Don't have a cow

Kelly Reichardt has never felt like a director who was forcing her career to go in a certain direction, or build to any kind of definitive statement. Her first six features, dating back to 1994's River of Grass, share a good number of characteristics, but one of the most important is that they're resolutely small and shambling; the focus is on characters in moments of their life where nothing much is happening (she even managed to bring this feeling to a story about eco-terrorists blowing up a dam in the 2013 Night Moves). They are casual, drifting movies, building up to inconclusiveness shrugs, not grand overarching statements combining to articulate a worldview.

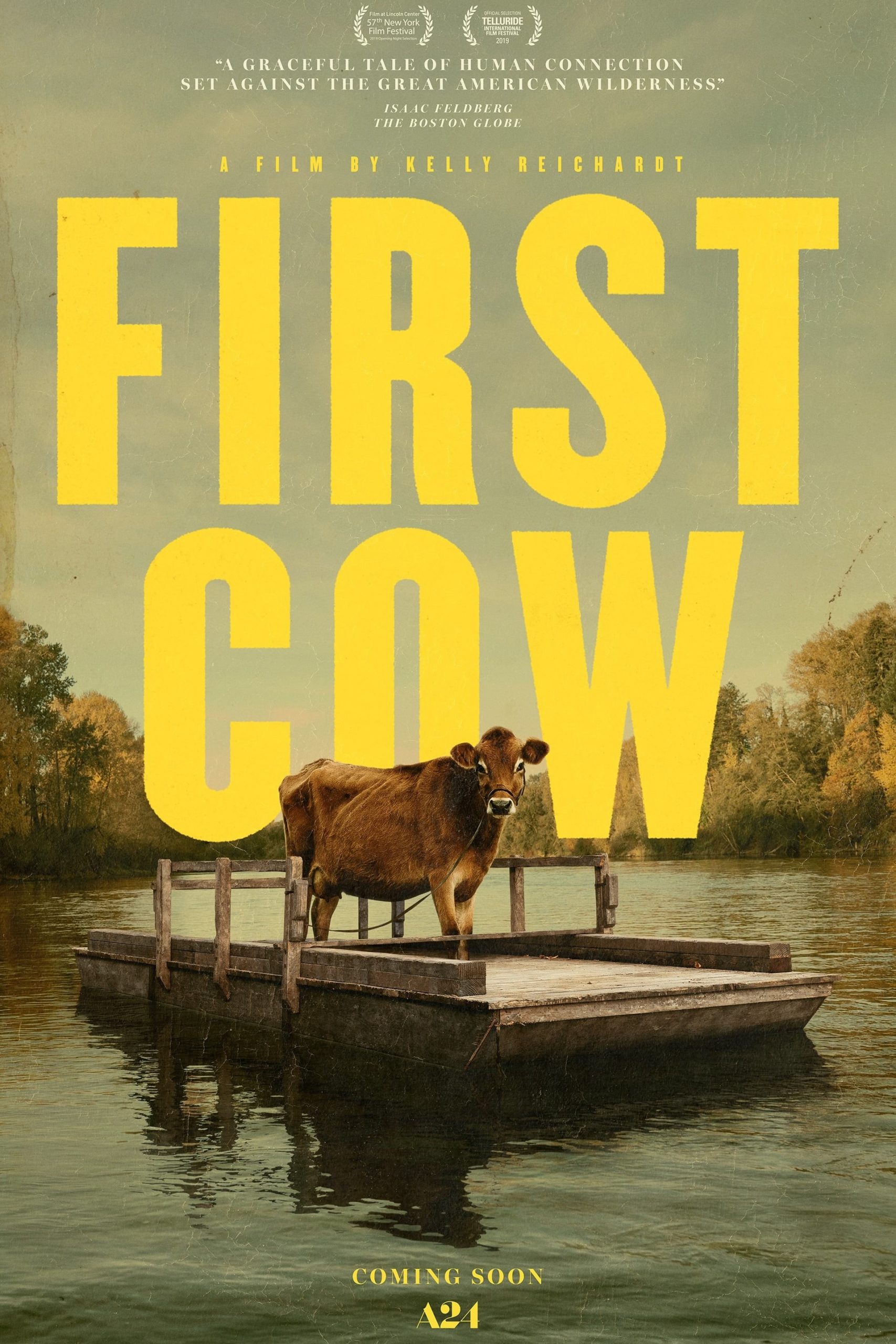

This is all, of course, prefatory to declaring that Reichardt had a definitive statement after all, and it has come in the form of First Cow, which somehow manages to be a grand historical epic about the history of the United States as well as a substantially plotless, quietly intimate story about two men who don't talk very much but bond over their shared outsider status in a relatively small patch of forest. "Intimate story about two men who don't talk very much" starts pointing us to one of the ways in which First Cow is sort of the Reichardt-est of Reichardt films: it feels very much like a summing-up of elements from all her previous work. A pair of minimally-articulate men also featured as the focal point of her 2006 sophomore feature and critical breakthrough, Old Joy, which is still maybe the single purest distillation of Reichardt's miniaturist style and obsession with finding psychological depths in performances that seem to glide across the surface of the characters. First Cow is the mirror image of Old Joy; that film was about an old friendship slowly and gently unraveling, while this film is about a new friendship forming. But they are plainly in dialogue with each other, right down to how they both create a subterranean homoerotic charge in the imagery and blocking that isn't present in the writing and maybe not even in the acting.

First Cow is set in the Oregon Country in the west of the North American continent, sometime in the first half of the 19th Century, a bit earlier than the events of Reichardt's 2010 Western Meek's Cutoff, the other one of her films that's being most actively referred back to. "Cookie" Figowitz (John Magaro) is part of a fur trapping team penetrating the wilderness, but he's openly derided by the trappers as insufficiently masculine - they don't put it in those terms, but that's clearly the thrust of it. During the journey, he crosses paths with the fugitive Chinese immigrant King-Lu (Orion Lee), whom he helps hide and later escape. Later, Cookie