Amicus Horror: Where wolf?

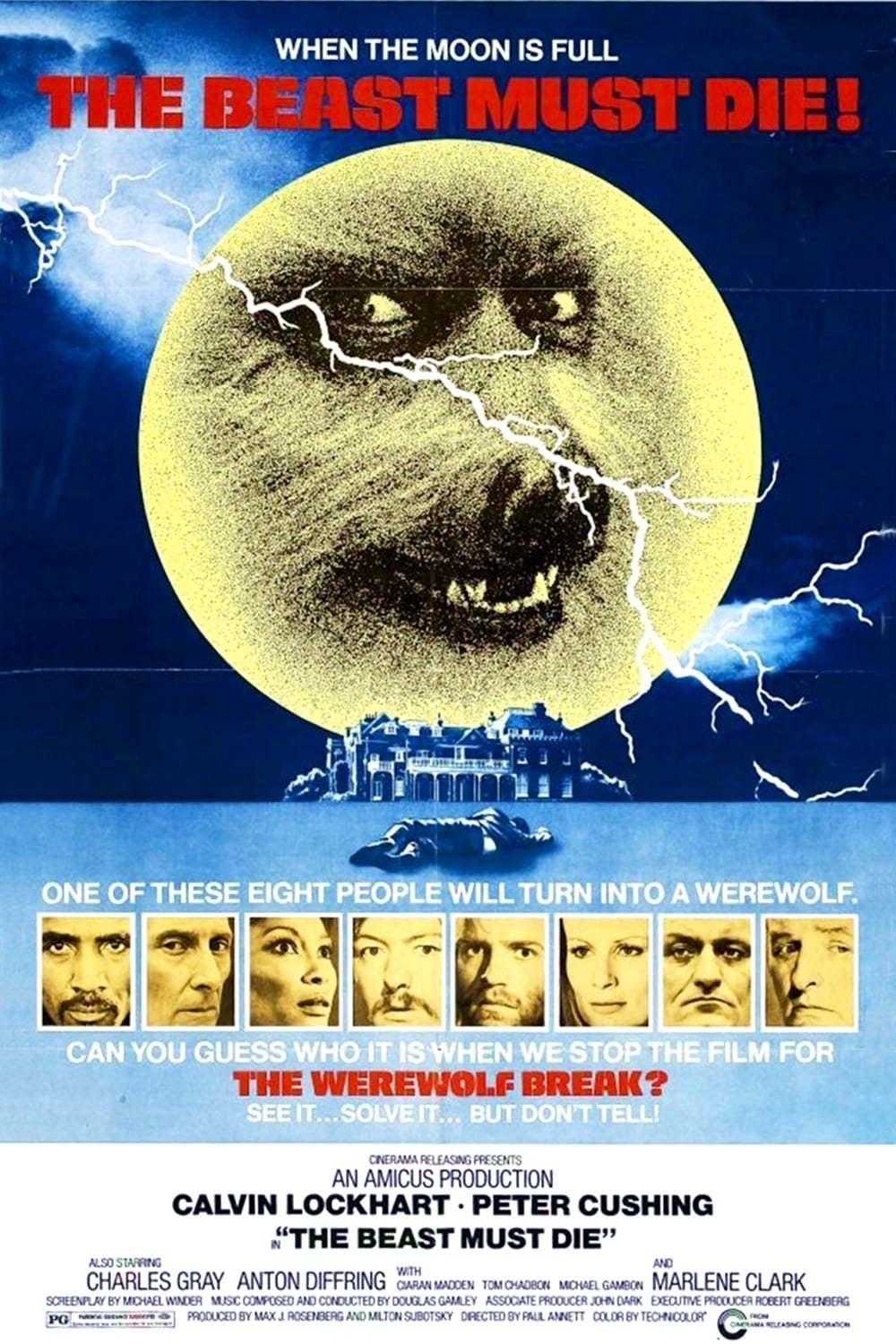

1974 is awfully damn late to be indulging in William Castle-style carnival barker tactics to sell a movie - that belongs to an age of cheesy B-movies, not an age of grim, violent grind house fodder. But that is, nonetheless, exactly what The Beast Must Die gets up to, over the vehement objections of its director, Paul Annett. Producer Milton Subotsky, who apparently hated the film and felt it needed some kind of sexing up, found that sexiness in the form of a thirty-second "Werewolf Break" right before the film's climax (which cannot help but recall the "Fright Break" from Castle's 1961 Homicidal). And what, pray tell, is a "Werewolf Break"? The film has foreshadowed it in a set of three title cards right at the start, narrated with maximum menace by Valentine Dyall:

"This film is a detective story--in which you are the detective."

