly assumes that the ugliness of her job has just finally gotten to her.

Whatever is going on, it's perfectly fair, I think, to suggest that Censor gets more batshit as it goes along, and that batshitness is directly connected to Enid's own disintegrating handle on reality. While the film is doing multiple things - celebrating grimy horror, condemning censorship, luxuriating in the vivid stylistic excess of '70s-style horror - the primary focus is on delving into Enid's traumatised soul, and her complete refusal to grapple with, or even name, whatever it was she saw all those years ago. There's not much subtlety around the film's game: a character states outright in dialogue that we can choose to "censor" our memories just like Enid and her colleagues censor movies for objectionable content, and the film enthusiastically draws a straight line between that concept and the entire Video Nasties phenomenon, which it suggests is more about the hang-ups of the censors than actually protecting the world from horribly icky violence. Indeed, there's at least some hint that we're meant to take away from all this that simply appreciating violent filmmaking as filmmaking can be a healthy, productive way to cope with violence in the world.

Mostly, though, we're just here to watch Enid attempt to keep her past safely buried, and see as her grasp on reality starts to collapse while that happens. Censor is absolutely at its best when it's most narrowly focused on being a psychological study, particularly when that psychology is fracturing; it's at its best in the last third, when its form begins to actively mimic Enid's inconsistent grasp on reality, including its use of aspect ratios and the sputtering effects of failing videotape to help situates us in Enid's mental state, while making sure that we understand that whatever we're seeing, it's at least a little bit to the side of whatever is actually going on on in objective reality. The gorgeously oversaturated cinematography by Annika Summerson and the post-production tinkering are at their best here as well, in a film that's overall extremely well-edited and well-shot.

If there's a downside to the films ending being the best part, it's that there is a way in which the rest of the movie has to be "gotten through" a little bit. Not the opening, which is irresistible horror movie cinephilia, jumping into the stuff of the Video Nasties censorship craze with the giddy joy of a filmmaker who is terribly interested in how the sausage gets made and wants us all to ponder the mechanics of censorship as something more nuanced in its negotiations and personal variables than just "the nasty government wants to make it hard to watch upsetting movies".

The middle, though, is a little bit stretched-thin, feining the shape of a mystery more than the material calls for. We're never convinced as much as Enid is that her sister continues to exist, so spending a considerably amount of time following her investigation of where her sister went can't help but feel like it's just the glue getting us from the beginning of the movie to the end, not anything we actually are supposed to about or want to see. And this is also where the film's style is at its most sedate, lacking the fluid cutting between the real world and the pieces of cinema Enid is censoring, and lacking the giallo influence of the final third. The film is best when we feel the artifice all around us, and that drifts away for a bit in the middle. Still, the film's strengths are extraordinary, a marriage of period filmmaking pastiche and psychological disintegration that calls to mind Peter Strickland's breakthrough film, Berberian Sound Studio, from nine years ago. And my God, if Bailey-Bond is cuing herself up to have a Strickland-esque career, just think of the treasures in store in the future!

Even calling it a giallo homage is skipping ahead a little bit. Even more than that, it's a love letter to the Video Nasties, the notorious collection of movies targeted for prosecution on home video by the British government in the 1980s, built around one of the censors whose job it was to determine how much needed to be cut out of any given movie before it was deemed appropriate for public consumption. This is Enid Baines (Niamh Algar), who as we learn fairly early on lived through a traumatic experience in her childhood, relating to the disappearance of her sister. Whatever happened remains a mystery, and while Enid's parents have finally decided to move on, she insists that her sister is still out there, somewhere.

She's probably not the best candidate, psychologically speaking, to spend all of her days watching violent dismemberment and gougings and all the other revolting things with a tendency to deprave and corrupt, but what actually triggers her psychological break (because obviously there's a psychological break, or we wouldn't have a psycho thriller) is seeing a woman who looks eerily like her sister in the latest film by a particularly notorious director named Frederick North. Soon, she finds herself diving even deeper into the world of violent horror filmmaking than her professional duties already demand, as she tries to figure out what the hell is going on. If anything is going the hell on, given that everyone around her more or less openly assumes that the ugliness of her job has just finally gotten to her.

Whatever is going on, it's perfectly fair, I think, to suggest that Censor gets more batshit as it goes along, and that batshitness is directly connected to Enid's own disintegrating handle on reality. While the film is doing multiple things - celebrating grimy horror, condemning censorship, luxuriating in the vivid stylistic excess of '70s-style horror - the primary focus is on delving into Enid's traumatised soul, and her complete refusal to grapple with, or even name, whatever it was she saw all those years ago. There's not much subtlety around the film's game: a character states outright in dialogue that we can choose to "censor" our memories just like Enid and her colleagues censor movies for objectionable content, and the film enthusiastically draws a straight line between that concept and the entire Video Nasties phenomenon, which it suggests is more about the hang-ups of the censors than actually protecting the world from horribly icky violence. Indeed, there's at least some hint that we're meant to take away from all this that simply appreciating violent filmmaking as filmmaking can be a healthy, productive way to cope with violence in the world.

Mostly, though, we're just here to watch Enid attempt to keep her past safely buried, and see as her grasp on reality starts to collapse while that happens. Censor is absolutely at its best when it's most narrowly focused on being a psychological study, particularly when that psychology is fracturing; it's at its best in the last third, when its form begins to actively mimic Enid's inconsistent grasp on reality, including its use of aspect ratios and the sputtering effects of failing videotape to help situates us in Enid's mental state, while making sure that we understand that whatever we're seeing, it's at least a little bit to the side of whatever is actually going on on in objective reality. The gorgeously oversaturated cinematography by Annika Summerson and the post-production tinkering are at their best here as well, in a film that's overall extremely well-edited and well-shot.

If there's a downside to the films ending being the best part, it's that there is a way in which the rest of the movie has to be "gotten through" a little bit. Not the opening, which is irresistible horror movie cinephilia, jumping into the stuff of the Video Nasties censorship craze with the giddy joy of a filmmaker who is terribly interested in how the sausage gets made and wants us all to ponder the mechanics of censorship as something more nuanced in its negotiations and personal variables than just "the nasty government wants to make it hard to watch upsetting movies".

The middle, though, is a little bit stretched-thin, feining the shape of a mystery more than the material calls for. We're never convinced as much as Enid is that her sister continues to exist, so spending a considerably amount of time following her investigation of where her sister went can't help but feel like it's just the glue getting us from the beginning of the movie to the end, not anything we actually are supposed to about or want to see. And this is also where the film's style is at its most sedate, lacking the fluid cutting between the real world and the pieces of cinema Enid is censoring, and lacking the giallo influence of the final third. The film is best when we feel the artifice all around us, and that drifts away for a bit in the middle. Still, the film's strengths are extraordinary, a marriage of period filmmaking pastiche and psychological disintegration that calls to mind Peter Strickland's breakthrough film, Berberian Sound Studio, from nine years ago. And my God, if Bailey-Bond is cuing herself up to have a Strickland-esque career, just think of the treasures in store in the future!