Instead of getting married at once, it sometimes happens we get married at last

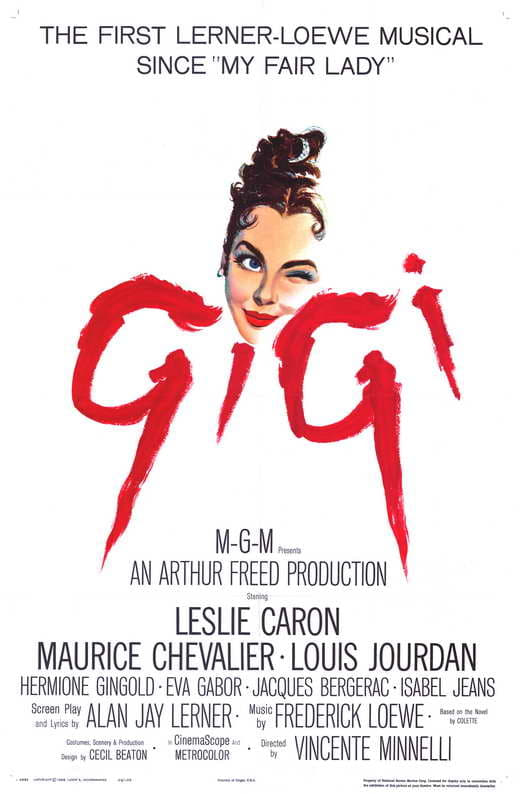

No reviewer of the 1958 MGM musical Gigi will ever come up with a better lede paragraph than the one Bosley Crowther wrote for his review in The New York Times, in which he affects modest shock at the astonishing list of coincidences between the film and a recent Broadway, before drily ending with the observation that "they've come up with a musical film that bears such a basic resemblance to My Fair Lady that [Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe] may want to sue themselves." Crowther goes on to suggest that he doesn't really have a problem with this, and that Gigi still works in its own right, but the point, having been made, hangs there. Gigi absolutely lives in the shadow of My Fair Lady, with a list of original songs that have a virtually one-to-one correspondence, right down to giving not-Henry Higgins some speak-singing in not-"I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face". The comparison, needless to say, does not flatter the movie: My Fair Lady has one of the finest collections of songs in the history of musical theater, and a unbreakable spine in its book, a barely-redressed version of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion. There is still room for Gigi to be good, even great, while being weaker than My Fair Lady - but it is almost impossible not to constantly draw the comparisons.

That cuts two ways, though. In 1958, when Crowther wrote his review, and when producer Arthur Freed (of MGM's legendary musical A-picture production unit; this wasn't the final Freed Unit musical, but it does feel like their valedictory effort) finally got the adaptation of Colette's 1944 novel and Anita Roos's 1951 play based on the novel that he'd been pushing Lerner to write for years, My Fair Lady existed solely as an unimpeachable stage masterpiece. Six years later, My Fair Lady was filmed at Warner Bros., and this, also, invites fairly direct and merciless comparison. And this comparison, at least, Gigi wins falling down. Frankly, the 1964 screen My Fair Lady is about as bad as I can imagine a filmed version of that undefeatable play turning out, barring some horrible attempt at reimagining it; Rex Harrison is visibly irritated, Audrey Hepburn is miscast and receiving no help from director George Cukor, by then in the declining years of his career who himself handles the brightly-based, banter-driven material like a mortician, lacquering the material on expensive but overlit and unattractive sets, not so much staging his actors as pinning them to a board. Gigi, by contrast, has Vincente Minnelli at the height of his powers (I am tempted to say, literally; between this and Some Came Running, I don't see the argument that 1958 wasn't the best year of his career*) using them to do the most Vincente Minnelli thing possible: make the actual city of Paris, where the film's exteriors and some its interiors were all shot, look as beautiful as it has ever looked in a motion picture.

