Amicus Horror: The Price of fame

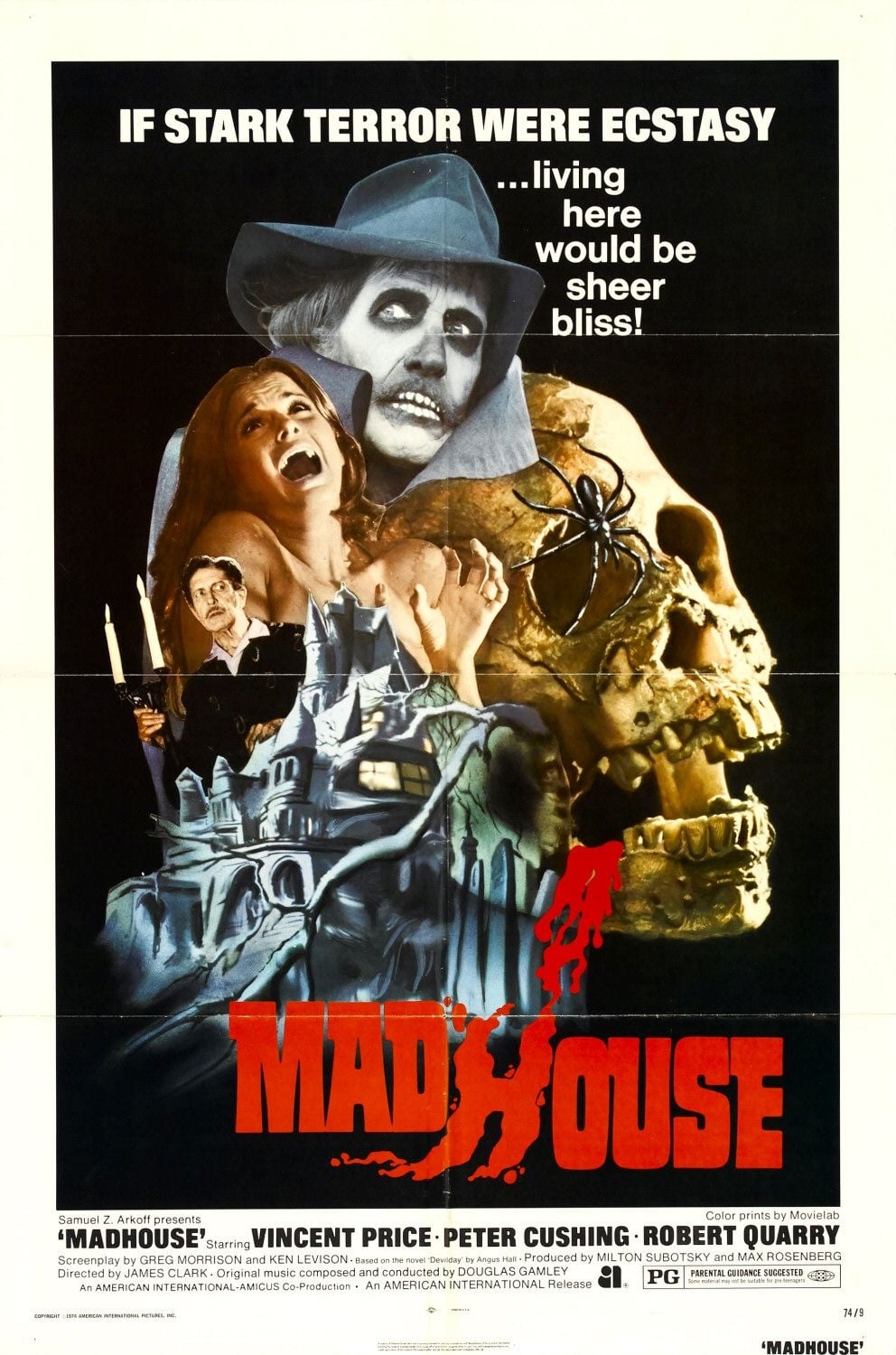

There have been horror movie icons since the 1920s, and naturally enough, every one of them has to have their Very Last Horror Movie. But not a one of them had a grand finale to their time as a star of horror movies like Vincent Price, who was shipped out of the genre in grand fashion with 1974's Madhouse.

This is oversimplifying things, of course. Price's career lasted another 18 years after Madhouse, and during that time he appeared in multiple horror films, after a fashion. Some of them were anthologies or short films. Some of them were cameos. Some of them were comedies genially poking fun at Price's horror movie image. Some of them were combinations of the above. So what I'm really saying is that Madhouse is the last time Price had the leading role in a feature-length horror film that was taking itself seriously. Which is of course qualifying things quite a bit.

