Amicus Horror: The bad place

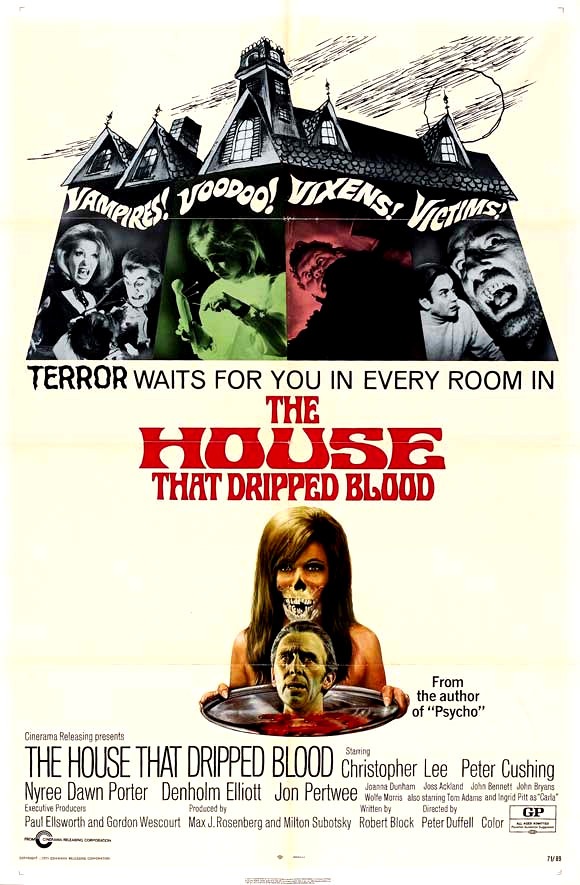

When people speak of Amicus Productions, what they're really speaking of, I think, is the set of films beginning with our present subject, 1971's The House That Dripped Blood. Between 1962 and 1970, Amicus produced 15 films on a variety of subjects, and only six of them were horror films (a number that already has to draft the sci-fi crime thriller Scream and Scream Again into the horror genre, at least somewhat against its will). Apparently the executives figured out somewhere along there that horror was paying the bills, though, because starting in 1971, the studio switched over to an all-hands-on-deck horror binge, releasing a staggering nine films in four years, every single one of them horror - more than half of them the anthology films that would shortly become Amicus's signature. This only changed with the total collapse of the British horror market, when the studio scaled back to a modest one film per year starting in 1975, releasing three consecutive Edgar Rice Burroughs adventure movies before quietly withering away and dying.

But let's not skip ahead to the gloomy future, but sit here in the glow of possibility that The House That Dripped Blood represented as the '70s loomed. Because this is a pretty damn terrific movie, a best-case scenario of what the Amicus-style anthology film could yield, as brought to life by certainly the best cast any of their movies had enjoyed to that point. Like the earlier Torture Garden, from 1967, the unifying theme is Robert Bloch, the iconic horror author who adapted the screenplay from four of his own short stories. I don't know if it's just that he was working with better stories this time, or if he had grown as a screenwriter, or if he was actually right all those times he bitched and moaned about Freddie Francis messing with his scripts, but The House That Dripped Blood is a major, across-the-board improvement on that film; I would say without a second of doubt that the worst segment here is better than the best segment there. It would be hard for me to say what, exactly has changed; the only concrete thing I can come up with is that Torture Garden was made up of O. Henry-ish tales of nasty-minded people getting their just and appropriate comeuppance, while The House That Dripped Blood favors less openly ironic twists, instead just going for little stabs of horror. It makes the thing feel less schematic.

Also making things feel less schematic, this film has a framework narrative that feels much more organic than such things tend to: the four segments are all positioned as flashbacks with in a detective mystery, and it almost could lull you into forgetting that this is an anthology film, rather than just a very bizarrely-structured detective story. The set-up is that the very irritable Detective Inspector Holloway (John Bennett) of Scotland Yard has been sent on what he clearly regards as a stupid time-waster of a case in the country, looking for an actor who's gone missing from the country house he's rented. Holloway heads to the office of A.J. Stoker (John Bryans), the leasing agent for the house, and from this very openly nervous and spooked man, he learns the horrible history of the place: apparently, this house appears has an ongoing history of terrible things happening to its residents, or on its grounds.

