Lost colony

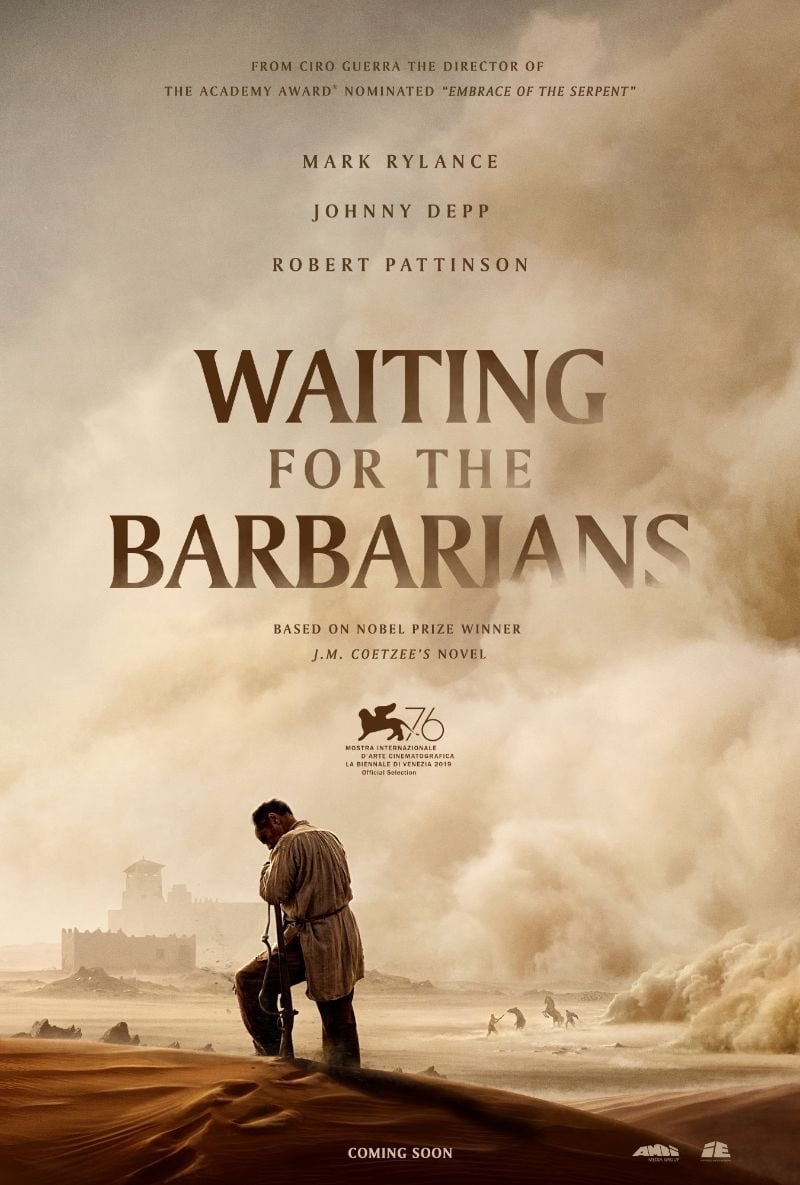

The good news first: Waiting for the Barbarians is one of the finest overall pieces of craftsmanship I have seen in any film released in the United States (for the appropriately cautious definition of "released") in 2020, a heady mixture of gorgeous cinematography, deliberately cautious editing, aggressive sound design, and atmospheric music that combine to do some exquisite, clever storytelling through style. It's always a bit nervewracking when a filmmaker whose work I've enjoyed switches languages - sometimes you get Abbas Kiarostami's Certified Copy and all is well with the world, but sometimes you get Ingmar Bergman's The Touch, and it just sucks - but Ciro Guerra (a Colombian director who hasn't really made enough films to have a reputation yet, but Embrace of the Serpent is masterpiece enough that I don't mind being a little reckless) has moved into English relatively smoothly, at least behind the camera, with a formally complex and very rewarding anticolonial drama.