leaves the trappers to try establishing himself in the rickety frontier town outside a fort that appears to be the solitary establishment of any human government in the area, and after aimlessly wandering for a bit, runs into King-Lu again. They bond some more, and end up forming a partnership, going into business selling biscuits. And the biscuits finally bring the cow into the picture: the first and only one in the region, she's the property of Factor (Toby Jones), a wealthy, clueless Englishman, and Cookie and King-Lu sneak onto his land every night to milk her.

That gets us to some of the things the movie has on its mind - friendship, being a social outcast for reasons of identity, behavior, or both, the ways in which the deeply immiserated find strategies for functioning on the margins of the world, making little communitarian bubbles for themselves in the face of primitive capitalism. First Cow is a thoughtful, rich film of themes presented unmistakably, but without urgency: they're there for us to pick up and think through at our leisure. It is, in one light, about how the thing called the United States fashioned itself both by imposing itself on the land and being forced to adjust to it, and how systems of exploitation simply appear, fully-formed, without any specific choice made by malicious actors. It affords itself a sentimental streak; in one scene, a Chinese immigrant greets an indigenous native in a Yiddishism, a sweet little tribute to the idea of America as a melting pot. Elsewhere, it glares with bitter, cynical humor at Factor's blithe way of effortlessly steamrolling over the world. It is most decidedly not interested in didacticism, in any direction; it's presenting a broad, all-encompassing portrait of the things that go into "America", which is maybe the thing that Westerns are best at out of all the genres, and Reichardt and her longtime co-writer Jon Raymond (adapting his novel "The Half-Life") do a fantastic job of drawing from the mythic scope of the genre while pinning it down to something specific and unromantic. This is already present right at the start: the film actually opens in the present day, or something like it, on a shot of an ore freighter gradually cutting its way across the exact middle of the frame, and from here a woman (Alia Shawkat) walking her dog in the woods is stunned to find a pair of old skeletons poking out of the dirt. It's a little bit of not much, lingered over at some length while nothing happens but a slow delivery of B-roll, but it immediately contextualises this as a dive into history: Cookie and King-Lu are separated from us by one level of narration, and that level is where film does all of its work of historical commentary and anti-myth.