"The question is not 'Who is the murderer?"--But 'Who is the werewolf?'"

"After all the clues have been shown--You will get a chance to give your answer."

And so we will be, as a giant stopwatch graphic hovers over the faces of the five remaining suspects (out of eight - two are dead, one has clearly been disqualified) in one of the downright goofiest whodunnits I have ever watched. To be clear, I have no objections to cross-breeding a werewolf movie and a murder mystery. It makes a kind of sense, even, as anyone who's ever played the party game Werewolf knows good and well. I don't even object to the Werewolf Break, which has an endearing kitschy quality, though I confess to being baffled by what the hook was supposed to be. Does everybody just start screaming their pick out loud in the theater? Did ushers come and take your vote? Was it a contest? Because if it was what it looks like, and it's just giving you the opportunity to quietly, in the privacy of your own brain, decide who you think the killer is, I'm pretty sure murder mysteries had already been doing that for decades by 1974, without needing to jam on the brakes right before the climax of the movie. This is, in fact, part of the reason we watch mysteries. But I suppose it's also possible that Subotsky was just mad at the movie, and wanted to punish it.

That would not be an inexplicable response. The Beast Must Die is, I regret to say, a pretty bad movie; it has terrible elements and mediocre elements, but not really any strong elements, unless you share my conviction that Peter Cushing doing literally anything whatsoever is good cinema. And if you share that conviction, The Beast Must Die is a pretty good way to test your faith, because he's really not up to anything here that he should be proud of.

The Beast Must Die tells us early how little we should expect, following up that playfully corny opening narration with a one-two punch of some hideous helicopter shots in all the flavors of grainy brown that mid-'70s film stock could muster up, accompanied by a score by Douglas Gamley that listlessly pipes in what I guess qualifies as "funk" by the standards of Great Britain in 1974. We move in close to the grounds of some sprawling estate, where a man in form-fitting black gear is stalking through the woods, apparently on the run from security forces operated by a different man in a room full of monitors. There's a horribly dispiriting "bargain basement spy thriller" vibe to all of it, with the music doing not a goddamn thing to make any of it better, but at least this turns out to be a fake-out: the man in black is Tom Newcliffe (Calvin Lockhart), the owner of the place, and he and his right-hand man Pavel (Anton Diffring) have been running tests on the security perimeter, readying for the event Tom is about to throw. This is a werewolf-hunting murder mystery party, we learn after a long amount of peek-a-boo writing that makes us wait for even the slowest of the characters to catch up before confirming that the film with a "Werewolf Break" has a werewolf in it. Tom is, among his many rich person hobbies, a big game hunter, and werewolves are the last frontier of big game; he has a lead on a possible lycanthrope, and has gathered the likeliest suspects to spend some time with he and his wife Caroline (Marlene Clark), who clearly thinks this whole thing is disgusting madness, and is plainly starting to re-evaluate how much her current lifestyle justifies being married to this insane person.

The guests/suspects are Arthur Bennington (Charles Gray), a former diplomat, now disgraced; Jan Gilmore (Michael Gambon), a surly pianist, and his wife Davina (Ciaran Madden); convicted cannibal Paul Foote (Tom Chabon), who declares with a kind of smirk that it was basically part of a med school prank, but doesn't deny it; and Dr. Christopher Lundgren (Cushing), a mild-mannered archaeologist who is one of the country's foremost amateur werewolf experts. For nearly all of the film's desperately slow-moving 92-minute film, we will watch Tom sit these people down and yell at them in various parlors, all of them shot with ugly flatness by Annett (a TV director making his first feature, and you can tell) and cinematographer Jack Hildyard (who had worked with David Lean and Alfred Hitchcock, and you can't tell), providing virtually no actual evidence for the audience to begin chewing over, in part because nothing has actually happened about which we can form an opinion one way or another. Eventually, we see the werewolf in action, and the very happy German Shepherd playing the murderous beast is, at least, more charismatic than any of the people who might have transformed into it.

