Right to protest

Steve McQueen's Small Axe project has been gestating almost as long as he's had a career as a film director: for a full decade, he was attempting to put together what ended up as a five-part television anthology series of stories (some of them based on true events) about life among the West Indian population in London in the 1970s and '80s. The result is what amounts to a collection of five brand-new McQueen feature films (though four of them are very short features), which as a person who believes not only McQueen hasn't made a bad film, but he has only made excellent films, this concept gets me very excited indeed.

Mangrove, the first episode and by far the longest at 127 minutes, is also a story that has been waiting for a very long time to be told: the incidents and trial that the film depicts took place in 1970 and 1971, and the story was a landmark in British jurisprudence, officially recognising the existence of racial prejudice within the Metropolitan Police. This is the first dramatic telling of that trial and the protests that led up to it, all of fifty years later. And it is, for that matter, an extremely good dramatic telling: courtroom dramas can be some of the most exciting thrillers out there, but they can also be stultifying and talky, and Mangrove manages the excellent feat of being exciting while also being inordinately talky.

But first, it sets the stakes. Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes) opened the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill in 1968, and it immediately attracted attention from the police, who openly hoped that Crichlow (whose previous establishment had been a center of radical political activity) was trying to foment some kind of illegal rebellion, so they could go in and shut him down. The film's version of Frank is much less politically activist than the one in the real world, which gives Mangrove a narrative spine, and gives Parkes a more interesting arc to play; and he plays it tremendously well, at that. His work as a man who just wants to be left alone to run his damn restaurant in peace, but keeps being magnetically attracted by the intellectual charge of the Black intellectuals frequenting the place, proud and terrified in equal measure, is surely in the top echelon of screen performances of 2020, in any medium.

At any rate, the police harassed the Mangrove so often that they ended up creating exactly the protest they didn't want, but wanted to be seen shutting down; in the summer of 1970, the locals took to the streets to protest not just Frank's harassment, but all of the indignities they suffered at the hands of the racist cops in the area. And this protest turned violent, and this violence led to arrests, in which nine defendants (Frank among them) were charged with conspiracy to incite a riot, among other crimes.

