Nightmare logic

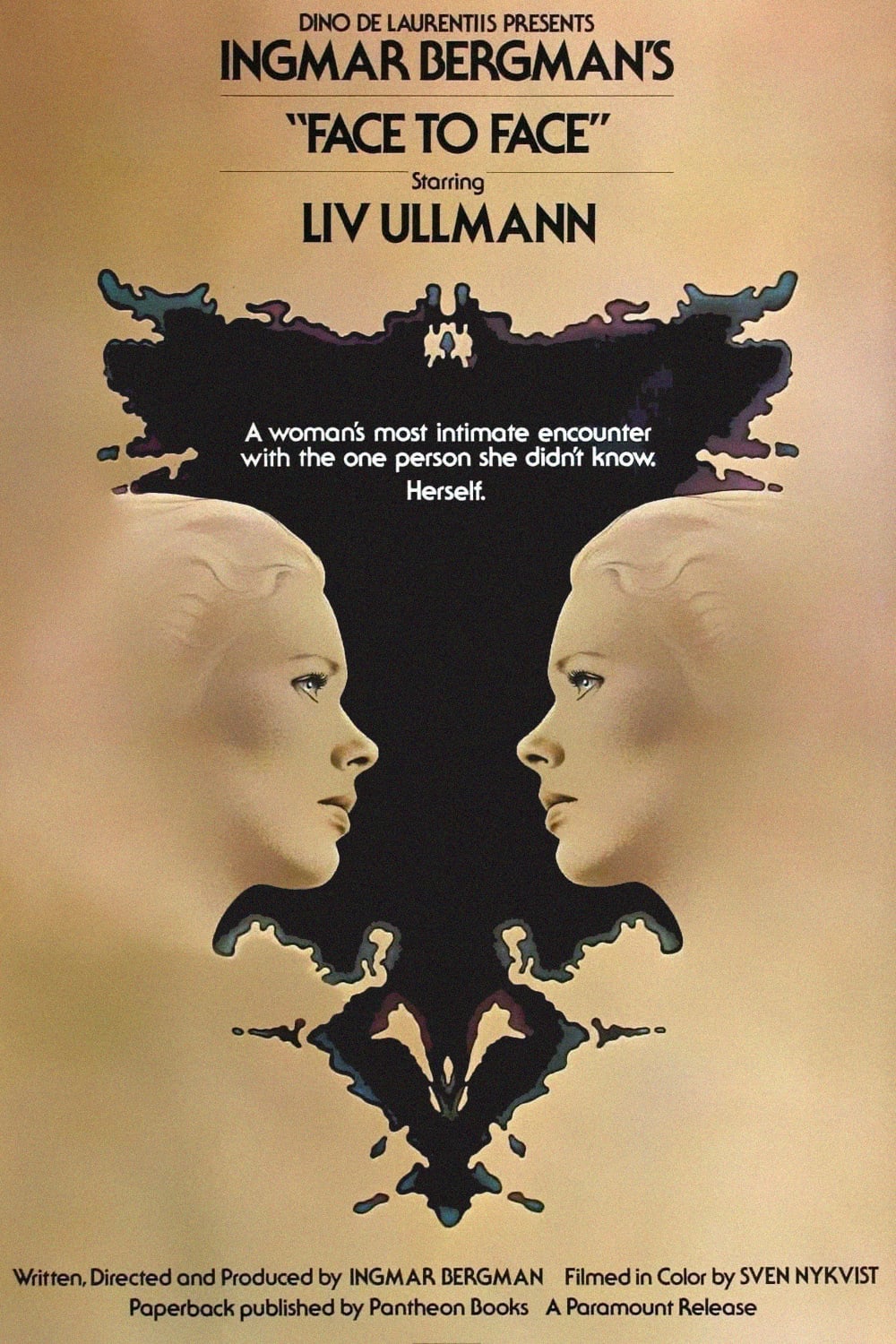

As we all know, Ingmar Bergman directed two television miniseries that were also cut down to feature length for theatrical release: Scenes from a Marriage and Fanny and Alexander. What is surely less-known is that, in between the two of them, he made another one. This is Face to Face, which aired on Swedish television as a four-part miniseries late in April, 1976 - a few weeks after it premiered as a theatrical feature in the United States, and a few weeks before it showed out of competition as a theatrical feature at the Cannes International Film Festival. As far as I have been able to suss out, that April broadcast was the only time the full four-part version of the series was ever seen, and that in Sweden as elsewhere in the world, Face to Face has only subsequently been known in its shortened form. Though how shortened? The are multiple cuts of the film, as short as 114 minutes and as long as 135, and I am not sure whether the one that played America in April was the same as the one that played Cannes in May, nor if either was the one I saw (which was 130 minutes, for the record; it is possible this is the 135-minute version with PAL speed-up applied*).

