Practice what you preach

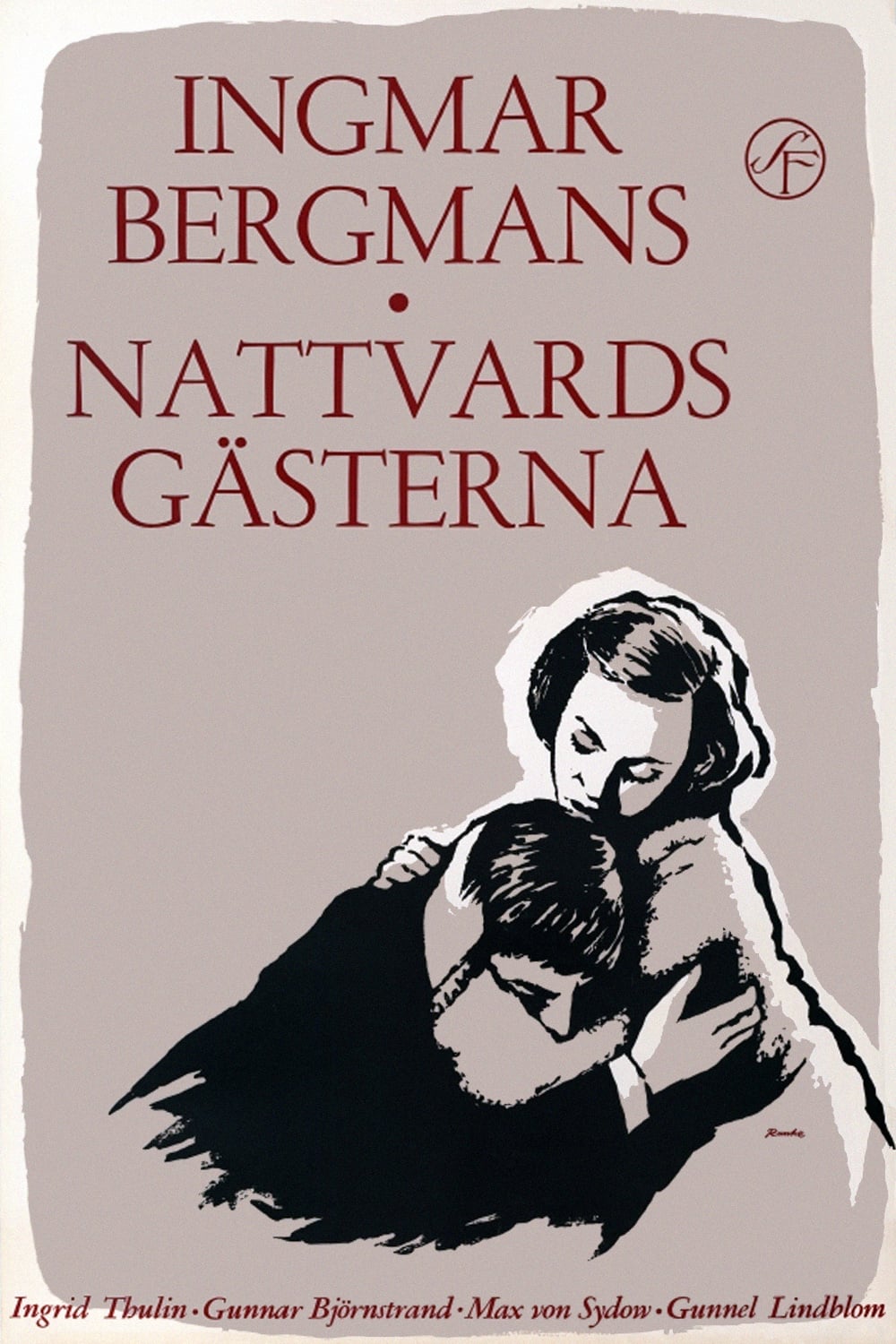

When I think upon Ingmar Bergman's cinema, and what most perfectly embodies it, why he is one of my very favorite filmmakers of all time and what are the irreducible components of his style, what I always think of first is Winter Light from 1963. Specifically, I think of the shot of Ingrid Thulin's face. There are, to be sure, many shots of Thulin's face in the film - there are many shots of multiple actors' faces in the film, and every single one of them is a perfect shot. For when it comes down to it, I think that it's a perfect film, and we'll spend some time going over why.