This is as good a point as any to say that there are basically three Gigis. One is a version of Colette's story of a teenage girl whose grandmother and aunt have raised her to be a graceful courtesan in 1900, and the older male friend who is first shocked and then moved to discover that he has fallen in love with her as she has aged into adulthood, all playing out agaist the complicated social politicking of the Parisian upper class. One is Lerne and Loewe's list of songs, which tell an overlapping but meaningfully distinct story about the aging process from childhood to old age. And the last one, and by far the best one is Minnelli's visually orgiastic celebration of the Belle Époque through the means of a film that takes all of its visual cues from the fine arts and architecture of that period. Gigi is an almost unreasonably beautiful film: between them, Minnelli, cinematographer Joseph Ruttenberg, and Cecil Beaton (serving as both production designer and costume designer) have filled every inch of the CinemaScope frame with fussy decor in immaculate complimentary colors, or drenching the Parisian exteriors in warm, golden hues that pull them away from realism and tie them in with the film's embrace of Art Nouveau in all things.

We'll be returning to that. I should at least sketch out the plot, so we're all on the same page: in 1900, strolling through the sensuously dappled walkways of the Bois du Boulogne, we encounter the garrulous old lecher Honoré Lachaille (Maurice Chevalier), who greets us with the unmixed enthusiasm of a born raconteur - basically, Chevalier is playing exactly the same character he played in his late-'20s/early-'30s heyday, hokey and ebullient, and so the minute we enter the film, it has already immediately placed in a headspace that is entirely outdated and oldfashioned and blatantly theatrical - not a bad contrast to the location photography. Honoré shares his unapologetically clichéd worldview of Paris as the world's capital for romance and lust and Parisians as the world's most practiced lovers, and presents a thesis that at every stage of life, one experiences romance differently. He then plucks out Gigi (Leslie Caron), who will be our subject for the next two hours, as we see one particular stage: the arrival into young adulthood and sexual maturity.

Gigi is the granddaughter of one Madame Alvarez, or Mamita (Hermione Gingold), who has arranged for her sister Alicia (Isabel Jeans) to train the girl int the ways of being a courtesan. For while Mamita had her own lusty youth, Alicia was one of the great courtesans, amassing remarkable wealth and comfort. This story runs in parallel to that of Gaston (Louis Jourdan), Honoréś nephew, who has grown immensely bored with the very elaborate performance of social life among the wealthiest Parisians, and is only able to relax around his dear friend Mamita, and Gigi, who he still regards as a playful child who loves candy and cheating at cards.

There's obviously one and only one place this is going to go, and Lerner's script does not take us there without some bumpy writing along the way. Following Colette, the film wants to be a biting, or at least nibbling, commentary on the elaborate social mores of fin de siècle Paris, with Gaston suffering from heavy spiritual ennui as a result of having grown tired of all the tawdry games, and the kindest, most loving figure in the film being a woman who would enthusiastically push her granddaughter towards whoredom and joins her sister in a great belly laugh at the theatrical suicide attempt of Gaston's new ex-mistress (the film joins in - it's surprisingly dark comedy for the period, the studio, and the director, but it works. Metaphorically, Gigi is about how the very beautiful and lush world it depicts was very hard on the people living in it, and how it was in the process of dying away even as everyone in the film is trying to push poor Gigi to embrace it.

This, then, gets us to the songs, which are quietly obsessed with time passing. This is blindingly clear in the three songs given to Chevalier - the film's three best songs, and the only ones that aren't direct My Fair Lady clones (presumably, writing for Chevalier freed up Lerner and Loewe to play with a different musical idiom - which come at the beginning, almost the exact middle, and the end. First, "Thank Heaven for Little Girls" celebrates innocent childhood as the seed from which adulthood will grow; then "I Remember it Well" (almost certainly my favorite song written for a movie in the 1950s) finds Chevalier and Gingold bringing their wildly incompatible performance styles to a rich ironic duet about regret and nostalgia, and warmly reflecting on the road not taken, as the sun literally sets behind them (their exchange "Am I growing old?" / "Oh no, not you" is breathtakingly bittersweet, with Chevalier dialing his performance down just once, to crushing effect). Lastly, backing away from the uncertain melancholy of that song, Honoré wraps up the film by declaring "I'm Glad I'm Not Young Anymore", celebrating old age and senescence as the reward one earns for dealing with all the bullshit of life that is simply not as important as we used to think it was.

