Dancing on a string

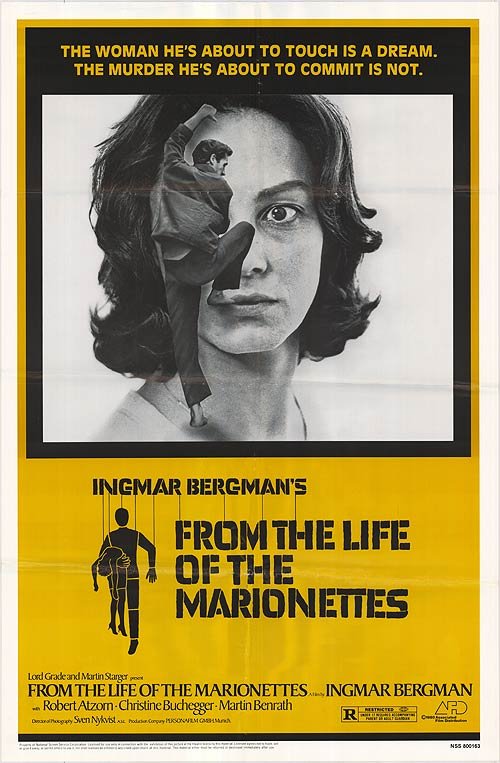

For what would prove to be the final film of his self-imposed exile in West Germany, Ingmar Bergman wanted to finally honor the cinema of his host country, rather than keep making quasi-Swedish chamber dramas as if nothing had changed but the address of his studio. And indeed, that is very much what he ended up with in the form of the 1980 telefilm From the Life of the Marionettes, with the important note that "German film", especially in the context of art cinema, tends to imply (for me, anyway), a certain heavy ugliness, a sordid viciousness of the spirit. Let us say, for this moment, that From the Life of the Marionettes perfectly lives up to that impression, while simultaneously demonstrating that German television in 1980 was way the fuck more permissive in what could be shown than I would ever have guessed plausible.

The film begins with the violent murder of a woman, portrayed without any kind of vulgar excess, but there's still no missing the ugliness and viciousness of the event, not least because it is one of only two scenes in the whole movie shot in color (the other is the closing scene). And a very harsh, lurid color, too - all the usual '70s earthtones, but presented in a super-saturated mode. So the film is kind of making spectacle of the murder, but it's a disgusting, upsetting spectacle, devoid of any stylistic pleasure or exploitation flair. The rest of the movie is a non-linear inquiry into how and why this happened, presented in high-contrast black-and-white by Bergman's right-hand cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, in a bravura display of why his black-and-white, even at its most aggressively caustic and hard on the eye, has a kind of aesthetic sublimity that his color films simply do not possess, even at their best.

Anyway, the black-and-white tells us this is something of an official inquiry, and so does the typeface font used for the credits (the universal signifer of "serious, impersonal business" in movies), and so do the title cards that break up the film into its non-linear chunks, each of them situating us in time relative to the murder, which they almost all refer to in a straight-faced, sensationlising tone as the "Katastrophe". It's presented to us as a report from the police interrogator (Karl Heinz-Pelser) who exists within the movie but not of it, a non-character receiving information from the actual participants in the drama.

The most important of these are Peter Egermann (Robert Atzorn) and his wife Katarina (Christine Buchegger), a very unhappily married couple who share the names and miseries of the couple played by Bibi Anderson and Jan Malmsjö in the first episode of Scenes from a Marriage. Whether this necessarily means that they're the same characters, and this is a sequel, or a spin-off, or a parallel universe, I really can't say, thought it has always been the convention (encouraged by Bergman) to consider From the Life of the Marionettes as some manner of companion piece to the earlier series. It's not a comparison that flatters From the Life of the Marionettes at all, though it does at least help to direct our attention towards what the film is doing. That is to say, the plot may say, "this is a crime thriller", and the structure might say, "this is a fragmented, prismatic portrait of a dangerously psychotic man's fractured personality", and it is both of these things, but it is even more Bergman's latest chamber drama about the gulfs between two people. It's just that it is a chamber drama that has been twisted and broken and turned actively cruel rather than simply remaining icily neutral towards its characters. So a German chamber drama rather than a Swedish one.

