Cello, goodbye

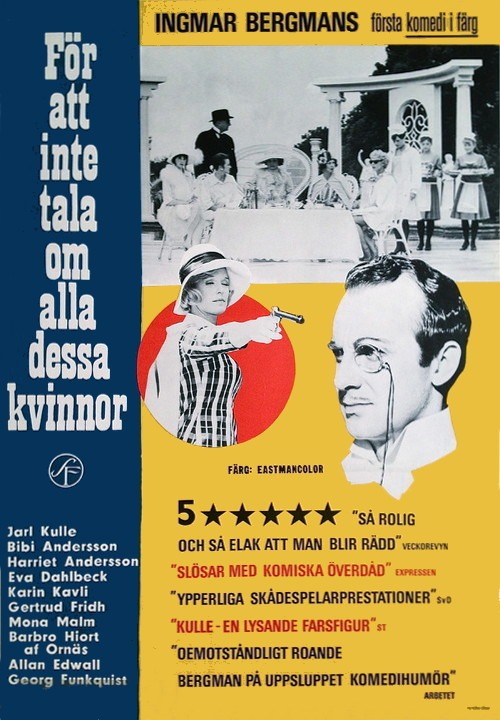

Between 1960 and 1963, Ingmar Bergman directed five feature films, and four of them were the most intensely depressing work of his career as it then stood. In particular, the one-two punch of 1963's Winter Light and The Silence, a pair of films in which he dove headfirst into watching the degree to which human beings could suffer in a universe devoid of meaning, God, or love between people. They are two of the bleakest films of the 1960s, and as had happened before when Bergman turned in something that desperately unpleasant, Svensk Filmindustri asked if he might be willing to make something actually watchable for his next film. The result, coming out in 1964, was All These Women (first released in English as Now About These Women, a slightly more mellifluous translation of the original Not to Mention These Women, the last of which is of course the best), a zany cartoon farce that Bergman co-wrote with his frequent acting collaborator, Erland Josephson. It was their second script together, and the first they signed under their own names (they had previously written the 1961 bomb The Pleasure Garden as "Buntel Ericsson"), and the film's failure ensured they never wrote a third.

Cinema history has not missed out on a fertile collaboration, to be blunt about it. All These Women has strengths that its outraged detractors back in the '60s might have missed (it was dismissed in Sweden and greeted with hissing hostility everywhere else, though Sight & Sound had some kind things to say, and apparently the French mostly thought it was fine), but those strengths do not inhere in the screenplay. The story is a weird, episodic whirlwind: in what's apparently the 1920s, Cornelius (Jarl Kulle), a critic and historian, arrives at the home of the great (and never seen, or at least only seen elliptically) cellist Felix, whose biography he's writing. Felix proves to be unavailable and elusive, so Cornelius spends the next four days wandering the great artist's villa, which is currently populated by seven women who have all been his lovers at some point. Figuring that this will at least be a way to get some good gossip, Cornelius speaks to each of them, occasionally putting in a bit to a sexual assignation of his own, and less occasionally succeeding. Eventually, he is able to blackmail Felix into playing his own composition for cello and piano, the critic bullying the artist into making art to order.

This little slip of a story is brought to life in a wild mixture of comic modes: the beating heart, to which it always returns, is farce, but it takes time for swerves into '20s style slapstick comedy (with one scene actually filmed without sync sound), and midcentury cartoon anarchy - Cornelius is, at a certain point, blown up with firecrackers, and is next seen covered head to toe in black soot. Plus, the whole thing is both a broad, genial parody of Federico Fellini (in particular 8½, supposedly, though what I got was mostly the general vibe of grotesque carnival. If Juliet of the Spirits had already come out, that's where my mind would have gone first), and a specific, pointed satire of effete critics. And because this is a Bergman film, even if it's a pretty bizarre one that does very nearly none of the things his other movies did, even his dips into farce, there's some difficult and troubling autocritique, with Felix obviously standing in for the director, his social anxiety, his haughty perfectionism, and his fixation on collecting women whom he sincerely, albeit insufficiently, loves. This is definitely the least of the film's identities, but it's there.