For example, a few tenants back, the house was occupied by Charles Hillyer (Denholm Elliott), a horror author, who moved there with his wife Alice (Joanna Dunham), in the hopes that it will provide a better working environment. And thus he sets to work on his new novel about a killer named Dominick, a hideous, deformed psychopath. In hardly any time at all, Charles thinks he's starting to see Dominick (Tom Adams), in the garden, in the far corners of rooms, and other places lying about. He meets with a psychologist, Dr. Andrews (Robert Lang), who immediately diagnoses a case of multiple personality disorder, suggesting that Charles has in fact begun embodying Dominick, in a weird fit of creative exertion. And this seems to be borne out when Charles is convinced that he sees Dominick attacking Alice, on for her to scream at him, in her frenzied panic declaring that he was attacking her himself. This all puts Charles in quite a fit of existential dread, of course, but there is more going on than meets the eye, and what is happening turns out to be both simpler than it seems as well as exactly what it seems.

The next resident was a gentle old retiree, Philip Grayson (Peter Cushing), who grows lonely in his isolation. Thus he's in an unusually receptive mood when he visits the wax museum in town, finding himself thoroughly unnerved by the beautiful wax statue of Salome, who eerily resembles a woman he used to love. The museum's owner (Wolfe Morris) explains the macabre history of the statue: it was modeled after his dead wife, who was executed for the crime of murdering his best friend. This freaks Philp out badly enough that he vows never to enter the museum again, which of course means that he will just days later. To his credit, it's not because he wants to; his ebullient friend and former romantic rival Neville Rogers (Joss Ackland, visiting for a short while, insists on going in. And he, too, is struck by the beautiful statue. I won't say where this goes, other than that the resemblance to the woman Philip and Neville once feuded over is a red herring; unfortunately, when Bloch wrote the story "Waxworks" in the late '30s, the movies had already made it very clear that wax statues of beautiful women could only lead to one place, and that's the place that Bloch takes us now.

Holloway is thoroughly unimpressed at this point, and leaves Stoker to find Sergeant Martin (John Malcolm), the local police officer on the case. Martin has his own tale of the house: it was, for a time, inhabited by a curt widower, John Reid (Christopher Lee), and his daughter Jane (Chloe Franks). To keep the girl's education going in this isolated spot, far from any school, John hires former teacher Ann Norton (Nyree Dawn Porter), who clearly finds the whole set-up troubling, and after not very long, she's able to articulate why: John seems to be a heartless tyrant, forbidding Jane from having toys or friends, and when Ann confronts him about this, the conversation eventually lands on his confession that he's glad his wife is dead, though he refuses to say why. Ann is of course convinced that he's an abuser and possibly a danger to Jane, never stopping to contemplate for a moment - who could? - that he might very well have an excellent reason for all of the things he does. And Ann's intervention in the family life is about to show exactly what happens when John's strict rules are broken even for a moment.

Martin then finally catches Holloway up on what has happened to that missing actor, Paul Henderson (Jon Pertwee). Paul is a horror icon, having appeared in, by his count, literally hundreds of movies, and he is currently shooting an insanely cheap and tawdry-looking thing that casts him as a Dracula knock-off. Rejecting the wardrobe team's vampire cloak as too fake-looking for words, he wanders into a strange occult curiosity shop, whose freaky, doddering proprietor (Geoffrey Bayldon) gives him a much richer-looking cloak for hardly any money. It comes with a catch, though: while wearing it, Paul apparently becomes a vampire, and while the effect isn't permanent, it doesn't need to be to cause him to be a danger to his co-star Carla Lynde (Ingrid Pitt), the buxom victim of his elegant vampire in the movie, and possibly about to become the same off-camera. Paul has the presence of mind to, you know, not wear the cloak, but he hasn't yet grappled with the hints that there is something or somebody who wanted him to find it, and is in possession of a Plan B.

Not a genuinely weak effort in the bunch, though only "Sweets to the Sweet" - the Chris Lee one - is entirely free of some contrived writing ("Method for Murder" - the Denholm Elliott one - handles the psychologist gracelessly; "Waxworks" has the odd red herring about the woman the two men both loved, and an apparent faith that we aren't aware of its clichéd twist ending from the outset; "The Cloak" has a twist that renders much of what we've already seen to be unnecessary and unfairly misleading). Every single one of them also has some great strengths to counterbalance. The greatest strength is the cast: this is a terrific set of actors, with the Elliott/Cushing/Lee/Pertwee quartet nicely filled out by some excellent support. And so we get to unexpected pleasures like the way that Cushing and Ackland bring in some post-middle-age melancholy to their story (Cushing's wife was dying at the time of the production, which he had to be essentially press-ganged into joining; it's quite clear he was using that to fuel his character's gentle, awfully lonely sadness), or Pitt's revelation of a knack for comic timing that I would never have expected from the films she did for Hammer around the same time.