In between, Gigi and Gaston's songs capture different aspects of how we perceive the world different as children, young adults, and adults who are starting to see middle age on the horizon. Gigi's "The Parisians" (this film's version of "Why Can't the English?" with a dash of "Just You Wait") is a child's irritated confusion at the adult things she doesn't understand; Gaston's "It's a Bore" ("I'm an Ordinary Man" flavored with "A Hymn to Him") is an adult who has found adulthood isn't what it was promised to be. "The Night They Invented Champagne" ("The Rain in Spain"/"I Could Have Danced All Night") is about tasting the first little joys of adulthood as a late adolescent. And "Gigi" ("I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face") is the summary of all the above, pivoting between anger that children get older and amazement at the adults they grow into (this last song won the Oscar that was part of Gigi's record-setting sweep of nine awards, despite being arguably the worst one in the film)

Weirdly, Lerner's lyrics aren't really backed up by his script, which doesn't really do any of the above (also, the songs make Honoré the film's conscience, while the story makes him closer to a villain, especially in his shockingly brutal suggestion that Gaston will have fun with Gigi for "months", near the end). And this is part of the problem with Gigi: it has no solid foundation. The whole thing is a swirl of scenes that play very well in isolation and kind of pile-up awkwardly on each other (this is worse in the first half, more dominated by songs), of dialogue that sparkles with lightly vicious with and directing that's more ethereal and moody, of performances by the supporting actors that go for big comic stereotypes (not that Chevalier would ever do anything) in the midst of dazzlingly real and tangible sets.

It's mostly made up of strengths, but the strengths don't all fit together, is the thing. And there are things that aren't strengths: Lerner, when he's not borrowing directly from Pygmalion turns out to be not so great at creating rich characters, and nobody in the cast is up to helping him. Least of all Jourdan and Caron, neither of them giving performances I'd even characterise as "good". Jourdan is taking Gaston's protestations of boredm maybe a bit too much to heart, grimacing his way through the first three-quarters of the film without any sort of nuance. Caron is just all over the place, and she's severely overcompensating when she's playing Gigi's adolescent girlishness (she turned 26 during the shoot): during "The Parisians", she jerks her arms around with such energetic zeal that I am terrified she might pull something. She's quite a bit better at playing the mildly sad, more worldly Gigi of the last third of the film, and there are depths here that were completely missing from her previous turn as a gamin in a Minnelli Best Picture winner, 1951's An American in Paris - while it is a thoroughly sexless performance per se, I at least believe in this case that she knows what sex is and finds it melancholic. She also makes quite a bit out of an understated throughline of scenes demonstrating Gigi's enthusiasm for getting drunk. But it's still a pretty shapeless, messy performance.

Shame on her director for not helping her more, but presumably Minnelli was more concerned with crafting some of the most stately, effective compositions of his career. Having put such weight on the sets, Minnelli is damn certain to use them to maximum effect, following the design principles of Art Noveau (airiness, flowing lines) to move his characters throughout spaces and let them feel quite lost amidst the fussy splendor. The film favors long takes and long shots, focusing on characters in their environment rather than their interactions with each other, and in crowd shots, the subject becomes the crowd itself, with the main characters separated from it only subtly, through movement and lighting. The interiors at the legendary restaurant Maxim's are particularly interesting in this respect, both for how aggressively they pursue this strategy, and because Minnelli didn't direct them; they were reshoots conducted months after the bulk of production, directed by Charles Walters - a filmmaker I would never accuse of being visually interesting, but there's something going on with his scenes that feels aggressively painterly and not at all like a normal movie.

