Amicus Horror: Bee ware

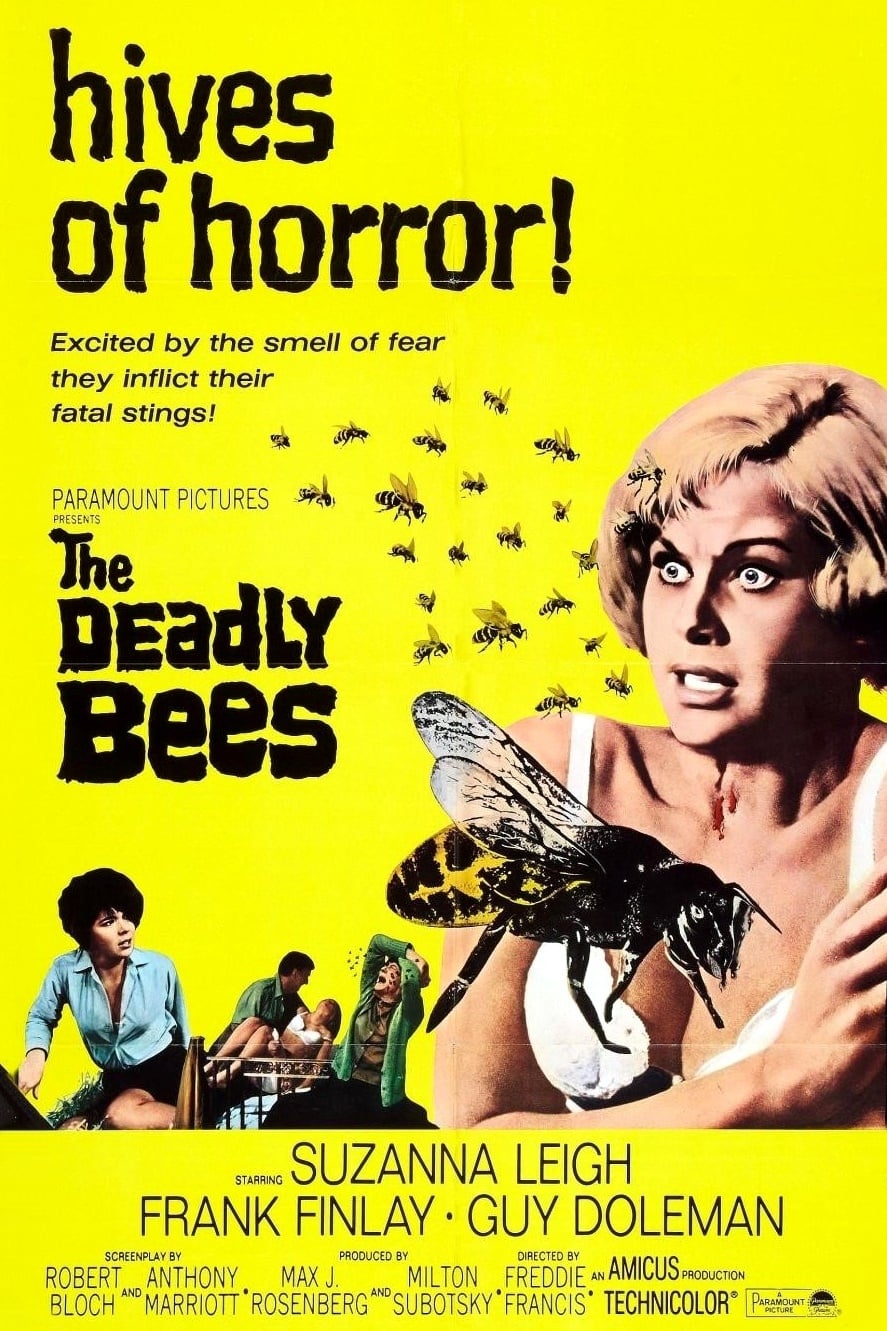

The Deadly Bees, from 1966, isn't really a very good movie - it's fine. It's got some largely good and charming moments, some dumb moments, and some aggressively bad effects. But it has a longstanding reputation for being terrible beyond words, which comes I think from two different things. First, credited screenwriter Robert Bloch had some extremely hostile things to say about director Freddie Francis, who had the screenplay substantially rewritten by Anthony Marriott without telling Bloch, or producers Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. Now, Bloch was a bit of a complainer, and also not really an especially good writer (as far as I can tell, his reputation coasts substantially on the film adaptation of Psycho, which he didn't write, and which improves significantly on his novel), but I'm willing to suppose that he might have had a point in suggesting that Francis and Marriott ruined his movie: nothing in Marriott's career suggests any affinity for making a horror-thriller-murder mystery of this sort, and some of the worst parts of the finished script are in line with his career. Still, "ruined" is harsh, and while it may well be that Gerald Heard's novel A Taste for Honey was a masterpiece with one of the all-time great movies waiting inside of inside of it, it's still a story about a man who uses fear pheromones to command an army of killer bees. I have my doubts that there was a non-silly version of this story at any point in its pre-production.

The second thing is that The Deadly Bees was riffed in a 1998 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, and that always has a way of putting some dents in a movie's reputation, deserved or not. Hell, there are people who think that Mario Bava's terrific spy film Diabolik is a bad movie, just because it was on MST3K.

Now, I'm not going to go and tell you that The Deadly Bees is actually a secret masterpiece and shame on Bloch and the folks at Best Brains. It is certainly the weakest of any of Amicus Productions' horror films up to that point (if it indeed it belongs among their number; but that's conventionally where it has been slotted, so I'll live with that convention), with some excessively clunky storytelling that's much more about making sure the characters are in place for the narrative beats than it is about making sure that the characters are rational or coherent. This gets much, much worse as it nears the "astonishing" "twist" ending, huffing and puffing its way through some ten minutes of purely mechanical busywork, along with a completely indecent amount of flashbacks to do not much else than bodily shove the running time over 80 minutes (the second big flashback montage ends at a point that we saw literally about 90 seconds before the flashback started). Whichever of Bloch, Marriott and Heard is responsible for it, The Deadly Bees ultimately takes the form of a murder mystery, and it is very cumbersome about the generic requirements this entails, deploying plot developments with an astonishingly lack of grace, or even the smallest effort to hide what it's doing.