The bad news next: the story that all that luscious style is in service to is really not all that great. Waiting for the Barbarians is based on a highly-regarded 1980 novel by J.M. Coetzee, who also adapted the film's screenplay, and while I have not read it, I can easily see where this would work on the page. The story is very pointedly anonymous, with a protagonist has no name, working on behalf of the government of an unidentified empire, at an obscure point in time, on a frontier that isn't specified. It's possible to make this amount of fabulistic vagueness work in a movie, undoubtedly, but I'm sure it's easier to make it work in prose, and the thing about the film version of Waiting for the Barbarians is that it doesn't actually work here, anyway. Or even worse, it has specifically been made not to work, after an extremely promising opening quarter.

Anyways, our magistrate is played by Mark Rylance, and he is the head official at an outpost on the farthest edge of the empire, holding steady as his people gear up for their once-a-generation freakout about the "barbarians", the very nondescript way the empire identifies the nomadic culture living in the desert outside the outpost. The magistrate has a good head on his shoulders and is well aware that there is no impending barbarian invasion, but the imperial center has grown nervous enough to send a higher-ranking functionary to check in on him, Colonel Joll (Johnny Depp). Joll, of course, goes on a brief but productive spree of arresting and torturing locals, and while he departs almost as soon as he came, the leery peace has been shatteredm and the magistrate's beatifically ignorant assumption that he can make everything better just by patting Joll's victims on the head and send them on their way will, eventually bear fruit almost as destructive as Joll's inevitable report of the magistrate's pacifist incompetence.

That is, by the way, the opening quarter. The film divides itself very explicitly into four uneven portions, with onscreen text telling us where we are over the course of what will prove to be a very fatal year, and none of the other three are nearly as good as this. It's easy enough to point out why this is: the first chunk is the only one that manages tone correctly. Again, we have a nameless magistrate in a nameless outpost in a nameless region of a nameless empire; there is a certain aesthetic inevitability that the narrative built around all of this will have a diffuse, heavily symbolic quality, one that's openly about the idea of colonialism as an impersonal force of evil. It is very obviously meant to be an indictment of imperialism as a mindset, not the specific actions of a specific empire, and the film, at least initially, does an excellent job of reiterating this. Coetzee was writing from South Africa, which is maybe what he was thinking of; Guerra's crew was based largely in Morocco and somewhat in Italy, and the locations have an unmistakable North African look, while all of the actors playing the featured barbarians are from East Asia, and are wearing unmistakably Mongolian-influenced costumes. So there's definitely no way to pin it down, and the film takes pleasure in creating a dreamy neverland of colonial greed.

This is matched by Chris Menges's breathtaking cinematography, which lets in just a bit too much light and makes everything seem a bit washed-out and sun-faded as a result; the film seems to exist as a series of pastels, with the lines between bodies in dusty khaki, the scrubby ground, and the watery sky all kind of blurring messily. So Carlo Poggioli's costumes are getting in on the fun, too, especially when the more serious, dangerous men from the empire come, in their austere dark cloaks, cutting through the bland earthtones of the rest of the film. Giampiero Ambrosi's score hums along with droning dreaminess, occasionally throwing in a flash of Orientalist cliché for no obvious reason, though it does help to create a dislocated sense in which all of the non-European Old World seems to be existing simultaneously as the distinctly English-as-a-stand-in-for-white-people colonial officers serve as an equally nonspecific contrast.