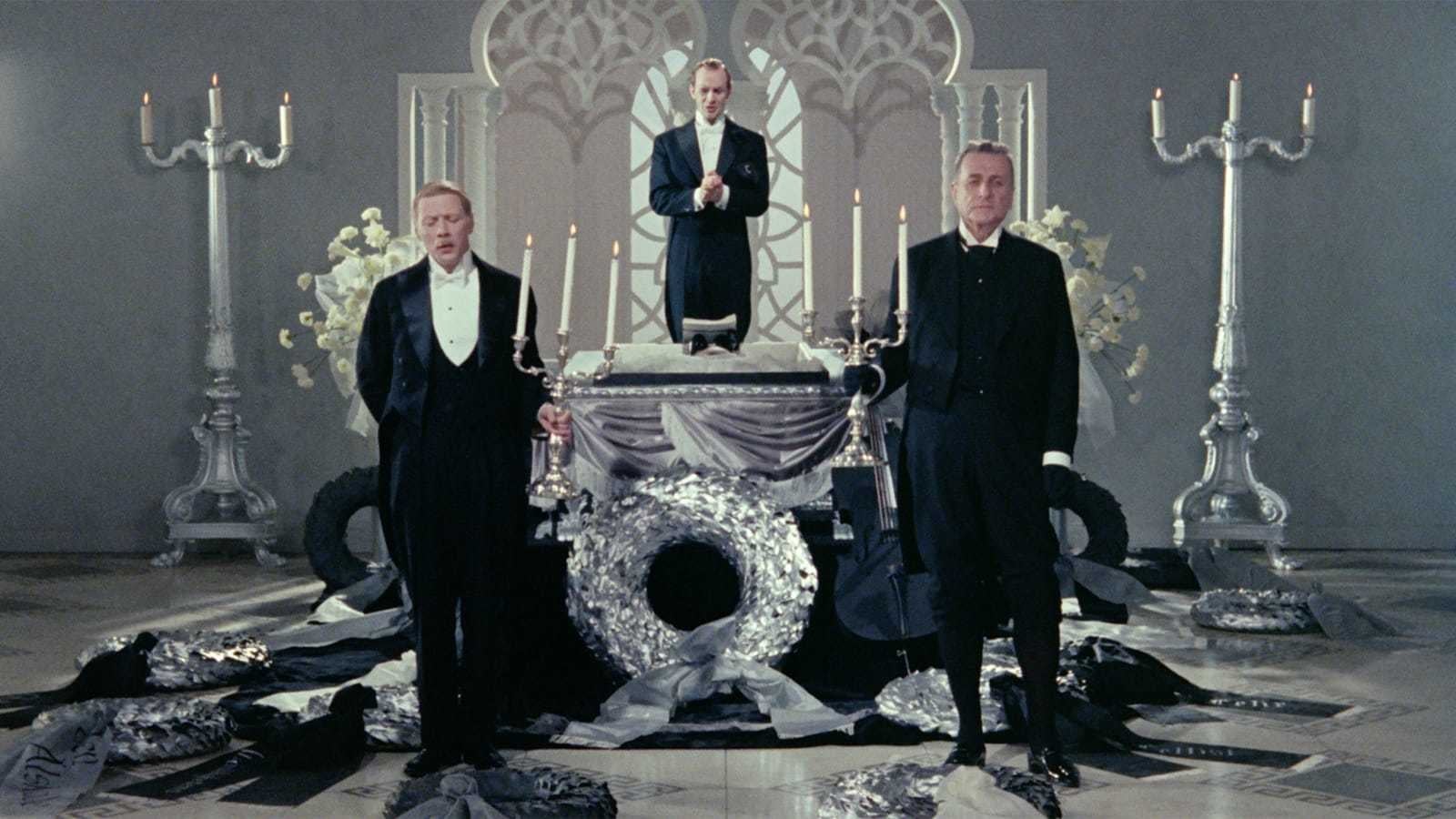

What's there much more, though, is that manic montage of different comic types, and it's... whew. Bergman could do comedy, let us absolutely not repeat that lazy canard. A Lesson in Love in 1954, and Smiles of a Summer Night in 1955, and The Devil's Eye in 1960 all comfortably demonstrate that he could do comedy pretty damn well, in fact. But what those films all share is a very definite sense of humor: they are dry, urbane comedies for the most part, wry and stately and full of elegant theatricality. Given what a grab bag All These Women is, there's of course some of that in there: there almost has to be. But what it is mostly is, is pretty gosh-darn wacky. The silent slapstick and Looney Tunes vibe is not one that's elegant in the slightest, theatrically or otherwise; indeed, there's a fleshy grubbiness here, and the thing is, Bergman is just not a grubby filmmaker, even when he's a fleshy one. And the comic mode he's trying for seems to have severely outstripped his ability to control it. When the film is actually funny - as it is multiple times - it's always because it's retrenched farthest into arch sarcasm, as in the opening scene, which actually place near the end of the story: it's a several-minutes long wide shot of Felix's wake, with two extremely prim footmen standing at the base of his funereal while his seven women walk by to offer their grandiose, stately performance of morning. And the entire set is production-designed in black-and-white - this was Bergman's first film in color, you see, and I refuse to believe other than that starting with a marathon-length take of a monochromatic funeral was a sly piss-take on what "Bergman makes a color comedy" would look like. But even without the meta-humor, it's one of the most genuinely funny parts of the film, with the only real competition being a series of close-ups on a gun, with the open question of whether Felix's actual, official wife Adelaide (Eva Dahlbeck) is going to kill him. So, again: loud zaniness isn't the mode that works best here.

Indeed, I am severely tempted to say it doesn't work at all. Bergman strains to find an accommodation for that comic mood in his severely aestheticised approach to the material, and Kulle (whether encouraged by the director or not, I cannot say) is just shamelessly big and broad, flailing about with swooning campy excess, though it is extremely unclear to me that it is remotely intentional for it to be campy. Between the two of them, every one of Cornelius's gags is heavily underlined and indicated, in a way that devours any chance of it also being funny; the film is loudly and messily screeching at us, "that was a joke! Did you laugh?! May I explain it?!" Everything Bergman is ever funny, it's because of innuendo and understatment. All These Women is an exercise in pure, droning overstatement.