There are, I think, probably two main reasons for this vague proliferation of edits, and the general afterthought status the film seems to have, which I believe to be downstream from a complicated rights situation. One of these is that Bergman himself didn't think the film worked out: in his autobiography, he implies that the film's success at the Oscars - it was nominated for both Best Director and Best Actress, both extraordinary achievements for a film in a language other than English - was proof of how shallow and histrionic he'd allowed the material to get, and how much he'd betrayed Liv Ullmann's trust by asking her to go so embarrassingly big in her performance (he compared the film to Bob Hope's parody of Oscarbait acting at the end of Road to Morocco). But even if he'd been willing to help guide the film's post-Cannes path more directly, there was another reason he abandoned it: it came out shortly into the beginning of what might be the bleakest period of the director's entire professional career - certainly the darkest since he'd weathered the drought of the Swedish film industry in the early '50s. In January 1976, Bergman was arrested on charges of tax evasion, owing to the clumsy way he had his production company Cinematograph funnel money across international borders to pay foreign actors. By the end of March, he had been cleared of all charges, but between his depression-prone personality and tetchiness at having been, as he saw it, publicly humiliated, he declared that he would never again work in Sweden, fleeing his home to go into self-imposed exile in Germany. This had far uglier results than we have any need to get into right now, but I suspect that leaving Face to Face to fend for itself in limbo was collateral damage from this process.

Notwithstanding those Oscar nominations, I won't claim that it breaks my heart that Face to Face has become one of the hardest of Bergman's mature films to lay hands on. Were I to look for one pithy way to pin down what the film feels like, I'd say that it's what happens when a man given to neuroticism suddenly finds himself swimming in widely-praised commercial hits - the basically unprecedented box office success of Cries and Whispers leading right into the massive TV audience of Scenes from a Marriage and thence to the highly successful New Years Day broadcast of the telefilm The Magic Flute in 1975 - and grows paralyzed by the fear that he might fuck something up, which of course means that he is all the likelier to do so. In this case, Face to Face is extremely obviously the thing you make when you just made Scenes from a Marriage and you don't want to re-make it exactly, but you sure do hope that everybody who loved that one will love this one just as much, and for pretty much the same reasons. It even, somehow, found Bergman throwing his lot in with producer Dino De Laurentiis, exactly the man you want on your side if you're looking to make the same thing that was a big hit, only make it just a tiny bit different.

So we start with the most obvious thing to re-create: Face to Face is another story that puts Ullmann and Erland Josephson into long scenes and long takes where they discuss serious concepts at great length using very dense vocabulary and layered sentences. The dynamic is different; this isn't a two-hander, for one thing, but a deep dive into character psychology, built around Ullmann's character, a psychiatrist named Dr. Jenny Isaksson. Jenny has, of late, been suffering from anxiety, with her husband out of the country and her daughter Anna (Helene Friberg, so vivid as the girl in the audience of The Magic Flute) off the camp; making matters worse, she's staying with her grandparents (Aino Taube and Gunnar Björnstrand), who raised her after her parents died, and she's specifically staying in her teenage bedroom, and this is kicking up a lot of traumatic memories. These manifest as nightmarish visions, including repeat visits from an old woman with a jet-black orb where one of her eyes should be (Tore Segelcke). Soon enough, nightmares aren't enough: Jenny is experiencing the instability and surreal horror of nightmares even during what appears to be her waking hours. She is, as we quickly discover, dealing with a whole lifetime of ignored and repressed emotions coming out all at once, however they might - coming face to face with herself, if you will, and I guess there's no reason not to.

The idea behind the film is pretty nifty: what happens when a psychiatrist starts to go mad? She has all the tools she needs to hide her breakdown from the world and herself, but also the tools to correctly diagnose what's going on in her brain, and there's something there, at least in the early run. Ullmann is at her best when she's teasing out small things implied in the script but not precisely stated, and this delicate war between Jenny-the-patient and Jenny-the-doctor is one of the finest of these small things. She, and by extension the film (for Face to Face is first and foremost an exercise in letting Ullmann show off what she can do) are in much worse shape when Jenny grows closer and closer to completely breaking down, generally in the form of big showy acting setpieces against Josephson, who plays Dr. Tomas Jacobi, the divorced MD whom Jenny may want to sleep with, and who in turn may want to sleep with her. These moments are all very strictly on the Scenes from a Marriage model: long takes of close-ups that focus intently on Ullmann's eyes as she works out complicated layers of feelings and thoughts before deciding which ones will make it all the way to her mouth. The difference is that in Face to Face, these moments often involve Ullmann going to 100% on screaming, wailing, thrashing, and weeping. And by all means, Ullmann can scream and wail with the best of them, but it's honestly a little bit silly and over-the-top, big melodramatic breast-beating in a film of such ruthless psychological realism that it has left no room for melodrama and doesn't know what to do with it. I'm bit astonished to find that I preferred Josephson to Ullmann in most of their scenes together, and not by an especially little margin: he's playing a person, she's playing a hysterical fit, and so he gets to anchor their interactions in grace notes, even things just as simple as the concerned crease in his brow when he listens to her.