Rylance and Depp are both excellent in this sequence, giving arch, highly artificial performances; Depp hasn't been this good in a decade or more, squaring his jaw and using his character's strange, off-putting sunglasses as a wonderful prop to hide his eyes and make his clipped, brittle English accent seem to float someplace different than his head, which seems in turn to be floating in a different place than his body. It's a sort of hostile, toad-like performance that feels inhuman in exactly the right ways to make him an embodiment of a generic corrupt imperial order. Rylance has a much harder role: he has to seem like a nice, warm, caring person who is still very much implicated in the diseased colonial system, so he needs to be both appealing and distinctly unpleasant and arrogant. Honestly, no matter how far the film strays, Rylance is still great in it; he has to navigate a hell of a lot, and he never misses a step. But anyway, in this early sequence, he's matching Depp's detached theatricality line-for-line, creating an idea of an imperial bureaucrat but cautiously avoiding playing a character, with a concrete psychology.

Then Depp leaves the film, and it just stops - the only time I have ever felt like a movie needed more of Johnny Depp. But there you have it: once he goes, his prim, artificial performance goes with him, and suddenly the film downshifts: it starts to be specific, grounded, and real, with Rylance never getting a scene partner who can help him reach those levels of artifice again. But the thing is, he's still playing that nameless magistrate in the nameless, with the nameless, and the nameless. Waiting for the Barbarians is still a dreamy, symbolic abstraction - now it's just acting like it all takes place in a real world full of real people. To be clear, this isn't literally because Depp is gone, he's just a handy symptom of the very stark shift in narrative momentum that takes place at this point. And the thing is, abstraction presented in a gauzy, artificial form is stimulating and aesthetically strange. Abstraction presented as a concrete, psychologically realist narrative is just clunky, and ultimately very hollow, and because hollow, very boring. That's basically where the film spends its entire final three-quarters: superficially examining colonialism in a narrative that has no momentum, and moves far too slowly to hit the points that we all knew it was going to hit the minute the word "colonialism" popped up in the plot description. The craftsmanship goes on, and it remains, throughout its running time, one of the most hauntingly lovely films of the year. But its loveliness is papering over a pretty insubstantial drama, one that can't even revive itself when it turns towards torture and suffering near the end. I wanted so very badly to love this film, after that stellar opening act, but it's just got nothing going on under the hood for most of its running time, and the beautiful surface of the hood can only get us so far.

The bad news next: the story that all that luscious style is in service to is really not all that great. Waiting for the Barbarians is based on a highly-regarded 1980 novel by J.M. Coetzee, who also adapted the film's screenplay, and while I have not read it, I can easily see where this would work on the page. The story is very pointedly anonymous, with a protagonist has no name, working on behalf of the government of an unidentified empire, at an obscure point in time, on a frontier that isn't specified. It's possible to make this amount of fabulistic vagueness work in a movie, undoubtedly, but I'm sure it's easier to make it work in prose, and the thing about the film version of Waiting for the Barbarians is that it doesn't actually work here, anyway. Or even worse, it has specifically been made not to work, after an extremely promising opening quarter.

Anyways, our magistrate is played by Mark Rylance, and he is the head official at an outpost on the farthest edge of the empire, holding steady as his people gear up for their once-a-generation freakout about the "barbarians", the very nondescript way the empire identifies the nomadic culture living in the desert outside the outpost. The magistrate has a good head on his shoulders and is well aware that there is no impending barbarian invasion, but the imperial center has grown nervous enough to send a higher-ranking functionary to check in on him, Colonel Joll (Johnny Depp). Joll, of course, goes on a brief but productive spree of arresting and torturing locals, and while he departs almost as soon as he came, the leery peace has been shatteredm and the magistrate's beatifically ignorant assumption that he can make everything better just by patting Joll's victims on the head and send them on their way will, eventually bear fruit almost as destructive as Joll's inevitable report of the magistrate's pacifist incompetence.

