Fear factor

One is practically required by law to start any review of the 1999 version of The Haunting by negatively comparing it to the 1963 version of The Haunting, and how dare I do otherwise. The Haunting '63 is one of horror's all-time highest water marks, an immaculate piece of visual storytelling on top of being a superbly freak plunge into ghostly atmosphere and paranormal freakiness. The Haunting '99 isn't just pissing in the eye of that masterpiece (and Shirley Jackson's excellent 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House that is the remake's only official source), it's the embodiment of all the worst things about American horror filmmaking in the 1990s, burying its handful of effective genre touches beneath a sea of CGI that was ugly then and has aged like roadkill on a humid day. It does this while removing the innuendo and ambiguity that made the earlier incarnations of the story so psychologically troubling, and replacing with repetitive, dumbed-down statements of theme that reduce Jackson's disturbing portraiture into a puzzle box with the solution written on the outside.

The script was the first produced screenplay by David Self, who'd spent the '90s flooding Hollywood with spec scripts, and has since had his name attached to a true-story political procedural (Thirteen Days, 2000), a mournful gangster period piece (Road to Perdition, 2002), and a failed sci-fi pilot (Beyond, 2006), before rounding his way back to revolting, busy horror remakes with 2010's The Wolfman, after which his career seems to have petered out into the usual array of unproduced projects. I say none of this so that we can point at Self and laugh, or whatever, but because this pedigree feels like something of a Rosetta Stone for explaining at least in part why The Haunting turned such a well-built and successfully road-tested story into such a horrid, insulting waste of the viewer's time. It is the kind of thing you get when a stylistic magpie looking to get his foot in the door is tasked by the studio higher-ups with writing a horror picture (the higher-up in the case being Steven Spielberg). It comes from no passion for the genre. It comes from no love of creepy-crawlies and spooks going bump in the night. It comes from a screenwriting manual.

Another part of the explanation is that The Haunting was the fourth and penultimate film directed by ace action cinematographer Jan de Bont, who had leapt up to the big chair with 1994's perfect fine action thriller Speed, a high bar that he never returned to. The clattering and shallow Twister and the infamous Speed 2: Cruise Control followed in '96 and '97, and yet this is still the point where he bottomed out taking all the things he un-learned from those films and applying them to this visually chaotic, effects-driven wallow in the subbest-par haunted house theatrics that I have ever seen in a film with an actual budget to it. The sets are heinously overdesigned by Eugenio Zanetti, creating a morbid old house (played, on the outside and for a couple of its most sedate rooms, by Harlaxton Manor in Lincolnshire) that's a riot of carved wooden cupid heads, hallways full of random sharp edges, and floors that look like what you'd get if Jackson Pollock worked in mosaic, rather than paint. It is, at the very least, an overwhelming quantity of set, but it is not in the slightest bit atmospheric: it throws absolutely everything it can think of at it us without a hint of restraint or modulation, dumping over-the-top Gothic clichés on the screen to make sure we absolutely fucking Get It, this is a weird and wackadoo freaky architectural embodiment of a diseased mind. So, you know, just another way that the film leaves absolutely zero space for us to have a reaction that hasn't been chewed and digested for us in advance.

The story that gets strangled by all of this is sort of like the original, at least to start, if you squint a bit. Eleanor "Nell" Vance (Lili Taylor) has just been thrown out of her home by her godawful sister (Virginia Madsen) and brother-in-law (Tom Irwin), who have been given control of the estate of the sisters' late mother, despite Nell devoting her entire adult life to caring for the decrepit old woman. A pointedly mysterious phone call that bothers her not at all sends Nell to Dr. David Marrow (Liam Neeson), who is running a study on insomniacs. Ah, but as we learn immediately, Marrow is actually tricking insomniacs into spending the night with him in the freaky-looking Hill House, with its long history of murder and death, to study fear. We see him defending this research program with the hugely unimpressed head of his department, a scene that ends uncertainly in a dissolve; presumably the filmmakers wanted to spare us the three hours of scenes it would take to show how in Christ's name Marrow finally managed to get IRB approval, the kind of nitpick I wouldn't feel compelled to throw at the film if the film hadn't thrown it at me first.

At Hill House, Nell meets Marrow's other victims, Theo (Catherine Zeta-Jones) and Luke (Owen Wilson); she also meets the creepy caretakers, Mr. & Mrs. Dudley (Bruce Dern, Marian Seldes), the latter of whom gets to reveal the depth of contempt the film has for its source material when her attempts to set some foreboding atmosphere are turned into a flat bit of exposition. Lastly, we meet Marrow's assistants, Mary (Alix Koromzay) and Todd (Todd Field), though they, like the Dudleys, won't be around long. As Marrow primes the fear pump by starting to tell his "patients" about the strange history of the house - a textile baron in the 19th Century, Hugh Crain, built it to house his family, only to find his wife losing every pregnancy to miscarriage - we get to see, as none of the characters do, an unseen Something tightening the strings on a piano, until the strain causes the string to break, badly slashing Mary's face. She and Todd leave for medical attention, and now it's just a long, gloomy night for Nell, Theo, Luke, and the clearly untrustworthy Marrow.