In the meantime, though, I was talking about the shot of Thulin's face, and if you've seen Winter Light, then you know why I feel so free and easy using the definite article. Because while there are many shots of her face in the movie, there's only one that's The Shot, or at least only two, given that The Shot is briefly interrupted by a cutaway, and I have no reason not to assume that we're seeing two different takes. The shot is a medium close-up, with Thulin framed exactly in the middle, staring directly into the lens, and she delivers a monologue in two merciless long takes - the first is about four and a half minutes long, the second about two minutes long. I think it is one of the pinnacles of sound cinema. The human face is, after all, one of the great cinematic subjects, and Bergman was, at this time, entering the phase of his career where he became quite possibly the greatest director of faces the medium had ever known. Visually, Winter Light is something of an exercise in the use of faces. There's the matter of how they go into editing rhythms: who are we looking at, what are they looking at, what do they think while they're looking at it, and all of that modulated by each line of dialogue and each shift in the dynamic between characters. And there is the matter of how they are positioned in the frame, and how that affects the psychologically expressive power that is the reason for close-ups and medium close-ups in the first place.

It's not necessarily the case that any of this is radical or transformative, for the most part; only that it is done extraordinarily well. Winter Light is generally described as being a film about living in a universe where God, if He exists, refuses to say anything to us, and that's definitely inside of it. But it is also, I think more importantly, about the pain of the characters coming to that realisation. That is to say: it's a character drama, not a philosophical tract, and this is something that I think people sometimes lose track of with Bergman films starting around this point. He is certainly a film artist playing around with The Big Ideas, but he's also someone whose films are always about characters who have been imbued with deep feeling and inner lives by incredibly gifted actors working at an eerily confident level with their director. We are always invited to watch first for the human story, second for the heavy, grandiose themes, and that's true even the themes are at their most crushing, as they are in Winter Light.

This is to say: yes, Winter Light is about God's silence. But really, it's about how his horrifying awareness of God's silence affects Pastor Tomas Ericsson (Gunnar Björnstrand), who preaches in a small town in central Sweden. Tomas has, for some time we can imagine, been going through the motions, having long since come to suspect that there is no plan, no divine guidance, no Godlike love; you could call him a doubting Tomas. And that's only half of what makes this the most groaning, political-cartoon-level symbolic name in all of Bergman, for Tomas's profession was also that of Bergman's own father, a Lutheran minister who was transferred from his rural post to Stockholm the very year that the future director was born. And his name was Erik Bergman, making our Ingmar Erik's son, and while I am not in general fond of the dime store Freudianism that makes us look for details in the author's biography to decode their work, like every single piece of art ever made has a Shakespeare in Love behind it. But even I can't ignore it when the author himself is staring at me and grinning like a maniac, hoping I got his cunning joke. So, yes. Our protagonist, doubting Tomas, Erik's son. The vessel for Ingmar Bergman to pour all of his own anxieties about God apparently abandoning humanity to kill ourselves in the turbulent mid-century years of the Cold War.

I snark because I frankly find it all a bit precious, but the fact remains that even without all of this, Winter Light strikes me as quite a profound and affecting piece of cinema, just as the story of a character in a fictional drama. The plot is as spare as the mood suggested by the English title (the equally-good Swedish title, suggesting an entirely different set of thematic priorities, is The Communicants): Tomas is giving one of his lifeless, endless sermons to a crowd of virtually nobody (the opening sermon sequence is a good 20 minutes long, and the only reason it's not longer is that Bergman lost his nerve during the editing phase - he wanted it to be a punishing endurance test that ran for half the movie, which in its final cut is just over 80 minutes long). Bergman and editor Ulla Ryghe - whose first film, for Bergman or any other director, was this film's immediate predecessor, Through a Glass Darkly, and I think there's a hard, forceful quality to the cutting in these films not found in Bergman's earlier work - skillfully blend merciless wide shots of the yawning, empty church with probing medium close-ups of the parishioners, culminating in a remarkably composition with the faithful all crowd together to receive the sacrament of communion, as Tomas repetitively swivels between them, all in one tedious droning shot that captures all of them in the center of the frame, crunched together in a way that makes it seem all the more empty, that the whole congregation can fit into a box 1.37:1 frame with room left over; and at the same time, their huddle looks like people desperately clinging together for warmth and survival.

