Kane and suffering

My first response to Mank has absolutely nothing do with the what we do see in the film, and everything to do with what we don't: this is not, as was rumored, "Raising Kane: The Movie", and for that I am grateful. "Raising Kane", if you have the good fortunate not to have read it, is film critic Pauline Kael's 1971 introduction to the published script of Citizen Kane in which she spent 50,000 tendentious, ill-researched words defaming Orson Welles and claiming that Herman J. Mankiewicz wrote the entirety of that screenplay and was as such the most important creative contributor to the film. The essay had been fully debunked within a few years of its publication, but it dealt a blow to Welles's reputation, as part of the overall critical turn against that director that was conventional wisdom until sometime in the 1990s.

The Mank screenplay dates to the tail end of that period, when Jack Fincher, father of up-and-coming director David Fincher, wrote a biopic of Mankiewicz that was in large part derived from "Raising Kane". David, in finally completing his decades-long dream of bringing his father's script to life, has backed down on that aspect of the project a bit - not enough! There is still a final act (of, like, five or six - it is one hell of a cluttered film, with a great deal more plot than is good for it) that has substantial scenes of Welles (played here by Tom Burke as an impatient dilettante with no personal charisma; his is the worst performance in a generally well-acted ensemble) acting entitled and pissy in a way that certainly doesn't suggest any real affection for him, or Citizen Kane, or movie directors, or cinema. Still, there's no sense in which the "point" of Mank is to slam Welles and give all the credit for Kane to Mankiewicz - there's not really any point in the film where it becomes "the making of Citizen Kane" at all, or where we're meant to find this interesting because the protagonist was involved in the creation of the officially-anointed Best Movie Ever Made. Welles barely even registers as a character until near the end of the 132-minute film. It is much more a film about the thousand petty indignities of being a working screenwriter in Hollywood, and of the difficulty of preserving one's sense of moral optimism in any industry that depends as much as Hollywood does on the most unbridled form of capitalism.

