Touching me, touching you

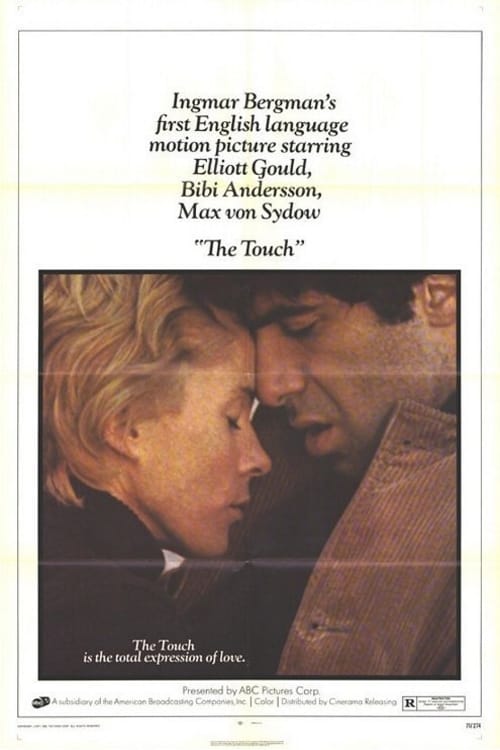

It is very often the case that film directors are terrible judges of their own art, both qualitatively (was this good or bad?) and descriptively (why does this work the way it does?). Not so with Ingmar Bergman. Almost without exception, when he said that one of his films was bad, it was bad, and generally for exactly the reasons he thought it was. And boy, did he ever think that The Touch was bad - his worst film ever, even (it's not. But it is certainly worse than he should have been capable of at this point in his career).

The film was his first production in English, which is part of it; in his memoirs, the director complained that of the two versions he shot, the all-English version that had become the primary cut of the film in circulation by the mid-'70s was considerably worse, uncertain nonsense that left the actors lost without a net. I do not know when that changed; the version of The Touch that's by far the easiest to see now preserves the original intention that conversations between Swedish characters were in Swedish, conversations between Swedes and Americans in English. That's how I saw it, and good Lord, if this is the better version...

But let us immediately dispense with the notion that the problem with The Touch is that the people making it struggled with English. This is, for one thing, not all that big of a problem; there are certain tortured verbal expressions that I suspect would feel better if I was reading them than listening to them, but the dialogue is generally no worse than functional, except in those moments when it turns excessively flowery and sentimental, and that's a problem The Touch has on other levels than the writing. On top of this, one of the native speakers of Swedish in the cast, Bibi Andersson, is up to some really excellent work - part of the reason Bergman brought her into this project that he already felt was doomed was because of her strong command of English, in addition to having a friendly face he could rely on. She turns out to be very much the bright spot of The Touch and close to the only reason it's really worth bothering with it, somehow finding her way into the desperate beating heart of a woman who is written in a frankly rather muddled way. It's a worthy climax to her collaboration with Bergman: while this wasn't the last time they'd work together, it's the last time she got a really meaty, substantial role in one of his films, and it's gratifying that he was able, even in the ruins of this project, to give her a proper test of her talents, after not always having the best idea what to do with her in their work together (of all Bergman's top-tier acting collaborators, I'd say that Andersson had the lowest percentage of really juicy parts).

Andersson plays Karin Vergerus - a surname which was starting to bear quite a lot of weight in Bergman's filmography by this point, and of course Karin comes pre-loaded with all the symbolism of being the director's mother's name - who opens the film by rushing to the hospital in the small village where she lives, not quite making it there in time to say goodbye before her mother dies. Anticlimactically and rather awkwardly, she spends a moment with the corpse, and wanders back out to go to her pleasant, boring home, with her pleasant, boring children, and her pleasant, boring husband, Andreas (Max von Sydow). Meanwhile, she is spotted by American archaeologist David Kovac (Elliott Gould, a ludicrously obvious pick, in 1971, to be the American in Ingmar Bergman's first English-language film), who later pays a visit on the Vergerus home, to introduce himself as he roots around in their tiny community, but also to hit on Karin. Later, they have sex, several times, in multiple locations, and when not having sex they have meandering, soulful conversations. It turns out that David has an unsteady temper, and is prone to shouting and pouting, but also prone to poetic flights of passion, and this is enough for Karin to fall in love with him, after all these years of the unbelievably placid, unruffled Andreas.