The point being, From the Life of the Marionettes is ultimately just as much about the psychological toll of married life as Scenes from a Marriage, but in reverse: that series was about two people who needed to get divorced and build new lives apart to appreciate the positive impact they had in each other's lives; this film is about two people who stay together at almost immeasurable cost to their respective humanity. The thrust of the drama, once we've ironed everything out and figured out what comes in what order, is that Peter hates Katarina so much that he wishes that he could kill her; when a chance encounter with a prostitute named Ka (Rita Russek) presents itself, he vents all of his rage on her, shattering and defiling her body with a vile passionate hatred that we never actually see, behind the sullen meekness of his outward personality, we can only infer it from the fact that the act has been performed. It's a deeply hopeless and despondent and nihilistic film, maybe the only truly nihilistic film Bergman ever made; even something like Winter Light offers the possibility that in a godless, meaningless universe, there are still humans and human connection, even if the characters in that film end up rejecting and ruining those tie. From the Life of the Marionettes declares right from its title that Peter and Katarina and all the rest are bound up in a fatalistic universe that has already condemned them to their actions; his violent madness is suggested to be the inevitable outcome of a life that has been focused on self-hatred and repression, possibly of his homosexual urges, definitely of the healthy expression of any sexuality.

This is, at any rate, Bergman's most explicitly sexual film: there is a considerable amount of fairly leering nudity, Katarina's friend and colleague Tim (Walter Schmidinger) is an out gay man who has some psychosexual hang-ups of his own with both of the main characters, and basically every conflict at some point boils down to sexual inadequacy, generally Peter's. Which also makes it his most Freudian film, not that he was much of a Freudian filmmaker. All this sex on the brain goes a long way to explaining why From the Life of the Marionettes ends up feeling so exceptionally squalid; domestic violence and mutual loathing are upsetting enough to watch, but they become that much more visceral when they are mixed up with the visceral fleshiness of sex, nudity, talk of orgasms, and bitter lust.

This all makes the film wildly unpleasant, of course; Bergman certainly did not make fun movies, which is surely the one thing you know about him if you know anything, but he never made anything as purely rancid as this. He owned up to this, even claimed it was part of what it was so important to him to make the film and why he regarded it highly after it was finished - something he was not inclined to do. The film is blatantly therapeutic for the filmmaker, who was going through one of the most pitch-black periods of his life at the time, after four years away from Sweden (and this for a man who avowedly hated leaving his home country and throughout his life had a highly neurotic response to even little amounts of stress). While there's no indication that I know of that there was any particular sexual, romantic, or domestic element to his depression in the late '70s - his final marriage was, on the contrary, the only one of his life that was stable, outwardly pleasant, and not marked by a laundry-list of mistresses - he was certainly a bitter, angry, miserable man, and he was quite open about wanting to pour all of those negative feelings into a pungent cinematic form. Presenting the movie's own bleak, toxic emotions in avowedly sexual terms, and then making the most sexually graphic work of his career, was his way of making it suitably provocative and devastating for all the rest of us, I think. From the Life of the Marionettes is nasty as hell, but that nastiness has an inescapable power, and at least some of that power derives from its crude, almost animalistic vulgarity.

Whether this all adds up to "German" or not, there's no question that it feels awfully different from the best and best-known Bergman films. He was a filmmaker with a deep investment in psychology and (over-)articulating his characters thoughts about their emotions, as much as or more than the emotions themselves; while he had made films with sometimes profound emotionally affecting moments within them (including Scenes from a Marriage itself), there was always a sense in which we're meant to think our way into feeling those things. None of that here: while the film has a strong intellectual component, thanks to its austere style and unfriendly narrative structure, it hammers its horrors home on a gut level.

Plus, I'm just not sure if Bergman had it in him to make this a full-on psychological study. By the time he made the film, he spoke German fluently, but it was still a second language, and much as happened in his two English-language films, 1971's The Touch and 1977's The Serpent's Egg, one doesn't entirely get the feeling that he knew how to guide the actors to their emotional marks (it probably doesn't help matters that the all-German cast includes not a single actor he'd worked with in a movie before, an extraordinarily rare occurrence in his career). Atzorn, especially feels a bit bland an unfocused, which perhaps is a strategy for getting us to see how detached from himself and the world Peter has gotten; it wouldn't be the first time a director deliberately guided an actor to give a somewhat limp, empty performance for the sake of portraying his character as a soulless sociopath. Though it would be the first time for Bergman to do so. Buchegger is certainly better, or at least more conventionally good, than her co-star, though there's not very much nuance in her role: she quickly lands on a strategy of smiling without amusement to express her disgust and anger with Peter and the world, and while the film's stormy descent into wretchedness means that there are very few scenes where this is a bad approach, it ends up feeling very samey.

