Australian Winter of Blood: I'm on the hunt, I'm after you

The torture porn fad of the mid-'00s was one of the dreariest developments in the history of horror cinema: take the imaginative gore effects of the early slasher films, strip away the merry exploitation hucksterism, and replace it with bitterness and a fascination with the human capacity for cruelty. I have seen at least a majority of the films in question and reviewed a good number of them, and all without enjoying the subgenre even slightly.

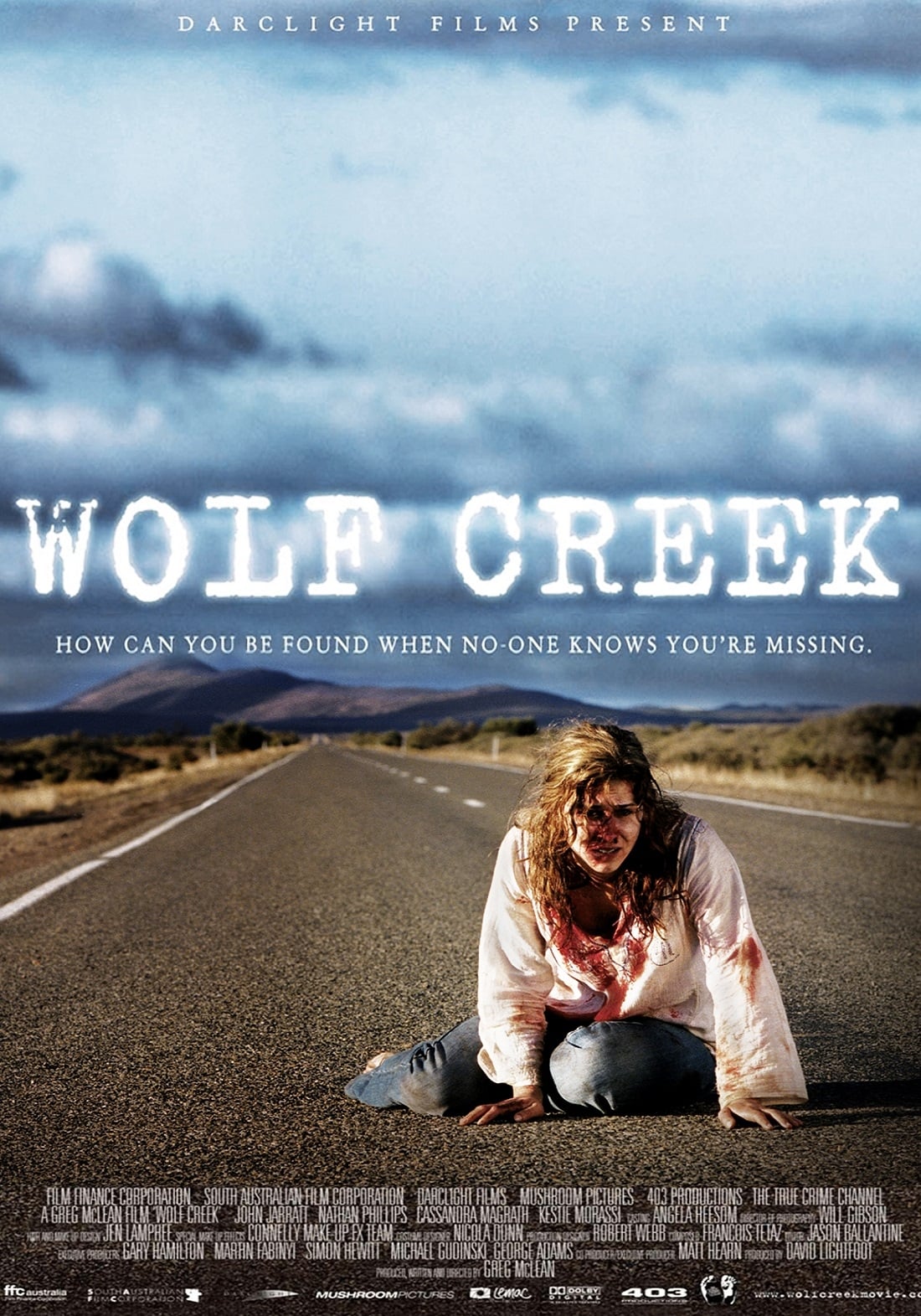

The twist, then, is that we are about to dive into the one torture film that I absolutely love, 2005's Wolf Creek, the debut of writer-director-producer Greg McLean, who has gone on to have a nice, stable career since then, even with a couple of pretty damn good genre films, though nothing that lives up to the promise he shows here. I call this a twist because my affection for Wolf Creek is not in any way due to it being less bitter or cruel than the rest of the torture genre; it is, in fact, arguably more deeply nihilistic than any of them, or at least more sincere in its nihilism. In a sense, it's no different from the likes of Saw: it presents an impossible situation and suggests that no matter how hard the protagonists fight, there isn't actually anyway for them to win. This is, I think, more than the actual torture what defines a torture film: they are hopeless. Even when slasher films pull out the "he's not dead!" card, it at least feels like the protagonists have a reasonable victory condition, and likelier than not they've fulfilled it. Now, a Saw picture views that hopelessness with a certain amount of sneering cynicism. Yeah, everybody dies horribly, but listen to that bitchin' rock soundtrack. Look at that sick production design. Check out all that cool stage blood. We're invited to be disgusted, but we know and the filmmakers know that we don't care; we're there to watch a freak show.

Wolf Creek isn't without purely aesthetic appeal - it is, for one thing, impeccably shot by Will Gibson, maybe even the most beautiful-looking horror film of the 2000s - but it's not bitchin' and it's not cool. It takes hopeless terror very seriously. It has considerably less onscreen violence than any other film of this sort that I've seen, so it lacks that garish, carnivalesque feeling. It is, in its way, a deeply empathetic work: it is a good-faith effort to make us feel completely awful on behalf of the characters and the vicious situation they're going to. If you believe, as I do, that cinema is primarily an emotion-generating machine, Wolf Creek is impeccable cinema: there's not another horror film this side of the 1970s that so effectively makes me feel a deep, despairing misery. This is, in its own way, shocking. We expect horror to be cathartic; it's there to remind us that the monsters can be killed, to repurpose a G.K. Chesterton quote. I think this is why Wolf Creek got such a hostile reception from so many critics: people who disliked this film fucking hated it. But the flipside is that people like me who like the film tend to adore it: it's a faultlessly-made machine for triggering an intense reaction, one that comes from an earnest-good faith desire to make us sympathise with likable people in an unendurable situation. Obviously, nobody is obligated to think this sounds like a fun time at the movies, and while I think this is one of the 21st Century's best made and most effective horror films, it's also one I'm particularly reluctant to recommend without a whole lot of caveats.

