Stimulus package

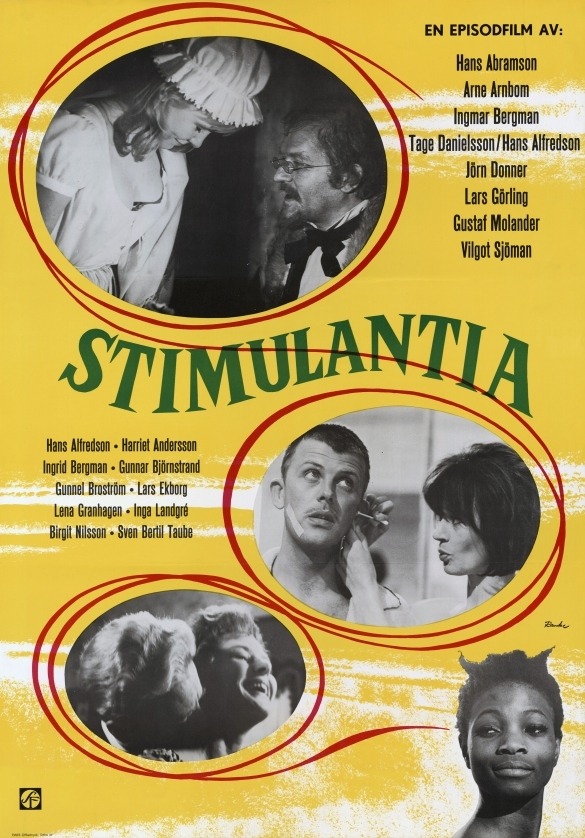

These days, when the 1967 Stimulantia comes up - something it is powerfully unlikely to ever do - it's almost certainly in the context of being the one anthology film that Ingmar Bergman contributed a segment to, right in the heart of his international heyday in the 1960s (it nestles in his career during the one-year gap between the legendary Persona and the excellent Hour of the Wolf). In a sense, that's not fair: Bergman's segment is certainly not the best, and it's probably not the one that seemed like The Big Deal in Sweden at the time (I cannot, however, find the smallest shred of evidence as to how the film was marketed, only that it was a box office disappointment). But I wouldn't want to go too far down that path, because at some point it would lead to the implication that this is mostly a good film outside of Bergman's segment, and that would be a bad thing for me to imply.

The film was pitched, apparently, by Bergman and TV producer/occasional director Arne Arnbom, which is fucking insane, given that their two segments are the ones with the strongest "*sigh* fine, I'll make a little short segment for your movie, I just happened to have this footage lying around" vibe in the whole picture. The concept is that several well-regarded directors in the Svensk Filmindustri sphere of influence were given one prompt - "what stimulates you?" - and around 10 or 12 minutes to answer that question (except for the penultimate segment, by the old master Gustaf Molander, who came out of retirement to make his sequence, and ended his career with this film; that was good enough reason to give him twice as much time as everyone else). Most of the segments are sincere enough, though most of them also feel like the directors wanted to get them over without too much fuss, and the whole movie has a general "good enough" vibe, which isn't enough to keep it afloat in the face of the couple of segments that are decisively less than good enough. But we'll get to those soon enough.

"Upptäckten" ["The Discovery"]

Written and directed by Hans Abramson

Notwithstanding all the things I just said, this actually must have taken Abramson some effort to put together. He acerbically notes that what "stimulates" him are sex and drugs, and he'd rather take the meaning loosely: what stimulates him is the memory of childhood, and specifically the childhood of Charlie Chaplin, who was himself inspired by childhood to become the filmmaker and movie star who charmed the world. And so Abramson's sequence is a documentary investigation into the place where Chaplin was born, on a street that no longer exists. As he pokes his camera around, inquiring of the locals if they know anything about the genius who arose from the place, Abramson's focus drifts: he starts to find what is vital and human in the neighborhood as it is presently constituted, not as it serves as the place where history took place. It's certainly a very sweet little piece, and it meanders in a way that feels very honest and inquisitive, but it ultimately just sort of lies there, harmlessly looking at the world and not doing anything else. The willingness to just let the world spill out in front of the camera is a good impulse, but the need to start by framing this as a Chaplin homage means that it can only spend literally a couple of minutes doing that; up to that point, it's just an unproductive fan tribute, and after that it simply has no time to accrue any weight. A pleasant way to start, but not anything else.

