To absent friends

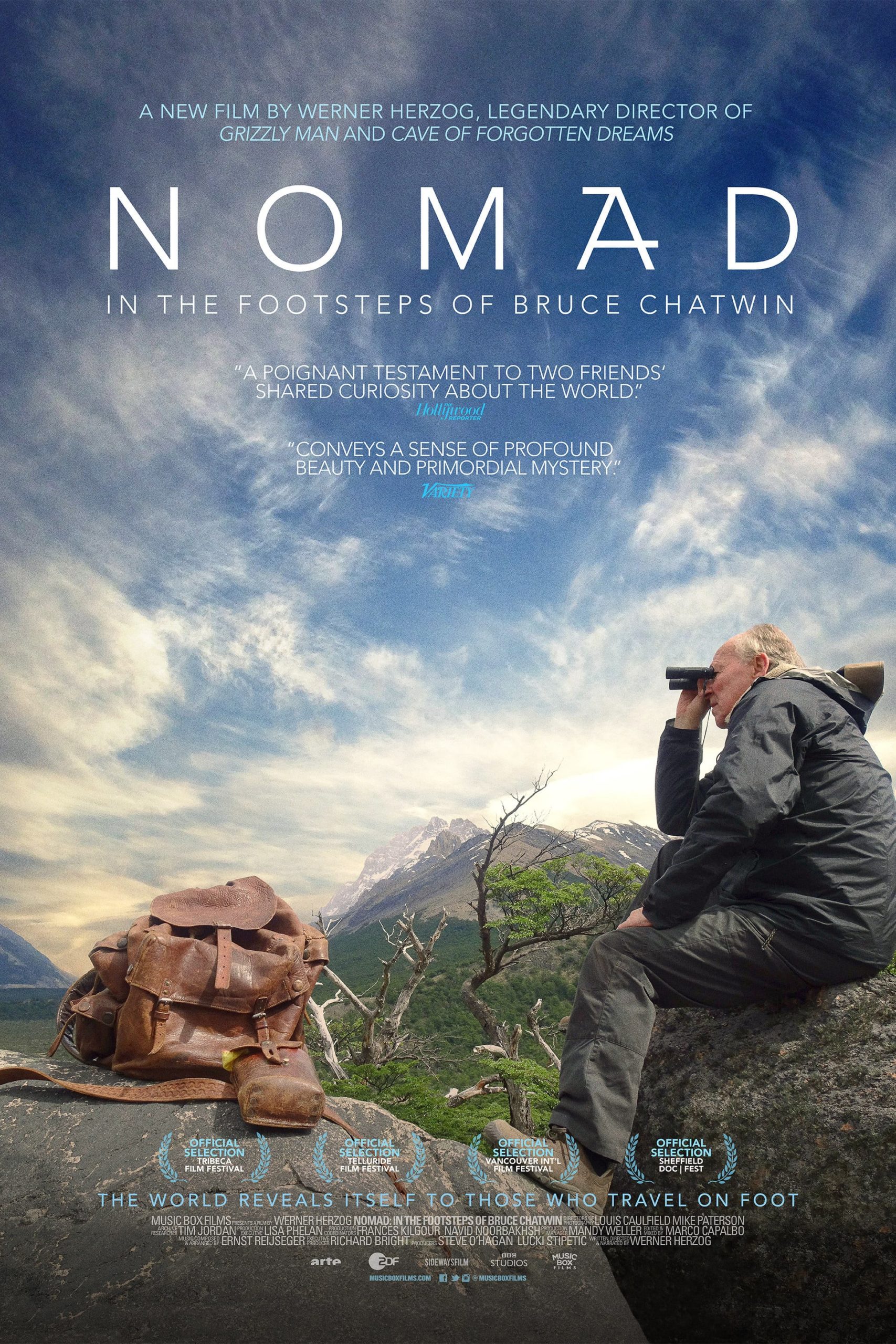

It's hard to imagine a more profoundly unsentimental film director - or person - than Werner Herzog. Good ol' Werner "The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don't think they sing. They just screech in pain" Herzog. Or Werner "Life on our planet has been a constant series of cataclysmic events, and we are more suitable for extinction than a trilobite or a reptile" Herzog. Or Werner "I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility, and murder" Herzog. Or Werner "Look into the eyes of a chicken and you will see real stupidity. It is a kind of bottomless stupidity, a fiendish stupidity. They are the most horrifying, cannibalistic and nightmarish creatures in the world". You know, that cheerful guy. And yet, with the 2019 documentary Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, we see an unabashedly sweet-natured, generous, loving side of Herzog that I guess could have been predicted to exist in some format (he is a human being, after all), though I would never have expected it to emerge in the form of such a tender, giving tribute to a long-dead friend.

That being Bruce Chatwin, the celebrated British travelogue writer, who died in January, 1989; this film was commissioned by the BBC in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of his passing. He and Herzog had crossed paths several times, and Herzog's 1987 film Cobra Verde was adapted from Chatwin's 1980 novel The Viceroy of Ouidah. As the director tells it, he was one of the last people to visit Chatwin before the writer's death, and his recollection of his final memories of Chatwin, saved till near the end of the film, offer the previously unimaginable spectacle of Werner Herzog being overcome with sentimental sadness.