This marathon preaching sequence having ended, Tomas is approached by the Peterssons, Jonas (Max von Sydow) and Karin (Gunnel Lindblom) - the second Karin in as many films, sharing the name of Bergman's mother - with a quandary. Jonas, you see, is consumed with existential terror at the thought of mankind's destruction in nuclear war, and the recent news that China has built a nuclear bomb has proven too much for him. Tomas sends him away and asks him to come back. This leaves just one parishioner, his ex-lover Märta Lundberg (Ingrid Thulin), who speaks to him in kind tones and urges him to read the letter she has recently given him. Then she also leaves, and we get The Shot Of Thulin, with Märta standing in a mottled white void, reciting that whole letter right into the camera: loving Tomas and accusing him and giving up on him and demanding redress for all the pain he's caused her and acknowledging that no such apology is coming and it wouldn't matter if it did, looking right into us as she says it all. In the middle of it, she goes into a void within a void to reenact the time that she got a horrible rash and he was disgusted and this was the moment she realised his fallibility as a sympathetic, loving person, or that he didn't and would never love her, at any rate.

Tomas is in a morbid enough state of mind anyway that this seems to do very little to bother him, and this is when Jonas returns to discuss The Question: how do we reconcile our faith in a loving creator God with the misery around all the time. After hemming and hawing and looping around to the story of the atrocities he saw during the Spanish Civil War, Tomas finally announces that we don't, that the only way to make sense of any of this is to give up faith entirely and accept that God is gone, at best. Jonas leaves, Märta comes back, and a moment later, an old widow of the parish comes in to say that Jonas has killed himself with a shotgun.

This is the pivot point of Winter Light, rather than its climax; the remainder of the film basically turns into the Tomas and Märta road trip, as she tags along while he travels, besieged by an incoming head cold, to give an afternoon service at an even more run-down and empty church than his own. And this second half of the film is what sharpens the focus, not on poor Jonas's unsolvable questions, but on how Tomas and Märta (who was raised, and remains, an atheist) make sense of their own lives and feelings for each other in the face of all this grinding cosmic emptiness.

Fun, bubbly stuff - in a directorial career that has become shorthand for cinematic miserabilism, Winter Light is still Bergman's bleakest, most hopeless movie. This was in part his deliberate attempt to correct for the mistakes he saw in Through a Glass Darkly: that film left open the possibility that a loving God might still come back for us. It ends on a moment of ambivalent optimism. Winter Light ends, instead, on a moment of ambivalent pessimism, a preacher addressing himself with great authority and dignity to a congregation of nobody, a man who believes in nothing finally finding the audience to match.

I might as well say now as at any point that Winter Light is my favorite Bergman film: not the one that I think is best, and obviously not the one I "enjoy" the most, since there is nothing about that is even vaguely enjoyable, in any conventional sense. But I find it gripping in its austerity, its reduction of everything to a few barren miles of wintry scrubland over which the afternoon sun scrapes itself. The English title is an awfully good description of the contents: the "gimmick" of the film, if that's the word, is that Bergman wanted to evoke the precise way that sunlight shifts as it lowers itself to the horizon, in the winter months when night comes so early that afternoon has only just gotten itself started. Sven Nykvist apparently didn't quite understand what he was even being asked to do, though he did it splendidly well: it really is visually apparent how the light changes over the short period of time the movie covers (it's not quite real time, but it surely isn't more than two and a half hours or so), growing thinner and weaker even as it never blatantly changes what it's doing, as the shadowless glow seeping in through the windows and clouds removes all the most obvious markers of time and change in lighting. If it is possible to desaturate a film that's already black-and-white, Nykvist figured out how to do so; it is, however subtle, the most impressive work in his immensely impressive career, all the more so because he's not getting to rely on the Expressionist indulgences that he used in Through a Glass Darkly and in so many other things. This is, indeed, the most strictly naturalistic film Bergman ever made.