Still, there's something enjoyable beneath all of this. There's a very tweedy, stereotypical English energy to the setting and the characters, and the film seems aware that it's dabbling in stereotypes. Actually, the whole thing kind of builds itself up as a culture clash between two different kinds of English stereotype. Vicki Robbins (Suzanna Leigh) is the hip swinging London pop star, who we meet as she collapses while filming a TV appearance (she goes on right after The Birds, a rock group whose main claims to fame are being the first home of guitarist Ronnie Wood, and having a name that makes you do a double-take before you spot the missing Y) - Francis directs this sequence with some great use of woozy first-person camera angles to show just how panicked and heavy she's feeling right before she goes down. The diagnosis is exhaustion from the pace of modern living, and the treatment is to spend some time on Seagull Island, at the home of her doctor's friend, standoffish beekeeper Ralph Hargrove (Guy Doleman). Seagull Island is basically Peyton Place: Hargrove and his wife Mary (Catherine Finn) despise each other openly, and he makes no secret of flirting with women around town, including Doris (Katy Wild), the woman the Hargroves have hired to help deal with Vicki. Also, the Hargroves' neighbor, H.W. Manfred (Frank Finlay), is also a beekeeper, a much meeker and bookish sort, and the rivalry between the two is palpable from the moment Vicki arrives on the island.

Something we know that only one of the characters does at this point: there's been a mysterious crank sending letters to the police on the mainland, threatening to unleash an army of deadly bees on the world. They have taken this with the absolutely minimum possible amount of gravity, but having seen the title, we are presumably on alert. Or maybe not. It doesn't move very fast, The Deadly Bees, and the parts of it that are the most in Amicus's genre wheelhouse - the violent, chaotic bee attacks - are easily the worst parts of the movie, largely on account of how jaw-droppingly shitty the effects are. Mostly, the bee attacks are depicted just by superimposing shots of bee swarms that have been tinted bright yellow; sometimes this involves gluing plastic flies (not plastic bees, plastic flies) onto the faces of whatever person is getting attacked, most ridiculously and ruinously in the case of Mary Hargrove's death. At least once, they literally just filmed tea leaves swirling in a spiral, and superimposed that. The bee attacks are, I mean to say, horrendous, and if that's the basis of the argument that this is a truly dreadful film, I completely get it.