Nomad is not, however, a story of Chatwin and Herzog's friendship, nor a biography of Chatwin, though both of those things keep showing up on the edges. Rather, the film is (as its subtitle promises) an attempt to capture something of Chatwin's freewheeling journeys through the world, meditating on his reactions to what he saw and meditating as well on the fact that, thirty years after he died and forty years or more after he witnessed the things he wrote about, Herzog was able to witness those same things, and thus find a kind of mental communion with the author. It's a travelogue about a travelogue, in effect - "in the footsteps of Bruce Chatwin", just like it says.

This ends up giving the film a remarkably fresh identity. At a first approximation, this is basically just more of the same stuff Herzog has been giving us for years, particularly in his late turn towards travel documentaries: go to different places in the world that would not appear to have anything obvious connecting them, chatting with whomever he finds there, and learning about the way they inhabit the world and what fascinates them, and then finding some that he, at least, believes to be the underlying commonality between all of it. This has been at times enormously productive, at times not, but by the time of 2016's Into the Inferno, it had certainly started to stiffen, and it's quite a pleasure to be able to report that Nomad has brought some flexibility back to the formula. The reason for this is obvious enough: Herzog is challenging himself to view the world through Chatwin's eyes, or what he considers Chatwin's eyes would have seen. This sometimes takes an extremely literal form: at one point in the first of the film's eight chapters, visiting the sites of Chatwin's career-making 1977 In Patagonia, Herzog films a slowly-decaying wreck of a ship from the same angle that Chatwin had photographed it more than forty years prior, finding that it looks almost exactly the same. It's a quietly heart-stopping moment, erasing not just the time between Chatwin and Herzog but between either of them and the moment of the wreck, capturing a tiny feeling of eternity for a few moments of footage.

This ends up being the secret of Nomad: it creates a feeling of awe. Not that Herzog hasn't been able to create his own feeling of awe, of course; he has decades of films full of some of the most astonishing imagery that a director has ever wrangled into being, and he frequently treats it with the reverence due to some of the most unusual sights the planet can offer. But there's something clinical about his relationship to these images, an attempt to articulate his way around his footage in the clipped precision of his legendary Bavarian accent. In Nomad, he allows for a sense of pure dazzling beauty to emerge from the footage, resisting the urge to clamp it down into an intellectual system, and I have to assume this is his way of trying to honor Chatwin's relationship to these sights and places. It's the difference between "awesome = terrifying" and "awesome = amazing", is perhaps the simplest way to explain the difference between Nomad and Herzog's other films of this sort, and the fresh, vital joy in the beauty of the images, places, and people that comes from this shift in attitude is tremendous. It is curious and celebratory in an untroubled way.

There are limits to this approach, which restrains itself from fully interrogating anything; there is a certain tendency to take Chatwin at face value, which can be admirable in some ways (Herzog blunty refuses to indulge in gossipy chatter about Chatwin's bisexuality), but does leave mostly unaddressed the criticisms, persistent throughout the author's life, that he was a fabulist, or at least a serial exaggerator, and given to exoticising the indigenous cultures he crossed paths with. Insofar as Nomad touches on this at all, it's to vaguely imply that Chatwin's embellishments were a kind of "Truth Plus", and it's not all that surprising that the filmmakers whose documentaries have for so many years blurred the distinction between "facts" and "made-up bullshit", and who has articulated an idea of "ecstatic truth" as the correct domain of documentary filmmaking, rather than mere journalism, would simply not care whether Chatwin was, in a technical sense, making things up. Still, it feels like a conscious omission.

The film also ends up feeling a bit stretched-out, even at a tidy 89 minutes; the eight chapters all cover distinct material, but it does end up being the case that Chatwin's interests in different parts of the world that the things we can say about his time in Australia are rather like the things we can about his time in South America, or even Wales. And so, towards the end, it becomes clear that we're hearing things we already heard, and no matter ho much animation Herzog puts into his recollections about Chatwin (this is a film full of two-sided conversations between the director and other friends and acquaintances of Chatwin, and he structures his memories in terms of the films he was working on at the time of this or that interaction with his fellow traveler), there's no getting around how much they start to feel familiar. Which is maybe part of the appeal; the film is trying for a kind of intimacy-by-proxy, and part of what knowing someone very well means is that they cease to surprise you, so much. Still, in the context of an hour-and-a-half movie, redundancy is redundancy. Regardless, the film's obvious affection of its subject, and its overwhelmingly earnest emotional appeals, make it quite a nice, lovely time spent in the company of interesting thoughts offered by interesting. It's the most energetic, inquisitive film by Herzog in years, since 2011's Into the Abyss, I'd say, and one of the kindest things he's ever made, even if it doesn't have the intellectual stamina to make it into the top tier of his filmography.

