Fun, but in no sense civilized

Nobody who ended up in Director Jail has ever deserved it less than Joe Dante. Out of the first six features on which he received sole directorial credit - Piranha (1978), The Howling (1981), Gremlins (1984), Explorers (1985), Innerspace (1987), and The 'Burbs (1989) - only Explorers lost money, and of the remaining five, Innerspace is the only one that even qualifies as a "modest" return on investment. Meanwhile, he'd found a sheltering angel in the form of producer Steven Spielberg, who hand-picked Dante out of horror obscurity to direct one of the segments of 1983's Twilight Zone: The Movie, and produced Gremlins and Innerspace. He was, particularly among genre fans, A Name.

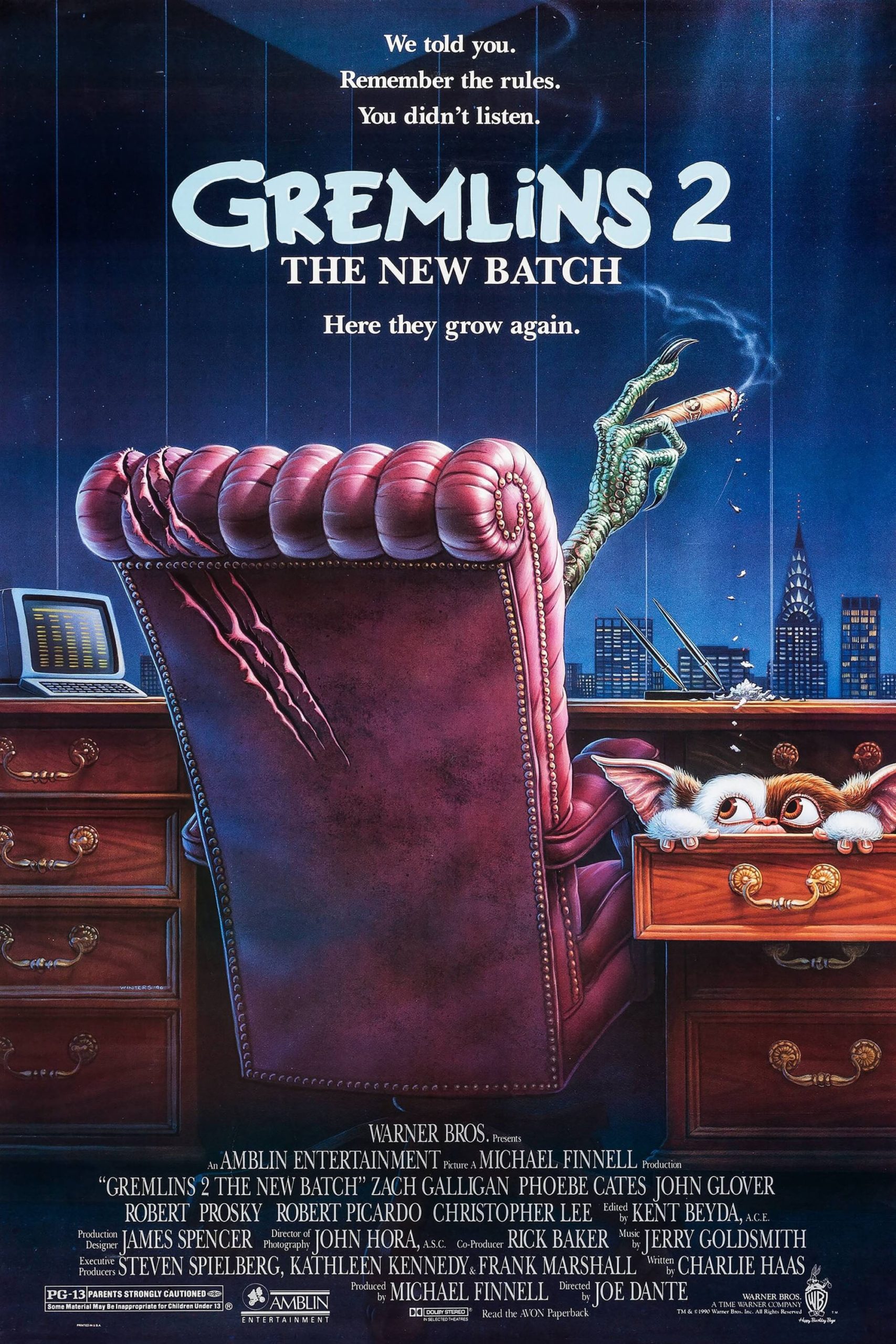

It took only one movie to undo all of this: after 1991, Dante's output dropped to a crawl, with only five features coming between 1993 and 2014, two of them quite obscure, and the only one that came even close to turning a profit was the Spielberg-affiliated Small Soldiers, in 1998. The pity of this was that the film that marks the definitive turn in Dante's fortunes is also, by no little margin, his masterpiece: Gremlins 2: The New Batch, a summer release in 1990 that lost more money than most of his other films cost, having been offered by Warner Bros. in sacrifice as counter-programming to Dick Tracy, Disney's big tentpole that year. I suspect that Warners' knew they had a flop on their hands, and were mostly looking to bury it: while the first Gremlins was a major, major hit in '84, six years is an especially awkward amount of time for a sequel. And even if it wasn't, The New Batch is very much the kind of sequel that, as a studio executive, you look at with a sense of dismay that there's nothing salvageable here, no chance that any number of reshoots are going to make the thing that audiences want. Lo and behold, audiences did not want it, and that reflects entirely poorly on them.

Gremlins 2: The New Batch is the Holy Grail. Many filmmakers throughout the years have tried to figure out how to make a live-action cartoon; Dante, with this film, is the only man I can name that ever got it 100% right. And he himself had already tried multiple times in the past and would try multiple times in the future, without matching this film's triumph (which, to their credit, at least somebody at Warners' knew what a miracle they had on their hands, given that he was given an obviously irresponsible amount of money to make Looney Tunes: Back in Action, his last major studio film, in 2003). Gremlins itself is an attempt to bring the violent slapstick anarchy of a Warner Bros. animated short into the real world, though as great as Gremlins is in its own right, it is only a husk compared to the wildly imaginative extremes that The New Batch could reach with a budget more than four times the size of its predecessor's, and a director who was being given a much freer reign than when he was making his first proper Hollywood movie.