"Det var en gång två älskande..." ["Once Upon a Time There Were Two Lovers"]

Written and directed by Jörn Donner

Donner, like Abramson, begins by conceding that all stimulation is ultimately about sex; unlike Abramson, he does something with it, and the result is decisively my favorite thing here. Harriet Andersson and Sven-Bertil Taube play a couple about to have sex in a hotel room, but first, they go through an extensive routine of cleaning-up and prepping, with the unnamed "she" accidentally wounding the unnamed "he" in the process, but it's all in good flirty fun. The problem is that they get so involved in getting ready for sex that they wear themselves out without having sex.

That's cute and all, but the real strength of the segement lies in Donner's straight-faced comic tone. This is something like a what-if exercise in what realistic 1960s art house explorations of the human libido would look like if they were made like silent stag films, with some editing on loan from the '60s New Waves. It's punchy and even, dare I say it, a little zany, benefiting enormously from Andersson and Taube's chemistry and willingness to dive headfirst into the silliness without self-consciousness, or without sacrificing the sexy charge of the material. It's very light and playful, and formally inventive enough to feel like Donner was thinking a bit harder than anyone else here about the possibilities of the Stimulantia project, not just its limitations.

"Konfrontationer" ["Confrontations"]

Written and directed by Lars Görling

Görling's introduction (these films all start with introductions by the director) spends a whole lot of time feeling his way through linguistic philosophy, name-dropping Wittgenstein, all to explain why it's going to be such a very weird collage of ideas and images he's about to drop on us, at which point we are treated to: a montage of stills and moving images about formula racing. And the profundities don't stop here, either: Görling continues to muse about the appeal of racing, the death-drive of it, the power and eroticism of the care rattling one's body, and so on. And it's, like a lot to try to pack onto these images, though i think there's at least a possibility that it's tongue-in-cheek. The montage itself is extremely well-done, and the abstract poetry of the racing, as assembled through these piecemeal images and fragments of moments, feels like it's getting at the expression deeper than words that Görling seems to be talking about. But it would, frankly, have gotten there more beautifully and convincingly without him prattling.

"Daniel"

Written and directed by Ingmar Bergman

Speaking of pretentiously loading up one's delicate little visual collage with portentous verbiage: Bergman is clearly aware that he's Famous International Art Director Ingmar Bergman, and so he packs some real grave weight into his introduction, telling us that we're about to see the curated images of his eighth child (of nine) and lastborn son, Daniel Sebastian Bergman, filmed between the pregnancy of his mother, Bergman's fourth wife, Käbi Laretei, and going until Daniel was about two years old. Bergman assures us that he has collected these images in an effort to continue developing his project of creating meaning through close-ups.

It's a very nice attempt to claim that his son's joyful expressions as a baby are, to Bergman, the most important inspiration of Bergman's life (he says this, in essentially so many words), though Bergman typically owned up to being a pretty lousy dad. And the footage itself is very nicely assembled, allowing Daniel's infant innocence slowly unfurl itself as we just follow in artlessly raw footage. Bergman was not an avant-garde director, notwithstanding the opening of Persona, but this feels a little bit like some of the avant-garde of the period in its attempt to aestheticise footage that was never meant to be aestheticised, and celebrating the purity of the human child. And also, regrettably, in its somewhat heavy use of voiceover near the end, as Bergman recites a somber poem that doesn't do much of anything to flesh out the meaning within the images. It's all part of the feeling that he knew he was the brand-name filmmaker involved, and wanted to live up to that; while I think there's definitely something bracing about the way the footage, Bergman, and the viewer end up in a kind of three-way dialogue, it's just a bit pushy and, I am almost tempted to say, arrogant. Again, he wasn't an avant-gardist, and a proper avant-gardist could surely have given him some good advice about letting the footage speak for itself.