Right up to about this exact point, I don't actually hate The Haunting. This has almost everything to do with Lili Taylor, a reliable indie film actor who approached this scrip with the same thoughtfulness about how to break her character down for us that she used in working with e.g. Robert Altman. This is something none of her co-stars do: Wilson refuses to budge from his stock "I'm an affable idiot" persona, not even to show a speck of fear or nervousness; Neeson is all but falling asleep before our eyes, presumably to dream of happier days when he wasn't trying to survive these huge dumb CGI extravaganzas (this was later in the same summer as Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace); Zeta-Jones is playing everything with a kind of bug-eyed hamminess, verging on "wacky sitcom neighbor", as her attempt for dealing with the script's disastrous conception of Theo as a character. Back in '63, Theo was coded as a lesbian, the better to serve as a mirror for Nell's deep discomfort with her own sex drive. In '99, Theo has told us by the end of her fifth line of dialogue that she's a polyamorous bisexual, who looks at Nell with the lip-licking hunger of a rattlesnake sizing up a bunny. A horny bunny. This version of the story doesn't actually get around to giving Nell any sexual hang-ups, however, so this has nowhere to go, and so it pretty much evaporates, leaving Theo as just a sharp-tongued antithesis to Morrow's snoozy caution. I don't know if I can imagine the performance that redeems this, but Zeta-Jones, making the immediate decision to go for broad theatricality, definitely isn't on the right track.

But back to Taylor, who really is trying, bless her heart. She keeps the film on track for a goo 25 or 30 minutes of its 113-minute running time, at least functioning as a character study even if it's not a very good one. For one thing, she can't pull focus from the house, and de Bont isn't looking to help her try. He and cinematographer Karl Walter Lindenlaub sent the camera leering into every corner of the tiresomely ornate set, with editor Michael Kahn - Michael fucking Kahn! Spielberg's boy! - obligingly shredding the movie into little jabs of startling angles that make everything look even more gaudily menacing than the production design alone.

It would be very hard to overstate how tacky and garish The Haunting is, at every level. The centerpiece of the house is a portrait of Hugh Crain, lit and posed like a werewolf mid-transformation; there is a carousel room that's a dead ringer for the Boo merry-go-round in Super Mario 64; the room where Nell experiences all the paranormal manifestations at one point turns into a big frowny face with bloodshot googly eyes. The plot, once it starts to unravel, is an over-the-top bit of tawdry melodrama that makes Crain such a nonsensically evil beast that the film's attempts to rein things back in to anything like character psychology feel impossibly forced and insincere. This in turn leads to the spectacle of a finale that is the dumbest bullshit, stupid at the level of story and grotesquely twee at the level of emotion.