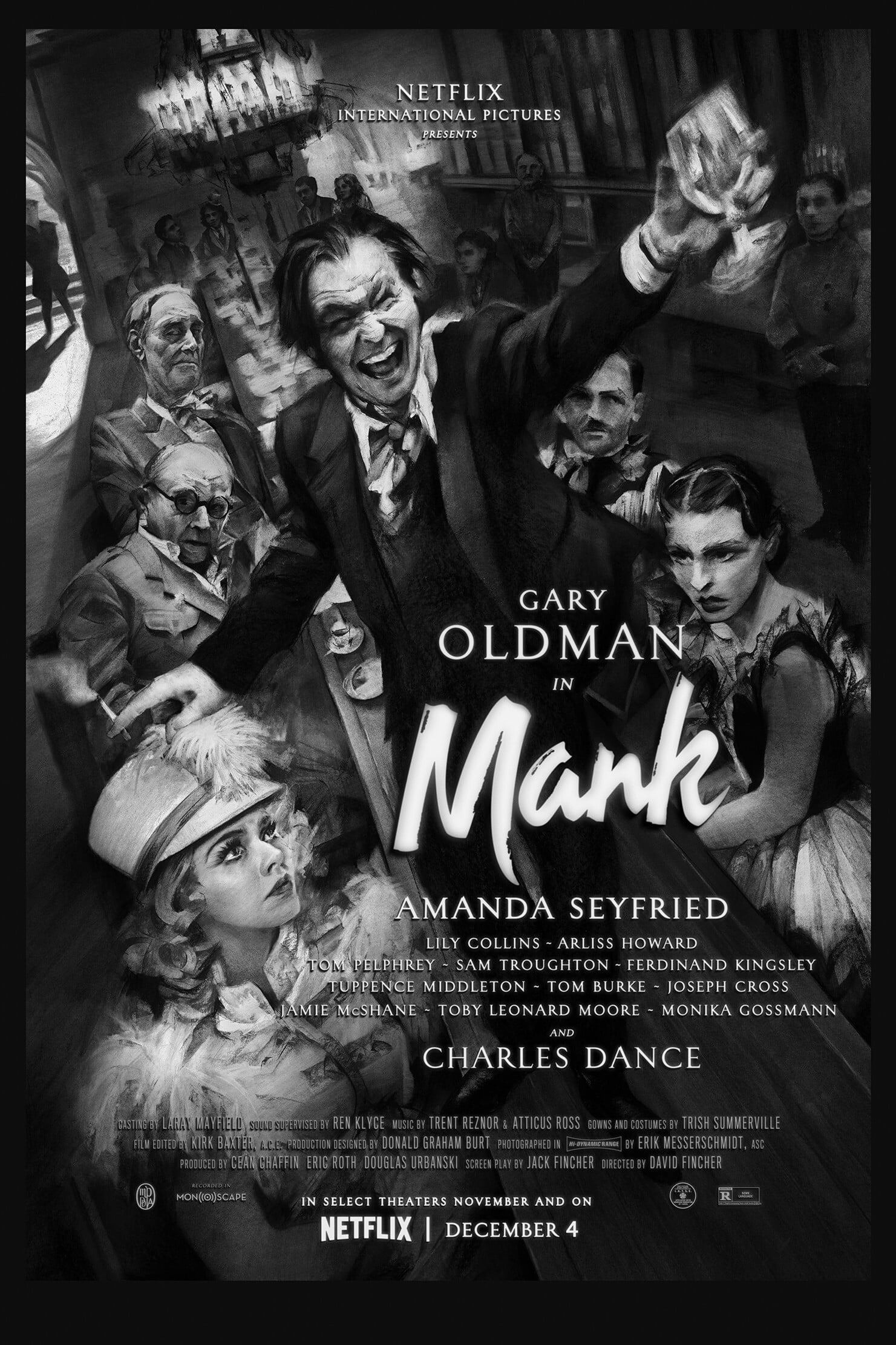

My second response to Mank is to be blown away by how lush the production is. To begin with, the score by Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross is one of the year's very best, a nostalgic dive into period-appropriate motifs with a sharp modernist edge that keeps it from being just pastiche (though if it were just a pastiche, it would be the film's best). It's also a remarkably handsome film, between Donald Graham Burt's production design and Trish Summerville's costumes, which lovingly re-create Los Angeles in the late 1930s with more of an eye towards the glossy trappings of movies of the period than to placing us into living history. And Erik Messerschmidt's black-and-white cinematography is some of the most stupidly beautiful stuff of any movie from 2020, finding a way to make charcoal grey glow with a digital sheen, and reminding us that Fincher is one of the few directors who has historically given actual thought to how to embrace the characteristics of digital cameras rather than force them to pretend to be film cameras. The irony is that Mank's images are actually trying to mimic film in some ways, leading to a film that has been littered with digital "film scratches" and "cigarette burns, despite not actually looking even a little bit like it was shot in the '30s or '40s - not in the way that blacks and whites register, not in the way that it's blocked, not in the shot scales being favored.

And this gets to the awkward problem that, while Mank is incredibly beautiful, it's perhaps not beautiful in a productive way. The visuals tend to get in the way of the movie, especially all of those lush charcoal greys that took Fincher and Messerschmidt so much obvious work to set up, making it more than a little visually claustrophobic. It is, indeed, quite a gloomy film, not in the way of film noir (or the proto-noir found in Citizen Kane), but simply in a a mordant, heavy way, one in which every human interaction is freighted with solemnity. This is sort of the only way Fincher has made movies (ten years later, I still routinely think about Nick Davis's description of the cinematography in The Social Network: "like a state funeral for the family cat"), with an obsessive meticulousness and technical perfection that end up feeling a bit exhausting and airless, and this sometimes fits the material better than others. It fits Mank particularly badly, given its pervasive engagement with 1930s filmmaking norms; it ends up being something of a hybrid between the artificial snappiness of classical Hollywood and the glowering seriousness of a modern prestige film, an awfully clunky marriage indeed. It's most obvious in the dialogue: Mankiewicz was a major writer of bantering, prattling speech in the '30s, with a slightly bitter sense of wit that leads to lots of cutting one-liners and lively monologues in his work. Jack Fincher has made the reasonable choice to mimic that style of dialogue in Mank, leading to a very talky movie, but without the keen understanding of rhythm that made '30s movies clip by so well. This ends up sounding muddy and cluttered and slow, and the deliberately fuzzy soundtrack, mimicking '30s sound recording and mixing, doesn't help matters out.