That means, in other words, that the film has a raw, artless, even ugly quality, one seeping in through the chilly, dry lighting, and manifest in the actors themselves. One of the many reasons Bergman gave to explain why the film was a tremendous bomb in Sweden (he expected nothing less even while making it) was that he took the beautiful Björnstrand and Thulin, and made them ugly. Or at least damned plain. Thulin perhaps gets the worse of it, with exaggerated bags under her eyes and chunky glasses that do nothing to frame her face, while Björnstrand spends the whole moving looking haggard and tired. And indeed he was: this is a tormented set, the most unpleasant shoot in the director's career by his estimation, and Bergman and Björnstrand's longstanding friendship very nearly didn't survive the experience. Certainly, he looks miserable and peevish, and this well suits his peevish character, a man so wrapped up in his own aghast anxieties about the world that he doesn't notice or care when he's steamrolling over those around him with his negative emotions, including people who most desperately look to him for guidance and comfort, or love and understanding. It is the most off-kilter role that the charming, urbane comedian Björnstrand played, and my favorite of his performances on top of it: with no channel for his natural charisma, the actor starts out as an empty space, and both he and Bergman use that emptiness as a canvas upon which to sketch in different gradations of doubt, unhappiness, or just irritation that it's cold and he's sick and nothing matters and he is feeling shitty about Jonas after all.

As great as Björnstrand is here, he has to settle for second-best. Thulin isn't just giving my favorite amongst her performances for Bergman, she's giving one of my favorite screen performances, period, and not only because of how much work she puts into that dumbfounding long-take monologue, differentiating between fury and love and depression using such little shifts in her expression and none at all in her tone of voice that I'm not always entirely sure what cued me to see them. In Bergman's cinema of close-ups, I can't name another one that so perfectly demonstrates the thrilling power of seeing actors going all the way small, not even the bravura close-up duels of Persona, three years and three films after this. The scene is devastating, accusing us as a proxy for accusing Tomas, and working in part because Thulin's performance works on us harder than it works on the sullen, unresponsive pastor.

But anyway, as I was saying: it's not just that scene. Märta is a phenomenal character, opaque where Tomas is a wide open book of faith in crisis. It's hard to say what the hell drives her: a desire to love and be loved, even if the only candidate is this joyless, short-tempered, and obviously insufficient man, but that doesn't explain everything, such as her commitment to the same empty rituals of faith that Tomas himself enacts - but where he does so out of habit, obligation, guilt, and fear, she has none of these things to explain. Thulin does not (maybe cannot) offer explanations for these things, but she gives us hints of Märta's own fears, no less neurotic and self-destroying than Tomas's though she does a much better job of not letting them splash all around the world, perhaps because she has more experience hiding them. Put it another way: while Thulin isn't letting us see her solution to Märta, she has obviously come up with an explanation for the character and is using it to ground her performance and tie it together, and so the effect of this is less "this is an opaque smudge of a character" than it is "how will I see past all the walls and mirrors she has put up to keep herself hidden?"

With performances like these (and others - Lindblom also gives my favorite performance of her career, a slash of human pain cutting through the over-intellectual Tomas and Märta), this film is the perfect vessel for all of those shots of faces, which Bergman uses to guide us through a film that remains stubbornly cinematic despite having been written strictly according to the logic of a theatrical play. Again, this is not always clever. It can be as simple as the shot/reverse-shot exchange between Tomas and Jonas in which the former man remains in medium shots until he suddenly jumps forward into a medium close-up at the moment he breaks and starts to spill his nihilistic fears into Jonas, all while Jonas himself remains locked in a slightly closer medium close-up; at the same time, von Sydow keeps his face locked in place while Björnstrand shifts and bends and looks generally quite uncomfortable in his own skin. Simple, but hardly easy, then, and the only way this works is because of the subtle gradations that the actors are giving the director and editor, to carve the footage of those actors into a battle of wills carried out in a push-pull of reactions and shifts in rhythm. There are a few more complicated shots, where we see two faces simultaneously, to be certain; this isn't a fully-developed strategy yet, but particularly as a way of keeping Tomas and the people he's failing in our brains simultaneously, it works quite well.

Still, it's not a pyrotechnic film - it's not The Silence or Persona. Frankly, it doesn't need to be. The film is spare and unforgiving, stripped down to its coldest, most fundamental elements of watery white light and anguished expressions and very little else. It is a bleak and blunt film, a cry of muffled pain rather than an aggressive cinematic spiral into complicated emotions. Really, the emotions aren't complicated here at all: we live in a world that makes no sense and is terrifying, and we're doing it alone, and this is all horrible to think about. It is, by Bergman standards, something like a primal scream, and I persist in finding it one of the most emotionally devastating films I have ever seen and ever expect to.