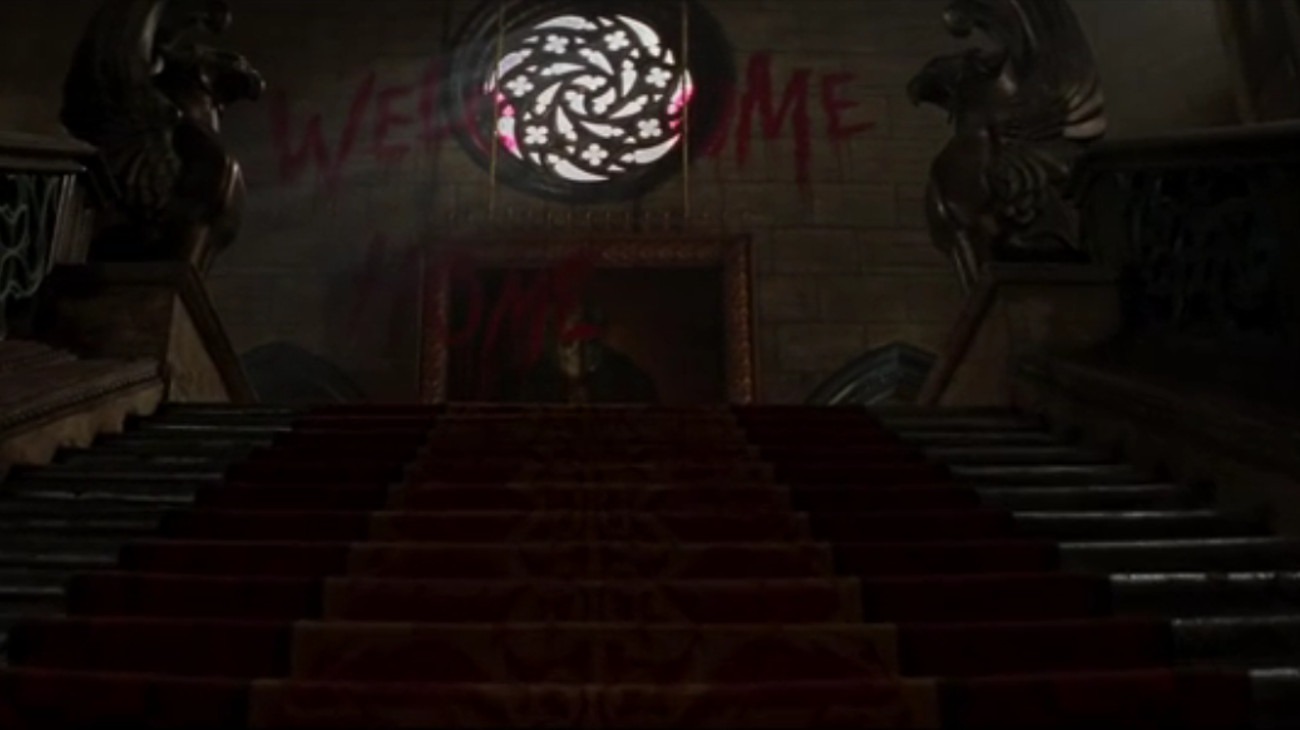

The simplest way to sum it all up: in 1959 and '63, spectral forces manifest the words "Help Eleanor Come Home" on the walls, a deliberately opaque message of uncertain provenance and unclear meaning even after you've finished the story. It is, in some ways, the crux of what makes this such a penetrating, difficult, distressing psychological horror story. In this film? "Welcome Home Eleanor". And that, right there, gets at the difference between the version of this material that's slippery and spooky, and the version that's idiotic popcorn movie bullshit more interested in CGI explosions than unseen, partially-felt creeps, much more eloquently than anything else I could say on the matter.

The script was the first produced screenplay by David Self, who'd spent the '90s flooding Hollywood with spec scripts, and has since had his name attached to a true-story political procedural (Thirteen Days, 2000), a mournful gangster period piece (Road to Perdition, 2002), and a failed sci-fi pilot (Beyond, 2006), before rounding his way back to revolting, busy horror remakes with 2010's The Wolfman, after which his career seems to have petered out into the usual array of unproduced projects. I say none of this so that we can point at Self and laugh, or whatever, but because this pedigree feels like something of a Rosetta Stone for explaining at least in part why The Haunting turned such a well-built and successfully road-tested story into such a horrid, insulting waste of the viewer's time. It is the kind of thing you get when a stylistic magpie looking to get his foot in the door is tasked by the studio higher-ups with writing a horror picture (the higher-up in the case being Steven Spielberg). It comes from no passion for the genre. It comes from no love of creepy-crawlies and spooks going bump in the night. It comes from a screenwriting manual.

Another part of the explanation is that The Haunting was the fourth and penultimate film directed by ace action cinematographer Jan de Bont, who had leapt up to the big chair with 1994's perfect fine action thriller Speed, a high bar that he never returned to. The clattering and shallow Twister and the infamous Speed 2: Cruise Control followed in '96 and '97, and yet this is still the point where he bottomed out taking all the things he un-learned from those films and applying them to this visually chaotic, effects-driven wallow in the subbest-par haunted house theatrics that I have ever seen in a film with an actual budget to it. The sets are heinously overdesigned by Eugenio Zanetti, creating a morbid old house (played, on the outside and for a couple of its most sedate rooms, by Harlaxton Manor in Lincolnshire) that's a riot of carved wooden cupid heads, hallways full of random sharp edges, and floors that look like what you'd get if Jackson Pollock worked in mosaic, rather than paint. It is, at the very least, an overwhelming quantity of set, but it is not in the slightest bit atmospheric: it throws absolutely everything it can think of at it us without a hint of restraint or modulation, dumping over-the-top Gothic clichés on the screen to make sure we absolutely fucking Get It, this is a weird and wackadoo freaky architectural embodiment of a diseased mind. So, you know, just another way that the film leaves absolutely zero space for us to have a reaction that hasn't been chewed and digested for us in advance.