I'm going to spend the rest of this review giving The New Batch a veritable tongue bath, so let me kick things off by mentioning the one problem I have. For the first Gremlins, Jerry Goldsmith wrote a main theme, "The Gremlin Rag", that is among my very favorite pieces of music written by that composer, or in the 1980s, all jangling synths in a nasty parody of a march. "The Gremlin Rag" comes back in The New Batch, but it's mostly used as an undercurrent structuring the rest of the score, and the fullest statement of the melody comes during the end credits suite, where it has been given an expansive new orchestration that plays like a battle between the string and horn sections. It's a perfectly fine orchestration, please understand, and in its own way very funny and sarcastic. But I don't cherish it the way I cherish the tinny squawking of the piece in the first movie. The rest of the score is terrific, nodding towards the way music was used by Carl Stalling in the Looney Tunes of yore, and doing some amazing things with counterpoint - it's just not quite as blatant and hostile, and I really do love that in that first film.

Alright, enough of this "criticism" nonsense. The New Batch is nothing shy of a miracle, a film that absolutely should not exist according to all the norms of Hollywood filmmaking and effects-driven Hollywood franchise filmmaking most of all, and yet it doesn't even feel like it has the limitations of something that had to be smuggled out under cover of darkness. This is just Joe Dante pissing away $50 million on one of the most idiosyncratic movies to ever come remotely near that price tag (the closest analogue I can think of - another early '90s movie made on Warner Bros. money, no less - is Batman Returns, which didn't cost all that much more than The New Batch, and has largely been understood as the studio's "thank you" to Tim Burton for being a team player). The results are certainly weird and not at all expected; where Gremlins is a fairly straightforward horror-comedy in its narrative and mixture of wacky and nihilistic tones, The New Batch is almost completely unconcerned with genre at all, and it glances towards narrative only to sneer at it. It's a celebration of anarchy, and this anarchy is mirrored in its storytelling, which has no pretense towards actual character arcs or even identifiable protagonists, bringing back the central characters from the first movie largely so it can make a big deal about not doing anything with them.