Still, one wants to make some kind of claim for Madhouse, which has the unmistakable feel of a valediction, not just for Price's career as a horror movie leading man, but for an entire ethos of horror movie-making. And this is something nobody else got: not Boris Karloff (whose last film was The Incredible Invasion, one of a handful of posthumous cheapies he shot for a Mexican company shortly before his death); not Lon Chaney, Jr. (whose last film was Dracula vs. Frankenstein, a dismal bit of nonsense by Al Adamson); damn sure not Béla Lugosi (whose last film was, infamously, Plan 9 from Outer Space). So I say let's fudge things a little bit, because Madhouse is exactly what you'd want for a living legend to receive as a going-away present: worshipfully aware of his career and what it has meant, but still interested in his skills and what he can bring to the project, rather than treating him as a beneficent saint. And Price knew this, I think. You can always tell when he believed that there was real meat in a screenplay: he dials back the campiness and overacting for which he is best known and works on drawing out the character as a psychological actor rather than a collection of garish poses. And by the standards of a Vincent Price movie from 1974 with a splashy series of murders perpetrated by a person in a living skeleton costume, Madhouse is almost alarmingly free of camp.

Having thus built it up so much, I should embarrass myself by making it clear sooner rather than later: I don't actually love Madhouse. This was, by my count, the sixth time Price had appeared in basically this exact same film, after House of Wax (1953), The Mad Magician (1954), The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971), Dr. Phibes Rises Again (1972), and Theatre of Blood (1973) - the fourth time in four consecutive years, in other words, and I'd say that of those four, the first Phibes and Theatre of Blood are both incontestably better than Madhouse. So are House of Wax and The Mad Magician, for that matter, though maybe with more room to contest it. The narrative mechanics are a bit stiff, with screenwriters Ken Levison and Greg Morrison (adapting a novel by Angus Hall) belaboring the story and underlining the function of every scene, and director Jim Clark has no flair for theatricality. This is a real shame, given that the film's subject is garish horror B-cinema; while I appreciate that the goal was for something more elegiac and pensive than unbridled camp of a Phibes, the filmmakers still probably could have gone a little bit more over the top than we see here, celebrating the artifice of horror filmmaking rather than just pleasantly walking us around a film set a few times.

That being said, the film's inside-out view of filmmaking and the career of a very Price-like actor named Paul Toombes (a name never really played as a joke, which is maybe a good sign of how little silliness Madhouse wants to traffic in), are among its best strengths. The film sets presented within the movie are bustling with activity, much of it buried in the background where it has no impact on the plot, and one of the few ways that Clark strives to have any distinct stylistic personality comes from the way he switches over to a restless, tracking camera for the establishing shots inside the film studio. As I said, the film is a bit of a loving farewell to an entire mode of B-movie production: the hokey old-fashioned studio-bound spook shows that American International Pictures and Amicus Productions, which co-produced the movie, had made their bread and butter (perhaps to commemorate this, the famous "house on fire" stock footage first seen in AIP's 1960 House of Usher puts in what I believe to be its final big-screen appearance). This was, indeed, the final horror film Amicus released (though it was produced a few weeks prior to The Beast Must Die), with that studio briefly attempting to keep itself alive with a one-per-year trio of Edgar Rice Burroughs adventure stories before finally folding as part of the general softening of the British film industry around the same time (Hammer Films, the ten-ton giant that had always relegated Amicus to second-class status, only managed to squeeze out two more features after 1974). AIP had a bit more life left in it, but it substantially moved away from horror for the rest of the half-decade it still existed, and when it did drop into the genre, it was generally in the more naturalistic, grungy form that horror production started to take in the 1970s, as it embraced the traits of low-budget exploitation more and more. Madhouse was already a faintly musty throwback by the time it came out, but it's never pretending otherwise: being out of step with the present is very much the point, and even part of the story.