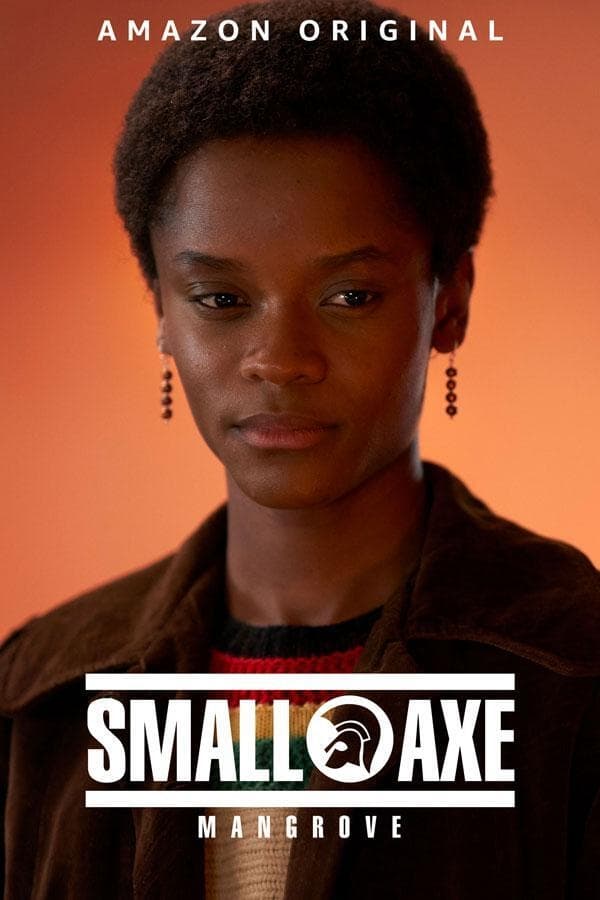

Mangrove is, in effect, two stories: the first is the story of the Mangrove, and the intellectuals and activists who gthered there; the second is the trial. Weirdly, given that there's a direct cause-and-effect relationship between these, I'm not actually sure that they're really communicating in McQueen and Alastair Siddons's script. The editing does a great job of emphasising the gap between the two events, slamming into the early part of the trial across a scene transition almost viciously inelegant and inorganic, and I do think this is a very good choice; it has an artless brutality that perfectly matches the wrathful anger burned into the story. Even so, the two halves feel disjointed in a bad way. The character building done in the first part to establish Frank, as well as British Black Panther leaders Altheia Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright) and Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby), and Darcus's partner Barbara Beese (Rochenda Sandall), who make up the not-quite-half of the Mangrove Nine that Mangrove is prepared to spend time with, gives us a clear sense of who they are, what the stakes of the protest are, and give us plenty of robust speechifying to denounce the cruelty of the police; but once the trial starts, it doesn't really feel like we've been set up to get anything especially productive to apply to the second half.

This is the closest thing that Mangrove has to a real problem, and it's honestly not all that close. Both halves are very well-done in their own ways, though I am even more taken by the courtroom drama, which manages the superhuman feat of making long speeches where the characters literally tell us the themes of the movie feel so perfectly rooted in the passions of the characters that it feels like a natural part of the drama, and not the film stopping cold to lecture at us. This is a message movie, beyond the slightest shadow of a doubt, but it's one that weaves the mesage so naturally into the experience of watching a story about people fighting vigorously against unjust charges that it never has the patronising smugness the words "message movie" tends to imply. These are people who live their lives as cunning rhetoricians; if we learn anything of value in the first part, we learn that. So of course they would use applied rhetoric as an offensive weapon, and of course it would pound us again and again with its lessons.

It's also just a remarkably well-made piece of television. McQueen is an excellent visual storyteller, whose film career started with a bravura exercise in making lots of talking seem enthralling and cinematic, Hunger, and he uses his gifts here mostly in the form of some very focused editing, with Chris Dickens cutting the movie as a series of aggressive reaction shots. We routinely do not watch someone talking, but someone listening, formulating a response, or just being struck with disgust or fear or anger. The courtroom is carved into tight individual spaces, cutting between them so sharply and quickly that the rhythm of the cutting itself starts to add a layer of tension beyond the knotted-up misery on the faces of the very strong cast. This same basic approach is also used in the first part, though there it largely serves to separate Frank, in his close-ups, from the jagged wide shots of the other activists, with their slightly jostled movement and inconsistent framing.

This is not, however, a film that wants us to think about style, but about the stakes of the trial, and the ideological arguments being used to frame those stakes. Style is used to funnel us towards those things and keep the pace up, but the star of the show is the angry declarations played with great ferocity by the actors, and Parkes's strained attempts to keep Frank invisible and interior-focused in the face of those declarations; it is, indeed, the shift in Parkes's acting style that most directly cues us to see the film's shift from political theory as something to talk about in the abstract, to something with dire real-world consequences. It is, in effect, a film about being forced to admit that there's a problem that can't be ignored; the trial of the Mangrove Nine demonstrated this to Britain at large, but Mangrove individualises that by demonstrating it just to Frank. It's a nice telescoping effect that makes the story comprehensible in terms of one human life, giving it considerable more force than if it just wanted to impress upon us the grave historical weight of it all.

Check out Rob's interview with star Malachi Kirby:

Mangrove, the first episode and by far the longest at 127 minutes, is also a story that has been waiting for a very long time to be told: the incidents and trial that the film depicts took place in 1970 and 1971, and the story was a landmark in British jurisprudence, officially recognising the existence of racial prejudice within the Metropolitan Police. This is the first dramatic telling of that trial and the protests that led up to it, all of fifty years later. And it is, for that matter, an extremely good dramatic telling: courtroom dramas can be some of the most exciting thrillers out there, but they can also be stultifying and talky, and Mangrove manages the excellent feat of being exciting while also being inordinately talky.

But first, it sets the stakes. Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes) opened the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill in 1968, and it immediately attracted attention from the police, who openly hoped that Crichlow (whose previous establishment had been a center of radical political activity) was trying to foment some kind of illegal rebellion, so they could go in and shut him down. The film's version of Frank is much less politically activist than the one in the real world, which gives Mangrove a narrative spine, and gives Parkes a more interesting arc to play; and he plays it tremendously well, at that. His work as a man who just wants to be left alone to run his damn restaurant in peace, but keeps being magnetically attracted by the intellectual charge of the Black intellectuals frequenting the place, proud and terrified in equal measure, is surely in the top echelon of screen performances of 2020, in any medium.