The film is a visual masterpiece of the first order, anyway, a remarkable achievement of blocking, color design, lighting, and focal depth; all of this goes into breathing an air of world-weariness that the script claims to have, but never quite manages to demonstrate. It is, in this, kind of the anti-My Fair Lady; wobbly writing redeemed through directing, rather than sterling writing being strangled by its directing. On balance, Gigi could still be much better: while I like Chevalier's three songs a great deal, as well as "The Night They Invented Champagne", there's no pretending that "It's a Bore", "The Parisians", or "The Gossips" ("Ascot Gavotte") are memorable exemplars of songwriting, though the first of these at least has some playful rhymes. And the film would have to be much better for Caron and Jourdan's limited charisma and mediocre acting to avoid being a crushing problem. Still, the film charms me, it's not asking too much with its running time, and it's heart-stoppingly gorgeous. I'd still take An American in Paris if I could only have one, but this is a strong example of MGM, Freed, and Minnelli pooling their strengths to make something whose lavish opulence and glowing color scheme are up to more than just raw spectacle.

P.S. I have nothing to say on the question of whether there's anything creepy or untoward about any of this that wasn't already said much better by Farran Smith Nehme in this 2014 essay. I wouldn't even bring it up, but I don't especially want to be bothered about it in the comments section.

*I don't know, maybe his third 1958 film, The Reluctant Debutante, is the worst piece of shit of the decade, but I doubt it.

That cuts two ways, though. In 1958, when Crowther wrote his review, and when producer Arthur Freed (of MGM's legendary musical A-picture production unit; this wasn't the final Freed Unit musical, but it does feel like their valedictory effort) finally got the adaptation of Colette's 1944 novel and Anita Roos's 1951 play based on the novel that he'd been pushing Lerner to write for years, My Fair Lady existed solely as an unimpeachable stage masterpiece. Six years later, My Fair Lady was filmed at Warner Bros., and this, also, invites fairly direct and merciless comparison. And this comparison, at least, Gigi wins falling down. Frankly, the 1964 screen My Fair Lady is about as bad as I can imagine a filmed version of that undefeatable play turning out, barring some horrible attempt at reimagining it; Rex Harrison is visibly irritated, Audrey Hepburn is miscast and receiving no help from director George Cukor, by then in the declining years of his career who himself handles the brightly-based, banter-driven material like a mortician, lacquering the material on expensive but overlit and unattractive sets, not so much staging his actors as pinning them to a board. Gigi, by contrast, has Vincente Minnelli at the height of his powers (I am tempted to say, literally; between this and Some Came Running, I don't see the argument that 1958 wasn't the best year of his career*) using them to do the most Vincente Minnelli thing possible: make the actual city of Paris, where the film's exteriors and some its interiors were all shot, look as beautiful as it has ever looked in a motion picture.

This is as good a point as any to say that there are basically three Gigis. One is a version of Colette's story of a teenage girl whose grandmother and aunt have raised her to be a graceful courtesan in 1900, and the older male friend who is first shocked and then moved to discover that he has fallen in love with her as she has aged into adulthood, all playing out agaist the complicated social politicking of the Parisian upper class. One is Lerne and Loewe's list of songs, which tell an overlapping but meaningfully distinct story about the aging process from childhood to old age. And the last one, and by far the best one is Minnelli's visually orgiastic celebration of the Belle Époque through the means of a film that takes all of its visual cues from the fine arts and architecture of that period. Gigi is an almost unreasonably beautiful film: between them, Minnelli, cinematographer Joseph Ruttenberg, and Cecil Beaton (serving as both production designer and costume designer) have filled every inch of the CinemaScope frame with fussy decor in immaculate complimentary colors, or drenching the Parisian exteriors in warm, golden hues that pull them away from realism and tie them in with the film's embrace of Art Nouveau in all things.

