Original gangster

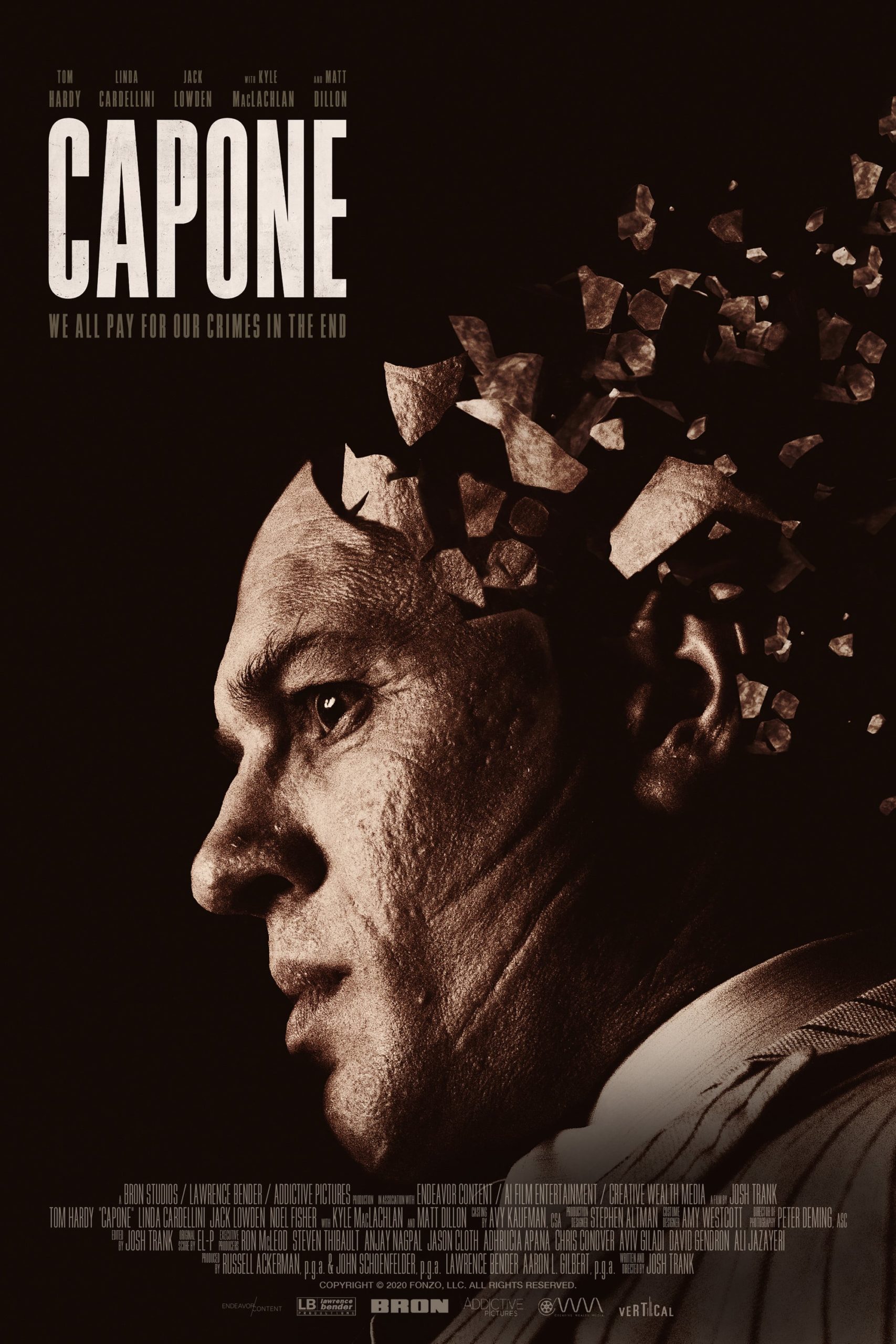

Capone is an outright disaster, but it's my favorite kind of outright disaster: ones that come from a mortifying surfeit of ambition and creativity. This is the third feature in the short but tumultuous career of writer-director Josh Trank, of the pleasantly clever and low-key Chronicle in 2012, and very much more visibly the farrago that was the 2015 Fantastic Four, a once-in-a-lifetime kind of dramatically mishandled production that threatened to end Trank's career right then and there. Capone is thus laden with the weight of being, not just Trank's follow-up to a widely-despised film, but his attempt to prove that he ought to be allowed to make movies at all. Maybe that's the reason it feels so aggressively show-offy, and maybe it has nothing to do with anything, but the film certainly has a reek of "look at me!" desperation in the aggressive flourishes of narrative style that make this not just a run-of-the-mill biopic; it is an unpleasant and hyperactive biopic.