This is all a lot of words without ever getting into the heart of Mank, but that's in part because I'm not sure what the heart of the movie even is. Obviously, it's Mankiewicz himself, played by Gary Oldman with a breezy raconteur's warmth, though he leans a bit too far into mushmouthed clichés when playing the writer's alcoholism; but I don't know if I confidentally say what about Mankiewicz. The script covers a lot of ideas in a lot of ways, but largely hinges on the back-and-forth contrast between two eras. One is 1939, when Mank, recovering from a car accident (that he didn't cause), tried to crank out a first draft of the Kane script with the help of a British amanuensis named Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), drawing from his years of history as a frequent guest of William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and Marion Hearst (Amanda Seyfried) at the former's monstrous white elephant of an estate in San Simeon to tell the story of a Hearst-like newspaper magnate with a heart of poison. The other is 1934, when Mank watched with disgust as Hollywood elites, including the slimy Louis B. Meyer (Arliss Howard), manufactured some consent in order to crush the the Socialist gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair (a cameoing Bill Nye), forging in him a blinding hot hatred of Hollywood as as place where destructive lies were made that contributed to his drinking problem and his ostracism from polite society.

Even putting it that way makes Mank feel a bit more steady on its feet than is the case: there's really no way at all in which all of this comes together smoothly to provide anything like a clear narrative. It's just a whirlwind of stuff, anchored solely by a solid cast that preserves the integrity of the characters from scene to scene; this includes some actively great performances, like Seyfried's perfect embodiment of period-correct accent work and physicality with strong insights into how Davies allowed Hearst to swamp her very real talent and screen presence, and it includes some that are merely steady and functional, but in a way that helps glue the film together, like Joseph Cross's descent from boyish enthusiasm as screenwriter Charles Lederer.

The strong cast at least keeps Mank feeling like a containable object that can be watched; the script is a busy mess of plot threads that don't go into any depth about things like the interaction between Hollywood and politics, or who gets to count as a film's "author", or how powerlessness can drive a man to self-destruction as a way of claiming power over at least his own life. It just presents them as things that happen, and are united by the fact that all of them make Herman Mankiewicz extremely mad. And the film can't even get up a good head of rage, with such a grave, stifling tone that it's never really able to access its own emotions anyway. It's a lovely formal object, but hollow, and frankly a bit dull.

The Mank screenplay dates to the tail end of that period, when Jack Fincher, father of up-and-coming director David Fincher, wrote a biopic of Mankiewicz that was in large part derived from "Raising Kane". David, in finally completing his decades-long dream of bringing his father's script to life, has backed down on that aspect of the project a bit - not enough! There is still a final act (of, like, five or six - it is one hell of a cluttered film, with a great deal more plot than is good for it) that has substantial scenes of Welles (played here by Tom Burke as an impatient dilettante with no personal charisma; his is the worst performance in a generally well-acted ensemble) acting entitled and pissy in a way that certainly doesn't suggest any real affection for him, or Citizen Kane, or movie directors, or cinema. Still, there's no sense in which the "point" of Mank is to slam Welles and give all the credit for Kane to Mankiewicz - there's not really any point in the film where it becomes "the making of Citizen Kane" at all, or where we're meant to find this interesting because the protagonist was involved in the creation of the officially-anointed Best Movie Ever Made. Welles barely even registers as a character until near the end of the 132-minute film. It is much more a film about the thousand petty indignities of being a working screenwriter in Hollywood, and of the difficulty of preserving one's sense of moral optimism in any industry that depends as much as Hollywood does on the most unbridled form of capitalism.

My second response to Mank is to be blown away by how lush the production is. To begin with, the score by Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross is one of the year's very best, a nostalgic dive into period-appropriate motifs with a sharp modernist edge that keeps it from being just pastiche (though if it were just a pastiche, it would be the film's best). It's also a remarkably handsome film, between Donald Graham Burt's production design and Trish Summerville's costumes, which lovingly re-create Los Angeles in the late 1930s with more of an eye towards the glossy trappings of movies of the period than to placing us into living history. And Erik Messerschmidt's black-and-white cinematography is some of the most stupidly beautiful stuff of any movie from 2020, finding a way to make charcoal grey glow with a digital sheen, and reminding us that Fincher is one of the few directors who has historically given actual thought to how to embrace the characteristics of digital cameras rather than force them to pretend to be film cameras. The irony is that Mank's images are actually trying to mimic film in some ways, leading to a film that has been littered with digital "film scratches" and "cigarette burns, despite not actually looking even a little bit like it was shot in the '30s or '40s - not in the way that blacks and whites register, not in the way that it's blocked, not in the shot scales being favored.