Nothwithstanding Josephson's calming presence, Face to Face basically stumbles into a bad pattern in its second half, where every time it wants to do something to really dive deep into Jenny's head, it does so with such messy enthusiasm that it ends up cheapening the moment, rather than giving it weight. We know from Cries and Whispers that Bergman can direct scenes of people screeching primal rage out of their body and have it feel psychologically acute; what exactly went wrong here I'd have a tough time saying.

Because it's certainly not the case that all of the film is bad; much of it is, in fact, very good. The story of aging and decrepitude that is silently expressed in the scenes with Taube and Björnstrand (the latter imposing despite doing very little other than remaining quiet in a very meaningful, somber way) is potent and troubling, and Ullmann's interaction with those actors speaks both to her character's affection for them but also her terror of ending up where they are. The nightmare sequences are also, generally speaking, quite strong, with the appearances of the one-eyed woman probably the best thing the film has on offer - horror was not Bergman's "thing", but he did a great job of weaponising it in tiny doses to give little punches of visceral terror to the more typical psychological drama material. And while the film is nowhere near Sven Nykvist's best work of cinematography - it suffers from really leaning into the '70s "hey, don't you just love brown?" aesthetic - he's doing fine work in capturing the voids of blackness that make the nightmarish spaces feel so vivid, and contrasting those with the crushing drabness of the waking world.

The film works, this is all to say. But it definitely works less than the films immediately preceding it, and it inaugurates a brief but impressively strong decline in Bergman's aesthetic fortunes. We have here the first time since the '50s where really feels like the director is working entirely on autopilot, and while it's too bad for historical reasons that it's so hard to scrounge up - and even worse that the miniseries version has apparently been fully buried - this is certainly not a particularly admirable exemplar of Bergman's strengths, even though it's attuned in every way to his characteristic interests.

*This is hardly the place to talk about PAL vs NTSC and other fun things to do with video standards, but if you don't know what PAL speed-up is, just be aware that it's the reason that European home video releases in standard definition run 4% faster than they should.

There are, I think, probably two main reasons for this vague proliferation of edits, and the general afterthought status the film seems to have, which I believe to be downstream from a complicated rights situation. One of these is that Bergman himself didn't think the film worked out: in his autobiography, he implies that the film's success at the Oscars - it was nominated for both Best Director and Best Actress, both extraordinary achievements for a film in a language other than English - was proof of how shallow and histrionic he'd allowed the material to get, and how much he'd betrayed Liv Ullmann's trust by asking her to go so embarrassingly big in her performance (he compared the film to Bob Hope's parody of Oscarbait acting at the end of Road to Morocco). But even if he'd been willing to help guide the film's post-Cannes path more directly, there was another reason he abandoned it: it came out shortly into the beginning of what might be the bleakest period of the director's entire professional career - certainly the darkest since he'd weathered the drought of the Swedish film industry in the early '50s. In January 1976, Bergman was arrested on charges of tax evasion, owing to the clumsy way he had his production company Cinematograph funnel money across international borders to pay foreign actors. By the end of March, he had been cleared of all charges, but between his depression-prone personality and tetchiness at having been, as he saw it, publicly humiliated, he declared that he would never again work in Sweden, fleeing his home to go into self-imposed exile in Germany. This had far uglier results than we have any need to get into right now, but I suspect that leaving Face to Face to fend for itself in limbo was collateral damage from this process.

Notwithstanding those Oscar nominations, I won't claim that it breaks my heart that Face to Face has become one of the hardest of Bergman's mature films to lay hands on. Were I to look for one pithy way to pin down what the film feels like, I'd say that it's what happens when a man given to neuroticism suddenly finds himself swimming in widely-praised commercial hits - the basically unprecedented box office success of Cries and Whispers leading right into the massive TV audience of Scenes from a Marriage and thence to the highly successful New Years Day broadcast of the telefilm The Magic Flute in 1975 - and grows paralyzed by the fear that he might fuck something up, which of course means that he is all the likelier to do so. In this case, Face to Face is extremely obviously the thing you make when you just made Scenes from a Marriage and you don't want to re-make it exactly, but you sure do hope that everybody who loved that one will love this one just as much, and for pretty much the same reasons. It even, somehow, found Bergman throwing his lot in with producer Dino De Laurentiis, exactly the man you want on your side if you're looking to make the same thing that was a big hit, only make it just a tiny bit different.