We'll be returning to that. I should at least sketch out the plot, so we're all on the same page: in 1900, strolling through the sensuously dappled walkways of the Bois du Boulogne, we encounter the garrulous old lecher Honoré Lachaille (Maurice Chevalier), who greets us with the unmixed enthusiasm of a born raconteur - basically, Chevalier is playing exactly the same character he played in his late-'20s/early-'30s heyday, hokey and ebullient, and so the minute we enter the film, it has already immediately placed in a headspace that is entirely outdated and oldfashioned and blatantly theatrical - not a bad contrast to the location photography. Honoré shares his unapologetically clichéd worldview of Paris as the world's capital for romance and lust and Parisians as the world's most practiced lovers, and presents a thesis that at every stage of life, one experiences romance differently. He then plucks out Gigi (Leslie Caron), who will be our subject for the next two hours, as we see one particular stage: the arrival into young adulthood and sexual maturity.

Gigi is the granddaughter of one Madame Alvarez, or Mamita (Hermione Gingold), who has arranged for her sister Alicia (Isabel Jeans) to train the girl int the ways of being a courtesan. For while Mamita had her own lusty youth, Alicia was one of the great courtesans, amassing remarkable wealth and comfort. This story runs in parallel to that of Gaston (Louis Jourdan), Honoréś nephew, who has grown immensely bored with the very elaborate performance of social life among the wealthiest Parisians, and is only able to relax around his dear friend Mamita, and Gigi, who he still regards as a playful child who loves candy and cheating at cards.

There's obviously one and only one place this is going to go, and Lerner's script does not take us there without some bumpy writing along the way. Following Colette, the film wants to be a biting, or at least nibbling, commentary on the elaborate social mores of fin de siècle Paris, with Gaston suffering from heavy spiritual ennui as a result of having grown tired of all the tawdry games, and the kindest, most loving figure in the film being a woman who would enthusiastically push her granddaughter towards whoredom and joins her sister in a great belly laugh at the theatrical suicide attempt of Gaston's new ex-mistress (the film joins in - it's surprisingly dark comedy for the period, the studio, and the director, but it works. Metaphorically, Gigi is about how the very beautiful and lush world it depicts was very hard on the people living in it, and how it was in the process of dying away even as everyone in the film is trying to push poor Gigi to embrace it.

This, then, gets us to the songs, which are quietly obsessed with time passing. This is blindingly clear in the three songs given to Chevalier - the film's three best songs, and the only ones that aren't direct My Fair Lady clones (presumably, writing for Chevalier freed up Lerner and Loewe to play with a different musical idiom - which come at the beginning, almost the exact middle, and the end. First, "Thank Heaven for Little Girls" celebrates innocent childhood as the seed from which adulthood will grow; then "I Remember it Well" (almost certainly my favorite song written for a movie in the 1950s) finds Chevalier and Gingold bringing their wildly incompatible performance styles to a rich ironic duet about regret and nostalgia, and warmly reflecting on the road not taken, as the sun literally sets behind them (their exchange "Am I growing old?" / "Oh no, not you" is breathtakingly bittersweet, with Chevalier dialing his performance down just once, to crushing effect). Lastly, backing away from the uncertain melancholy of that song, Honoré wraps up the film by declaring "I'm Glad I'm Not Young Anymore", celebrating old age and senescence as the reward one earns for dealing with all the bullshit of life that is simply not as important as we used to think it was.

In between, Gigi and Gaston's songs capture different aspects of how we perceive the world different as children, young adults, and adults who are starting to see middle age on the horizon. Gigi's "The Parisians" (this film's version of "Why Can't the English?" with a dash of "Just You Wait") is a child's irritated confusion at the adult things she doesn't understand; Gaston's "It's a Bore" ("I'm an Ordinary Man" flavored with "A Hymn to Him") is an adult who has found adulthood isn't what it was promised to be. "The Night They Invented Champagne" ("The Rain in Spain"/"I Could Have Danced All Night") is about tasting the first little joys of adulthood as a late adolescent. And "Gigi" ("I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face") is the summary of all the above, pivoting between anger that children get older and amazement at the adults they grow into (this last song won the Oscar that was part of Gigi's record-setting sweep of nine awards, despite being arguably the worst one in the film)

Weirdly, Lerner's lyrics aren't really backed up by his script, which doesn't really do any of the above (also, the songs make Honoré the film's conscience, while the story makes him closer to a villain, especially in his shockingly brutal suggestion that Gaston will have fun with Gigi for "months", near the end). And this is part of the problem with Gigi: it has no solid foundation. The whole thing is a swirl of scenes that play very well in isolation and kind of pile-up awkwardly on each other (this is worse in the first half, more dominated by songs), of dialogue that sparkles with lightly vicious with and directing that's more ethereal and moody, of performances by the supporting actors that go for big comic stereotypes (not that Chevalier would ever do anything) in the midst of dazzlingly real and tangible sets.

It's mostly made up of strengths, but the strengths don't all fit together, is the thing. And there are things that aren't strengths: Lerner, when he's not borrowing directly from Pygmalion turns out to be not so great at creating rich characters, and nobody in the cast is up to helping him. Least of all Jourdan and Caron, neither of them giving performances I'd even characterise as "good". Jourdan is taking Gaston's protestations of boredm maybe a bit too much to heart, grimacing his way through the first three-quarters of the film without any sort of nuance. Caron is just all over the place, and she's severely overcompensating when she's playing Gigi's adolescent girlishness (she turned 26 during the shoot): during "The Parisians", she jerks her arms around with such energetic zeal that I am terrified she might pull something. She's quite a bit better at playing the mildly sad, more worldly Gigi of the last third of the film, and there are depths here that were completely missing from her previous turn as a gamin in a Minnelli Best Picture winner, 1951's An American in Paris - while it is a thoroughly sexless performance per se, I at least believe in this case that she knows what sex is and finds it melancholic. She also makes quite a bit out of an understated throughline of scenes demonstrating Gigi's enthusiasm for getting drunk. But it's still a pretty shapeless, messy performance.

Shame on her director for not helping her more, but presumably Minnelli was more concerned with crafting some of the most stately, effective compositions of his career. Having put such weight on the sets, Minnelli is damn certain to use them to maximum effect, following the design principles of Art Noveau (airiness, flowing lines) to move his characters throughout spaces and let them feel quite lost amidst the fussy splendor. The film favors long takes and long shots, focusing on characters in their environment rather than their interactions with each other, and in crowd shots, the subject becomes the crowd itself, with the main characters separated from it only subtly, through movement and lighting. The interiors at the legendary restaurant Maxim's are particularly interesting in this respect, both for how aggressively they pursue this strategy, and because Minnelli didn't direct them; they were reshoots conducted months after the bulk of production, directed by Charles Walters - a filmmaker I would never accuse of being visually interesting, but there's something going on with his scenes that feels aggressively painterly and not at all like a normal movie.

The film is a visual masterpiece of the first order, anyway, a remarkable achievement of blocking, color design, lighting, and focal depth; all of this goes into breathing an air of world-weariness that the script claims to have, but never quite manages to demonstrate. It is, in this, kind of the anti-My Fair Lady; wobbly writing redeemed through directing, rather than sterling writing being strangled by its directing. On balance, Gigi could still be much better: while I like Chevalier's three songs a great deal, as well as "The Night They Invented Champagne", there's no pretending that "It's a Bore", "The Parisians", or "The Gossips" ("Ascot Gavotte") are memorable exemplars of songwriting, though the first of these at least has some playful rhymes. And the film would have to be much better for Caron and Jourdan's limited charisma and mediocre acting to avoid being a crushing problem. Still, the film charms me, it's not asking too much with its running time, and it's heart-stoppingly gorgeous. I'd still take An American in Paris if I could only have one, but this is a strong example of MGM, Freed, and Minnelli pooling their strengths to make something whose lavish opulence and glowing color scheme are up to more than just raw spectacle.

P.S. I have nothing to say on the question of whether there's anything creepy or untoward about any of this that wasn't already said much better by Farran Smith Nehme in this 2014 essay. I wouldn't even bring it up, but I don't especially want to be bothered about it in the comments section.

*I don't know, maybe his third 1958 film, The Reluctant Debutante, is the worst piece of shit of the decade, but I doubt it.