"Birgit Nilsson"

Written and directed by Arne Arnbom

Incontestably the blandest segment. Arnbom is stimulated by the astonishing voice of international renowned Swedish opera singer Birgit Nilsson, and hey, so am I! And so we are presented with completely unadorned rehearsal and performance footage of a radio performance Nilsson gives with conductor Stig Westerberg. She's singing the climactic aria from Tristan und Isolde, one of her signature roles, no less. So I am 100% on board with the project of listening to this, and watching with fanboyish delight as Nilsson and Westerberg confer over their sheet music. But this is, like, not a movie. It's just footage being placed in front of our eyes, and occasionally being cut to an angle 90 degrees to the side, so we don't grow completely bored. But I was still pretty restless for this to do something, and I suspect I am a larger fan of Nilsson, and especially Nilsson singing Isolde, than anyone reading this, so if I was restless...

"Dygdens belöning" ["The Reward of Virtue"]

Adapted and directed by Hans Alfredson & Tage Danielsson

Based on the novel La femme vertueuse by Honoré de Balzac

An odd variant on everything else we've seen: the segment is kind of lousy, but the directors' introduction makes it worthwhile. Alfredson and Danielesson adopt a very haughty, superior tone, explaining that these little make-work projects are just not as exciting as bigger, better projects, but they found a good story by this German guy Balzen, or whatever, and they thought it might be good enough. I'm pretty sure it's a joke, but it's definitely a joke with a lot of biting truth to it, given the perfunctory feeling of many of these segments. And the segment that follows the introduction is treated as such a blow-off farce that I'm not clear how much of it is funny because it's bad on purpose, and how much of it is just them having very seriously told us that they didn't give a shit. It's a grating little snippet about a young woman (Lena Granhagen) who has been raped, and doesn't seem to be that worked up about it, but she still wants to see justice done, so she has to endure the patronising dismissal of a lawyer (Alfredson); the look of the thing is so flat and the comic tone so squawking and broad, one kind of hopes that it was being made deliberately as obnoxious as possible to underscore the meta-joke of the intro. But even if it's intentional, it's a tough thing to get right, and I don't know that this does.

"Smycket" ["The Necklace"]

Directed by Gustaf Molander

Adapted by Erland Josephson & Gustaf Molander

Based on the story "La Parure" by Guy de Maupassant

The big centerpiece, twice over: not only is Molander on-hand to grace the production with his presence, it's also the return to her native Sweden, after 28 years in Hollywood and elsewhere, of Ingrid Bergman, whose films with Molander in the 1930s were a crucial part of her budding career. The massive gulf between the production values of the other seven segments and this one is thus explained twice over, as well as everything else: the double length, the fact that this is a three-act narrative instead of just an anecdote, the fact that it's been stuck into this film despite not really addressing the question of stimulation.

"The Necklace" is a tale of the destruction that comes from desperately wanting to impress people who aren't worthy of being impressed, and running oneself into crushing poverty to do it. Mathilde Hartman (Bergman) is desperately sick of having to be poor, and live with no luxuries, only a just-getting-by level of not-quite-comfort. Her husband Paul (Gunnar Björnstrand) tolerates rather than sympathises with her complaints, but when a chance to attend a very fancy event comes up, he decides to go all-out, selling anything that isn't essential to buy a nice dress for the evening. To finish the look off, she borrows a necklace from her wealthy acquaintance Jeanette Ribbing (Gunnel Broström), and the two Hartmans have a wonderful night. Unfortunately, somewhere on the way home, Mathilde loses the necklace, and with the horrible, murderous pride of the lower-middle-class, the Hartmans decide to lie about this, and go into an unfathomable mountain of debt to buy a replacement without Jeanette finding out.

This is all pretty schematic, but it's so exquisitely-acted by Bergman and Björnstrand that it hardly matters. Molander's touch is light, and he lets the tone emerge from the actors' voices, rather than insisting upon it; the style is really almost neutral, for reasons that ultimately become clear in the segment's last scene, a nasty little nihilistic stab that the story doesn't really need; but who am I to correct Maupassant? Still, I can't help but feel that the segment, and Bergman's performance, would both be more satisfying without it.