That story, for the record, is that Paul, several years after having a nervous breakdown and spending most of the time in a mental institution (the closest the film ever comes to having an actual madhouse) has been approached to start working again. So far, so good, except that the nervous breakdown, as we saw in the opening scene set at a swinging Hollywood party, presumably in the early '50s, was caused by the decapitation of his fiancé Ellen (Julie Crosthwaite) the very night that they announced their engagement - the very same night that a snotty skin-flick producer named Oliver Quayle (Robert Quarry) took great pleasure in letting Paul know that Julie had logged some time in his movies before being getting the gig as his co-star in his most recent production. Worse yet, the killer was dressed as Paul's character from that film, a skeletal madman in a cloak named Dr. Death. Worst of all, Paul was in a bit of a drunken fugue state after hearing the news about his future wife's history in nudie pictures, and he's no more sure than the hostile industry that he's not guilty of the crime. So he's extremely reluctant when his old screenwriting buddy Herbert Flay (Peter Cushing), author of all five Dr. Death pictures, calls him up to say that they've been given an offer to resurrect the character in a British television series. Despite his instantaneous sense of dread, Paul agrees, mostly to help his dear friend out, and is horrified to find that the show is being produced by that very same Oliver Quayle. And of course, in this hothouse of potential psychopaths, it's not at all a shock when people connected to Paul - usually to his annoyance - end up dead in re-creations of setpieces from the Dr. Death movies.

The pleasure here does not lie in the mystery, which frankly doesn't have much gas: given the way the film starts unfolding and the way it marshals its cast members, it's almost immediately clear that Price, Cushing, or Quarry has to be playing the killer, especially once the latter two disappear from the movie for long stretches. And this never once feels like the kind of movie to actually play the "I didn't realise I was killing people during my blackouts" card, which takes Paul out of the running, so we're down to a 50-50 shot almost as soon as there's even a mystery to solve. The pleasure also doesn't lie in the murders, which are mostly done chastely, off-camera, and without to flair for the baroque that made the two Phibes films and Theatre of Blood so colorful. The pleasure is almost entirely in seeing an entire motion picture bend itself around the notion that Vincent Price's career as a hammy, kitschy madman has been such a constant source of joy over the preceding 21 years that the least we can do is build an entire film around celebrating it. That's really what the story is about what happens when an actor of Price's uncommon mixture of indefatigably dignity and ripe silliness walks in front of a camera and gets to pour himself into the florid dialogue and trashy situations of low-budget horror.

Price himself is exceptionally good. I have mentioned my belief that he's is trying unusually hard here to be sober and grounded in building his character, and he's largely succeeding: Paul isn't a figure of Shakespearean depth and layering, but the trembling self-doubt of a man who really can't tell if he's butchering people left and right gives Price something that could be played in at least a few different ways, and he doesn't pick the obvious ones (that is to say: Price isn't playing Paul as a florid madman, but he does play the nervous "don't pay attention to me" paranoia of a man who is worried somebody will catch him out on the secret he may or may not possess). Beyond that, Price is also pretty fantastic at playing a funhouse mirror version of himself: an actor whose strength lied in grand melodramatic gestures, effortless personal charisma, and a good sense of humor, who is now miserable and bereft of self-confidence - he's playing Paul as Sad Price, in effect, what happens when that charisma and humor and wonderfully kitschy affect have been stripped bare through a kind of ego death. There's something very tender and sweet about it, not two adjectives that one would necessarily anticipate from a film where a skull-faced man in a hood named Dr. Death is murdering people.

The film really does put everything it has on our loving Price, and loving him in this role: I would be hard-pressed to name any other facet of its production, other than maybe Douglas Gamley's tongue-in-cheek score, full of bombastic horror clichés. No other actor registers much at all; Cushing has a very lovely open enthusiasm in his scenes with Price, playing an upbeat, endlessly cheerful friend trying to make the best of a shitty life, but he's simply not in that much of the movie, and nothing about the performance seems especially taxing. If the film has any genuinely creative idea at all, it's to pull in a great deal of footage from Price's earlier films, mostly the AIP Poe cycle directed by Roger Corman, suggesting rather dubiously that it's from Paul's Dr. Death movies (I can buy this up to a point, but certainly not the bits we see from Tales of Terror, in which Price is a helpless victim of hypnosis. The footage did allow the filmmakers a shamelessly inappropriate "special appearance by Basil Rathbone" credit, so good for them, I guess. Boris Karloff makes a similar posthumous "special appearance"). Which is to say, it's a creative idea, but the execution is largely perfunctory, and there's a strong sense in which the purpose is less to contextualise Paul's story than to throw some Price treats to all of us hungry fans in the audience.

A fun and rewarding way to mark all of those various finales, then, but not an especially high mark for either Amicus or AIP, and despite how much more he seems to be putting of himself into the project, I can't call this one of my favorite Price performances, either. Still, if it's a hard movie to like, it's extremely easy to love: it's a cheesy movie about how gosh-darn great cheesy movies are, and, well, that's just the truth. Not a deep truth, maybe, but they don't all get to be deep.