It helps as well that, in my estimation at least, every sequence improves upon the last. "Method for Murder" is just a nice grotty melodrama with a terrifically creepy-looking monster; "Waxworks" deepens its trite scenario with those outstanding performances. Things really start to heat up with "Sweets for the Sweet", which makes fantastic use of Lee's natural prickliness to point us in the wrong direction early on. There's an uncomfortable savagery coursing underneath this story as well, a sense of something actually broken and cruel. And there is, it's just not what we think it is, and the pungent meanness of the last 90 seconds or so, verging into nihilism, hits hard in a way that one would never expect of something as light and frivolous as a British horror film in 1971 that was treated as an all-ages spook show in the United States (where it was a far bigger hit than in its home country).

But "The Cloak" is where things get really magical. This is nothing less than a self-parody, a flippant story about the kind of people who crank out budget Gothic horror movies, and in particular the self-important actors who get caught in such movies. Pertwee is absolutely phenomenal as the annoyed, egocentric Paul, a top-class professional who refuses to let the impoverished resources of low-budget horror get in the way of putting together a dignified, convincing show for the audience. He's both fatuous and admirable, a snappish actor of no observable talent but considerable sincerity, and Pertwee plays this with a healthy dash of unrestrained camp, in a performance he based on his friend Lee (there's even a deadpan joke at Lee's expense, as Paul sings the praises of the Béla Lugosi Dracula, but not the garbage starring "this new fellow").

It's the kind of thing that I typically find obnoxiously knowing and self-satisfied, and I really couldn't say why it worked for me here; maybe because it flows so naturally from the prim Englishness common to all Amicus films. At any rate, it's hilarious when it needs to be, legitimately morbid and creepy when it needs to be that instead. In a film that mostly does great work balancing tones and moods,"The Cloak" is a pretty terrific tonal balancing act all by itself.

For this, we can presumably thank director Peter Duffell, almost exclusively a television director before and after this (he took the job after Freddie Francis had to pass for contractual reasons). This is, indeed, his only film of any note, and I find that sad: the clarity and artlessness of TV training works very much to the benefit of the first and fourth segments, and it at least doesn't damage the second and third. His images are crisp and to the point, making the intrusions of shocking moments feel genuinely unexpected by virtue of how the film simply barrels into them (especially the early appearance of Dominick), and leaving plenty of room for humor in the fourth segment, without turning it into insubstantial joking around. He is, to put it simply, a perfect director for a film with limited resources, relying on a few reliable ways to slam into the viewer rather than craft involved scenes that let the mood sink into us. Given that this is, after all, something of a tacky B-movie, that directness is not at all unwelcome. Indeed, it's a big part of why, despite its relative lack of grace, The House That Dripped Blood is so much more enjoyable than most of Amicus's horror up to that point: it gets to delight us with a showman's zeal for the garish and memorable. If we take the point of these anthologies as being just a vessel to funnel playfully spook stories our way, with energy and horrifying flair, it's hard to imagine any of them improving on this film's baseline.

But let's not skip ahead to the gloomy future, but sit here in the glow of possibility that The House That Dripped Blood represented as the '70s loomed. Because this is a pretty damn terrific movie, a best-case scenario of what the Amicus-style anthology film could yield, as brought to life by certainly the best cast any of their movies had enjoyed to that point. Like the earlier Torture Garden, from 1967, the unifying theme is Robert Bloch, the iconic horror author who adapted the screenplay from four of his own short stories. I don't know if it's just that he was working with better stories this time, or if he had grown as a screenwriter, or if he was actually right all those times he bitched and moaned about Freddie Francis messing with his scripts, but The House That Dripped Blood is a major, across-the-board improvement on that film; I would say without a second of doubt that the worst segment here is better than the best segment there. It would be hard for me to say what, exactly has changed; the only concrete thing I can come up with is that Torture Garden was made up of O. Henry-ish tales of nasty-minded people getting their just and appropriate comeuppance, while The House That Dripped Blood favors less openly ironic twists, instead just going for little stabs of horror. It makes the thing feel less schematic.