The film takes for granted that you know who infamous Chicago gangster Alphonse Capone (Tom Hardy) was, and provides just enough exposition to let us know that we're meeting him in the final months of his life, by which point he has been remanded to his family in Palm Island, Florida by the federal government as his body and mind decay into oblivion thanks to the syphilis that had been his companion for his entire adult life. A rotten corpse at the age of 47, Capone is still reasonably articulate when we pick up with him, but suffering from hallucinations of himself as a child, as well as the many people he was involved in murdering, along with more general-purpose hallucinations, such as when he joins Louis Armstrong (Troy Warren Anderson) onstage to duet on "Blueberry Hill".

The latter detail I hope gets us to the point, which is that Capone is a fucking loopy movie. Even the "straight" version of the plot is bizarre: the last two months of Capone's life as his body shuts down and his brain melts, overseen by his despondent wife Mae (Linda Cardellini) and their children, while the FBI stubbornly watches him in the hopes that somewhere in his deterioration, he might still have the lucidity to remember where he stashed an alleged $10 million nest egg. Biopics do not do this; even the ones that focus on just a short passage of the subject's life usually choose to focus on something extremely interesting that they did, or that happened to them. Capone's depiction of Al Capone's life is positively perverse in how it skips over all the things that are actually dramatic to meet him when most of his personality has already been lost to the disease. While there are flashes of his guilt (or lack thereof) that explode through his syphilitic mind, the narrative arc of the movie is about how he goes from bad to worse as his body fails. This isn't the first such movie - right away, I can think of Steve McQueen's Hunger and Albert Serra's The Death of Louis XIV as doing basically the same thing, although they are both doing it better - but it's still pretty startling to see it, especially in the context of a movie that never feels like it's "doing" art cinema the way those other examples are.

The film is basically an attempt to literalise the disorientation of Capone's mind by making a film that functions as an achronological collage of partial memories. It's a bold, brave thing to do, and it's not less bold nor brave just because it's a messy failure. Trank immediately loses the thread of what he's doing, basically from the moment that Capone sees his junior self, and the film only gets more random and indulgent from there, growing really, really weird as it brings in the character of Johnny, played by Matt Dillon, a twitchy and big performance of a character who is, I think, the catch-all embodiment of all the death and destruction Capone caused over his career. And then there's a finale in which... well, that would be spoiling it, but it's where Trank finally uses gangster film imagery, a kind of jokeless parody of the 1983 Scarface (a copy of a copy of Capone), both to finally indulge the viewer's desire to see a proper Capone movie while also reinforce how much of a gangster picture this isn't.

Anyway, the film's sloppy ambition is bracing, but it's howling into a void. I can explain what Capone is, and I think I can explain what ideas it's trying to play with, but I cannot explain why. If one wants to make a film about the degradation of the human body, that's all well and good, but what in God's name is the point of making it about Al Capone? The Death of Louis XIV showed us the death of Louis XIV in minute, ugly detail as a way of stripping back the power of a king, revealing the sick flesh of a human, and it's certainly easy to imagine a film doing the same with history's most iconic gangster, depriving him of his aura of larger-than-life villainy to reveal the sad, miserable little man underneath. Capone doesn't do that - it doesn't not do that, to be fair. It mostly doesn't really care about Capone's past, except insofar as it's something to bleed into his present.

The script doesn't have a center, then; if the film, in contrast, does have a center, it's Hardy's performance, which is... well, it's definitely committed. It's a committed movie - nobody, from Trank to production designer Stephen Altman to composer El-P (writing his first movie score, a morbidly droning thing, and I hope he gets more opportunities, because it's the best thing here) is leaving anything on the table in making this the most possible version of itself. But Hardy is still on another level than everybody else, right from the moment he opens his mouth and some unfathomable gravelly, phlegmy screech rattles out of his throat. Every word he says made me wince in sympathetic pain, as well as just plain normal pain (when he sings "Blueberry Hill", it is the most genuinely dumbfounding thing I have seen in a movie in 2020), and then there's his physical performance to go along with it. Aided by some revolting make-up that leaves him cadaverous and clammy, Hardy goes all-in on portraying Capone as a rotting mound of flesh, with every movement an anguished labor, as he hangs his mouth open limply and grunts his way through every interaction, or even just as he looks out at the world. He throws himself into pantomiming a scene of Capone shitting his pants like he's Atlas hoisting the world up on his shoulders.

I cannot begin to tell you if this is good - I think it is not, but I also think that it's gripping and awe-inspiring in ways much more sedate and rational acting would have little hope of being. And that goes for the whole movie: it is such a bravura act that one is kind of sidetracked from noticing what a deranged, horribly unpleasant boondoggle it is. I mean, we are watching a film whose plot is, in its entirety "guy dies horribly". It is a film with an epic pants-shitting scene. It unquestionably has grandeur, though it is a kind of appalling, negative-imprint version of grandeur, where we are watching something misguided being done as fervently as possible. It's pretty clear proof that Josh Trank has no goddamn clue what movies should be, but at the same time, it's astonishing and memorable on a level movies of this sort almost never are, and God forgive me, but I hope he's able to find some recklessly stupid producer who'll let him make more just like it.