This is oversimplifying things, of course. Price's career lasted another 18 years after Madhouse, and during that time he appeared in multiple horror films, after a fashion. Some of them were anthologies or short films. Some of them were cameos. Some of them were comedies genially poking fun at Price's horror movie image. Some of them were combinations of the above. So what I'm really saying is that Madhouse is the last time Price had the leading role in a feature-length horror film that was taking itself seriously. Which is of course qualifying things quite a bit.

Still, one wants to make some kind of claim for Madhouse, which has the unmistakable feel of a valediction, not just for Price's career as a horror movie leading man, but for an entire ethos of horror movie-making. And this is something nobody else got: not Boris Karloff (whose last film was The Incredible Invasion, one of a handful of posthumous cheapies he shot for a Mexican company shortly before his death); not Lon Chaney, Jr. (whose last film was Dracula vs. Frankenstein, a dismal bit of nonsense by Al Adamson); damn sure not Béla Lugosi (whose last film was, infamously, Plan 9 from Outer Space). So I say let's fudge things a little bit, because Madhouse is exactly what you'd want for a living legend to receive as a going-away present: worshipfully aware of his career and what it has meant, but still interested in his skills and what he can bring to the project, rather than treating him as a beneficent saint. And Price knew this, I think. You can always tell when he believed that there was real meat in a screenplay: he dials back the campiness and overacting for which he is best known and works on drawing out the character as a psychological actor rather than a collection of garish poses. And by the standards of a Vincent Price movie from 1974 with a splashy series of murders perpetrated by a person in a living skeleton costume, Madhouse is almost alarmingly free of camp.

Having thus built it up so much, I should embarrass myself by making it clear sooner rather than later: I don't actually love Madhouse. This was, by my count, the sixth time Price had appeared in basically this exact same film, after House of Wax (1953), The Mad Magician (1954), The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971), Dr. Phibes Rises Again (1972), and Theatre of Blood (1973) - the fourth time in four consecutive years, in other words, and I'd say that of those four, the first Phibes and Theatre of Blood are both incontestably better than Madhouse. So are House of Wax and The Mad Magician, for that matter, though maybe with more room to contest it. The narrative mechanics are a bit stiff, with screenwriters Ken Levison and Greg Morrison (adapting a novel by Angus Hall) belaboring the story and underlining the function of every scene, and director Jim Clark has no flair for theatricality. This is a real shame, given that the film's subject is garish horror B-cinema; while I appreciate that the goal was for something more elegiac and pensive than unbridled camp of a Phibes, the filmmakers still probably could have gone a little bit more over the top than we see here, celebrating the artifice of horror filmmaking rather than just pleasantly walking us around a film set a few times.

That being said, the film's inside-out view of filmmaking and the career of a very Price-like actor named Paul Toombes (a name never really played as a joke, which is maybe a good sign of how little silliness Madhouse wants to traffic in), are among its best strengths. The film sets presented within the movie are bustling with activity, much of it buried in the background where it has no impact on the plot, and one of the few ways that Clark strives to have any distinct stylistic personality comes from the way he switches over to a restless, tracking camera for the establishing shots inside the film studio. As I said, the film is a bit of a loving farewell to an entire mode of B-movie production: the hokey old-fashioned studio-bound spook shows that American International Pictures and Amicus Productions, which co-produced the movie, had made their bread and butter (perhaps to commemorate this, the famous "house on fire" stock footage first seen in AIP's 1960 House of Usher puts in what I believe to be its final big-screen appearance). This was, indeed, the final horror film Amicus released (though it was produced a few weeks prior to The Beast Must Die), with that studio briefly attempting to keep itself alive with a one-per-year trio of Edgar Rice Burroughs adventure stories before finally folding as part of the general softening of the British film industry around the same time (Hammer Films, the ten-ton giant that had always relegated Amicus to second-class status, only managed to squeeze out two more features after 1974). AIP had a bit more life left in it, but it substantially moved away from horror for the rest of the half-decade it still existed, and when it did drop into the genre, it was generally in the more naturalistic, grungy form that horror production started to take in the 1970s, as it embraced the traits of low-budget exploitation more and more. Madhouse was already a faintly musty throwback by the time it came out, but it's never pretending otherwise: being out of step with the present is very much the point, and even part of the story.