The lack of active content, mixed together with the extremely cumbersome way that screenwriter Michael Winder (adapting a story by James Blish) handles the unnecessarily complicated exposition, would be all that it takes to make sure that The Beast Must Die would suck all the fun out of its hokey premise; the decayed brown palette muddying things up visually and the scattershot pacing (sometimes much too fast, as in the pre-guest exposition phase; more often much too slow, as when we stop on go-nowhere conversations that feel like they take up an entire reel) muddying things up narratively are just there for redundancy's sake. But despite all of that, I think I hate the acting worst, and not just because the film has forced me into a horrible confrontation with the reality that Cushing can be boring in a film, so committed to the clipped, mannered pattern of speech he's adopted for his character that he forgets to do anything but robotically puke out werewolf lore. He's still closer to being the best actor in the cast than the worst: the worst is obviously Lockhart, which is too bad given that he's also in the movie by far the most often. His performance is a deadly form of overly-enunciated hamminess, like something out of children's theater, making every bit of slack dialogue come across with florid, breathless urgency and gesturing with pantomime-like ferocity. It's weird and ineffectiveness to be curiously engaging, which I guess is more than anyone else can claim, but it's tiring. Meanwhile, Gray, Gambon, and Clark snooze their way through, Madden has a wild, deer-in-the-headlights star, and Chadbon is alone able to make something like a character out of this, largely because his snotty smartass with a shit-eating grin is the only person in the movie who gets to have any fun. Which seems like something more people in a werewolf murder mystery ought to be doing.

That lack of fun is pretty much the film's whole thing: it has neither real atmosphere nor energetic kitschiness, and it just kind of drags itself out, punishing us for having an interest in it. The weird novelty of the plot is different, at least, but mostly this feels like the worst of all worlds: too square for '70s horror, too glum and realist for a campy throwback. It's a bleak finale for the storied run of Amicus Productions horror films - this was the last of those movies produced by the studio, and the second-to-last released, and the only one that remained - Madhouse, from the same summer of '74 - was more of an American International Pictures production that Amicus happened to help out with. Still, it's pleasurable to consider that film to be the true Amicus finale; The Beast Must Die is a dull sack of crap that has been almost entirely forgotten by history, and I'm not here to tell history it's wrong.

"This film is a detective story--in which you are the detective."

"The question is not 'Who is the murderer?"--But 'Who is the werewolf?'"

"After all the clues have been shown--You will get a chance to give your answer."

And so we will be, as a giant stopwatch graphic hovers over the faces of the five remaining suspects (out of eight - two are dead, one has clearly been disqualified) in one of the downright goofiest whodunnits I have ever watched. To be clear, I have no objections to cross-breeding a werewolf movie and a murder mystery. It makes a kind of sense, even, as anyone who's ever played the party game Werewolf knows good and well. I don't even object to the Werewolf Break, which has an endearing kitschy quality, though I confess to being baffled by what the hook was supposed to be. Does everybody just start screaming their pick out loud in the theater? Did ushers come and take your vote? Was it a contest? Because if it was what it looks like, and it's just giving you the opportunity to quietly, in the privacy of your own brain, decide who you think the killer is, I'm pretty sure murder mysteries had already been doing that for decades by 1974, without needing to jam on the brakes right before the climax of the movie. This is, in fact, part of the reason we watch mysteries. But I suppose it's also possible that Subotsky was just mad at the movie, and wanted to punish it.

That would not be an inexplicable response. The Beast Must Die is, I regret to say, a pretty bad movie; it has terrible elements and mediocre elements, but not really any strong elements, unless you share my conviction that Peter Cushing doing literally anything whatsoever is good cinema. And if you share that conviction, The Beast Must Die is a pretty good way to test your faith, because he's really not up to anything here that he should be proud of.