Such as there is a story, it's that several years after the last film, and Mr. Wing (Keye Luke), the old curiosity shop owner in Manhattan's Chinatown who possessed an especially curious curiosity in the form of a small furry creature called a mogwai, is dying. This makes things very easy for the craven business executive Forster (Robert Picardo) - a lot of craven people in The New Batch - who has been waiting for Wing to sell so that he can help his boss demolish the block and replace it with a kind of hideous Chinatown-themed shopping emporium. That boss being a self-regarding dimwit Daniel Clamp (John Glover), a media mogul and real estate tycoon who has no ability to conceive of the world beyond liking shiny new things for the sake that they are shiny. Like a toddler. He's about two-thirds a satire of Donald Trump, one-third a satire of Ted Turner, and honestly I can't name any among the many parody Trumps of that era's pop culture that does a better job of getting at the incurious egotism of the man.

Clamp's newest expression of hideous masturbation is the Clamp Center, a state-of-the-art ultra-modern automated skyscraper that is made entirely out of sharp grey edges and looks perfectly designed for humans to be unable to inhabit it. The mood is right in between Terry Gilliam's Brazil and Jacques Tati's PlayTime and Mon oncle, and it is maybe the best thing I can say about The New Batch that out of all the movies I would ever think to compare to Tati, I don't know if any of them earns it so much. There's an especially Tati-esque joke in the form of the automatic revolving door at the front of the Clamp Center, mentioned only once by the building's omnipresent computer voice (Neil Ross), and then seen in the backgrounds of shots for the rest of the film, always malfunctioning in some new way that neither the film nor the characters bothers to comment on. Visual jokes of this sort - some random bit of wacky business on the side of the frame where the plot isn't happening - are littered all through The New Batch, which takes place in the monstrous Clamp Center less because Dante and screenwriter Charles S. Haas are looking to comment upon modernity than because it's a great source of gags.

Anyway, back to the "story". Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan) and Kate Beringer (Phoebe Cates), the heroes of the last film and now engaged to be married, are both new employees of the Clamp Center - he as a lowest-rung peon in the architecture department, she as a tour guide, forced to wear a remarkably humiliating hat in the shape of the building. The only obvious reason for this is so that the film can have an easy way to dump out its exposition when it turns out that Wing's mogwai, Gizmo (voiced by Howie Mandel), has ended up in the genetic research lab that occupies a floor of the Clamp Center for reasons that even the characters in the movie openly can't figure out. The reason, of course, is so that effects designer Rick Baker can create various gremlins that are genetic hybrids with this or that animal, once Gizmo inevitably gets dowsed by water and thus splits off several new mogwai, who range from the idiotic to the psychopathic. And then these mogwai eat after midnight, and so become the slimy monsters of the title.

I would say, "and then we're off!" but The New Batch has been off since its very first frame. The opening sequence gives away the whole game, as Bugs Bunny (Jeff Bergman) rides the Warner Bros. shield in as part of the studio logo, only to have Daffy Duck (Bergman as well) pop up to complain that the rabbit has spent 50 years overshadowing him (The New Batch arrived in theater 49 years and 11 months after the first official Bugs cartoon, A Wild Hare), and they get into a small fight that, naturally enough, ends with Daffy up making a fool of himself. To make this sequence, Dante managed to convince Chuck Jones to come out of retirement, and while it is impossible to claim that this is Jones at or anywhere near the height of his powers, it tells us right away that horror-comedy is out and pure Looney Tunes madness is in. Though I would argue that the film is much more in line with a Bob Clampett cartoon than a Jones cartoon, not least because Clampett directed Falling Hare and Russian Rhapsody, the two major gremlin shorts that inspired this series in the first place. But Clampett was always more interested in the rubbery physics of cartoon slapstick than Jones. And this is what The New Batch is largely focused on: acts of extreme violence committed by agents of chaos, presented with such bouncy glee both visually and sonically that it never feels like there's even a hint of real weight to it (surely the biggest difference between this sequel and the first Gremlins, which was a substantially nastier dark comedy).