The episodic plotting strands its supporting cast, several of whom have demonstrated comic gifts. The only performers who get to stand out at all are Dahlbeck, Karin Kavli as the elderly and imperious Madame Tussaud, and Harriett Andersson as the saucy maid Isolde; the former two have the benefit of the only roles that are actually written in a particularly distinctive way, while Andersson benefits from a part that couldn't be more lazily tailored to her exact screen presence. I do not by any means intend to accuse her of laziness, it's entirely on Bergman and maybe Josephson; the role demands nothing of her and she gives it only slightly more than nothing, but she perpetually manages to pull focus no matter what's happening in the shot, and she is unsurprisingly the cast member who's best at shooting a bolt of insouciant sexuality into this alleged sex comedy (the first shot specifically designed to make sure we've noticed her finds her unselfconsciously adjusting her decolletage, for example). Meanwhile, Bibi Andersson, Gertrud Fridh, Mona Malm, and Barbro Hiort af Ornäs are all doing their best with small roles that have no significant personality, only "types", and there's not even a lot of variation in those types.

The point being, the script gives none of these seven women anything much to work with, while the directing keeps allowing Kulle to mug and squawk and make a nuisance of himself and generally suck all the air out of scenes. It feels like a pretty shabby trick on all of them, and it's a miserable shame that this was Bergman's last film with Dahlbeck ever, and his last film with Harriet Andersson for eight years; it's not a good send-off for either of those great collaborations (thankfully, he would manage to make things up to Bibi Andersson almost immediately). One could of course talk about the vague melancholia, the satiric elements, the implications of framing this all as an elaborate takedown of critics, who through Cornelius are subjected to every humiliation on the books - I don't really want to, but one could. All of this still feels like an asterisk against the fact that this is a big wacky comedy and it's just not very funny: loud, hectic, dizzying, but not funny. It's pretty much like a lot of other '60s sex comedies, in fact, the ones made alongside the British New Wave (or as part of it) that mistake being sloppy and action-packed for being good.