Very early in the film's life, when it was starting to become clear that critics really disliked it and why, Andersson huffed and puffed at a press conference that it was horribly small-minded and insulting to dismiss The Touch as "banal", when it is in fact focused on the most powerful of human emotions, and that it speaks to the difficult truths that we cannot control who or how we love, and whatnot. Having thus been duly pre-shamed across nearly a half-century, may I offer my rebuttal: yes, but this is really fucking banal. Part of the issue is that the characters are muddled and under-thought. Andreas exists solely as a narrative problem to resolve, or not; it's considerably more than halfway into the movie (at 115 minutes, quite long for Bergman, and it's not time well spent) before he has literally anything to do other than be lightly befuddled. This was von Sydow's last appearance in a Bergman film, and let us say, he doesn't get the same kind of grand finale that Andersson gets; it is a remarkably dull part that offers him almost nothing to do, and it's a real shame to see such a fruitful collaboration end on such a wet fart of a character given so little life by a checked-out performance.

But at least von Sydow gets the film's best joke - and in its first hour, it is quite full of humor, some of it even funny - when he's flipping through photographic slides with the oblivious sincerity of a bad host, and clumsily notes that his mother-in-law has just died, when her photo shows up. Gould doesn't get shit. David is a complete failure of a character, coming across as a peevish brat more than anything else, and I am gravely concerned that Bergman thought this made him an attractive lead in a romantic drama. To be honest, I cannot fathom why the film believes that it's reasonable for Karin to fall for him: he's moody and belittling, unpleasantly prone to manic outbursts, and frankly a bit snotty. If the film meant for this to all play as somewhat tragic and uncomfortable - Karin being led by her libido more than her heart, or trapped by a sexist society, or just a big dummy who doesn't know what she's getting into - I could maybe see the point. But The Touch honestly seems to suppose that David is magnetic for reasons other than Gould's inherent movie star swagger. And even setting that aside - as if that wasn't three-quarters of the movie! - he's simply not a wholly formed character, spouting out a Holocaust backstory partway through the movie that informs nothing and doesn't get referenced again. The only thing does, in fact, is to severely imbalance a film that has been exclusively about personal emotions, and has no place whatsover to put the weight of the 20th Century's most horrifying moral catastrophe; it feels like a European art movie tic more than a legitimate storytelling decision.

Not the only place Bergman seems asleep at the switch, either. While there's no mistaking The Touch for anybody else's work - the glacial conversations and desperate close-ups are quintessential Bergman - it feels like some kind of horrid hybrid of his chamber dramas and the slick arthouse romantic dramas of the period, on the model of A Man and a Woman, and its tastefully tepid ilk. Certainly, there's no better way to explain what the hell is up with the music here, all limp, insipid romantic bleating - the first time in literally years that a Bergman film had anything really in the way of a musical score at all, so why now, and having decided that it had to be now, why this appalling weightless muzak cheerfully droning its bourgeois romantic clichés at us? The music is also the backbone of the film's single most indefensible moment, a gruesome "comic" montage of Karin preparing for a date with David, running in and out of her dressing room and every time, wearing a different outfit that she regards with outsized dismay in the mirror. Andersson commits to the bit, but it is a shitty bit, with the music goofily bouncing around (it has female vocalisations. They go "da-da-da") and the moment going on for a good three or four times the length it needs to make its point and wear out its charms. I write these words without the benefit of having seen every single film Bergman directed, so I cannot say that this is the worst scene of his entire career. But I can, and with great vehemence shall, say that its the worst scene of his entire career up to 1971.