So no, From the Life of the Marionettes is not a fun watch, and in a lot of ways, it's not a particularly insightful watch, not in the ways one wants from Bergman. Yet something about it gripped me early and refused to let go. Perhaps it's that it's genuinely challenging to watch - not because it is unpleasant, but because it is so deliberately opaque about how we're to find our way into the story. This is unusual for the director, who typically liked to make his movies straightforward and digestible despite their heavy content. And perhaps it's because Nykvist's images are so compellingly ugly: the harsh whiteness of the cinematography makes the film feel like it's leaving us with nowhere to hide, no soothing aesthetic filter between us and the script; it is one of the most striking and unusual-looking films he shot for Bergman.

Perhaps it's just because even uncomfortable emotions can be powerful ones, and the film's savage intensity makes it hard to turn away. It's a provocation, alright, but a successful one; Bergman set out to make me feel as horrible as he did, and across the span of decades, he managed to do just that. Not something you want to experience everyday, and I have a hard time imagining anybody who would want to reach for this first when they were in the mood for some thorny art cinema, but having had the experience of confronting it face-to-face, I won't soon shake it.

The film begins with the violent murder of a woman, portrayed without any kind of vulgar excess, but there's still no missing the ugliness and viciousness of the event, not least because it is one of only two scenes in the whole movie shot in color (the other is the closing scene). And a very harsh, lurid color, too - all the usual '70s earthtones, but presented in a super-saturated mode. So the film is kind of making spectacle of the murder, but it's a disgusting, upsetting spectacle, devoid of any stylistic pleasure or exploitation flair. The rest of the movie is a non-linear inquiry into how and why this happened, presented in high-contrast black-and-white by Bergman's right-hand cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, in a bravura display of why his black-and-white, even at its most aggressively caustic and hard on the eye, has a kind of aesthetic sublimity that his color films simply do not possess, even at their best.

Anyway, the black-and-white tells us this is something of an official inquiry, and so does the typeface font used for the credits (the universal signifer of "serious, impersonal business" in movies), and so do the title cards that break up the film into its non-linear chunks, each of them situating us in time relative to the murder, which they almost all refer to in a straight-faced, sensationlising tone as the "Katastrophe". It's presented to us as a report from the police interrogator (Karl Heinz-Pelser) who exists within the movie but not of it, a non-character receiving information from the actual participants in the drama.

The most important of these are Peter Egermann (Robert Atzorn) and his wife Katarina (Christine Buchegger), a very unhappily married couple who share the names and miseries of the couple played by Bibi Anderson and Jan Malmsjö in the first episode of Scenes from a Marriage. Whether this necessarily means that they're the same characters, and this is a sequel, or a spin-off, or a parallel universe, I really can't say, thought it has always been the convention (encouraged by Bergman) to consider From the Life of the Marionettes as some manner of companion piece to the earlier series. It's not a comparison that flatters From the Life of the Marionettes at all, though it does at least help to direct our attention towards what the film is doing. That is to say, the plot may say, "this is a crime thriller", and the structure might say, "this is a fragmented, prismatic portrait of a dangerously psychotic man's fractured personality", and it is both of these things, but it is even more Bergman's latest chamber drama about the gulfs between two people. It's just that it is a chamber drama that has been twisted and broken and turned actively cruel rather than simply remaining icily neutral towards its characters. So a German chamber drama rather than a Swedish one.

The point being, From the Life of the Marionettes is ultimately just as much about the psychological toll of married life as Scenes from a Marriage, but in reverse: that series was about two people who needed to get divorced and build new lives apart to appreciate the positive impact they had in each other's lives; this film is about two people who stay together at almost immeasurable cost to their respective humanity. The thrust of the drama, once we've ironed everything out and figured out what comes in what order, is that Peter hates Katarina so much that he wishes that he could kill her; when a chance encounter with a prostitute named Ka (Rita Russek) presents itself, he vents all of his rage on her, shattering and defiling her body with a vile passionate hatred that we never actually see, behind the sullen meekness of his outward personality, we can only infer it from the fact that the act has been performed. It's a deeply hopeless and despondent and nihilistic film, maybe the only truly nihilistic film Bergman ever made; even something like Winter Light offers the possibility that in a godless, meaningless universe, there are still humans and human connection, even if the characters in that film end up rejecting and ruining those tie. From the Life of the Marionettes declares right from its title that Peter and Katarina and all the rest are bound up in a fatalistic universe that has already condemned them to their actions; his violent madness is suggested to be the inevitable outcome of a life that has been focused on self-hatred and repression, possibly of his homosexual urges, definitely of the healthy expression of any sexuality.