"Negressen i skåpet" ["The Negress in the Closet"]

Written and directed by Vilgot Sjöman

Stimulantia doesn't end on its strongest segment - the opposite, in fact - but at least it ends on its god-damned weirdest. A man (Lars Ekborg) waits patiently till his wife (Inga Landgré) has left, at which point he opens the closet where he keeps an African woman (Glenna Forster-Jones). They fool around, and have a conversation about the formal nature of the film in which they're contained, and I am baffled by what to make any of it. It's doing far too much and too aggressively to just dismiss it, as much as it would be convenient to do so. Sjöman was a filmmaker with believed in the radical power of cinema, and I assume there's got to be some kind of commentary on colonialism and racism inside all of this, but that commentary is certainly not making itself very clear. Mostly, this just feels like a surrealistic sex comedy driven entirely by giddy editing that has been roughly contrasted with the shaggy naturalism of the opening scene, and built around a provocation that's so dumbfoundingly offensive on the surface that there has to be some kind of sardonic intent in using it. I imagine that I'm just too dumb to see it - I hope I'm too dumb to see it. The flipside is that the zany sexual slapstick and meta-cinematic word play all seem to point is directly towards thinking this is all wacky farce. And Sjöman's introduction is decidedly not looking to help us out. Anyway, even if it's "good", it would still be pretty annoyingly shrill in its wackiness, though I will pay "The Negress in the Closet" this compliment without hesitation: I guarantee that I'll be thinking more about this segment than the other seven-eighths of Stimulantia combined.

The film was pitched, apparently, by Bergman and TV producer/occasional director Arne Arnbom, which is fucking insane, given that their two segments are the ones with the strongest "*sigh* fine, I'll make a little short segment for your movie, I just happened to have this footage lying around" vibe in the whole picture. The concept is that several well-regarded directors in the Svensk Filmindustri sphere of influence were given one prompt - "what stimulates you?" - and around 10 or 12 minutes to answer that question (except for the penultimate segment, by the old master Gustaf Molander, who came out of retirement to make his sequence, and ended his career with this film; that was good enough reason to give him twice as much time as everyone else). Most of the segments are sincere enough, though most of them also feel like the directors wanted to get them over without too much fuss, and the whole movie has a general "good enough" vibe, which isn't enough to keep it afloat in the face of the couple of segments that are decisively less than good enough. But we'll get to those soon enough.

"Upptäckten" ["The Discovery"]

Written and directed by Hans Abramson

Notwithstanding all the things I just said, this actually must have taken Abramson some effort to put together. He acerbically notes that what "stimulates" him are sex and drugs, and he'd rather take the meaning loosely: what stimulates him is the memory of childhood, and specifically the childhood of Charlie Chaplin, who was himself inspired by childhood to become the filmmaker and movie star who charmed the world. And so Abramson's sequence is a documentary investigation into the place where Chaplin was born, on a street that no longer exists. As he pokes his camera around, inquiring of the locals if they know anything about the genius who arose from the place, Abramson's focus drifts: he starts to find what is vital and human in the neighborhood as it is presently constituted, not as it serves as the place where history took place. It's certainly a very sweet little piece, and it meanders in a way that feels very honest and inquisitive, but it ultimately just sort of lies there, harmlessly looking at the world and not doing anything else. The willingness to just let the world spill out in front of the camera is a good impulse, but the need to start by framing this as a Chaplin homage means that it can only spend literally a couple of minutes doing that; up to that point, it's just an unproductive fan tribute, and after that it simply has no time to accrue any weight. A pleasant way to start, but not anything else.

"Det var en gång två älskande..." ["Once Upon a Time There Were Two Lovers"]

Written and directed by Jörn Donner

Donner, like Abramson, begins by conceding that all stimulation is ultimately about sex; unlike Abramson, he does something with it, and the result is decisively my favorite thing here. Harriet Andersson and Sven-Bertil Taube play a couple about to have sex in a hotel room, but first, they go through an extensive routine of cleaning-up and prepping, with the unnamed "she" accidentally wounding the unnamed "he" in the process, but it's all in good flirty fun. The problem is that they get so involved in getting ready for sex that they wear themselves out without having sex.

That's cute and all, but the real strength of the segement lies in Donner's straight-faced comic tone. This is something like a what-if exercise in what realistic 1960s art house explorations of the human libido would look like if they were made like silent stag films, with some editing on loan from the '60s New Waves. It's punchy and even, dare I say it, a little zany, benefiting enormously from Andersson and Taube's chemistry and willingness to dive headfirst into the silliness without self-consciousness, or without sacrificing the sexy charge of the material. It's very light and playful, and formally inventive enough to feel like Donner was thinking a bit harder than anyone else here about the possibilities of the Stimulantia project, not just its limitations.