But it's not really a killer bee film, it's a laconic murder mystery with a dash of what passes for science fiction in this rural British setting. Because, of course, some human actor is controlling the bees, and the film's two questions are how, and who. "How" is ludicrous. "Who" is pretty simple, given that there are so few characters with lines in the whole movie. Still, if the murder mystery isn't doing much, the "laconic" part is actually kind of appealing, I think. The film is very small and domestic, hopping from cottage to cottage and spending much of its time on a very cozy-looking set that absolutely refuses to convince us that it's a farm. And there's something that I, at least, find enjoyable about the light soap opera, mostly because of how unmelodramatic and sincerely the actors play it. There are no great performances here, and at least one very bad one - Finlay's roll was written for Boris Karloff, much as Doleman's was written for Christopher Lee, and both men play the parts that way. Doleman is perfectly fine; all he's really doing is being curt and snappish. Finlay, though, is much too cute, and it doesn't help matters at all that he's been attacked by some astonishingly unconvincing old age make-up, which mostly just makes it look like they spray-painted his hair. So maybe he never had a fair chance to survive in the first place. But he definitely doesn't survive, turning every one of his scenes into mannered, fiddly comedy bits, playing a caricature of an English academic with maximum fumbling and stammering.

I'm almost willing to say that swapping out Finlay would, all by itself, be enough to haul The Deadly Bees across the line separating "this didn't work" from "this worked okay, I guess". It's always doomed to be a very little, very silly film, but mostly the cast seems to know this and play it accordingly. Francis, for his part, continues to direct the way he directed all of his Amicus films, blithely ignoring the fact that they're cheap horror quickies, and imbuing them with an inquisitive feeling of depth, with every new set feeling like an array of shadowboxes upon shadowboxes, leading us into different nooks and crannies as we scan across them. And this is effectively contrasted with the flatter insert shots of reactions, mostly of Leigh, who is an extremely able straight man for all of the goofy kitsch surrounding her. It's not a visual masterpiece - cinematographer John Wilcox tends to keep the lighting bright and even, and this means there's no heavy mysterious atmosphere, and I would imagine that given the pastoral vibe of so much of the film, nobody much wanted that atmosphere. But it's well-built, treating its silly content with gravity and sincerity. While this is clearly a supbar effort for Amicus by the standards it set for itself, it's also the kind of thing that shows just how good the studio's first few years were, if something like this could be one of its obvious failures.

The second thing is that The Deadly Bees was riffed in a 1998 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, and that always has a way of putting some dents in a movie's reputation, deserved or not. Hell, there are people who think that Mario Bava's terrific spy film Diabolik is a bad movie, just because it was on MST3K.

Now, I'm not going to go and tell you that The Deadly Bees is actually a secret masterpiece and shame on Bloch and the folks at Best Brains. It is certainly the weakest of any of Amicus Productions' horror films up to that point (if it indeed it belongs among their number; but that's conventionally where it has been slotted, so I'll live with that convention), with some excessively clunky storytelling that's much more about making sure the characters are in place for the narrative beats than it is about making sure that the characters are rational or coherent. This gets much, much worse as it nears the "astonishing" "twist" ending, huffing and puffing its way through some ten minutes of purely mechanical busywork, along with a completely indecent amount of flashbacks to do not much else than bodily shove the running time over 80 minutes (the second big flashback montage ends at a point that we saw literally about 90 seconds before the flashback started). Whichever of Bloch, Marriott and Heard is responsible for it, The Deadly Bees ultimately takes the form of a murder mystery, and it is very cumbersome about the generic requirements this entails, deploying plot developments with an astonishingly lack of grace, or even the smallest effort to hide what it's doing.