The Beast Must Die tells us early how little we should expect, following up that playfully corny opening narration with a one-two punch of some hideous helicopter shots in all the flavors of grainy brown that mid-'70s film stock could muster up, accompanied by a score by Douglas Gamley that listlessly pipes in what I guess qualifies as "funk" by the standards of Great Britain in 1974. We move in close to the grounds of some sprawling estate, where a man in form-fitting black gear is stalking through the woods, apparently on the run from security forces operated by a different man in a room full of monitors. There's a horribly dispiriting "bargain basement spy thriller" vibe to all of it, with the music doing not a goddamn thing to make any of it better, but at least this turns out to be a fake-out: the man in black is Tom Newcliffe (Calvin Lockhart), the owner of the place, and he and his right-hand man Pavel (Anton Diffring) have been running tests on the security perimeter, readying for the event Tom is about to throw. This is a werewolf-hunting murder mystery party, we learn after a long amount of peek-a-boo writing that makes us wait for even the slowest of the characters to catch up before confirming that the film with a "Werewolf Break" has a werewolf in it. Tom is, among his many rich person hobbies, a big game hunter, and werewolves are the last frontier of big game; he has a lead on a possible lycanthrope, and has gathered the likeliest suspects to spend some time with he and his wife Caroline (Marlene Clark), who clearly thinks this whole thing is disgusting madness, and is plainly starting to re-evaluate how much her current lifestyle justifies being married to this insane person.

The guests/suspects are Arthur Bennington (Charles Gray), a former diplomat, now disgraced; Jan Gilmore (Michael Gambon), a surly pianist, and his wife Davina (Ciaran Madden); convicted cannibal Paul Foote (Tom Chabon), who declares with a kind of smirk that it was basically part of a med school prank, but doesn't deny it; and Dr. Christopher Lundgren (Cushing), a mild-mannered archaeologist who is one of the country's foremost amateur werewolf experts. For nearly all of the film's desperately slow-moving 92-minute film, we will watch Tom sit these people down and yell at them in various parlors, all of them shot with ugly flatness by Annett (a TV director making his first feature, and you can tell) and cinematographer Jack Hildyard (who had worked with David Lean and Alfred Hitchcock, and you can't tell), providing virtually no actual evidence for the audience to begin chewing over, in part because nothing has actually happened about which we can form an opinion one way or another. Eventually, we see the werewolf in action, and the very happy German Shepherd playing the murderous beast is, at least, more charismatic than any of the people who might have transformed into it.

The lack of active content, mixed together with the extremely cumbersome way that screenwriter Michael Winder (adapting a story by James Blish) handles the unnecessarily complicated exposition, would be all that it takes to make sure that The Beast Must Die would suck all the fun out of its hokey premise; the decayed brown palette muddying things up visually and the scattershot pacing (sometimes much too fast, as in the pre-guest exposition phase; more often much too slow, as when we stop on go-nowhere conversations that feel like they take up an entire reel) muddying things up narratively are just there for redundancy's sake. But despite all of that, I think I hate the acting worst, and not just because the film has forced me into a horrible confrontation with the reality that Cushing can be boring in a film, so committed to the clipped, mannered pattern of speech he's adopted for his character that he forgets to do anything but robotically puke out werewolf lore. He's still closer to being the best actor in the cast than the worst: the worst is obviously Lockhart, which is too bad given that he's also in the movie by far the most often. His performance is a deadly form of overly-enunciated hamminess, like something out of children's theater, making every bit of slack dialogue come across with florid, breathless urgency and gesturing with pantomime-like ferocity. It's weird and ineffectiveness to be curiously engaging, which I guess is more than anyone else can claim, but it's tiring. Meanwhile, Gray, Gambon, and Clark snooze their way through, Madden has a wild, deer-in-the-headlights star, and Chadbon is alone able to make something like a character out of this, largely because his snotty smartass with a shit-eating grin is the only person in the movie who gets to have any fun. Which seems like something more people in a werewolf murder mystery ought to be doing.

That lack of fun is pretty much the film's whole thing: it has neither real atmosphere nor energetic kitschiness, and it just kind of drags itself out, punishing us for having an interest in it. The weird novelty of the plot is different, at least, but mostly this feels like the worst of all worlds: too square for '70s horror, too glum and realist for a campy throwback. It's a bleak finale for the storied run of Amicus Productions horror films - this was the last of those movies produced by the studio, and the second-to-last released, and the only one that remained - Madhouse, from the same summer of '74 - was more of an American International Pictures production that Amicus happened to help out with. Still, it's pleasurable to consider that film to be the true Amicus finale; The Beast Must Die is a dull sack of crap that has been almost entirely forgotten by history, and I'm not here to tell history it's wrong.