The story that gets strangled by all of this is sort of like the original, at least to start, if you squint a bit. Eleanor "Nell" Vance (Lili Taylor) has just been thrown out of her home by her godawful sister (Virginia Madsen) and brother-in-law (Tom Irwin), who have been given control of the estate of the sisters' late mother, despite Nell devoting her entire adult life to caring for the decrepit old woman. A pointedly mysterious phone call that bothers her not at all sends Nell to Dr. David Marrow (Liam Neeson), who is running a study on insomniacs. Ah, but as we learn immediately, Marrow is actually tricking insomniacs into spending the night with him in the freaky-looking Hill House, with its long history of murder and death, to study fear. We see him defending this research program with the hugely unimpressed head of his department, a scene that ends uncertainly in a dissolve; presumably the filmmakers wanted to spare us the three hours of scenes it would take to show how in Christ's name Marrow finally managed to get IRB approval, the kind of nitpick I wouldn't feel compelled to throw at the film if the film hadn't thrown it at me first.

At Hill House, Nell meets Marrow's other victims, Theo (Catherine Zeta-Jones) and Luke (Owen Wilson); she also meets the creepy caretakers, Mr. & Mrs. Dudley (Bruce Dern, Marian Seldes), the latter of whom gets to reveal the depth of contempt the film has for its source material when her attempts to set some foreboding atmosphere are turned into a flat bit of exposition. Lastly, we meet Marrow's assistants, Mary (Alix Koromzay) and Todd (Todd Field), though they, like the Dudleys, won't be around long. As Marrow primes the fear pump by starting to tell his "patients" about the strange history of the house - a textile baron in the 19th Century, Hugh Crain, built it to house his family, only to find his wife losing every pregnancy to miscarriage - we get to see, as none of the characters do, an unseen Something tightening the strings on a piano, until the strain causes the string to break, badly slashing Mary's face. She and Todd leave for medical attention, and now it's just a long, gloomy night for Nell, Theo, Luke, and the clearly untrustworthy Marrow.

Right up to about this exact point, I don't actually hate The Haunting. This has almost everything to do with Lili Taylor, a reliable indie film actor who approached this scrip with the same thoughtfulness about how to break her character down for us that she used in working with e.g. Robert Altman. This is something none of her co-stars do: Wilson refuses to budge from his stock "I'm an affable idiot" persona, not even to show a speck of fear or nervousness; Neeson is all but falling asleep before our eyes, presumably to dream of happier days when he wasn't trying to survive these huge dumb CGI extravaganzas (this was later in the same summer as Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace); Zeta-Jones is playing everything with a kind of bug-eyed hamminess, verging on "wacky sitcom neighbor", as her attempt for dealing with the script's disastrous conception of Theo as a character. Back in '63, Theo was coded as a lesbian, the better to serve as a mirror for Nell's deep discomfort with her own sex drive. In '99, Theo has told us by the end of her fifth line of dialogue that she's a polyamorous bisexual, who looks at Nell with the lip-licking hunger of a rattlesnake sizing up a bunny. A horny bunny. This version of the story doesn't actually get around to giving Nell any sexual hang-ups, however, so this has nowhere to go, and so it pretty much evaporates, leaving Theo as just a sharp-tongued antithesis to Morrow's snoozy caution. I don't know if I can imagine the performance that redeems this, but Zeta-Jones, making the immediate decision to go for broad theatricality, definitely isn't on the right track.

But back to Taylor, who really is trying, bless her heart. She keeps the film on track for a goo 25 or 30 minutes of its 113-minute running time, at least functioning as a character study even if it's not a very good one. For one thing, she can't pull focus from the house, and de Bont isn't looking to help her try. He and cinematographer Karl Walter Lindenlaub sent the camera leering into every corner of the tiresomely ornate set, with editor Michael Kahn - Michael fucking Kahn! Spielberg's boy! - obligingly shredding the movie into little jabs of startling angles that make everything look even more gaudily menacing than the production design alone.

It would be very hard to overstate how tacky and garish The Haunting is, at every level. The centerpiece of the house is a portrait of Hugh Crain, lit and posed like a werewolf mid-transformation; there is a carousel room that's a dead ringer for the Boo merry-go-round in Super Mario 64; the room where Nell experiences all the paranormal manifestations at one point turns into a big frowny face with bloodshot googly eyes. The plot, once it starts to unravel, is an over-the-top bit of tawdry melodrama that makes Crain such a nonsensically evil beast that the film's attempts to rein things back in to anything like character psychology feel impossibly forced and insincere. This in turn leads to the spectacle of a finale that is the dumbest bullshit, stupid at the level of story and grotesquely twee at the level of emotion.

The simplest way to sum it all up: in 1959 and '63, spectral forces manifest the words "Help Eleanor Come Home" on the walls, a deliberately opaque message of uncertain provenance and unclear meaning even after you've finished the story. It is, in some ways, the crux of what makes this such a penetrating, difficult, distressing psychological horror story. In this film? "Welcome Home Eleanor". And that, right there, gets at the difference between the version of this material that's slippery and spooky, and the version that's idiotic popcorn movie bullshit more interested in CGI explosions than unseen, partially-felt creeps, much more eloquently than anything else I could say on the matter.