So now that we're all good and excited for a fun time at the movies, how does all of this work? The film's biggest trick is to let things develop inordinately slowly, spending almost precisely half of its running time barely ever so much as hinting that it's going to become a horror movie. We open on a pair of twentysomething vagabonds, preparing for a trip across the northern coast of Australian, starting in Broome and ending at the Great Barrier Reef; these are longtime friends Liz (Cassandra Magrath) and Kristy (Kestie Morassi), and their new friend Ben (Nathan Phillips), who has obvious romantic chemistry with Liz, though he claims to be traveling to see his girlfriend on the other side of the continent. Did I say "open on"? Not quite. We open on title cards informing us of the number of people who go missing in Australia, never to be seen again, and this is, for the entire first chunk of the movie, our only indication that things are going to go miserably badly for Liz, Kristy, and Ben.

So this becomes the film's first question: are those cards enough? The first half of Wolf Creek itself has a couple more subdivisions, but it's basically just a slice of young adult life, watching these three figures aimlessly meander through their happily unhurried youth. The sequence before they leave Broome is some excessively shaggy, artless filmmaking, shot by Gibson to accentuate the ugly digital cameras being used and cut by Jason Ballantine with the shapeless, fragmentary roughness of reality TV; spaces don't gel, time doesn't seem to flow, we just see little snapshots of the three having fun with each other and the othering wandering youths they've picked up in Broome. Then the road trip begins, and the filmmaking snaps into a more classical mode, with Gibson capturing some especially beautiful landscape shots; the editing drifts from choppy fragments to ellipses, swirling the roadtrip into a montage of beautiful and playful moments.

With only three characters to focus on, and an interest in the here and now rather than backstory, Wolf Creek is able to use that first hour to sink us into their lives and their carefree mood. I won't lie and tell you that I have a good sense of who any of them are, or that Magrath, Morassi, and Phillips are drawing out deep character beats not present in McLean's script. They're basically just playing kids fucking around, but the film lets them find their rhythm as they're doing so, and it's an enjoyable slice of life: energetic without channeling that energy into a particular direction. The other thing it does, persistently and not always subtly is to lay in a thread of men being no good. The first scene involves Ben awkardly deflecting the leering questions of the car dealer (Guy O'Donnell), who makes unfunny jokes about Ben screwing the two women; later, the women will themselves wonder if Ben is lying about his intentions, because lying is what men do. As they drive into the borderline wilderness, Ben once again finds himself confronted by a whole bar full of leering old men, and this time actually pushes back, immediately caving when they offer a modicum of physical threat. So while it's presenting this carefree hang-out mood, the film is also needling us over and over again with the notion that, left to their own devices, men are dangerous. It never says it's foreshadowing, but...

Again, the film has already strongly implied at at least one of the three will go missing, never to be seen again. So what are we to do with this? The first time I saw the film, I knew it was horror, and the second time I saw it, I knew exactly what would happen and to whom, and both times the film completely suckered me: I watched this the way one watches a road trip movie, with extra-beautiful scenery and flowing cutting to make it all the better. Is that on me? Or is Wolf Creek just that good at foregrounding the main characters? Because the game here, of course, is that the more we like Liz, Kristy, and Ben (and ideally, the more we identify with them), the more horrifying the turn will be. I find it to be extraordinarily good at playing that game.

What happens, at any rate, is that their car breaks down at Wolfe Creek Crater National Park (the film was not shot there, and removes the "E" from "Wolfe" on all signage), and as the afternoon creeps into night, they're found a passerby: Mick Taylor (John Jarratt), who offers to tow them back to his camp at an abandoned mine many miles away, to help fix their car. What he in fact means by "fix their car" is "drug them, torture them, and murder them slowly" - which, as it turns out, is quite a habit of Mick's.

The arrival of Mick knocks Wolf Creek off its axis a little bit even before the moment that he drugs the kids, and a much-too-long fade-to-black ushers in the second half of the film. McLean had a pretty straightforward idea what he wanted the character to be and do: he's mean to be the caricatured vision of Australians the rest of the world has picked up from the likes of Paul Hogan and Steve Irwin, mixed with the real-life serial killer Ivan Milat (which encourages the film to indulge in a dubious "based on a true story" claim). In other words: what if Crocodile Dundee was a slasher movie villain? This turns out to be a surprisingly rich conceit upon which the film can hang itself, not least because the victims themselves grapple a bit with it; they're aware early on that something seems amiss, but Ben dismisses this as unfair mockery of the colorful rural figure who is doing them a favor. Also because it allows Jarratt to blow apart the film with a very different kind of energy and presence than the leads; they're just playing at shaggy realism, he's got a very big, colorful, artificial part to play, and just by arriving with this overt movie-ness, he redirects the film. Once Liz wakes up, and the film's grueling torture-oriented half begins, he redirects it again, taking the broad comic type he's been assigned and adding vicious, monstrous malice to it without fundamentally changing the stereotype he's leaning into; Mick is still a comic Australian goofball, in whatever film he thinks he's starring in, and this in combination with the revolting things he does and the pleasure he takes in doing them creates a shocking charge that the movie able to take quite a long way.

That's one major way Wolf Creek uses a form of blackhearted irony to exaggerate its horror elements. Another is the way it plays the viewer's genre knowledge against us. If you've seen any number of slasher films, you know how this is "supposed to" play out, and it very nastily refuses to. This is particularly true of its violent subversion of the Final Girl sequence, which goes wrong in the most unpleasant way, with the film cutting to avoid showing us anything even more unpleasant (and, of course, encouraging us to imagine the unpleasantness. And that takes us to an extended final act that starts to out-and-out taunt us with little slivers of hope that it then discards.

The second half of Wolf Creek is a rough experience, no two ways about it, with the cinematography making yet another change to ugly artificial lighting creating sharp divides between light and dark spots of the frame; after the beautiful landscapes, it's hostile visually as much as the script is hostile tonally. This, along with the narrative subversion and the weird mismatches in the acting, allow McLean to run us down without ever needing to show anything especially gross or explicit. It's not an especially bloody film at all, let alone an especially bloody horror film. Some of this, no doubt, was budgetary; but it's also good filmmaking. Letting the stage blood fly would make this all easier, somehow, because it would at that point become a typical horror film, letting our grossed-out and/or delighted visceral reaction give us some kind of release. But this isn't a film about release: it's about feeling more and more dreadful and helpless until it stops. Is there "value" to this? Does it even matter? The film packs a punch and makes us confront the miserable ugliness of death and violence in a way that very few films of its genre do, or try to; it's as close to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre as anything I can name after The Texas Chainsaw Massacre itself. I wouldn't want every film to be like this, Christ knows, but every now and then something this potent, coming from such an honestly bleak place, can be pretty amazing stuff.

Body Count: 3 people die onscreen, plus a number of corpses that changes based on which cut you're looking at.

The twist, then, is that we are about to dive into the one torture film that I absolutely love, 2005's Wolf Creek, the debut of writer-director-producer Greg McLean, who has gone on to have a nice, stable career since then, even with a couple of pretty damn good genre films, though nothing that lives up to the promise he shows here. I call this a twist because my affection for Wolf Creek is not in any way due to it being less bitter or cruel than the rest of the torture genre; it is, in fact, arguably more deeply nihilistic than any of them, or at least more sincere in its nihilism. In a sense, it's no different from the likes of Saw: it presents an impossible situation and suggests that no matter how hard the protagonists fight, there isn't actually anyway for them to win. This is, I think, more than the actual torture what defines a torture film: they are hopeless. Even when slasher films pull out the "he's not dead!" card, it at least feels like the protagonists have a reasonable victory condition, and likelier than not they've fulfilled it. Now, a Saw picture views that hopelessness with a certain amount of sneering cynicism. Yeah, everybody dies horribly, but listen to that bitchin' rock soundtrack. Look at that sick production design. Check out all that cool stage blood. We're invited to be disgusted, but we know and the filmmakers know that we don't care; we're there to watch a freak show.

Wolf Creek isn't without purely aesthetic appeal - it is, for one thing, impeccably shot by Will Gibson, maybe even the most beautiful-looking horror film of the 2000s - but it's not bitchin' and it's not cool. It takes hopeless terror very seriously. It has considerably less onscreen violence than any other film of this sort that I've seen, so it lacks that garish, carnivalesque feeling. It is, in its way, a deeply empathetic work: it is a good-faith effort to make us feel completely awful on behalf of the characters and the vicious situation they're going to. If you believe, as I do, that cinema is primarily an emotion-generating machine, Wolf Creek is impeccable cinema: there's not another horror film this side of the 1970s that so effectively makes me feel a deep, despairing misery. This is, in its own way, shocking. We expect horror to be cathartic; it's there to remind us that the monsters can be killed, to repurpose a G.K. Chesterton quote. I think this is why Wolf Creek got such a hostile reception from so many critics: people who disliked this film fucking hated it. But the flipside is that people like me who like the film tend to adore it: it's a faultlessly-made machine for triggering an intense reaction, one that comes from an earnest-good faith desire to make us sympathise with likable people in an unendurable situation. Obviously, nobody is obligated to think this sounds like a fun time at the movies, and while I think this is one of the 21st Century's best made and most effective horror films, it's also one I'm particularly reluctant to recommend without a whole lot of caveats.

So now that we're all good and excited for a fun time at the movies, how does all of this work? The film's biggest trick is to let things develop inordinately slowly, spending almost precisely half of its running time barely ever so much as hinting that it's going to become a horror movie. We open on a pair of twentysomething vagabonds, preparing for a trip across the northern coast of Australian, starting in Broome and ending at the Great Barrier Reef; these are longtime friends Liz (Cassandra Magrath) and Kristy (Kestie Morassi), and their new friend Ben (Nathan Phillips), who has obvious romantic chemistry with Liz, though he claims to be traveling to see his girlfriend on the other side of the continent. Did I say "open on"? Not quite. We open on title cards informing us of the number of people who go missing in Australia, never to be seen again, and this is, for the entire first chunk of the movie, our only indication that things are going to go miserably badly for Liz, Kristy, and Ben.

So this becomes the film's first question: are those cards enough? The first half of Wolf Creek itself has a couple more subdivisions, but it's basically just a slice of young adult life, watching these three figures aimlessly meander through their happily unhurried youth. The sequence before they leave Broome is some excessively shaggy, artless filmmaking, shot by Gibson to accentuate the ugly digital cameras being used and cut by Jason Ballantine with the shapeless, fragmentary roughness of reality TV; spaces don't gel, time doesn't seem to flow, we just see little snapshots of the three having fun with each other and the othering wandering youths they've picked up in Broome. Then the road trip begins, and the filmmaking snaps into a more classical mode, with Gibson capturing some especially beautiful landscape shots; the editing drifts from choppy fragments to ellipses, swirling the roadtrip into a montage of beautiful and playful moments.

With only three characters to focus on, and an interest in the here and now rather than backstory, Wolf Creek is able to use that first hour to sink us into their lives and their carefree mood. I won't lie and tell you that I have a good sense of who any of them are, or that Magrath, Morassi, and Phillips are drawing out deep character beats not present in McLean's script. They're basically just playing kids fucking around, but the film lets them find their rhythm as they're doing so, and it's an enjoyable slice of life: energetic without channeling that energy into a particular direction. The other thing it does, persistently and not always subtly is to lay in a thread of men being no good. The first scene involves Ben awkardly deflecting the leering questions of the car dealer (Guy O'Donnell), who makes unfunny jokes about Ben screwing the two women; later, the women will themselves wonder if Ben is lying about his intentions, because lying is what men do. As they drive into the borderline wilderness, Ben once again finds himself confronted by a whole bar full of leering old men, and this time actually pushes back, immediately caving when they offer a modicum of physical threat. So while it's presenting this carefree hang-out mood, the film is also needling us over and over again with the notion that, left to their own devices, men are dangerous. It never says it's foreshadowing, but...