Also making things feel less schematic, this film has a framework narrative that feels much more organic than such things tend to: the four segments are all positioned as flashbacks with in a detective mystery, and it almost could lull you into forgetting that this is an anthology film, rather than just a very bizarrely-structured detective story. The set-up is that the very irritable Detective Inspector Holloway (John Bennett) of Scotland Yard has been sent on what he clearly regards as a stupid time-waster of a case in the country, looking for an actor who's gone missing from the country house he's rented. Holloway heads to the office of A.J. Stoker (John Bryans), the leasing agent for the house, and from this very openly nervous and spooked man, he learns the horrible history of the place: apparently, this house appears has an ongoing history of terrible things happening to its residents, or on its grounds.

For example, a few tenants back, the house was occupied by Charles Hillyer (Denholm Elliott), a horror author, who moved there with his wife Alice (Joanna Dunham), in the hopes that it will provide a better working environment. And thus he sets to work on his new novel about a killer named Dominick, a hideous, deformed psychopath. In hardly any time at all, Charles thinks he's starting to see Dominick (Tom Adams), in the garden, in the far corners of rooms, and other places lying about. He meets with a psychologist, Dr. Andrews (Robert Lang), who immediately diagnoses a case of multiple personality disorder, suggesting that Charles has in fact begun embodying Dominick, in a weird fit of creative exertion. And this seems to be borne out when Charles is convinced that he sees Dominick attacking Alice, on for her to scream at him, in her frenzied panic declaring that he was attacking her himself. This all puts Charles in quite a fit of existential dread, of course, but there is more going on than meets the eye, and what is happening turns out to be both simpler than it seems as well as exactly what it seems.

The next resident was a gentle old retiree, Philip Grayson (Peter Cushing), who grows lonely in his isolation. Thus he's in an unusually receptive mood when he visits the wax museum in town, finding himself thoroughly unnerved by the beautiful wax statue of Salome, who eerily resembles a woman he used to love. The museum's owner (Wolfe Morris) explains the macabre history of the statue: it was modeled after his dead wife, who was executed for the crime of murdering his best friend. This freaks Philp out badly enough that he vows never to enter the museum again, which of course means that he will just days later. To his credit, it's not because he wants to; his ebullient friend and former romantic rival Neville Rogers (Joss Ackland, visiting for a short while, insists on going in. And he, too, is struck by the beautiful statue. I won't say where this goes, other than that the resemblance to the woman Philip and Neville once feuded over is a red herring; unfortunately, when Bloch wrote the story "Waxworks" in the late '30s, the movies had already made it very clear that wax statues of beautiful women could only lead to one place, and that's the place that Bloch takes us now.

Holloway is thoroughly unimpressed at this point, and leaves Stoker to find Sergeant Martin (John Malcolm), the local police officer on the case. Martin has his own tale of the house: it was, for a time, inhabited by a curt widower, John Reid (Christopher Lee), and his daughter Jane (Chloe Franks). To keep the girl's education going in this isolated spot, far from any school, John hires former teacher Ann Norton (Nyree Dawn Porter), who clearly finds the whole set-up troubling, and after not very long, she's able to articulate why: John seems to be a heartless tyrant, forbidding Jane from having toys or friends, and when Ann confronts him about this, the conversation eventually lands on his confession that he's glad his wife is dead, though he refuses to say why. Ann is of course convinced that he's an abuser and possibly a danger to Jane, never stopping to contemplate for a moment - who could? - that he might very well have an excellent reason for all of the things he does. And Ann's intervention in the family life is about to show exactly what happens when John's strict rules are broken even for a moment.

Martin then finally catches Holloway up on what has happened to that missing actor, Paul Henderson (Jon Pertwee). Paul is a horror icon, having appeared in, by his count, literally hundreds of movies, and he is currently shooting an insanely cheap and tawdry-looking thing that casts him as a Dracula knock-off. Rejecting the wardrobe team's vampire cloak as too fake-looking for words, he wanders into a strange occult curiosity shop, whose freaky, doddering proprietor (Geoffrey Bayldon) gives him a much richer-looking cloak for hardly any money. It comes with a catch, though: while wearing it, Paul apparently becomes a vampire, and while the effect isn't permanent, it doesn't need to be to cause him to be a danger to his co-star Carla Lynde (Ingrid Pitt), the buxom victim of his elegant vampire in the movie, and possibly about to become the same off-camera. Paul has the presence of mind to, you know, not wear the cloak, but he hasn't yet grappled with the hints that there is something or somebody who wanted him to find it, and is in possession of a Plan B.