"Konfrontationer" ["Confrontations"]

Written and directed by Lars Görling

Görling's introduction (these films all start with introductions by the director) spends a whole lot of time feeling his way through linguistic philosophy, name-dropping Wittgenstein, all to explain why it's going to be such a very weird collage of ideas and images he's about to drop on us, at which point we are treated to: a montage of stills and moving images about formula racing. And the profundities don't stop here, either: Görling continues to muse about the appeal of racing, the death-drive of it, the power and eroticism of the care rattling one's body, and so on. And it's, like a lot to try to pack onto these images, though i think there's at least a possibility that it's tongue-in-cheek. The montage itself is extremely well-done, and the abstract poetry of the racing, as assembled through these piecemeal images and fragments of moments, feels like it's getting at the expression deeper than words that Görling seems to be talking about. But it would, frankly, have gotten there more beautifully and convincingly without him prattling.

"Daniel"

Written and directed by Ingmar Bergman

Speaking of pretentiously loading up one's delicate little visual collage with portentous verbiage: Bergman is clearly aware that he's Famous International Art Director Ingmar Bergman, and so he packs some real grave weight into his introduction, telling us that we're about to see the curated images of his eighth child (of nine) and lastborn son, Daniel Sebastian Bergman, filmed between the pregnancy of his mother, Bergman's fourth wife, Käbi Laretei, and going until Daniel was about two years old. Bergman assures us that he has collected these images in an effort to continue developing his project of creating meaning through close-ups.

It's a very nice attempt to claim that his son's joyful expressions as a baby are, to Bergman, the most important inspiration of Bergman's life (he says this, in essentially so many words), though Bergman typically owned up to being a pretty lousy dad. And the footage itself is very nicely assembled, allowing Daniel's infant innocence slowly unfurl itself as we just follow in artlessly raw footage. Bergman was not an avant-garde director, notwithstanding the opening of Persona, but this feels a little bit like some of the avant-garde of the period in its attempt to aestheticise footage that was never meant to be aestheticised, and celebrating the purity of the human child. And also, regrettably, in its somewhat heavy use of voiceover near the end, as Bergman recites a somber poem that doesn't do much of anything to flesh out the meaning within the images. It's all part of the feeling that he knew he was the brand-name filmmaker involved, and wanted to live up to that; while I think there's definitely something bracing about the way the footage, Bergman, and the viewer end up in a kind of three-way dialogue, it's just a bit pushy and, I am almost tempted to say, arrogant. Again, he wasn't an avant-gardist, and a proper avant-gardist could surely have given him some good advice about letting the footage speak for itself.

"Birgit Nilsson"

Written and directed by Arne Arnbom

Incontestably the blandest segment. Arnbom is stimulated by the astonishing voice of international renowned Swedish opera singer Birgit Nilsson, and hey, so am I! And so we are presented with completely unadorned rehearsal and performance footage of a radio performance Nilsson gives with conductor Stig Westerberg. She's singing the climactic aria from Tristan und Isolde, one of her signature roles, no less. So I am 100% on board with the project of listening to this, and watching with fanboyish delight as Nilsson and Westerberg confer over their sheet music. But this is, like, not a movie. It's just footage being placed in front of our eyes, and occasionally being cut to an angle 90 degrees to the side, so we don't grow completely bored. But I was still pretty restless for this to do something, and I suspect I am a larger fan of Nilsson, and especially Nilsson singing Isolde, than anyone reading this, so if I was restless...