In the meantime, though, I was talking about the shot of Thulin's face, and if you've seen Winter Light, then you know why I feel so free and easy using the definite article. Because while there are many shots of her face in the movie, there's only one that's The Shot, or at least only two, given that The Shot is briefly interrupted by a cutaway, and I have no reason not to assume that we're seeing two different takes. The shot is a medium close-up, with Thulin framed exactly in the middle, staring directly into the lens, and she delivers a monologue in two merciless long takes - the first is about four and a half minutes long, the second about two minutes long. I think it is one of the pinnacles of sound cinema. The human face is, after all, one of the great cinematic subjects, and Bergman was, at this time, entering the phase of his career where he became quite possibly the greatest director of faces the medium had ever known. Visually, Winter Light is something of an exercise in the use of faces. There's the matter of how they go into editing rhythms: who are we looking at, what are they looking at, what do they think while they're looking at it, and all of that modulated by each line of dialogue and each shift in the dynamic between characters. And there is the matter of how they are positioned in the frame, and how that affects the psychologically expressive power that is the reason for close-ups and medium close-ups in the first place.

It's not necessarily the case that any of this is radical or transformative, for the most part; only that it is done extraordinarily well. Winter Light is generally described as being a film about living in a universe where God, if He exists, refuses to say anything to us, and that's definitely inside of it. But it is also, I think more importantly, about the pain of the characters coming to that realisation. That is to say: it's a character drama, not a philosophical tract, and this is something that I think people sometimes lose track of with Bergman films starting around this point. He is certainly a film artist playing around with The Big Ideas, but he's also someone whose films are always about characters who have been imbued with deep feeling and inner lives by incredibly gifted actors working at an eerily confident level with their director. We are always invited to watch first for the human story, second for the heavy, grandiose themes, and that's true even the themes are at their most crushing, as they are in Winter Light.

This is to say: yes, Winter Light is about God's silence. But really, it's about how his horrifying awareness of God's silence affects Pastor Tomas Ericsson (Gunnar Björnstrand), who preaches in a small town in central Sweden. Tomas has, for some time we can imagine, been going through the motions, having long since come to suspect that there is no plan, no divine guidance, no Godlike love; you could call him a doubting Tomas. And that's only half of what makes this the most groaning, political-cartoon-level symbolic name in all of Bergman, for Tomas's profession was also that of Bergman's own father, a Lutheran minister who was transferred from his rural post to Stockholm the very year that the future director was born. And his name was Erik Bergman, making our Ingmar Erik's son, and while I am not in general fond of the dime store Freudianism that makes us look for details in the author's biography to decode their work, like every single piece of art ever made has a Shakespeare in Love behind it. But even I can't ignore it when the author himself is staring at me and grinning like a maniac, hoping I got his cunning joke. So, yes. Our protagonist, doubting Tomas, Erik's son. The vessel for Ingmar Bergman to pour all of his own anxieties about God apparently abandoning humanity to kill ourselves in the turbulent mid-century years of the Cold War.

I snark because I frankly find it all a bit precious, but the fact remains that even without all of this, Winter Light strikes me as quite a profound and affecting piece of cinema, just as the story of a character in a fictional drama. The plot is as spare as the mood suggested by the English title (the equally-good Swedish title, suggesting an entirely different set of thematic priorities, is The Communicants): Tomas is giving one of his lifeless, endless sermons to a crowd of virtually nobody (the opening sermon sequence is a good 20 minutes long, and the only reason it's not longer is that Bergman lost his nerve during the editing phase - he wanted it to be a punishing endurance test that ran for half the movie, which in its final cut is just over 80 minutes long). Bergman and editor Ulla Ryghe - whose first film, for Bergman or any other director, was this film's immediate predecessor, Through a Glass Darkly, and I think there's a hard, forceful quality to the cutting in these films not found in Bergman's earlier work - skillfully blend merciless wide shots of the yawning, empty church with probing medium close-ups of the parishioners, culminating in a remarkably composition with the faithful all crowd together to receive the sacrament of communion, as Tomas repetitively swivels between them, all in one tedious droning shot that captures all of them in the center of the frame, crunched together in a way that makes it seem all the more empty, that the whole congregation can fit into a box 1.37:1 frame with room left over; and at the same time, their huddle looks like people desperately clinging together for warmth and survival.

