Nothing but truffle

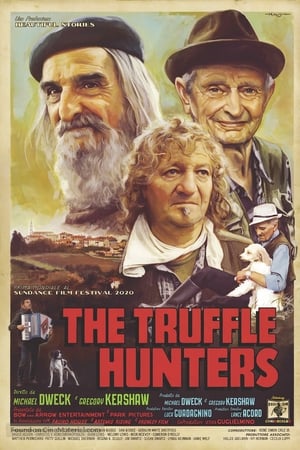

Of all the subgenres that I would never have been able to predict in advance, I think I can safely say that "unusually well-shot documentaries about aging Europeans who use traditional methods to find luxury food items in the wild" is among the unlikeliest. Yet here we are with The Truffle Hunters, only a year on the heels of Honeyland, a Macedonian masterpiece about woman desperately clinging to her mode of life and work well past the point that the world would imagine that she should continue to do so. The Truffle Hunters does not even slightly benefit from the comparison, and the only fair thing to do is to stop making it; but the temptation is strong, I must say, very strong indeed.

The Truffle Hunters takes as its subject a population of elderly men in Piedmont, most of whom are not identified by name in the film, but simply captured in the act of living their lives and doing their work, hunting through the hilly woods to find white Alba truffles, the most highly-regarded and costly of all truffle varieties. This information isn't presented in the film; there is, indeed, no context given for anything outside of the title. The game here is to simply watch raptly as these aging men (who do not seem to have a younger generation ready to take on their vocation after they die, which is something several of them are more or less obsessively concerned with) do what they do, unconcerned with the camera's presence, or a future audience. They're old enough not to have to explain themselves to us, one might say.

The main way these truffle hunters go about their work is with the aid of dogs, and this brings us to one of the film's two great strengths: it is a phenomenal dog movie. It would not be stretching things at all, I don't think, to make the claim that The Truffle Hunters is in its heart a film about the relationship between dogs and their people, and that director-producer-cinematographers Michael Dweck & Gregory Kershaw have merely used the curious world of artisanal truffle hunting as a convenient way to bracket off that topic into a manageable form. For all that it provides an intriguing window into an unexplored world, for all that it drifts into philosophical musings about the loss of tradition (though it does this much less often than I would have anticipated), and for all that it simply gawks in awestruck aesthetic bliss at the mountainous forests of Piedmont, I have a hard time imagining how anybody's strongest response could be to anything else other than the subplot of a man well into his 80s who adores beyond all measure his dog Birba, and spends most of the running time obsessively wondering what will happen to her after he's dead. His hope is that he will be able to find her a home that will be full of love and affection; his fear is that she'll be snatched up by someone who just wants a prize truffle hunter to exploit for her skills. The climax to this line of scenes, which I would not dare to spoil, is probably the most unabashed rah-rah, "hell yes" moment I've seen in a 2020 movie.

For as we learn in The Truffle Hunters, it is a perilous time for the truffle-hunting craft, with much unscrupulous and illicit business behavior ruining the ethereal purity of the work that our subjects view with grave suspicion; dogs are being poisoned or simply disappeared, and most of the old men - the youngest of them in their 70s - have all individually decided to take their hunting knowledge to the grave, for fear of it being abused by greedy exploiters. Birba is one of the ways the film prods its way around this, as are scenes of business negotiations that have a distinctly ugly tang of the men with money failing to understand that there's anything enriching or beautiful about the work.

And beautiful it certainly is, under Dweck & Kershaw's cameras. The other greatest strength of The Truffle Hunters is that it's immaculately composed, a feast of painterly images that only rarely belie the fact that this is a non-fiction film and presumably these shots were all being captured more or less on the fly. The woods have a cathedral-like grandeur; the interiors of the men's houses are perfectly shaped by shafts of overcast light that teases out all of the grain and dirt and texture of the space. These are handsome, classical images, making the film a stately tribute to the innate dignity of the truffle hunters. It's hard to imagine how some of the shots were captured at all, especially the ones indoors, that render the men's homes as cozy, perfectly-framed domestic spaces while still capturing the shapeless naturalism of their daily lives.

Not every visual choice works; the directors do the perhaps inevitable, and attach GoPro cameras to some of the dogs, and we get a couple of fairly long-take shots of dogs bounding through the woods, intently on the hunt. It's cool footage, I suppose, but it goes on for long enough that we get a very good opportunity to think about how little we're actually seeing, and for me at least, how stomach-churning the constant shaking and rattling is as the dogs canter and turn around quickly. It's an intelligent way to add energy to the film, but it's maybe not the energy the film would most benefit from having.

The other, greater problem with The Truffle Hunters is that it's ultimately just not doing very much. The old men are charming, especially the nonogenarian who sneaks out at night because his wife wants him to stay safe in the house at all times, and who gives the film its final statement of thematic intent; the dogs are very good. But it adds up to very little, with the occasional nods in the direction of "the old ways are dying, and that's sad" feeling more like a reluctant gesture towards a message than something the filmmakers really believe in. And the elements that touch on the economics of the truffle market, while compelling and slightly troubling in their own right, sit uncertainly in the film, as if the directors weren't expecting to get that footage and haven't quite decided what to do with it. Basically, we have a purely observational documentary that keeps seeming to imagine that it "ought" to try and formulate an argument or tell a story, both things that Honeyland did so smoothly that you almost wouldn't notice the work going into it. Well, you definitely notice it in The Truffle Hunters; it's a deeply pleasant human study, but it strains to be any more than that. It's a film that's happiest when it's treating its subject in the most superficial way, and while there's joy in that, it certainly limits how actively good the film can be.