This is, at any rate, Bergman's most explicitly sexual film: there is a considerable amount of fairly leering nudity, Katarina's friend and colleague Tim (Walter Schmidinger) is an out gay man who has some psychosexual hang-ups of his own with both of the main characters, and basically every conflict at some point boils down to sexual inadequacy, generally Peter's. Which also makes it his most Freudian film, not that he was much of a Freudian filmmaker. All this sex on the brain goes a long way to explaining why From the Life of the Marionettes ends up feeling so exceptionally squalid; domestic violence and mutual loathing are upsetting enough to watch, but they become that much more visceral when they are mixed up with the visceral fleshiness of sex, nudity, talk of orgasms, and bitter lust.

This all makes the film wildly unpleasant, of course; Bergman certainly did not make fun movies, which is surely the one thing you know about him if you know anything, but he never made anything as purely rancid as this. He owned up to this, even claimed it was part of what it was so important to him to make the film and why he regarded it highly after it was finished - something he was not inclined to do. The film is blatantly therapeutic for the filmmaker, who was going through one of the most pitch-black periods of his life at the time, after four years away from Sweden (and this for a man who avowedly hated leaving his home country and throughout his life had a highly neurotic response to even little amounts of stress). While there's no indication that I know of that there was any particular sexual, romantic, or domestic element to his depression in the late '70s - his final marriage was, on the contrary, the only one of his life that was stable, outwardly pleasant, and not marked by a laundry-list of mistresses - he was certainly a bitter, angry, miserable man, and he was quite open about wanting to pour all of those negative feelings into a pungent cinematic form. Presenting the movie's own bleak, toxic emotions in avowedly sexual terms, and then making the most sexually graphic work of his career, was his way of making it suitably provocative and devastating for all the rest of us, I think. From the Life of the Marionettes is nasty as hell, but that nastiness has an inescapable power, and at least some of that power derives from its crude, almost animalistic vulgarity.

Whether this all adds up to "German" or not, there's no question that it feels awfully different from the best and best-known Bergman films. He was a filmmaker with a deep investment in psychology and (over-)articulating his characters thoughts about their emotions, as much as or more than the emotions themselves; while he had made films with sometimes profound emotionally affecting moments within them (including Scenes from a Marriage itself), there was always a sense in which we're meant to think our way into feeling those things. None of that here: while the film has a strong intellectual component, thanks to its austere style and unfriendly narrative structure, it hammers its horrors home on a gut level.

Plus, I'm just not sure if Bergman had it in him to make this a full-on psychological study. By the time he made the film, he spoke German fluently, but it was still a second language, and much as happened in his two English-language films, 1971's The Touch and 1977's The Serpent's Egg, one doesn't entirely get the feeling that he knew how to guide the actors to their emotional marks (it probably doesn't help matters that the all-German cast includes not a single actor he'd worked with in a movie before, an extraordinarily rare occurrence in his career). Atzorn, especially feels a bit bland an unfocused, which perhaps is a strategy for getting us to see how detached from himself and the world Peter has gotten; it wouldn't be the first time a director deliberately guided an actor to give a somewhat limp, empty performance for the sake of portraying his character as a soulless sociopath. Though it would be the first time for Bergman to do so. Buchegger is certainly better, or at least more conventionally good, than her co-star, though there's not very much nuance in her role: she quickly lands on a strategy of smiling without amusement to express her disgust and anger with Peter and the world, and while the film's stormy descent into wretchedness means that there are very few scenes where this is a bad approach, it ends up feeling very samey.

So no, From the Life of the Marionettes is not a fun watch, and in a lot of ways, it's not a particularly insightful watch, not in the ways one wants from Bergman. Yet something about it gripped me early and refused to let go. Perhaps it's that it's genuinely challenging to watch - not because it is unpleasant, but because it is so deliberately opaque about how we're to find our way into the story. This is unusual for the director, who typically liked to make his movies straightforward and digestible despite their heavy content. And perhaps it's because Nykvist's images are so compellingly ugly: the harsh whiteness of the cinematography makes the film feel like it's leaving us with nowhere to hide, no soothing aesthetic filter between us and the script; it is one of the most striking and unusual-looking films he shot for Bergman.

Perhaps it's just because even uncomfortable emotions can be powerful ones, and the film's savage intensity makes it hard to turn away. It's a provocation, alright, but a successful one; Bergman set out to make me feel as horrible as he did, and across the span of decades, he managed to do just that. Not something you want to experience everyday, and I have a hard time imagining anybody who would want to reach for this first when they were in the mood for some thorny art cinema, but having had the experience of confronting it face-to-face, I won't soon shake it.