This marathon preaching sequence having ended, Tomas is approached by the Peterssons, Jonas (Max von Sydow) and Karin (Gunnel Lindblom) - the second Karin in as many films, sharing the name of Bergman's mother - with a quandary. Jonas, you see, is consumed with existential terror at the thought of mankind's destruction in nuclear war, and the recent news that China has built a nuclear bomb has proven too much for him. Tomas sends him away and asks him to come back. This leaves just one parishioner, his ex-lover Märta Lundberg (Ingrid Thulin), who speaks to him in kind tones and urges him to read the letter she has recently given him. Then she also leaves, and we get The Shot Of Thulin, with Märta standing in a mottled white void, reciting that whole letter right into the camera: loving Tomas and accusing him and giving up on him and demanding redress for all the pain he's caused her and acknowledging that no such apology is coming and it wouldn't matter if it did, looking right into us as she says it all. In the middle of it, she goes into a void within a void to reenact the time that she got a horrible rash and he was disgusted and this was the moment she realised his fallibility as a sympathetic, loving person, or that he didn't and would never love her, at any rate.

Tomas is in a morbid enough state of mind anyway that this seems to do very little to bother him, and this is when Jonas returns to discuss The Question: how do we reconcile our faith in a loving creator God with the misery around all the time. After hemming and hawing and looping around to the story of the atrocities he saw during the Spanish Civil War, Tomas finally announces that we don't, that the only way to make sense of any of this is to give up faith entirely and accept that God is gone, at best. Jonas leaves, Märta comes back, and a moment later, an old widow of the parish comes in to say that Jonas has killed himself with a shotgun.

This is the pivot point of Winter Light, rather than its climax; the remainder of the film basically turns into the Tomas and Märta road trip, as she tags along while he travels, besieged by an incoming head cold, to give an afternoon service at an even more run-down and empty church than his own. And this second half of the film is what sharpens the focus, not on poor Jonas's unsolvable questions, but on how Tomas and Märta (who was raised, and remains, an atheist) make sense of their own lives and feelings for each other in the face of all this grinding cosmic emptiness.

Fun, bubbly stuff - in a directorial career that has become shorthand for cinematic miserabilism, Winter Light is still Bergman's bleakest, most hopeless movie. This was in part his deliberate attempt to correct for the mistakes he saw in Through a Glass Darkly: that film left open the possibility that a loving God might still come back for us. It ends on a moment of ambivalent optimism. Winter Light ends, instead, on a moment of ambivalent pessimism, a preacher addressing himself with great authority and dignity to a congregation of nobody, a man who believes in nothing finally finding the audience to match.

I might as well say now as at any point that Winter Light is my favorite Bergman film: not the one that I think is best, and obviously not the one I "enjoy" the most, since there is nothing about that is even vaguely enjoyable, in any conventional sense. But I find it gripping in its austerity, its reduction of everything to a few barren miles of wintry scrubland over which the afternoon sun scrapes itself. The English title is an awfully good description of the contents: the "gimmick" of the film, if that's the word, is that Bergman wanted to evoke the precise way that sunlight shifts as it lowers itself to the horizon, in the winter months when night comes so early that afternoon has only just gotten itself started. Sven Nykvist apparently didn't quite understand what he was even being asked to do, though he did it splendidly well: it really is visually apparent how the light changes over the short period of time the movie covers (it's not quite real time, but it surely isn't more than two and a half hours or so), growing thinner and weaker even as it never blatantly changes what it's doing, as the shadowless glow seeping in through the windows and clouds removes all the most obvious markers of time and change in lighting. If it is possible to desaturate a film that's already black-and-white, Nykvist figured out how to do so; it is, however subtle, the most impressive work in his immensely impressive career, all the more so because he's not getting to rely on the Expressionist indulgences that he used in Through a Glass Darkly and in so many other things. This is, indeed, the most strictly naturalistic film Bergman ever made.