Most of the film isn't acutely bad, like this, it's just shallow and unconvincing as a love story, failing to make its characters emerge as anything other than the stock types in any random early '70s adultery drama. Parts of it are actively good, thank God. Andersson is working hard to make Karin's ennui and romantic yearnings seem legitimate in the absence of all available evidence, and I actually do appreciate that the film has its wry, macabre sense of humor, the outfit montage notwithstanding. And Sven Nykvist's color cinematography here starts to feel focused and purposeful, finding a nice balance of lush saturation of objects that don't have all that much color to begin with, along with slightly high-contrast lighting to give everything just a bit more of an edge than the drowsily handsome exteriors would seem to have coming to them. It finds something hazily beautiful in the ugly brown-greys of early '70s cinematography, slightly too vivid and bright given how overcast everything feels. With hindsight to guide us, it very much feels like he's on the track that will immediately lead to Cries and Whispers, and after the not very interesting cinematography in The Passion of Anna, it's comforting to think that there's some underlying method to the visuals here. That's certainly not enough to make The Touch good, but it's enough to keep it from being as entirely dismal as, for example, the next film Bergman made in English...

The film was his first production in English, which is part of it; in his memoirs, the director complained that of the two versions he shot, the all-English version that had become the primary cut of the film in circulation by the mid-'70s was considerably worse, uncertain nonsense that left the actors lost without a net. I do not know when that changed; the version of The Touch that's by far the easiest to see now preserves the original intention that conversations between Swedish characters were in Swedish, conversations between Swedes and Americans in English. That's how I saw it, and good Lord, if this is the better version...

But let us immediately dispense with the notion that the problem with The Touch is that the people making it struggled with English. This is, for one thing, not all that big of a problem; there are certain tortured verbal expressions that I suspect would feel better if I was reading them than listening to them, but the dialogue is generally no worse than functional, except in those moments when it turns excessively flowery and sentimental, and that's a problem The Touch has on other levels than the writing. On top of this, one of the native speakers of Swedish in the cast, Bibi Andersson, is up to some really excellent work - part of the reason Bergman brought her into this project that he already felt was doomed was because of her strong command of English, in addition to having a friendly face he could rely on. She turns out to be very much the bright spot of The Touch and close to the only reason it's really worth bothering with it, somehow finding her way into the desperate beating heart of a woman who is written in a frankly rather muddled way. It's a worthy climax to her collaboration with Bergman: while this wasn't the last time they'd work together, it's the last time she got a really meaty, substantial role in one of his films, and it's gratifying that he was able, even in the ruins of this project, to give her a proper test of her talents, after not always having the best idea what to do with her in their work together (of all Bergman's top-tier acting collaborators, I'd say that Andersson had the lowest percentage of really juicy parts).

Andersson plays Karin Vergerus - a surname which was starting to bear quite a lot of weight in Bergman's filmography by this point, and of course Karin comes pre-loaded with all the symbolism of being the director's mother's name - who opens the film by rushing to the hospital in the small village where she lives, not quite making it there in time to say goodbye before her mother dies. Anticlimactically and rather awkwardly, she spends a moment with the corpse, and wanders back out to go to her pleasant, boring home, with her pleasant, boring children, and her pleasant, boring husband, Andreas (Max von Sydow). Meanwhile, she is spotted by American archaeologist David Kovac (Elliott Gould, a ludicrously obvious pick, in 1971, to be the American in Ingmar Bergman's first English-language film), who later pays a visit on the Vergerus home, to introduce himself as he roots around in their tiny community, but also to hit on Karin. Later, they have sex, several times, in multiple locations, and when not having sex they have meandering, soulful conversations. It turns out that David has an unsteady temper, and is prone to shouting and pouting, but also prone to poetic flights of passion, and this is enough for Karin to fall in love with him, after all these years of the unbelievably placid, unruffled Andreas.

Very early in the film's life, when it was starting to become clear that critics really disliked it and why, Andersson huffed and puffed at a press conference that it was horribly small-minded and insulting to dismiss The Touch as "banal", when it is in fact focused on the most powerful of human emotions, and that it speaks to the difficult truths that we cannot control who or how we love, and whatnot. Having thus been duly pre-shamed across nearly a half-century, may I offer my rebuttal: yes, but this is really fucking banal. Part of the issue is that the characters are muddled and under-thought. Andreas exists solely as a narrative problem to resolve, or not; it's considerably more than halfway into the movie (at 115 minutes, quite long for Bergman, and it's not time well spent) before he has literally anything to do other than be lightly befuddled. This was von Sydow's last appearance in a Bergman film, and let us say, he doesn't get the same kind of grand finale that Andersson gets; it is a remarkably dull part that offers him almost nothing to do, and it's a real shame to see such a fruitful collaboration end on such a wet fart of a character given so little life by a checked-out performance.