At the same time, the specific line between present and past is deliberately blurry; the cut between the two happens in the middle of shots of nature, and our only cue that things have changed is that William Tyler's superb score has started its light chiming on the soundtrack. And this is my much less graceful and invisible attempt to transition into another important thing about First Cow, which is that as much as its themes are dense and interesting, they're really not where the film lives. One of Reichardt's greatest strengths lies in her ability to sink into the vibe of a place, and she and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt (collaborating for the fourth time) are doing especially good work in that direction here. First Cow was shot in the boxy, old-fashioned 1.33:1 aspect ratio (as was Meek's Cutoff, Reichardt and Blauvelt's first collaboration), and the film serves as a gorgeous reminder of how well that aspect ratio serves to neatly package human bodies while giving us enough space around them to get a sense of how they're situated in an environment. The geometry of the compositions is never as merciless in pinning the characters as it was in Meek's Cutoff; rather, it situates them, surrounds them. Since Meek's Cutoff is about anxiety in a hostile landscape, while First Cow is about finding a comfortable and nourishing place to live, this emphasis feels just right.

Really, though, the main thing about the movie is just that it lets us and the characters move through it steadily and slowly. It is, at 122 minutes, Reichardt's longest production to date, and it uses that time immaculately well, given that its goal is as much the creation of an aura as it is the recounting of a story, maybe more. Right from its unhurried, more-curious-than-shocked look at the woman finding the skeletons, First Cow wants us to think about these woods of Oregon, past and present. It wants us to think about moving through them, living in them, slowly finding a space in them that feels right. Pure Kelly Reichardt stuff, the same thing we see in all her films, but stately and grander and more confident.

And populated by two exceptionally fine human specimens. In a career overwhelmingly well-supplied with strong characters expressed subtly and elliptically, Cookie and King-Lu still stand out for the simple precision with which the writers sketch them out and the actor soak in them. The fact that the film pivots around one such deep, powerful, and I daresay universal emotional experience - the joy of getting to know somebody new who moves through the world on your exact wavelength - works beautifully with the spare simplicity of the filmmaking: it is a delicate way of teasing out and showcasing an emotion that is, as such things go, very small, while also being very wonderful and warm. There's more to the film than that - Reichardt isn't about to start making fuzzy movies now, and the film's cool depiction of all the ways that power hierarchies can manifest and work their cruelty certainly takes up much of its running time. But that simple kind feeling is definitely a part of it, and it's a kind of warmth that hardly ever shows up in movies, a medium not especially comfortable with depicting friendship. All told, it's a rewarding sprawl of history, emotions, and environments, and while I'm not ready to call it the director's best film yet... well, I did just use the word "yet", didn't I.

This is all, of course, prefatory to declaring that Reichardt had a definitive statement after all, and it has come in the form of First Cow, which somehow manages to be a grand historical epic about the history of the United States as well as a substantially plotless, quietly intimate story about two men who don't talk very much but bond over their shared outsider status in a relatively small patch of forest. "Intimate story about two men who don't talk very much" starts pointing us to one of the ways in which First Cow is sort of the Reichardt-est of Reichardt films: it feels very much like a summing-up of elements from all her previous work. A pair of minimally-articulate men also featured as the focal point of her 2006 sophomore feature and critical breakthrough, Old Joy, which is still maybe the single purest distillation of Reichardt's miniaturist style and obsession with finding psychological depths in performances that seem to glide across the surface of the characters. First Cow is the mirror image of Old Joy; that film was about an old friendship slowly and gently unraveling, while this film is about a new friendship forming. But they are plainly in dialogue with each other, right down to how they both create a subterranean homoerotic charge in the imagery and blocking that isn't present in the writing and maybe not even in the acting.

First Cow is set in the Oregon Country in the west of the North American continent, sometime in the first half of the 19th Century, a bit earlier than the events of Reichardt's 2010 Western Meek's Cutoff, the other one of her films that's being most actively referred back to. "Cookie" Figowitz (John Magaro) is part of a fur trapping team penetrating the wilderness, but he's openly derided by the trappers as insufficiently masculine - they don't put it in those terms, but that's clearly the thrust of it. During the journey, he crosses paths with the fugitive Chinese immigrant King-Lu (Orion Lee), whom he helps hide and later escape. Later, Cookie leaves the trappers to try establishing himself in the rickety frontier town outside a fort that appears to be the solitary establishment of any human government in the area, and after aimlessly wandering for a bit, runs into King-Lu again. They bond some more, and end up forming a partnership, going into business selling biscuits. And the biscuits finally bring the cow into the picture: the first and only one in the region, she's the property of Factor (Toby Jones), a wealthy, clueless Englishman, and Cookie and King-Lu sneak onto his land every night to milk her.