The film takes for granted that you know who infamous Chicago gangster Alphonse Capone (Tom Hardy) was, and provides just enough exposition to let us know that we're meeting him in the final months of his life, by which point he has been remanded to his family in Palm Island, Florida by the federal government as his body and mind decay into oblivion thanks to the syphilis that had been his companion for his entire adult life. A rotten corpse at the age of 47, Capone is still reasonably articulate when we pick up with him, but suffering from hallucinations of himself as a child, as well as the many people he was involved in murdering, along with more general-purpose hallucinations, such as when he joins Louis Armstrong (Troy Warren Anderson) onstage to duet on "Blueberry Hill".

The latter detail I hope gets us to the point, which is that Capone is a fucking loopy movie. Even the "straight" version of the plot is bizarre: the last two months of Capone's life as his body shuts down and his brain melts, overseen by his despondent wife Mae (Linda Cardellini) and their children, while the FBI stubbornly watches him in the hopes that somewhere in his deterioration, he might still have the lucidity to remember where he stashed an alleged $10 million nest egg. Biopics do not do this; even the ones that focus on just a short passage of the subject's life usually choose to focus on something extremely interesting that they did, or that happened to them. Capone's depiction of Al Capone's life is positively perverse in how it skips over all the things that are actually dramatic to meet him when most of his personality has already been lost to the disease. While there are flashes of his guilt (or lack thereof) that explode through his syphilitic mind, the narrative arc of the movie is about how he goes from bad to worse as his body fails. This isn't the first such movie - right away, I can think of Steve McQueen's Hunger and Albert Serra's The Death of Louis XIV as doing basically the same thing, although they are both doing it better - but it's still pretty startling to see it, especially in the context of a movie that never feels like it's "doing" art cinema the way those other examples are.

The film is basically an attempt to literalise the disorientation of Capone's mind by making a film that functions as an achronological collage of partial memories. It's a bold, brave thing to do, and it's not less bold nor brave just because it's a messy failure. Trank immediately loses the thread of what he's doing, basically from the moment that Capone sees his junior self, and the film only gets more random and indulgent from there, growing really, really weird as it brings in the character of Johnny, played by Matt Dillon, a twitchy and big performance of a character who is, I think, the catch-all embodiment of all the death and destruction Capone caused over his career. And then there's a finale in which... well, that would be spoiling it, but it's where Trank finally uses gangster film imagery, a kind of jokeless parody of the 1983 Scarface (a copy of a copy of Capone), both to finally indulge the viewer's desire to see a proper Capone movie while also reinforce how much of a gangster picture this isn't.

Anyway, the film's sloppy ambition is bracing, but it's howling into a void. I can explain what Capone is, and I think I can explain what ideas it's trying to play with, but I cannot explain why. If one wants to make a film about the degradation of the human body, that's all well and good, but what in God's name is the point of making it about Al Capone? The Death of Louis XIV showed us the death of Louis XIV in minute, ugly detail as a way of stripping back the power of a king, revealing the sick flesh of a human, and it's certainly easy to imagine a film doing the same with history's most iconic gangster, depriving him of his aura of larger-than-life villainy to reveal the sad, miserable little man underneath. Capone doesn't do that - it doesn't not do that, to be fair. It mostly doesn't really care about Capone's past, except insofar as it's something to bleed into his present.

The script doesn't have a center, then; if the film, in contrast, does have a center, it's Hardy's performance, which is... well, it's definitely committed. It's a committed movie - nobody, from Trank to production designer Stephen Altman to composer El-P (writing his first movie score, a morbidly droning thing, and I hope he gets more opportunities, because it's the best thing here) is leaving anything on the table in making this the most possible version of itself. But Hardy is still on another level than everybody else, right from the moment he opens his mouth and some unfathomable gravelly, phlegmy screech rattles out of his throat. Every word he says made me wince in sympathetic pain, as well as just plain normal pain (when he sings "Blueberry Hill", it is the most genuinely dumbfounding thing I have seen in a movie in 2020), and then there's his physical performance to go along with it. Aided by some revolting make-up that leaves him cadaverous and clammy, Hardy goes all-in on portraying Capone as a rotting mound of flesh, with every movement an anguished labor, as he hangs his mouth open limply and grunts his way through every interaction, or even just as he looks out at the world. He throws himself into pantomiming a scene of Capone shitting his pants like he's Atlas hoisting the world up on his shoulders.

I cannot begin to tell you if this is good - I think it is not, but I also think that it's gripping and awe-inspiring in ways much more sedate and rational acting would have little hope of being. And that goes for the whole movie: it is such a bravura act that one is kind of sidetracked from noticing what a deranged, horribly unpleasant boondoggle it is. I mean, we are watching a film whose plot is, in its entirety "guy dies horribly". It is a film with an epic pants-shitting scene. It unquestionably has grandeur, though it is a kind of appalling, negative-imprint version of grandeur, where we are watching something misguided being done as fervently as possible. It's pretty clear proof that Josh Trank has no goddamn clue what movies should be, but at the same time, it's astonishing and memorable on a level movies of this sort almost never are, and God forgive me, but I hope he's able to find some recklessly stupid producer who'll let him make more just like it.