At any rate, the police harassed the Mangrove so often that they ended up creating exactly the protest they didn't want, but wanted to be seen shutting down; in the summer of 1970, the locals took to the streets to protest not just Frank's harassment, but all of the indignities they suffered at the hands of the racist cops in the area. And this protest turned violent, and this violence led to arrests, in which nine defendants (Frank among them) were charged with conspiracy to incite a riot, among other crimes.

Mangrove is, in effect, two stories: the first is the story of the Mangrove, and the intellectuals and activists who gthered there; the second is the trial. Weirdly, given that there's a direct cause-and-effect relationship between these, I'm not actually sure that they're really communicating in McQueen and Alastair Siddons's script. The editing does a great job of emphasising the gap between the two events, slamming into the early part of the trial across a scene transition almost viciously inelegant and inorganic, and I do think this is a very good choice; it has an artless brutality that perfectly matches the wrathful anger burned into the story. Even so, the two halves feel disjointed in a bad way. The character building done in the first part to establish Frank, as well as British Black Panther leaders Altheia Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright) and Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby), and Darcus's partner Barbara Beese (Rochenda Sandall), who make up the not-quite-half of the Mangrove Nine that Mangrove is prepared to spend time with, gives us a clear sense of who they are, what the stakes of the protest are, and give us plenty of robust speechifying to denounce the cruelty of the police; but once the trial starts, it doesn't really feel like we've been set up to get anything especially productive to apply to the second half.

This is the closest thing that Mangrove has to a real problem, and it's honestly not all that close. Both halves are very well-done in their own ways, though I am even more taken by the courtroom drama, which manages the superhuman feat of making long speeches where the characters literally tell us the themes of the movie feel so perfectly rooted in the passions of the characters that it feels like a natural part of the drama, and not the film stopping cold to lecture at us. This is a message movie, beyond the slightest shadow of a doubt, but it's one that weaves the mesage so naturally into the experience of watching a story about people fighting vigorously against unjust charges that it never has the patronising smugness the words "message movie" tends to imply. These are people who live their lives as cunning rhetoricians; if we learn anything of value in the first part, we learn that. So of course they would use applied rhetoric as an offensive weapon, and of course it would pound us again and again with its lessons.

It's also just a remarkably well-made piece of television. McQueen is an excellent visual storyteller, whose film career started with a bravura exercise in making lots of talking seem enthralling and cinematic, Hunger, and he uses his gifts here mostly in the form of some very focused editing, with Chris Dickens cutting the movie as a series of aggressive reaction shots. We routinely do not watch someone talking, but someone listening, formulating a response, or just being struck with disgust or fear or anger. The courtroom is carved into tight individual spaces, cutting between them so sharply and quickly that the rhythm of the cutting itself starts to add a layer of tension beyond the knotted-up misery on the faces of the very strong cast. This same basic approach is also used in the first part, though there it largely serves to separate Frank, in his close-ups, from the jagged wide shots of the other activists, with their slightly jostled movement and inconsistent framing.

This is not, however, a film that wants us to think about style, but about the stakes of the trial, and the ideological arguments being used to frame those stakes. Style is used to funnel us towards those things and keep the pace up, but the star of the show is the angry declarations played with great ferocity by the actors, and Parkes's strained attempts to keep Frank invisible and interior-focused in the face of those declarations; it is, indeed, the shift in Parkes's acting style that most directly cues us to see the film's shift from political theory as something to talk about in the abstract, to something with dire real-world consequences. It is, in effect, a film about being forced to admit that there's a problem that can't be ignored; the trial of the Mangrove Nine demonstrated this to Britain at large, but Mangrove individualises that by demonstrating it just to Frank. It's a nice telescoping effect that makes the story comprehensible in terms of one human life, giving it considerable more force than if it just wanted to impress upon us the grave historical weight of it all.

Check out Rob's interview with star Malachi Kirby: