PAC man

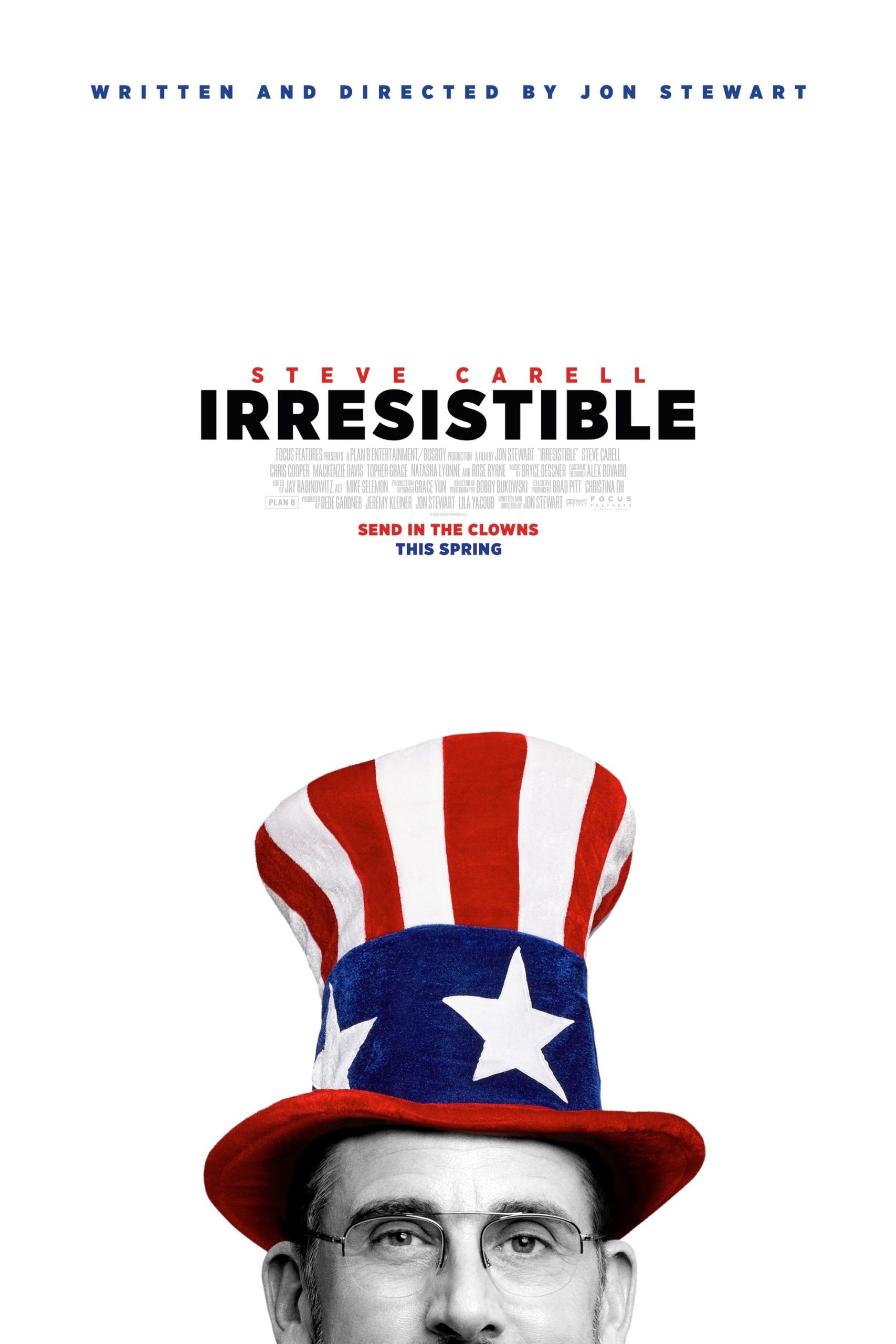

The argument is there to be made that the present moment in American history is so inherently ludicrous that it is immune to satire. I would not want to be the one to make it, but I offer to whomever wants to take the job a peerless piece of evidence in the form of Irresistible. The film finds Jon Stewart, ringleader of The Daily Show when that was the most consistent, beloved satire during the George W. Bush years, turned writer and director (making his second feature in those capacities, after the 2014 journalism biopic Rosewater); and it finds him making little toothless nibbles at a subject that's so cutting edge that this film could have been made in most particulars during the same administration. And it frankly would have felt a bit obvious even then.

None of this would be an insurmountable problem if Irresistible was funny, and it's a little surprising how much it's not. Enough professionally funny people beyond Stewart are involved that it seems like more jokes should work, even if it's just by random chance. As it is, there's only one stretch of the entire film that I, for one, found especially funny at all, and it's almost entirely down to the well-timed editing (by the reliably excellent Jay Rabinowitz and his frequent assistant Mike Selemon, graduated up to a full editor credit), making a snappy comic flow from a montage sequence about the ludicrous high-tech ways that political campaigns can carve up human populations, punctuated by snippy one-liners. I take it to be no coincidence that this is also one of just a few parts of the movie that demonstrates a real sense of why American politics look the way they do, rather than serenely declaring that dumb people make things stupid.

The film centers on a Democratic campaign strategist, Gary Zimmer (former Daily Show correspondent Steve Carell), who like most of his peers was completely blindsided by the 2016 election of Donald Trump to the office of the presidency (his career is introduced in a Forrest Gumpian montage inserting Carell into news footage of various campaign moments in recent history, set to Bob Seger's "Still the Same" - a low-key moment I appreciated for the Seger if nothing else). Desperate for a chance to redeem his professional reputation and his pride - and as a second- or even third-order consideration, to get the Democratic party back on a good track - he pounces on a viral video out of the sleepy, dying town of Deerlaken, Wisconsin, of a Marine veteran named Jack Hastings (Chris Cooper) angrily shouting down the mayor and city council for their shabby social programs and disinterest in helping the poor of the community. Gary sees in this a lightning-in-a-bottle opportunity: passionate leftist rhetoric coming from the mouth of a crusty old white man with a military record. Sensing that he has found her an opportunity to get a Democrat elected in pureblood Republican territory, Gary immediately heads out to Deerlaken, where he starts sinking money into a mayoral campaign, which he sells to the national media as a small-scale referendum on the post-Trump state of partisan politics. This puts the scent of blood in the water, which brings his long-time rival, Republican strategist Faith Brewster (Rose Byrne), to Deerlaken to start sinking money into Jack's Republican opponent.

The film takes its cue from the April 2017 special election to elect a replacement U.S. Representative for Georgia's 6th congressional district, which the two parties turned into a national story about the soul of America; with $50 million spent between the candidates, it was and remains the most expensive House election ever (the results of that election were almost perfectly calibrated to have no meaningful effect on The Discourse, which is part of what makes it a worthy target for satire). Downgrading the office in question from U.S. Representative to small town mayor is, I believe, meant to be one of the jokes, though not one that receives any particular amount of emphasis. Indeed, no joke receives any particular amount of emphasis: Stewart's strategy is to leave the heat down real low, and let the monstrous behavior of Gary, Faith, and their respective teams to slowly reveal its grotesque absurdity only gradually and from the sides.

This maybe even could have worked, and the working version of Irresistible is just inches to the side of the movie we've gotten. The script makes sense if we take it as the story of Gary's blind egotism, his inability to think of rural Wisconsinites as real people (a shortcoming he shares with the film itself, if I may say so), and his technocratic fetish for transforming all human behavior into data, and have the comedy arise out of his pathetic failures as a person. Basically, if it was a Frank Capra movie, now that I think about it. And this is, to an extent, what Irresistible does. The problem is that this is a satire about American electoralism writ large, which means that Gary needs to not be Gary, he needs to be the embodiment of all the problems with professional campaigns; his obnoxious behavior needs to not be about his own personality, but about the systemic structure of American politics.