So we start with the most obvious thing to re-create: Face to Face is another story that puts Ullmann and Erland Josephson into long scenes and long takes where they discuss serious concepts at great length using very dense vocabulary and layered sentences. The dynamic is different; this isn't a two-hander, for one thing, but a deep dive into character psychology, built around Ullmann's character, a psychiatrist named Dr. Jenny Isaksson. Jenny has, of late, been suffering from anxiety, with her husband out of the country and her daughter Anna (Helene Friberg, so vivid as the girl in the audience of The Magic Flute) off the camp; making matters worse, she's staying with her grandparents (Aino Taube and Gunnar Björnstrand), who raised her after her parents died, and she's specifically staying in her teenage bedroom, and this is kicking up a lot of traumatic memories. These manifest as nightmarish visions, including repeat visits from an old woman with a jet-black orb where one of her eyes should be (Tore Segelcke). Soon enough, nightmares aren't enough: Jenny is experiencing the instability and surreal horror of nightmares even during what appears to be her waking hours. She is, as we quickly discover, dealing with a whole lifetime of ignored and repressed emotions coming out all at once, however they might - coming face to face with herself, if you will, and I guess there's no reason not to.

The idea behind the film is pretty nifty: what happens when a psychiatrist starts to go mad? She has all the tools she needs to hide her breakdown from the world and herself, but also the tools to correctly diagnose what's going on in her brain, and there's something there, at least in the early run. Ullmann is at her best when she's teasing out small things implied in the script but not precisely stated, and this delicate war between Jenny-the-patient and Jenny-the-doctor is one of the finest of these small things. She, and by extension the film (for Face to Face is first and foremost an exercise in letting Ullmann show off what she can do) are in much worse shape when Jenny grows closer and closer to completely breaking down, generally in the form of big showy acting setpieces against Josephson, who plays Dr. Tomas Jacobi, the divorced MD whom Jenny may want to sleep with, and who in turn may want to sleep with her. These moments are all very strictly on the Scenes from a Marriage model: long takes of close-ups that focus intently on Ullmann's eyes as she works out complicated layers of feelings and thoughts before deciding which ones will make it all the way to her mouth. The difference is that in Face to Face, these moments often involve Ullmann going to 100% on screaming, wailing, thrashing, and weeping. And by all means, Ullmann can scream and wail with the best of them, but it's honestly a little bit silly and over-the-top, big melodramatic breast-beating in a film of such ruthless psychological realism that it has left no room for melodrama and doesn't know what to do with it. I'm bit astonished to find that I preferred Josephson to Ullmann in most of their scenes together, and not by an especially little margin: he's playing a person, she's playing a hysterical fit, and so he gets to anchor their interactions in grace notes, even things just as simple as the concerned crease in his brow when he listens to her.

Nothwithstanding Josephson's calming presence, Face to Face basically stumbles into a bad pattern in its second half, where every time it wants to do something to really dive deep into Jenny's head, it does so with such messy enthusiasm that it ends up cheapening the moment, rather than giving it weight. We know from Cries and Whispers that Bergman can direct scenes of people screeching primal rage out of their body and have it feel psychologically acute; what exactly went wrong here I'd have a tough time saying.

Because it's certainly not the case that all of the film is bad; much of it is, in fact, very good. The story of aging and decrepitude that is silently expressed in the scenes with Taube and Björnstrand (the latter imposing despite doing very little other than remaining quiet in a very meaningful, somber way) is potent and troubling, and Ullmann's interaction with those actors speaks both to her character's affection for them but also her terror of ending up where they are. The nightmare sequences are also, generally speaking, quite strong, with the appearances of the one-eyed woman probably the best thing the film has on offer - horror was not Bergman's "thing", but he did a great job of weaponising it in tiny doses to give little punches of visceral terror to the more typical psychological drama material. And while the film is nowhere near Sven Nykvist's best work of cinematography - it suffers from really leaning into the '70s "hey, don't you just love brown?" aesthetic - he's doing fine work in capturing the voids of blackness that make the nightmarish spaces feel so vivid, and contrasting those with the crushing drabness of the waking world.

The film works, this is all to say. But it definitely works less than the films immediately preceding it, and it inaugurates a brief but impressively strong decline in Bergman's aesthetic fortunes. We have here the first time since the '50s where really feels like the director is working entirely on autopilot, and while it's too bad for historical reasons that it's so hard to scrounge up - and even worse that the miniseries version has apparently been fully buried - this is certainly not a particularly admirable exemplar of Bergman's strengths, even though it's attuned in every way to his characteristic interests.

*This is hardly the place to talk about PAL vs NTSC and other fun things to do with video standards, but if you don't know what PAL speed-up is, just be aware that it's the reason that European home video releases in standard definition run 4% faster than they should.