That is, by the way, the opening quarter. The film divides itself very explicitly into four uneven portions, with onscreen text telling us where we are over the course of what will prove to be a very fatal year, and none of the other three are nearly as good as this. It's easy enough to point out why this is: the first chunk is the only one that manages tone correctly. Again, we have a nameless magistrate in a nameless outpost in a nameless region of a nameless empire; there is a certain aesthetic inevitability that the narrative built around all of this will have a diffuse, heavily symbolic quality, one that's openly about the idea of colonialism as an impersonal force of evil. It is very obviously meant to be an indictment of imperialism as a mindset, not the specific actions of a specific empire, and the film, at least initially, does an excellent job of reiterating this. Coetzee was writing from South Africa, which is maybe what he was thinking of; Guerra's crew was based largely in Morocco and somewhat in Italy, and the locations have an unmistakable North African look, while all of the actors playing the featured barbarians are from East Asia, and are wearing unmistakably Mongolian-influenced costumes. So there's definitely no way to pin it down, and the film takes pleasure in creating a dreamy neverland of colonial greed.

This is matched by Chris Menges's breathtaking cinematography, which lets in just a bit too much light and makes everything seem a bit washed-out and sun-faded as a result; the film seems to exist as a series of pastels, with the lines between bodies in dusty khaki, the scrubby ground, and the watery sky all kind of blurring messily. So Carlo Poggioli's costumes are getting in on the fun, too, especially when the more serious, dangerous men from the empire come, in their austere dark cloaks, cutting through the bland earthtones of the rest of the film. Giampiero Ambrosi's score hums along with droning dreaminess, occasionally throwing in a flash of Orientalist cliché for no obvious reason, though it does help to create a dislocated sense in which all of the non-European Old World seems to be existing simultaneously as the distinctly English-as-a-stand-in-for-white-people colonial officers serve as an equally nonspecific contrast.

Rylance and Depp are both excellent in this sequence, giving arch, highly artificial performances; Depp hasn't been this good in a decade or more, squaring his jaw and using his character's strange, off-putting sunglasses as a wonderful prop to hide his eyes and make his clipped, brittle English accent seem to float someplace different than his head, which seems in turn to be floating in a different place than his body. It's a sort of hostile, toad-like performance that feels inhuman in exactly the right ways to make him an embodiment of a generic corrupt imperial order. Rylance has a much harder role: he has to seem like a nice, warm, caring person who is still very much implicated in the diseased colonial system, so he needs to be both appealing and distinctly unpleasant and arrogant. Honestly, no matter how far the film strays, Rylance is still great in it; he has to navigate a hell of a lot, and he never misses a step. But anyway, in this early sequence, he's matching Depp's detached theatricality line-for-line, creating an idea of an imperial bureaucrat but cautiously avoiding playing a character, with a concrete psychology.

Then Depp leaves the film, and it just stops - the only time I have ever felt like a movie needed more of Johnny Depp. But there you have it: once he goes, his prim, artificial performance goes with him, and suddenly the film downshifts: it starts to be specific, grounded, and real, with Rylance never getting a scene partner who can help him reach those levels of artifice again. But the thing is, he's still playing that nameless magistrate in the nameless, with the nameless, and the nameless. Waiting for the Barbarians is still a dreamy, symbolic abstraction - now it's just acting like it all takes place in a real world full of real people. To be clear, this isn't literally because Depp is gone, he's just a handy symptom of the very stark shift in narrative momentum that takes place at this point. And the thing is, abstraction presented in a gauzy, artificial form is stimulating and aesthetically strange. Abstraction presented as a concrete, psychologically realist narrative is just clunky, and ultimately very hollow, and because hollow, very boring. That's basically where the film spends its entire final three-quarters: superficially examining colonialism in a narrative that has no momentum, and moves far too slowly to hit the points that we all knew it was going to hit the minute the word "colonialism" popped up in the plot description. The craftsmanship goes on, and it remains, throughout its running time, one of the most hauntingly lovely films of the year. But its loveliness is papering over a pretty insubstantial drama, one that can't even revive itself when it turns towards torture and suffering near the end. I wanted so very badly to love this film, after that stellar opening act, but it's just got nothing going on under the hood for most of its running time, and the beautiful surface of the hood can only get us so far.