That story, for the record, is that Paul, several years after having a nervous breakdown and spending most of the time in a mental institution (the closest the film ever comes to having an actual madhouse) has been approached to start working again. So far, so good, except that the nervous breakdown, as we saw in the opening scene set at a swinging Hollywood party, presumably in the early '50s, was caused by the decapitation of his fiancé Ellen (Julie Crosthwaite) the very night that they announced their engagement - the very same night that a snotty skin-flick producer named Oliver Quayle (Robert Quarry) took great pleasure in letting Paul know that Julie had logged some time in his movies before being getting the gig as his co-star in his most recent production. Worse yet, the killer was dressed as Paul's character from that film, a skeletal madman in a cloak named Dr. Death. Worst of all, Paul was in a bit of a drunken fugue state after hearing the news about his future wife's history in nudie pictures, and he's no more sure than the hostile industry that he's not guilty of the crime. So he's extremely reluctant when his old screenwriting buddy Herbert Flay (Peter Cushing), author of all five Dr. Death pictures, calls him up to say that they've been given an offer to resurrect the character in a British television series. Despite his instantaneous sense of dread, Paul agrees, mostly to help his dear friend out, and is horrified to find that the show is being produced by that very same Oliver Quayle. And of course, in this hothouse of potential psychopaths, it's not at all a shock when people connected to Paul - usually to his annoyance - end up dead in re-creations of setpieces from the Dr. Death movies.

The pleasure here does not lie in the mystery, which frankly doesn't have much gas: given the way the film starts unfolding and the way it marshals its cast members, it's almost immediately clear that Price, Cushing, or Quarry has to be playing the killer, especially once the latter two disappear from the movie for long stretches. And this never once feels like the kind of movie to actually play the "I didn't realise I was killing people during my blackouts" card, which takes Paul out of the running, so we're down to a 50-50 shot almost as soon as there's even a mystery to solve. The pleasure also doesn't lie in the murders, which are mostly done chastely, off-camera, and without to flair for the baroque that made the two Phibes films and Theatre of Blood so colorful. The pleasure is almost entirely in seeing an entire motion picture bend itself around the notion that Vincent Price's career as a hammy, kitschy madman has been such a constant source of joy over the preceding 21 years that the least we can do is build an entire film around celebrating it. That's really what the story is about what happens when an actor of Price's uncommon mixture of indefatigably dignity and ripe silliness walks in front of a camera and gets to pour himself into the florid dialogue and trashy situations of low-budget horror.

Price himself is exceptionally good. I have mentioned my belief that he's is trying unusually hard here to be sober and grounded in building his character, and he's largely succeeding: Paul isn't a figure of Shakespearean depth and layering, but the trembling self-doubt of a man who really can't tell if he's butchering people left and right gives Price something that could be played in at least a few different ways, and he doesn't pick the obvious ones (that is to say: Price isn't playing Paul as a florid madman, but he does play the nervous "don't pay attention to me" paranoia of a man who is worried somebody will catch him out on the secret he may or may not possess). Beyond that, Price is also pretty fantastic at playing a funhouse mirror version of himself: an actor whose strength lied in grand melodramatic gestures, effortless personal charisma, and a good sense of humor, who is now miserable and bereft of self-confidence - he's playing Paul as Sad Price, in effect, what happens when that charisma and humor and wonderfully kitschy affect have been stripped bare through a kind of ego death. There's something very tender and sweet about it, not two adjectives that one would necessarily anticipate from a film where a skull-faced man in a hood named Dr. Death is murdering people.

The film really does put everything it has on our loving Price, and loving him in this role: I would be hard-pressed to name any other facet of its production, other than maybe Douglas Gamley's tongue-in-cheek score, full of bombastic horror clichés. No other actor registers much at all; Cushing has a very lovely open enthusiasm in his scenes with Price, playing an upbeat, endlessly cheerful friend trying to make the best of a shitty life, but he's simply not in that much of the movie, and nothing about the performance seems especially taxing. If the film has any genuinely creative idea at all, it's to pull in a great deal of footage from Price's earlier films, mostly the AIP Poe cycle directed by Roger Corman, suggesting rather dubiously that it's from Paul's Dr. Death movies (I can buy this up to a point, but certainly not the bits we see from Tales of Terror, in which Price is a helpless victim of hypnosis. The footage did allow the filmmakers a shamelessly inappropriate "special appearance by Basil Rathbone" credit, so good for them, I guess. Boris Karloff makes a similar posthumous "special appearance"). Which is to say, it's a creative idea, but the execution is largely perfunctory, and there's a strong sense in which the purpose is less to contextualise Paul's story than to throw some Price treats to all of us hungry fans in the audience.

A fun and rewarding way to mark all of those various finales, then, but not an especially high mark for either Amicus or AIP, and despite how much more he seems to be putting of himself into the project, I can't call this one of my favorite Price performances, either. Still, if it's a hard movie to like, it's extremely easy to love: it's a cheesy movie about how gosh-darn great cheesy movies are, and, well, that's just the truth. Not a deep truth, maybe, but they don't all get to be deep.