The Truffle Hunters takes as its subject a population of elderly men in Piedmont, most of whom are not identified by name in the film, but simply captured in the act of living their lives and doing their work, hunting through the hilly woods to find white Alba truffles, the most highly-regarded and costly of all truffle varieties. This information isn't presented in the film; there is, indeed, no context given for anything outside of the title. The game here is to simply watch raptly as these aging men (who do not seem to have a younger generation ready to take on their vocation after they die, which is something several of them are more or less obsessively concerned with) do what they do, unconcerned with the camera's presence, or a future audience. They're old enough not to have to explain themselves to us, one might say.

The main way these truffle hunters go about their work is with the aid of dogs, and this brings us to one of the film's two great strengths: it is a phenomenal dog movie. It would not be stretching things at all, I don't think, to make the claim that The Truffle Hunters is in its heart a film about the relationship between dogs and their people, and that director-producer-cinematographers Michael Dweck & Gregory Kershaw have merely used the curious world of artisanal truffle hunting as a convenient way to bracket off that topic into a manageable form. For all that it provides an intriguing window into an unexplored world, for all that it drifts into philosophical musings about the loss of tradition (though it does this much less often than I would have anticipated), and for all that it simply gawks in awestruck aesthetic bliss at the mountainous forests of Piedmont, I have a hard time imagining how anybody's strongest response could be to anything else other than the subplot of a man well into his 80s who adores beyond all measure his dog Birba, and spends most of the running time obsessively wondering what will happen to her after he's dead. His hope is that he will be able to find her a home that will be full of love and affection; his fear is that she'll be snatched up by someone who just wants a prize truffle hunter to exploit for her skills. The climax to this line of scenes, which I would not dare to spoil, is probably the most unabashed rah-rah, "hell yes" moment I've seen in a 2020 movie.

For as we learn in The Truffle Hunters, it is a perilous time for the truffle-hunting craft, with much unscrupulous and illicit business behavior ruining the ethereal purity of the work that our subjects view with grave suspicion; dogs are being poisoned or simply disappeared, and most of the old men - the youngest of them in their 70s - have all individually decided to take their hunting knowledge to the grave, for fear of it being abused by greedy exploiters. Birba is one of the ways the film prods its way around this, as are scenes of business negotiations that have a distinctly ugly tang of the men with money failing to understand that there's anything enriching or beautiful about the work.

And beautiful it certainly is, under Dweck & Kershaw's cameras. The other greatest strength of The Truffle Hunters is that it's immaculately composed, a feast of painterly images that only rarely belie the fact that this is a non-fiction film and presumably these shots were all being captured more or less on the fly. The woods have a cathedral-like grandeur; the interiors of the men's houses are perfectly shaped by shafts of overcast light that teases out all of the grain and dirt and texture of the space. These are handsome, classical images, making the film a stately tribute to the innate dignity of the truffle hunters. It's hard to imagine how some of the shots were captured at all, especially the ones indoors, that render the men's homes as cozy, perfectly-framed domestic spaces while still capturing the shapeless naturalism of their daily lives.

Not every visual choice works; the directors do the perhaps inevitable, and attach GoPro cameras to some of the dogs, and we get a couple of fairly long-take shots of dogs bounding through the woods, intently on the hunt. It's cool footage, I suppose, but it goes on for long enough that we get a very good opportunity to think about how little we're actually seeing, and for me at least, how stomach-churning the constant shaking and rattling is as the dogs canter and turn around quickly. It's an intelligent way to add energy to the film, but it's maybe not the energy the film would most benefit from having.

The other, greater problem with The Truffle Hunters is that it's ultimately just not doing very much. The old men are charming, especially the nonogenarian who sneaks out at night because his wife wants him to stay safe in the house at all times, and who gives the film its final statement of thematic intent; the dogs are very good. But it adds up to very little, with the occasional nods in the direction of "the old ways are dying, and that's sad" feeling more like a reluctant gesture towards a message than something the filmmakers really believe in. And the elements that touch on the economics of the truffle market, while compelling and slightly troubling in their own right, sit uncertainly in the film, as if the directors weren't expecting to get that footage and haven't quite decided what to do with it. Basically, we have a purely observational documentary that keeps seeming to imagine that it "ought" to try and formulate an argument or tell a story, both things that Honeyland did so smoothly that you almost wouldn't notice the work going into it. Well, you definitely notice it in The Truffle Hunters; it's a deeply pleasant human study, but it strains to be any more than that. It's a film that's happiest when it's treating its subject in the most superficial way, and while there's joy in that, it certainly limits how actively good the film can be.

Categories: documentaries, gorgeous cinematography