Still, there's something enjoyable beneath all of this. There's a very tweedy, stereotypical English energy to the setting and the characters, and the film seems aware that it's dabbling in stereotypes. Actually, the whole thing kind of builds itself up as a culture clash between two different kinds of English stereotype. Vicki Robbins (Suzanna Leigh) is the hip swinging London pop star, who we meet as she collapses while filming a TV appearance (she goes on right after The Birds, a rock group whose main claims to fame are being the first home of guitarist Ronnie Wood, and having a name that makes you do a double-take before you spot the missing Y) - Francis directs this sequence with some great use of woozy first-person camera angles to show just how panicked and heavy she's feeling right before she goes down. The diagnosis is exhaustion from the pace of modern living, and the treatment is to spend some time on Seagull Island, at the home of her doctor's friend, standoffish beekeeper Ralph Hargrove (Guy Doleman). Seagull Island is basically Peyton Place: Hargrove and his wife Mary (Catherine Finn) despise each other openly, and he makes no secret of flirting with women around town, including Doris (Katy Wild), the woman the Hargroves have hired to help deal with Vicki. Also, the Hargroves' neighbor, H.W. Manfred (Frank Finlay), is also a beekeeper, a much meeker and bookish sort, and the rivalry between the two is palpable from the moment Vicki arrives on the island.

Something we know that only one of the characters does at this point: there's been a mysterious crank sending letters to the police on the mainland, threatening to unleash an army of deadly bees on the world. They have taken this with the absolutely minimum possible amount of gravity, but having seen the title, we are presumably on alert. Or maybe not. It doesn't move very fast, The Deadly Bees, and the parts of it that are the most in Amicus's genre wheelhouse - the violent, chaotic bee attacks - are easily the worst parts of the movie, largely on account of how jaw-droppingly shitty the effects are. Mostly, the bee attacks are depicted just by superimposing shots of bee swarms that have been tinted bright yellow; sometimes this involves gluing plastic flies (not plastic bees, plastic flies) onto the faces of whatever person is getting attacked, most ridiculously and ruinously in the case of Mary Hargrove's death. At least once, they literally just filmed tea leaves swirling in a spiral, and superimposed that. The bee attacks are, I mean to say, horrendous, and if that's the basis of the argument that this is a truly dreadful film, I completely get it.

But it's not really a killer bee film, it's a laconic murder mystery with a dash of what passes for science fiction in this rural British setting. Because, of course, some human actor is controlling the bees, and the film's two questions are how, and who. "How" is ludicrous. "Who" is pretty simple, given that there are so few characters with lines in the whole movie. Still, if the murder mystery isn't doing much, the "laconic" part is actually kind of appealing, I think. The film is very small and domestic, hopping from cottage to cottage and spending much of its time on a very cozy-looking set that absolutely refuses to convince us that it's a farm. And there's something that I, at least, find enjoyable about the light soap opera, mostly because of how unmelodramatic and sincerely the actors play it. There are no great performances here, and at least one very bad one - Finlay's roll was written for Boris Karloff, much as Doleman's was written for Christopher Lee, and both men play the parts that way. Doleman is perfectly fine; all he's really doing is being curt and snappish. Finlay, though, is much too cute, and it doesn't help matters at all that he's been attacked by some astonishingly unconvincing old age make-up, which mostly just makes it look like they spray-painted his hair. So maybe he never had a fair chance to survive in the first place. But he definitely doesn't survive, turning every one of his scenes into mannered, fiddly comedy bits, playing a caricature of an English academic with maximum fumbling and stammering.

I'm almost willing to say that swapping out Finlay would, all by itself, be enough to haul The Deadly Bees across the line separating "this didn't work" from "this worked okay, I guess". It's always doomed to be a very little, very silly film, but mostly the cast seems to know this and play it accordingly. Francis, for his part, continues to direct the way he directed all of his Amicus films, blithely ignoring the fact that they're cheap horror quickies, and imbuing them with an inquisitive feeling of depth, with every new set feeling like an array of shadowboxes upon shadowboxes, leading us into different nooks and crannies as we scan across them. And this is effectively contrasted with the flatter insert shots of reactions, mostly of Leigh, who is an extremely able straight man for all of the goofy kitsch surrounding her. It's not a visual masterpiece - cinematographer John Wilcox tends to keep the lighting bright and even, and this means there's no heavy mysterious atmosphere, and I would imagine that given the pastoral vibe of so much of the film, nobody much wanted that atmosphere. But it's well-built, treating its silly content with gravity and sincerity. While this is clearly a supbar effort for Amicus by the standards it set for itself, it's also the kind of thing that shows just how good the studio's first few years were, if something like this could be one of its obvious failures.