What plays out across the rest of the movie's 106 minutes - longer than it needs to be, especially given how little narrative drive it has, but it doesn't let the momentum flag even a little bit - is almost exclusively gag-based humor built around that indulgent $50 million budget and the effects that it paid for: the wonderfully hideous and angular Clamp Center, wonderfully designed by James H. Spencer, or Baker's menagerie of gremlins and mogwai, substantially more detailed and distinctive than in the last film, with a much greater array of movements available to them. And this is even before the genetic lab comes in and Baker gets to start introduce crazy shit like the gremlin made of vegetables or the spider gremlin. This is the great truth of The New Batch: it exists almost solely to let Dante and his collaborators empty out their fascination with old movies of every sort, and classic Warner animation most of all, and in this respect feels like a deeply private, personal work. But it couldn't possibly exist without the resources of a major studio, and a production model that is particularly hostile to private, personal works.

At any rate, The New Batch definitely doesn't feel like a "one for them" project. It has too many jokes at the expense of contrived, unnecessary sequels, at the grotesquely adorable, ready-to-market cuteness of Gizmo himself (who, accordingly spends very nearly the entire film being tortured by gremlins - like Billy and Kate, the movie has no actual use for him and doesn't pretend otherwise), at the trashy violence of modern action movies - at the idea that they kept making movies after the '50s were over, really. This is all presented with a goofy grin rather than a sharp sneer; the film is having fun with meta-commentary but it means no harm with its satire (hence a Trump/Turner who's more of a goofy dope than a genuine bad actor), no more than it means harm with its various acts of gremlin-on-human and gremlin-on-gremlin and human-on-gremlin violence.

The film's persistently silly attitude might make it seem like trivial fluff; what elevates it instead to the level of masterpiece is the extraordinarily committed filmmaking on display at every turn. The actors are all fully invested in the surface-level caricature the script requires, creating a film populated entirely by broad types who fit perfectly in with the ludicrous world created by the sets and the wide angle lenses favored by cinematographer John Hora in any shot that doesn't demand otherwise. The puppets, gremlin and mogwai, are designed and performed so expressively that it becomes entirely impossible to think of them as anything but characters in a reality that has been perfectly constructed for them to feel perfectly natural.

Or to put it more simply, and repeat myself: this is cinema's all-time finest live-action cartoon. It feels, in every respect, thoroughly fake, but all of the fake elements are so perfectly aligned that it creates its own sense of normalcy and what is possible given the rules being established consistently throughout. It's a lark, a joke for cinephiles and animation buffs; but it is also a lark that marshals all the powers of cinema to create one of the most perfect, energetic, and funny examples of a big studio movie from the great popcorn movie era that ended the 20th Century.

It took only one movie to undo all of this: after 1991, Dante's output dropped to a crawl, with only five features coming between 1993 and 2014, two of them quite obscure, and the only one that came even close to turning a profit was the Spielberg-affiliated Small Soldiers, in 1998. The pity of this was that the film that marks the definitive turn in Dante's fortunes is also, by no little margin, his masterpiece: Gremlins 2: The New Batch, a summer release in 1990 that lost more money than most of his other films cost, having been offered by Warner Bros. in sacrifice as counter-programming to Dick Tracy, Disney's big tentpole that year. I suspect that Warners' knew they had a flop on their hands, and were mostly looking to bury it: while the first Gremlins was a major, major hit in '84, six years is an especially awkward amount of time for a sequel. And even if it wasn't, The New Batch is very much the kind of sequel that, as a studio executive, you look at with a sense of dismay that there's nothing salvageable here, no chance that any number of reshoots are going to make the thing that audiences want. Lo and behold, audiences did not want it, and that reflects entirely poorly on them.

Gremlins 2: The New Batch is the Holy Grail. Many filmmakers throughout the years have tried to figure out how to make a live-action cartoon; Dante, with this film, is the only man I can name that ever got it 100% right. And he himself had already tried multiple times in the past and would try multiple times in the future, without matching this film's triumph (which, to their credit, at least somebody at Warners' knew what a miracle they had on their hands, given that he was given an obviously irresponsible amount of money to make Looney Tunes: Back in Action, his last major studio film, in 2003). Gremlins itself is an attempt to bring the violent slapstick anarchy of a Warner Bros. animated short into the real world, though as great as Gremlins is in its own right, it is only a husk compared to the wildly imaginative extremes that The New Batch could reach with a budget more than four times the size of its predecessor's, and a director who was being given a much freer reign than when he was making his first proper Hollywood movie.