That being Bruce Chatwin, the celebrated British travelogue writer, who died in January, 1989; this film was commissioned by the BBC in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of his passing. He and Herzog had crossed paths several times, and Herzog's 1987 film Cobra Verde was adapted from Chatwin's 1980 novel The Viceroy of Ouidah. As the director tells it, he was one of the last people to visit Chatwin before the writer's death, and his recollection of his final memories of Chatwin, saved till near the end of the film, offer the previously unimaginable spectacle of Werner Herzog being overcome with sentimental sadness.

Nomad is not, however, a story of Chatwin and Herzog's friendship, nor a biography of Chatwin, though both of those things keep showing up on the edges. Rather, the film is (as its subtitle promises) an attempt to capture something of Chatwin's freewheeling journeys through the world, meditating on his reactions to what he saw and meditating as well on the fact that, thirty years after he died and forty years or more after he witnessed the things he wrote about, Herzog was able to witness those same things, and thus find a kind of mental communion with the author. It's a travelogue about a travelogue, in effect - "in the footsteps of Bruce Chatwin", just like it says.

This ends up giving the film a remarkably fresh identity. At a first approximation, this is basically just more of the same stuff Herzog has been giving us for years, particularly in his late turn towards travel documentaries: go to different places in the world that would not appear to have anything obvious connecting them, chatting with whomever he finds there, and learning about the way they inhabit the world and what fascinates them, and then finding some that he, at least, believes to be the underlying commonality between all of it. This has been at times enormously productive, at times not, but by the time of 2016's Into the Inferno, it had certainly started to stiffen, and it's quite a pleasure to be able to report that Nomad has brought some flexibility back to the formula. The reason for this is obvious enough: Herzog is challenging himself to view the world through Chatwin's eyes, or what he considers Chatwin's eyes would have seen. This sometimes takes an extremely literal form: at one point in the first of the film's eight chapters, visiting the sites of Chatwin's career-making 1977 In Patagonia, Herzog films a slowly-decaying wreck of a ship from the same angle that Chatwin had photographed it more than forty years prior, finding that it looks almost exactly the same. It's a quietly heart-stopping moment, erasing not just the time between Chatwin and Herzog but between either of them and the moment of the wreck, capturing a tiny feeling of eternity for a few moments of footage.

This ends up being the secret of Nomad: it creates a feeling of awe. Not that Herzog hasn't been able to create his own feeling of awe, of course; he has decades of films full of some of the most astonishing imagery that a director has ever wrangled into being, and he frequently treats it with the reverence due to some of the most unusual sights the planet can offer. But there's something clinical about his relationship to these images, an attempt to articulate his way around his footage in the clipped precision of his legendary Bavarian accent. In Nomad, he allows for a sense of pure dazzling beauty to emerge from the footage, resisting the urge to clamp it down into an intellectual system, and I have to assume this is his way of trying to honor Chatwin's relationship to these sights and places. It's the difference between "awesome = terrifying" and "awesome = amazing", is perhaps the simplest way to explain the difference between Nomad and Herzog's other films of this sort, and the fresh, vital joy in the beauty of the images, places, and people that comes from this shift in attitude is tremendous. It is curious and celebratory in an untroubled way.

There are limits to this approach, which restrains itself from fully interrogating anything; there is a certain tendency to take Chatwin at face value, which can be admirable in some ways (Herzog blunty refuses to indulge in gossipy chatter about Chatwin's bisexuality), but does leave mostly unaddressed the criticisms, persistent throughout the author's life, that he was a fabulist, or at least a serial exaggerator, and given to exoticising the indigenous cultures he crossed paths with. Insofar as Nomad touches on this at all, it's to vaguely imply that Chatwin's embellishments were a kind of "Truth Plus", and it's not all that surprising that the filmmakers whose documentaries have for so many years blurred the distinction between "facts" and "made-up bullshit", and who has articulated an idea of "ecstatic truth" as the correct domain of documentary filmmaking, rather than mere journalism, would simply not care whether Chatwin was, in a technical sense, making things up. Still, it feels like a conscious omission.

The film also ends up feeling a bit stretched-out, even at a tidy 89 minutes; the eight chapters all cover distinct material, but it does end up being the case that Chatwin's interests in different parts of the world that the things we can say about his time in Australia are rather like the things we can about his time in South America, or even Wales. And so, towards the end, it becomes clear that we're hearing things we already heard, and no matter ho much animation Herzog puts into his recollections about Chatwin (this is a film full of two-sided conversations between the director and other friends and acquaintances of Chatwin, and he structures his memories in terms of the films he was working on at the time of this or that interaction with his fellow traveler), there's no getting around how much they start to feel familiar. Which is maybe part of the appeal; the film is trying for a kind of intimacy-by-proxy, and part of what knowing someone very well means is that they cease to surprise you, so much. Still, in the context of an hour-and-a-half movie, redundancy is redundancy. Regardless, the film's obvious affection of its subject, and its overwhelmingly earnest emotional appeals, make it quite a nice, lovely time spent in the company of interesting thoughts offered by interesting. It's the most energetic, inquisitive film by Herzog in years, since 2011's Into the Abyss, I'd say, and one of the kindest things he's ever made, even if it doesn't have the intellectual stamina to make it into the top tier of his filmography.

Categories: documentaries, travelogues, werner herzog