That gets us to some of the things the movie has on its mind - friendship, being a social outcast for reasons of identity, behavior, or both, the ways in which the deeply immiserated find strategies for functioning on the margins of the world, making little communitarian bubbles for themselves in the face of primitive capitalism. First Cow is a thoughtful, rich film of themes presented unmistakably, but without urgency: they're there for us to pick up and think through at our leisure. It is, in one light, about how the thing called the United States fashioned itself both by imposing itself on the land and being forced to adjust to it, and how systems of exploitation simply appear, fully-formed, without any specific choice made by malicious actors. It affords itself a sentimental streak; in one scene, a Chinese immigrant greets an indigenous native in a Yiddishism, a sweet little tribute to the idea of America as a melting pot. Elsewhere, it glares with bitter, cynical humor at Factor's blithe way of effortlessly steamrolling over the world. It is most decidedly not interested in didacticism, in any direction; it's presenting a broad, all-encompassing portrait of the things that go into "America", which is maybe the thing that Westerns are best at out of all the genres, and Reichardt and her longtime co-writer Jon Raymond (adapting his novel "The Half-Life") do a fantastic job of drawing from the mythic scope of the genre while pinning it down to something specific and unromantic. This is already present right at the start: the film actually opens in the present day, or something like it, on a shot of an ore freighter gradually cutting its way across the exact middle of the frame, and from here a woman (Alia Shawkat) walking her dog in the woods is stunned to find a pair of old skeletons poking out of the dirt. It's a little bit of not much, lingered over at some length while nothing happens but a slow delivery of B-roll, but it immediately contextualises this as a dive into history: Cookie and King-Lu are separated from us by one level of narration, and that level is where film does all of its work of historical commentary and anti-myth.

At the same time, the specific line between present and past is deliberately blurry; the cut between the two happens in the middle of shots of nature, and our only cue that things have changed is that William Tyler's superb score has started its light chiming on the soundtrack. And this is my much less graceful and invisible attempt to transition into another important thing about First Cow, which is that as much as its themes are dense and interesting, they're really not where the film lives. One of Reichardt's greatest strengths lies in her ability to sink into the vibe of a place, and she and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt (collaborating for the fourth time) are doing especially good work in that direction here. First Cow was shot in the boxy, old-fashioned 1.33:1 aspect ratio (as was Meek's Cutoff, Reichardt and Blauvelt's first collaboration), and the film serves as a gorgeous reminder of how well that aspect ratio serves to neatly package human bodies while giving us enough space around them to get a sense of how they're situated in an environment. The geometry of the compositions is never as merciless in pinning the characters as it was in Meek's Cutoff; rather, it situates them, surrounds them. Since Meek's Cutoff is about anxiety in a hostile landscape, while First Cow is about finding a comfortable and nourishing place to live, this emphasis feels just right.

Really, though, the main thing about the movie is just that it lets us and the characters move through it steadily and slowly. It is, at 122 minutes, Reichardt's longest production to date, and it uses that time immaculately well, given that its goal is as much the creation of an aura as it is the recounting of a story, maybe more. Right from its unhurried, more-curious-than-shocked look at the woman finding the skeletons, First Cow wants us to think about these woods of Oregon, past and present. It wants us to think about moving through them, living in them, slowly finding a space in them that feels right. Pure Kelly Reichardt stuff, the same thing we see in all her films, but stately and grander and more confident.

And populated by two exceptionally fine human specimens. In a career overwhelmingly well-supplied with strong characters expressed subtly and elliptically, Cookie and King-Lu still stand out for the simple precision with which the writers sketch them out and the actor soak in them. The fact that the film pivots around one such deep, powerful, and I daresay universal emotional experience - the joy of getting to know somebody new who moves through the world on your exact wavelength - works beautifully with the spare simplicity of the filmmaking: it is a delicate way of teasing out and showcasing an emotion that is, as such things go, very small, while also being very wonderful and warm. There's more to the film than that - Reichardt isn't about to start making fuzzy movies now, and the film's cool depiction of all the ways that power hierarchies can manifest and work their cruelty certainly takes up much of its running time. But that simple kind feeling is definitely a part of it, and it's a kind of warmth that hardly ever shows up in movies, a medium not especially comfortable with depicting friendship. All told, it's a rewarding sprawl of history, emotions, and environments, and while I'm not ready to call it the director's best film yet... well, I did just use the word "yet", didn't I.