I'm going to spend the rest of this review giving The New Batch a veritable tongue bath, so let me kick things off by mentioning the one problem I have. For the first Gremlins, Jerry Goldsmith wrote a main theme, "The Gremlin Rag", that is among my very favorite pieces of music written by that composer, or in the 1980s, all jangling synths in a nasty parody of a march. "The Gremlin Rag" comes back in The New Batch, but it's mostly used as an undercurrent structuring the rest of the score, and the fullest statement of the melody comes during the end credits suite, where it has been given an expansive new orchestration that plays like a battle between the string and horn sections. It's a perfectly fine orchestration, please understand, and in its own way very funny and sarcastic. But I don't cherish it the way I cherish the tinny squawking of the piece in the first movie. The rest of the score is terrific, nodding towards the way music was used by Carl Stalling in the Looney Tunes of yore, and doing some amazing things with counterpoint - it's just not quite as blatant and hostile, and I really do love that in that first film.

Alright, enough of this "criticism" nonsense. The New Batch is nothing shy of a miracle, a film that absolutely should not exist according to all the norms of Hollywood filmmaking and effects-driven Hollywood franchise filmmaking most of all, and yet it doesn't even feel like it has the limitations of something that had to be smuggled out under cover of darkness. This is just Joe Dante pissing away $50 million on one of the most idiosyncratic movies to ever come remotely near that price tag (the closest analogue I can think of - another early '90s movie made on Warner Bros. money, no less - is Batman Returns, which didn't cost all that much more than The New Batch, and has largely been understood as the studio's "thank you" to Tim Burton for being a team player). The results are certainly weird and not at all expected; where Gremlins is a fairly straightforward horror-comedy in its narrative and mixture of wacky and nihilistic tones, The New Batch is almost completely unconcerned with genre at all, and it glances towards narrative only to sneer at it. It's a celebration of anarchy, and this anarchy is mirrored in its storytelling, which has no pretense towards actual character arcs or even identifiable protagonists, bringing back the central characters from the first movie largely so it can make a big deal about not doing anything with them.

Such as there is a story, it's that several years after the last film, and Mr. Wing (Keye Luke), the old curiosity shop owner in Manhattan's Chinatown who possessed an especially curious curiosity in the form of a small furry creature called a mogwai, is dying. This makes things very easy for the craven business executive Forster (Robert Picardo) - a lot of craven people in The New Batch - who has been waiting for Wing to sell so that he can help his boss demolish the block and replace it with a kind of hideous Chinatown-themed shopping emporium. That boss being a self-regarding dimwit Daniel Clamp (John Glover), a media mogul and real estate tycoon who has no ability to conceive of the world beyond liking shiny new things for the sake that they are shiny. Like a toddler. He's about two-thirds a satire of Donald Trump, one-third a satire of Ted Turner, and honestly I can't name any among the many parody Trumps of that era's pop culture that does a better job of getting at the incurious egotism of the man.

Clamp's newest expression of hideous masturbation is the Clamp Center, a state-of-the-art ultra-modern automated skyscraper that is made entirely out of sharp grey edges and looks perfectly designed for humans to be unable to inhabit it. The mood is right in between Terry Gilliam's Brazil and Jacques Tati's PlayTime and Mon oncle, and it is maybe the best thing I can say about The New Batch that out of all the movies I would ever think to compare to Tati, I don't know if any of them earns it so much. There's an especially Tati-esque joke in the form of the automatic revolving door at the front of the Clamp Center, mentioned only once by the building's omnipresent computer voice (Neil Ross), and then seen in the backgrounds of shots for the rest of the film, always malfunctioning in some new way that neither the film nor the characters bothers to comment on. Visual jokes of this sort - some random bit of wacky business on the side of the frame where the plot isn't happening - are littered all through The New Batch, which takes place in the monstrous Clamp Center less because Dante and screenwriter Charles S. Haas are looking to comment upon modernity than because it's a great source of gags.

Anyway, back to the "story". Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan) and Kate Beringer (Phoebe Cates), the heroes of the last film and now engaged to be married, are both new employees of the Clamp Center - he as a lowest-rung peon in the architecture department, she as a tour guide, forced to wear a remarkably humiliating hat in the shape of the building. The only obvious reason for this is so that the film can have an easy way to dump out its exposition when it turns out that Wing's mogwai, Gizmo (voiced by Howie Mandel), has ended up in the genetic research lab that occupies a floor of the Clamp Center for reasons that even the characters in the movie openly can't figure out. The reason, of course, is so that effects designer Rick Baker can create various gremlins that are genetic hybrids with this or that animal, once Gizmo inevitably gets dowsed by water and thus splits off several new mogwai, who range from the idiotic to the psychopathic. And then these mogwai eat after midnight, and so become the slimy monsters of the title.