But at least von Sydow gets the film's best joke - and in its first hour, it is quite full of humor, some of it even funny - when he's flipping through photographic slides with the oblivious sincerity of a bad host, and clumsily notes that his mother-in-law has just died, when her photo shows up. Gould doesn't get shit. David is a complete failure of a character, coming across as a peevish brat more than anything else, and I am gravely concerned that Bergman thought this made him an attractive lead in a romantic drama. To be honest, I cannot fathom why the film believes that it's reasonable for Karin to fall for him: he's moody and belittling, unpleasantly prone to manic outbursts, and frankly a bit snotty. If the film meant for this to all play as somewhat tragic and uncomfortable - Karin being led by her libido more than her heart, or trapped by a sexist society, or just a big dummy who doesn't know what she's getting into - I could maybe see the point. But The Touch honestly seems to suppose that David is magnetic for reasons other than Gould's inherent movie star swagger. And even setting that aside - as if that wasn't three-quarters of the movie! - he's simply not a wholly formed character, spouting out a Holocaust backstory partway through the movie that informs nothing and doesn't get referenced again. The only thing does, in fact, is to severely imbalance a film that has been exclusively about personal emotions, and has no place whatsover to put the weight of the 20th Century's most horrifying moral catastrophe; it feels like a European art movie tic more than a legitimate storytelling decision.

Not the only place Bergman seems asleep at the switch, either. While there's no mistaking The Touch for anybody else's work - the glacial conversations and desperate close-ups are quintessential Bergman - it feels like some kind of horrid hybrid of his chamber dramas and the slick arthouse romantic dramas of the period, on the model of A Man and a Woman, and its tastefully tepid ilk. Certainly, there's no better way to explain what the hell is up with the music here, all limp, insipid romantic bleating - the first time in literally years that a Bergman film had anything really in the way of a musical score at all, so why now, and having decided that it had to be now, why this appalling weightless muzak cheerfully droning its bourgeois romantic clichés at us? The music is also the backbone of the film's single most indefensible moment, a gruesome "comic" montage of Karin preparing for a date with David, running in and out of her dressing room and every time, wearing a different outfit that she regards with outsized dismay in the mirror. Andersson commits to the bit, but it is a shitty bit, with the music goofily bouncing around (it has female vocalisations. They go "da-da-da") and the moment going on for a good three or four times the length it needs to make its point and wear out its charms. I write these words without the benefit of having seen every single film Bergman directed, so I cannot say that this is the worst scene of his entire career. But I can, and with great vehemence shall, say that its the worst scene of his entire career up to 1971.

Most of the film isn't acutely bad, like this, it's just shallow and unconvincing as a love story, failing to make its characters emerge as anything other than the stock types in any random early '70s adultery drama. Parts of it are actively good, thank God. Andersson is working hard to make Karin's ennui and romantic yearnings seem legitimate in the absence of all available evidence, and I actually do appreciate that the film has its wry, macabre sense of humor, the outfit montage notwithstanding. And Sven Nykvist's color cinematography here starts to feel focused and purposeful, finding a nice balance of lush saturation of objects that don't have all that much color to begin with, along with slightly high-contrast lighting to give everything just a bit more of an edge than the drowsily handsome exteriors would seem to have coming to them. It finds something hazily beautiful in the ugly brown-greys of early '70s cinematography, slightly too vivid and bright given how overcast everything feels. With hindsight to guide us, it very much feels like he's on the track that will immediately lead to Cries and Whispers, and after the not very interesting cinematography in The Passion of Anna, it's comforting to think that there's some underlying method to the visuals here. That's certainly not enough to make The Touch good, but it's enough to keep it from being as entirely dismal as, for example, the next film Bergman made in English...