Again, the film has already strongly implied at at least one of the three will go missing, never to be seen again. So what are we to do with this? The first time I saw the film, I knew it was horror, and the second time I saw it, I knew exactly what would happen and to whom, and both times the film completely suckered me: I watched this the way one watches a road trip movie, with extra-beautiful scenery and flowing cutting to make it all the better. Is that on me? Or is Wolf Creek just that good at foregrounding the main characters? Because the game here, of course, is that the more we like Liz, Kristy, and Ben (and ideally, the more we identify with them), the more horrifying the turn will be. I find it to be extraordinarily good at playing that game.

What happens, at any rate, is that their car breaks down at Wolfe Creek Crater National Park (the film was not shot there, and removes the "E" from "Wolfe" on all signage), and as the afternoon creeps into night, they're found a passerby: Mick Taylor (John Jarratt), who offers to tow them back to his camp at an abandoned mine many miles away, to help fix their car. What he in fact means by "fix their car" is "drug them, torture them, and murder them slowly" - which, as it turns out, is quite a habit of Mick's.

The arrival of Mick knocks Wolf Creek off its axis a little bit even before the moment that he drugs the kids, and a much-too-long fade-to-black ushers in the second half of the film. McLean had a pretty straightforward idea what he wanted the character to be and do: he's mean to be the caricatured vision of Australians the rest of the world has picked up from the likes of Paul Hogan and Steve Irwin, mixed with the real-life serial killer Ivan Milat (which encourages the film to indulge in a dubious "based on a true story" claim). In other words: what if Crocodile Dundee was a slasher movie villain? This turns out to be a surprisingly rich conceit upon which the film can hang itself, not least because the victims themselves grapple a bit with it; they're aware early on that something seems amiss, but Ben dismisses this as unfair mockery of the colorful rural figure who is doing them a favor. Also because it allows Jarratt to blow apart the film with a very different kind of energy and presence than the leads; they're just playing at shaggy realism, he's got a very big, colorful, artificial part to play, and just by arriving with this overt movie-ness, he redirects the film. Once Liz wakes up, and the film's grueling torture-oriented half begins, he redirects it again, taking the broad comic type he's been assigned and adding vicious, monstrous malice to it without fundamentally changing the stereotype he's leaning into; Mick is still a comic Australian goofball, in whatever film he thinks he's starring in, and this in combination with the revolting things he does and the pleasure he takes in doing them creates a shocking charge that the movie able to take quite a long way.

That's one major way Wolf Creek uses a form of blackhearted irony to exaggerate its horror elements. Another is the way it plays the viewer's genre knowledge against us. If you've seen any number of slasher films, you know how this is "supposed to" play out, and it very nastily refuses to. This is particularly true of its violent subversion of the Final Girl sequence, which goes wrong in the most unpleasant way, with the film cutting to avoid showing us anything even more unpleasant (and, of course, encouraging us to imagine the unpleasantness. And that takes us to an extended final act that starts to out-and-out taunt us with little slivers of hope that it then discards.

The second half of Wolf Creek is a rough experience, no two ways about it, with the cinematography making yet another change to ugly artificial lighting creating sharp divides between light and dark spots of the frame; after the beautiful landscapes, it's hostile visually as much as the script is hostile tonally. This, along with the narrative subversion and the weird mismatches in the acting, allow McLean to run us down without ever needing to show anything especially gross or explicit. It's not an especially bloody film at all, let alone an especially bloody horror film. Some of this, no doubt, was budgetary; but it's also good filmmaking. Letting the stage blood fly would make this all easier, somehow, because it would at that point become a typical horror film, letting our grossed-out and/or delighted visceral reaction give us some kind of release. But this isn't a film about release: it's about feeling more and more dreadful and helpless until it stops. Is there "value" to this? Does it even matter? The film packs a punch and makes us confront the miserable ugliness of death and violence in a way that very few films of its genre do, or try to; it's as close to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre as anything I can name after The Texas Chainsaw Massacre itself. I wouldn't want every film to be like this, Christ knows, but every now and then something this potent, coming from such an honestly bleak place, can be pretty amazing stuff.

Body Count: 3 people die onscreen, plus a number of corpses that changes based on which cut you're looking at.