That's fine if the point of Irresistible is to teach us a lesson, less so if the point is to make a satisfying dramatic narrative: individual people can be the protagonists of drama, overarching systems less so. This is the original sin of message movies. And Irresistible is definitely a message movie, though I honestly don't know what the message is. The end of the movie spells it out for us in no uncertain terms: we need to get money out of politics. But this, aside from being extremely old news to the film's target audience (nostalgic upper-middle class liberals), doesn't actually make sense: what is almost universally meant by "get money out of politics", in my experience, is "get rid of the corrupting influence of money that is used to curry favors and influence decision-making", and Irresistible seems to actually mean "the exchange of money for goods and services has no place in a political campaign". Even so, that never seems to be the actual message of a film that is skewering the ability of politicos to manipulate the media, and the tone-deaf way that coastal elites patronise middle America. Given Stewart's background, it's no surprise that he's much better at doing the former; Irresistible is itself a pretty good example of a patronising elite, though doing so from a bold and exciting new angle that leads to a ridiculous, deeply unsatisfying, inexplicable ending. And this ending does somewhat explain the cartoon portrait of Wisconsin as being maybe slightly more clever than it looks, but given how trite and tacky it looks, that's not saying much.

Whatever the film is trying to say, it is being real smug about saying it. And that smugness is as much a reason as any that the film just isn't funny, nor especially insightful. On top of which, the cast has all been sucked of energy, with Carell barely even waking up and the usually wonderful Byrne taking a frictionless path through a barely-there plot. Mackenzie Davis, still too early in her career to waste opportunities like this, puts some gusto into her bemused reaction shots as Jack's daughter, but the film has very little idea what to do with her prior to the big bad ending, so she spends most of the film feeling like an extra who has somehow finagled her way into having the second-most lines of any character. All in all, a lifeless, sparkless comedy that is far too confident in its wisdom to anything to demonstrate why we should pay attention it; it takes the dire state of film comedy in the United States circa 2020 and marries it to the dire state of political discourse, and the results are exactly what you'd guess.

None of this would be an insurmountable problem if Irresistible was funny, and it's a little surprising how much it's not. Enough professionally funny people beyond Stewart are involved that it seems like more jokes should work, even if it's just by random chance. As it is, there's only one stretch of the entire film that I, for one, found especially funny at all, and it's almost entirely down to the well-timed editing (by the reliably excellent Jay Rabinowitz and his frequent assistant Mike Selemon, graduated up to a full editor credit), making a snappy comic flow from a montage sequence about the ludicrous high-tech ways that political campaigns can carve up human populations, punctuated by snippy one-liners. I take it to be no coincidence that this is also one of just a few parts of the movie that demonstrates a real sense of why American politics look the way they do, rather than serenely declaring that dumb people make things stupid.

The film centers on a Democratic campaign strategist, Gary Zimmer (former Daily Show correspondent Steve Carell), who like most of his peers was completely blindsided by the 2016 election of Donald Trump to the office of the presidency (his career is introduced in a Forrest Gumpian montage inserting Carell into news footage of various campaign moments in recent history, set to Bob Seger's "Still the Same" - a low-key moment I appreciated for the Seger if nothing else). Desperate for a chance to redeem his professional reputation and his pride - and as a second- or even third-order consideration, to get the Democratic party back on a good track - he pounces on a viral video out of the sleepy, dying town of Deerlaken, Wisconsin, of a Marine veteran named Jack Hastings (Chris Cooper) angrily shouting down the mayor and city council for their shabby social programs and disinterest in helping the poor of the community. Gary sees in this a lightning-in-a-bottle opportunity: passionate leftist rhetoric coming from the mouth of a crusty old white man with a military record. Sensing that he has found her an opportunity to get a Democrat elected in pureblood Republican territory, Gary immediately heads out to Deerlaken, where he starts sinking money into a mayoral campaign, which he sells to the national media as a small-scale referendum on the post-Trump state of partisan politics. This puts the scent of blood in the water, which brings his long-time rival, Republican strategist Faith Brewster (Rose Byrne), to Deerlaken to start sinking money into Jack's Republican opponent.