Not a genuinely weak effort in the bunch, though only "Sweets to the Sweet" - the Chris Lee one - is entirely free of some contrived writing ("Method for Murder" - the Denholm Elliott one - handles the psychologist gracelessly; "Waxworks" has the odd red herring about the woman the two men both loved, and an apparent faith that we aren't aware of its clichéd twist ending from the outset; "The Cloak" has a twist that renders much of what we've already seen to be unnecessary and unfairly misleading). Every single one of them also has some great strengths to counterbalance. The greatest strength is the cast: this is a terrific set of actors, with the Elliott/Cushing/Lee/Pertwee quartet nicely filled out by some excellent support. And so we get to unexpected pleasures like the way that Cushing and Ackland bring in some post-middle-age melancholy to their story (Cushing's wife was dying at the time of the production, which he had to be essentially press-ganged into joining; it's quite clear he was using that to fuel his character's gentle, awfully lonely sadness), or Pitt's revelation of a knack for comic timing that I would never have expected from the films she did for Hammer around the same time.

It helps as well that, in my estimation at least, every sequence improves upon the last. "Method for Murder" is just a nice grotty melodrama with a terrifically creepy-looking monster; "Waxworks" deepens its trite scenario with those outstanding performances. Things really start to heat up with "Sweets for the Sweet", which makes fantastic use of Lee's natural prickliness to point us in the wrong direction early on. There's an uncomfortable savagery coursing underneath this story as well, a sense of something actually broken and cruel. And there is, it's just not what we think it is, and the pungent meanness of the last 90 seconds or so, verging into nihilism, hits hard in a way that one would never expect of something as light and frivolous as a British horror film in 1971 that was treated as an all-ages spook show in the United States (where it was a far bigger hit than in its home country).

But "The Cloak" is where things get really magical. This is nothing less than a self-parody, a flippant story about the kind of people who crank out budget Gothic horror movies, and in particular the self-important actors who get caught in such movies. Pertwee is absolutely phenomenal as the annoyed, egocentric Paul, a top-class professional who refuses to let the impoverished resources of low-budget horror get in the way of putting together a dignified, convincing show for the audience. He's both fatuous and admirable, a snappish actor of no observable talent but considerable sincerity, and Pertwee plays this with a healthy dash of unrestrained camp, in a performance he based on his friend Lee (there's even a deadpan joke at Lee's expense, as Paul sings the praises of the Béla Lugosi Dracula, but not the garbage starring "this new fellow").

It's the kind of thing that I typically find obnoxiously knowing and self-satisfied, and I really couldn't say why it worked for me here; maybe because it flows so naturally from the prim Englishness common to all Amicus films. At any rate, it's hilarious when it needs to be, legitimately morbid and creepy when it needs to be that instead. In a film that mostly does great work balancing tones and moods,"The Cloak" is a pretty terrific tonal balancing act all by itself.

For this, we can presumably thank director Peter Duffell, almost exclusively a television director before and after this (he took the job after Freddie Francis had to pass for contractual reasons). This is, indeed, his only film of any note, and I find that sad: the clarity and artlessness of TV training works very much to the benefit of the first and fourth segments, and it at least doesn't damage the second and third. His images are crisp and to the point, making the intrusions of shocking moments feel genuinely unexpected by virtue of how the film simply barrels into them (especially the early appearance of Dominick), and leaving plenty of room for humor in the fourth segment, without turning it into insubstantial joking around. He is, to put it simply, a perfect director for a film with limited resources, relying on a few reliable ways to slam into the viewer rather than craft involved scenes that let the mood sink into us. Given that this is, after all, something of a tacky B-movie, that directness is not at all unwelcome. Indeed, it's a big part of why, despite its relative lack of grace, The House That Dripped Blood is so much more enjoyable than most of Amicus's horror up to that point: it gets to delight us with a showman's zeal for the garish and memorable. If we take the point of these anthologies as being just a vessel to funnel playfully spook stories our way, with energy and horrifying flair, it's hard to imagine any of them improving on this film's baseline.