I would say, "and then we're off!" but The New Batch has been off since its very first frame. The opening sequence gives away the whole game, as Bugs Bunny (Jeff Bergman) rides the Warner Bros. shield in as part of the studio logo, only to have Daffy Duck (Bergman as well) pop up to complain that the rabbit has spent 50 years overshadowing him (The New Batch arrived in theater 49 years and 11 months after the first official Bugs cartoon, A Wild Hare), and they get into a small fight that, naturally enough, ends with Daffy up making a fool of himself. To make this sequence, Dante managed to convince Chuck Jones to come out of retirement, and while it is impossible to claim that this is Jones at or anywhere near the height of his powers, it tells us right away that horror-comedy is out and pure Looney Tunes madness is in. Though I would argue that the film is much more in line with a Bob Clampett cartoon than a Jones cartoon, not least because Clampett directed Falling Hare and Russian Rhapsody, the two major gremlin shorts that inspired this series in the first place. But Clampett was always more interested in the rubbery physics of cartoon slapstick than Jones. And this is what The New Batch is largely focused on: acts of extreme violence committed by agents of chaos, presented with such bouncy glee both visually and sonically that it never feels like there's even a hint of real weight to it (surely the biggest difference between this sequel and the first Gremlins, which was a substantially nastier dark comedy).

What plays out across the rest of the movie's 106 minutes - longer than it needs to be, especially given how little narrative drive it has, but it doesn't let the momentum flag even a little bit - is almost exclusively gag-based humor built around that indulgent $50 million budget and the effects that it paid for: the wonderfully hideous and angular Clamp Center, wonderfully designed by James H. Spencer, or Baker's menagerie of gremlins and mogwai, substantially more detailed and distinctive than in the last film, with a much greater array of movements available to them. And this is even before the genetic lab comes in and Baker gets to start introduce crazy shit like the gremlin made of vegetables or the spider gremlin. This is the great truth of The New Batch: it exists almost solely to let Dante and his collaborators empty out their fascination with old movies of every sort, and classic Warner animation most of all, and in this respect feels like a deeply private, personal work. But it couldn't possibly exist without the resources of a major studio, and a production model that is particularly hostile to private, personal works.

At any rate, The New Batch definitely doesn't feel like a "one for them" project. It has too many jokes at the expense of contrived, unnecessary sequels, at the grotesquely adorable, ready-to-market cuteness of Gizmo himself (who, accordingly spends very nearly the entire film being tortured by gremlins - like Billy and Kate, the movie has no actual use for him and doesn't pretend otherwise), at the trashy violence of modern action movies - at the idea that they kept making movies after the '50s were over, really. This is all presented with a goofy grin rather than a sharp sneer; the film is having fun with meta-commentary but it means no harm with its satire (hence a Trump/Turner who's more of a goofy dope than a genuine bad actor), no more than it means harm with its various acts of gremlin-on-human and gremlin-on-gremlin and human-on-gremlin violence.

The film's persistently silly attitude might make it seem like trivial fluff; what elevates it instead to the level of masterpiece is the extraordinarily committed filmmaking on display at every turn. The actors are all fully invested in the surface-level caricature the script requires, creating a film populated entirely by broad types who fit perfectly in with the ludicrous world created by the sets and the wide angle lenses favored by cinematographer John Hora in any shot that doesn't demand otherwise. The puppets, gremlin and mogwai, are designed and performed so expressively that it becomes entirely impossible to think of them as anything but characters in a reality that has been perfectly constructed for them to feel perfectly natural.

Or to put it more simply, and repeat myself: this is cinema's all-time finest live-action cartoon. It feels, in every respect, thoroughly fake, but all of the fake elements are so perfectly aligned that it creates its own sense of normalcy and what is possible given the rules being established consistently throughout. It's a lark, a joke for cinephiles and animation buffs; but it is also a lark that marshals all the powers of cinema to create one of the most perfect, energetic, and funny examples of a big studio movie from the great popcorn movie era that ended the 20th Century.