The film takes its cue from the April 2017 special election to elect a replacement U.S. Representative for Georgia's 6th congressional district, which the two parties turned into a national story about the soul of America; with $50 million spent between the candidates, it was and remains the most expensive House election ever (the results of that election were almost perfectly calibrated to have no meaningful effect on The Discourse, which is part of what makes it a worthy target for satire). Downgrading the office in question from U.S. Representative to small town mayor is, I believe, meant to be one of the jokes, though not one that receives any particular amount of emphasis. Indeed, no joke receives any particular amount of emphasis: Stewart's strategy is to leave the heat down real low, and let the monstrous behavior of Gary, Faith, and their respective teams to slowly reveal its grotesque absurdity only gradually and from the sides.

This maybe even could have worked, and the working version of Irresistible is just inches to the side of the movie we've gotten. The script makes sense if we take it as the story of Gary's blind egotism, his inability to think of rural Wisconsinites as real people (a shortcoming he shares with the film itself, if I may say so), and his technocratic fetish for transforming all human behavior into data, and have the comedy arise out of his pathetic failures as a person. Basically, if it was a Frank Capra movie, now that I think about it. And this is, to an extent, what Irresistible does. The problem is that this is a satire about American electoralism writ large, which means that Gary needs to not be Gary, he needs to be the embodiment of all the problems with professional campaigns; his obnoxious behavior needs to not be about his own personality, but about the systemic structure of American politics.

That's fine if the point of Irresistible is to teach us a lesson, less so if the point is to make a satisfying dramatic narrative: individual people can be the protagonists of drama, overarching systems less so. This is the original sin of message movies. And Irresistible is definitely a message movie, though I honestly don't know what the message is. The end of the movie spells it out for us in no uncertain terms: we need to get money out of politics. But this, aside from being extremely old news to the film's target audience (nostalgic upper-middle class liberals), doesn't actually make sense: what is almost universally meant by "get money out of politics", in my experience, is "get rid of the corrupting influence of money that is used to curry favors and influence decision-making", and Irresistible seems to actually mean "the exchange of money for goods and services has no place in a political campaign". Even so, that never seems to be the actual message of a film that is skewering the ability of politicos to manipulate the media, and the tone-deaf way that coastal elites patronise middle America. Given Stewart's background, it's no surprise that he's much better at doing the former; Irresistible is itself a pretty good example of a patronising elite, though doing so from a bold and exciting new angle that leads to a ridiculous, deeply unsatisfying, inexplicable ending. And this ending does somewhat explain the cartoon portrait of Wisconsin as being maybe slightly more clever than it looks, but given how trite and tacky it looks, that's not saying much.

Whatever the film is trying to say, it is being real smug about saying it. And that smugness is as much a reason as any that the film just isn't funny, nor especially insightful. On top of which, the cast has all been sucked of energy, with Carell barely even waking up and the usually wonderful Byrne taking a frictionless path through a barely-there plot. Mackenzie Davis, still too early in her career to waste opportunities like this, puts some gusto into her bemused reaction shots as Jack's daughter, but the film has very little idea what to do with her prior to the big bad ending, so she spends most of the film feeling like an extra who has somehow finagled her way into having the second-most lines of any character. All in all, a lifeless, sparkless comedy that is far too confident in its wisdom to anything to demonstrate why we should pay attention it; it takes the dire state of film comedy in the United States circa 2020 and marries it to the dire state of political discourse, and the results are exactly what you'd guess.