"Dygdens belöning" ["The Reward of Virtue"]

Adapted and directed by Hans Alfredson & Tage Danielsson

Based on the novel La femme vertueuse by Honoré de Balzac

An odd variant on everything else we've seen: the segment is kind of lousy, but the directors' introduction makes it worthwhile. Alfredson and Danielesson adopt a very haughty, superior tone, explaining that these little make-work projects are just not as exciting as bigger, better projects, but they found a good story by this German guy Balzen, or whatever, and they thought it might be good enough. I'm pretty sure it's a joke, but it's definitely a joke with a lot of biting truth to it, given the perfunctory feeling of many of these segments. And the segment that follows the introduction is treated as such a blow-off farce that I'm not clear how much of it is funny because it's bad on purpose, and how much of it is just them having very seriously told us that they didn't give a shit. It's a grating little snippet about a young woman (Lena Granhagen) who has been raped, and doesn't seem to be that worked up about it, but she still wants to see justice done, so she has to endure the patronising dismissal of a lawyer (Alfredson); the look of the thing is so flat and the comic tone so squawking and broad, one kind of hopes that it was being made deliberately as obnoxious as possible to underscore the meta-joke of the intro. But even if it's intentional, it's a tough thing to get right, and I don't know that this does.

"Smycket" ["The Necklace"]

Directed by Gustaf Molander

Adapted by Erland Josephson & Gustaf Molander

Based on the story "La Parure" by Guy de Maupassant

The big centerpiece, twice over: not only is Molander on-hand to grace the production with his presence, it's also the return to her native Sweden, after 28 years in Hollywood and elsewhere, of Ingrid Bergman, whose films with Molander in the 1930s were a crucial part of her budding career. The massive gulf between the production values of the other seven segments and this one is thus explained twice over, as well as everything else: the double length, the fact that this is a three-act narrative instead of just an anecdote, the fact that it's been stuck into this film despite not really addressing the question of stimulation.

"The Necklace" is a tale of the destruction that comes from desperately wanting to impress people who aren't worthy of being impressed, and running oneself into crushing poverty to do it. Mathilde Hartman (Bergman) is desperately sick of having to be poor, and live with no luxuries, only a just-getting-by level of not-quite-comfort. Her husband Paul (Gunnar Björnstrand) tolerates rather than sympathises with her complaints, but when a chance to attend a very fancy event comes up, he decides to go all-out, selling anything that isn't essential to buy a nice dress for the evening. To finish the look off, she borrows a necklace from her wealthy acquaintance Jeanette Ribbing (Gunnel Broström), and the two Hartmans have a wonderful night. Unfortunately, somewhere on the way home, Mathilde loses the necklace, and with the horrible, murderous pride of the lower-middle-class, the Hartmans decide to lie about this, and go into an unfathomable mountain of debt to buy a replacement without Jeanette finding out.

This is all pretty schematic, but it's so exquisitely-acted by Bergman and Björnstrand that it hardly matters. Molander's touch is light, and he lets the tone emerge from the actors' voices, rather than insisting upon it; the style is really almost neutral, for reasons that ultimately become clear in the segment's last scene, a nasty little nihilistic stab that the story doesn't really need; but who am I to correct Maupassant? Still, I can't help but feel that the segment, and Bergman's performance, would both be more satisfying without it.

"Negressen i skåpet" ["The Negress in the Closet"]

Written and directed by Vilgot Sjöman

Stimulantia doesn't end on its strongest segment - the opposite, in fact - but at least it ends on its god-damned weirdest. A man (Lars Ekborg) waits patiently till his wife (Inga Landgré) has left, at which point he opens the closet where he keeps an African woman (Glenna Forster-Jones). They fool around, and have a conversation about the formal nature of the film in which they're contained, and I am baffled by what to make any of it. It's doing far too much and too aggressively to just dismiss it, as much as it would be convenient to do so. Sjöman was a filmmaker with believed in the radical power of cinema, and I assume there's got to be some kind of commentary on colonialism and racism inside all of this, but that commentary is certainly not making itself very clear. Mostly, this just feels like a surrealistic sex comedy driven entirely by giddy editing that has been roughly contrasted with the shaggy naturalism of the opening scene, and built around a provocation that's so dumbfoundingly offensive on the surface that there has to be some kind of sardonic intent in using it. I imagine that I'm just too dumb to see it - I hope I'm too dumb to see it. The flipside is that the zany sexual slapstick and meta-cinematic word play all seem to point is directly towards thinking this is all wacky farce. And Sjöman's introduction is decidedly not looking to help us out. Anyway, even if it's "good", it would still be pretty annoyingly shrill in its wackiness, though I will pay "The Negress in the Closet" this compliment without hesitation: I guarantee that I'll be thinking more about this segment than the other seven-eighths of Stimulantia combined.