The other thing one can talk about, and I'll force myself to, is the fact that we do, in fact, find ourselves with Bergman's very first color film. And his last, for a long time: the experience killed his enthusiasm for the medium and he wouldn't willingly return to color until 1972 (though the demands of the commercial marketplace meant that a couple of his films prior to then were in color). It is, at least, a very clear experiment in color, not just a reflexive use of the medium because that's what you do; he and cinematographer Sven Nykvist put a lot of energy into doing very weird things with the Eastmancolor stock they were using. And that's above and beyond the weirdness of P.A. Lundgren's desaturated production design and Mago's bold red and black costumes. The film has a bleached, washed-out look, one that plainly took real effort to achieve: it's kind of ugly as hell, but in a purposeful, complicated way. Nykvist later claimed that it was over-lit, and he's not wrong; there's a glowing softness that is one of the most notably odd and ugly things about the film. But it's definitely different, creating a kind of faded fairy-tale glamor. It is a film made up out of desiccated pastels, and spaces washed with a bluish-grey, and the whole thing has a very unmistakable feeling of dreamy rot. Does this look actually do anything for the film? Maybe if the film was working well enough to take advantage of the aesthetic, it would. As it is, the color at least makes for something to think about that feels purposeful and striking, and given the messiness of the film's comedy, I'll take purposeful weirdness if I can't get something better.

Cinema history has not missed out on a fertile collaboration, to be blunt about it. All These Women has strengths that its outraged detractors back in the '60s might have missed (it was dismissed in Sweden and greeted with hissing hostility everywhere else, though Sight & Sound had some kind things to say, and apparently the French mostly thought it was fine), but those strengths do not inhere in the screenplay. The story is a weird, episodic whirlwind: in what's apparently the 1920s, Cornelius (Jarl Kulle), a critic and historian, arrives at the home of the great (and never seen, or at least only seen elliptically) cellist Felix, whose biography he's writing. Felix proves to be unavailable and elusive, so Cornelius spends the next four days wandering the great artist's villa, which is currently populated by seven women who have all been his lovers at some point. Figuring that this will at least be a way to get some good gossip, Cornelius speaks to each of them, occasionally putting in a bit to a sexual assignation of his own, and less occasionally succeeding. Eventually, he is able to blackmail Felix into playing his own composition for cello and piano, the critic bullying the artist into making art to order.

This little slip of a story is brought to life in a wild mixture of comic modes: the beating heart, to which it always returns, is farce, but it takes time for swerves into '20s style slapstick comedy (with one scene actually filmed without sync sound), and midcentury cartoon anarchy - Cornelius is, at a certain point, blown up with firecrackers, and is next seen covered head to toe in black soot. Plus, the whole thing is both a broad, genial parody of Federico Fellini (in particular 8½, supposedly, though what I got was mostly the general vibe of grotesque carnival. If Juliet of the Spirits had already come out, that's where my mind would have gone first), and a specific, pointed satire of effete critics. And because this is a Bergman film, even if it's a pretty bizarre one that does very nearly none of the things his other movies did, even his dips into farce, there's some difficult and troubling autocritique, with Felix obviously standing in for the director, his social anxiety, his haughty perfectionism, and his fixation on collecting women whom he sincerely, albeit insufficiently, loves. This is definitely the least of the film's identities, but it's there.

What's there much more, though, is that manic montage of different comic types, and it's... whew. Bergman could do comedy, let us absolutely not repeat that lazy canard. A Lesson in Love in 1954, and Smiles of a Summer Night in 1955, and The Devil's Eye in 1960 all comfortably demonstrate that he could do comedy pretty damn well, in fact. But what those films all share is a very definite sense of humor: they are dry, urbane comedies for the most part, wry and stately and full of elegant theatricality. Given what a grab bag All These Women is, there's of course some of that in there: there almost has to be. But what it is mostly is, is pretty gosh-darn wacky. The silent slapstick and Looney Tunes vibe is not one that's elegant in the slightest, theatrically or otherwise; indeed, there's a fleshy grubbiness here, and the thing is, Bergman is just not a grubby filmmaker, even when he's a fleshy one. And the comic mode he's trying for seems to have severely outstripped his ability to control it. When the film is actually funny - as it is multiple times - it's always because it's retrenched farthest into arch sarcasm, as in the opening scene, which actually place near the end of the story: it's a several-minutes long wide shot of Felix's wake, with two extremely prim footmen standing at the base of his funereal while his seven women walk by to offer their grandiose, stately performance of morning. And the entire set is production-designed in black-and-white - this was Bergman's first film in color, you see, and I refuse to believe other than that starting with a marathon-length take of a monochromatic funeral was a sly piss-take on what "Bergman makes a color comedy" would look like. But even without the meta-humor, it's one of the most genuinely funny parts of the film, with the only real competition being a series of close-ups on a gun, with the open question of whether Felix's actual, official wife Adelaide (Eva Dahlbeck) is going to kill him. So, again: loud zaniness isn't the mode that works best here.