That means, in other words, that the film has a raw, artless, even ugly quality, one seeping in through the chilly, dry lighting, and manifest in the actors themselves. One of the many reasons Bergman gave to explain why the film was a tremendous bomb in Sweden (he expected nothing less even while making it) was that he took the beautiful Björnstrand and Thulin, and made them ugly. Or at least damned plain. Thulin perhaps gets the worse of it, with exaggerated bags under her eyes and chunky glasses that do nothing to frame her face, while Björnstrand spends the whole moving looking haggard and tired. And indeed he was: this is a tormented set, the most unpleasant shoot in the director's career by his estimation, and Bergman and Björnstrand's longstanding friendship very nearly didn't survive the experience. Certainly, he looks miserable and peevish, and this well suits his peevish character, a man so wrapped up in his own aghast anxieties about the world that he doesn't notice or care when he's steamrolling over those around him with his negative emotions, including people who most desperately look to him for guidance and comfort, or love and understanding. It is the most off-kilter role that the charming, urbane comedian Björnstrand played, and my favorite of his performances on top of it: with no channel for his natural charisma, the actor starts out as an empty space, and both he and Bergman use that emptiness as a canvas upon which to sketch in different gradations of doubt, unhappiness, or just irritation that it's cold and he's sick and nothing matters and he is feeling shitty about Jonas after all.

As great as Björnstrand is here, he has to settle for second-best. Thulin isn't just giving my favorite amongst her performances for Bergman, she's giving one of my favorite screen performances, period, and not only because of how much work she puts into that dumbfounding long-take monologue, differentiating between fury and love and depression using such little shifts in her expression and none at all in her tone of voice that I'm not always entirely sure what cued me to see them. In Bergman's cinema of close-ups, I can't name another one that so perfectly demonstrates the thrilling power of seeing actors going all the way small, not even the bravura close-up duels of Persona, three years and three films after this. The scene is devastating, accusing us as a proxy for accusing Tomas, and working in part because Thulin's performance works on us harder than it works on the sullen, unresponsive pastor.

But anyway, as I was saying: it's not just that scene. Märta is a phenomenal character, opaque where Tomas is a wide open book of faith in crisis. It's hard to say what the hell drives her: a desire to love and be loved, even if the only candidate is this joyless, short-tempered, and obviously insufficient man, but that doesn't explain everything, such as her commitment to the same empty rituals of faith that Tomas himself enacts - but where he does so out of habit, obligation, guilt, and fear, she has none of these things to explain. Thulin does not (maybe cannot) offer explanations for these things, but she gives us hints of Märta's own fears, no less neurotic and self-destroying than Tomas's though she does a much better job of not letting them splash all around the world, perhaps because she has more experience hiding them. Put it another way: while Thulin isn't letting us see her solution to Märta, she has obviously come up with an explanation for the character and is using it to ground her performance and tie it together, and so the effect of this is less "this is an opaque smudge of a character" than it is "how will I see past all the walls and mirrors she has put up to keep herself hidden?"

With performances like these (and others - Lindblom also gives my favorite performance of her career, a slash of human pain cutting through the over-intellectual Tomas and Märta), this film is the perfect vessel for all of those shots of faces, which Bergman uses to guide us through a film that remains stubbornly cinematic despite having been written strictly according to the logic of a theatrical play. Again, this is not always clever. It can be as simple as the shot/reverse-shot exchange between Tomas and Jonas in which the former man remains in medium shots until he suddenly jumps forward into a medium close-up at the moment he breaks and starts to spill his nihilistic fears into Jonas, all while Jonas himself remains locked in a slightly closer medium close-up; at the same time, von Sydow keeps his face locked in place while Björnstrand shifts and bends and looks generally quite uncomfortable in his own skin. Simple, but hardly easy, then, and the only way this works is because of the subtle gradations that the actors are giving the director and editor, to carve the footage of those actors into a battle of wills carried out in a push-pull of reactions and shifts in rhythm. There are a few more complicated shots, where we see two faces simultaneously, to be certain; this isn't a fully-developed strategy yet, but particularly as a way of keeping Tomas and the people he's failing in our brains simultaneously, it works quite well.

Still, it's not a pyrotechnic film - it's not The Silence or Persona. Frankly, it doesn't need to be. The film is spare and unforgiving, stripped down to its coldest, most fundamental elements of watery white light and anguished expressions and very little else. It is a bleak and blunt film, a cry of muffled pain rather than an aggressive cinematic spiral into complicated emotions. Really, the emotions aren't complicated here at all: we live in a world that makes no sense and is terrifying, and we're doing it alone, and this is all horrible to think about. It is, by Bergman standards, something like a primal scream, and I persist in finding it one of the most emotionally devastating films I have ever seen and ever expect to.