And this gets to the awkward problem that, while Mank is incredibly beautiful, it's perhaps not beautiful in a productive way. The visuals tend to get in the way of the movie, especially all of those lush charcoal greys that took Fincher and Messerschmidt so much obvious work to set up, making it more than a little visually claustrophobic. It is, indeed, quite a gloomy film, not in the way of film noir (or the proto-noir found in Citizen Kane), but simply in a a mordant, heavy way, one in which every human interaction is freighted with solemnity. This is sort of the only way Fincher has made movies (ten years later, I still routinely think about Nick Davis's description of the cinematography in The Social Network: "like a state funeral for the family cat"), with an obsessive meticulousness and technical perfection that end up feeling a bit exhausting and airless, and this sometimes fits the material better than others. It fits Mank particularly badly, given its pervasive engagement with 1930s filmmaking norms; it ends up being something of a hybrid between the artificial snappiness of classical Hollywood and the glowering seriousness of a modern prestige film, an awfully clunky marriage indeed. It's most obvious in the dialogue: Mankiewicz was a major writer of bantering, prattling speech in the '30s, with a slightly bitter sense of wit that leads to lots of cutting one-liners and lively monologues in his work. Jack Fincher has made the reasonable choice to mimic that style of dialogue in Mank, leading to a very talky movie, but without the keen understanding of rhythm that made '30s movies clip by so well. This ends up sounding muddy and cluttered and slow, and the deliberately fuzzy soundtrack, mimicking '30s sound recording and mixing, doesn't help matters out.

This is all a lot of words without ever getting into the heart of Mank, but that's in part because I'm not sure what the heart of the movie even is. Obviously, it's Mankiewicz himself, played by Gary Oldman with a breezy raconteur's warmth, though he leans a bit too far into mushmouthed clichés when playing the writer's alcoholism; but I don't know if I confidentally say what about Mankiewicz. The script covers a lot of ideas in a lot of ways, but largely hinges on the back-and-forth contrast between two eras. One is 1939, when Mank, recovering from a car accident (that he didn't cause), tried to crank out a first draft of the Kane script with the help of a British amanuensis named Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), drawing from his years of history as a frequent guest of William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and Marion Hearst (Amanda Seyfried) at the former's monstrous white elephant of an estate in San Simeon to tell the story of a Hearst-like newspaper magnate with a heart of poison. The other is 1934, when Mank watched with disgust as Hollywood elites, including the slimy Louis B. Meyer (Arliss Howard), manufactured some consent in order to crush the the Socialist gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair (a cameoing Bill Nye), forging in him a blinding hot hatred of Hollywood as as place where destructive lies were made that contributed to his drinking problem and his ostracism from polite society.

Even putting it that way makes Mank feel a bit more steady on its feet than is the case: there's really no way at all in which all of this comes together smoothly to provide anything like a clear narrative. It's just a whirlwind of stuff, anchored solely by a solid cast that preserves the integrity of the characters from scene to scene; this includes some actively great performances, like Seyfried's perfect embodiment of period-correct accent work and physicality with strong insights into how Davies allowed Hearst to swamp her very real talent and screen presence, and it includes some that are merely steady and functional, but in a way that helps glue the film together, like Joseph Cross's descent from boyish enthusiasm as screenwriter Charles Lederer.

The strong cast at least keeps Mank feeling like a containable object that can be watched; the script is a busy mess of plot threads that don't go into any depth about things like the interaction between Hollywood and politics, or who gets to count as a film's "author", or how powerlessness can drive a man to self-destruction as a way of claiming power over at least his own life. It just presents them as things that happen, and are united by the fact that all of them make Herman Mankiewicz extremely mad. And the film can't even get up a good head of rage, with such a grave, stifling tone that it's never really able to access its own emotions anyway. It's a lovely formal object, but hollow, and frankly a bit dull.