Indeed, I am severely tempted to say it doesn't work at all. Bergman strains to find an accommodation for that comic mood in his severely aestheticised approach to the material, and Kulle (whether encouraged by the director or not, I cannot say) is just shamelessly big and broad, flailing about with swooning campy excess, though it is extremely unclear to me that it is remotely intentional for it to be campy. Between the two of them, every one of Cornelius's gags is heavily underlined and indicated, in a way that devours any chance of it also being funny; the film is loudly and messily screeching at us, "that was a joke! Did you laugh?! May I explain it?!" Everything Bergman is ever funny, it's because of innuendo and understatment. All These Women is an exercise in pure, droning overstatement.

The episodic plotting strands its supporting cast, several of whom have demonstrated comic gifts. The only performers who get to stand out at all are Dahlbeck, Karin Kavli as the elderly and imperious Madame Tussaud, and Harriett Andersson as the saucy maid Isolde; the former two have the benefit of the only roles that are actually written in a particularly distinctive way, while Andersson benefits from a part that couldn't be more lazily tailored to her exact screen presence. I do not by any means intend to accuse her of laziness, it's entirely on Bergman and maybe Josephson; the role demands nothing of her and she gives it only slightly more than nothing, but she perpetually manages to pull focus no matter what's happening in the shot, and she is unsurprisingly the cast member who's best at shooting a bolt of insouciant sexuality into this alleged sex comedy (the first shot specifically designed to make sure we've noticed her finds her unselfconsciously adjusting her decolletage, for example). Meanwhile, Bibi Andersson, Gertrud Fridh, Mona Malm, and Barbro Hiort af Ornäs are all doing their best with small roles that have no significant personality, only "types", and there's not even a lot of variation in those types.

The point being, the script gives none of these seven women anything much to work with, while the directing keeps allowing Kulle to mug and squawk and make a nuisance of himself and generally suck all the air out of scenes. It feels like a pretty shabby trick on all of them, and it's a miserable shame that this was Bergman's last film with Dahlbeck ever, and his last film with Harriet Andersson for eight years; it's not a good send-off for either of those great collaborations (thankfully, he would manage to make things up to Bibi Andersson almost immediately). One could of course talk about the vague melancholia, the satiric elements, the implications of framing this all as an elaborate takedown of critics, who through Cornelius are subjected to every humiliation on the books - I don't really want to, but one could. All of this still feels like an asterisk against the fact that this is a big wacky comedy and it's just not very funny: loud, hectic, dizzying, but not funny. It's pretty much like a lot of other '60s sex comedies, in fact, the ones made alongside the British New Wave (or as part of it) that mistake being sloppy and action-packed for being good.

The other thing one can talk about, and I'll force myself to, is the fact that we do, in fact, find ourselves with Bergman's very first color film. And his last, for a long time: the experience killed his enthusiasm for the medium and he wouldn't willingly return to color until 1972 (though the demands of the commercial marketplace meant that a couple of his films prior to then were in color). It is, at least, a very clear experiment in color, not just a reflexive use of the medium because that's what you do; he and cinematographer Sven Nykvist put a lot of energy into doing very weird things with the Eastmancolor stock they were using. And that's above and beyond the weirdness of P.A. Lundgren's desaturated production design and Mago's bold red and black costumes. The film has a bleached, washed-out look, one that plainly took real effort to achieve: it's kind of ugly as hell, but in a purposeful, complicated way. Nykvist later claimed that it was over-lit, and he's not wrong; there's a glowing softness that is one of the most notably odd and ugly things about the film. But it's definitely different, creating a kind of faded fairy-tale glamor. It is a film made up out of desiccated pastels, and spaces washed with a bluish-grey, and the whole thing has a very unmistakable feeling of dreamy rot. Does this look actually do anything for the film? Maybe if the film was working well enough to take advantage of the aesthetic, it would. As it is, the color at least makes for something to think about that feels purposeful and striking, and given the messiness of the film's comedy, I'll take purposeful weirdness if I can't get something better.

Categories: comedies, farce, ingmar bergman, scandinavian cinema, unfunny comedies