Guilt complex

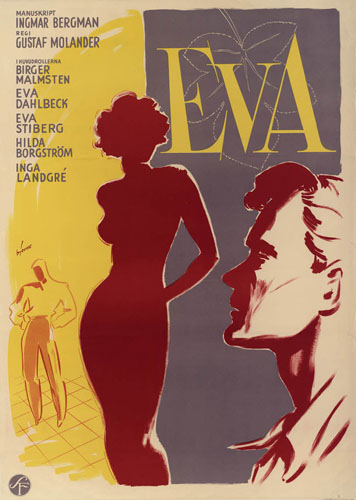

I will begin by confessing that I don't entirely know how to suss out the parentage of Eva, a 1948 Swedish drama. The credits declare that the scenario is by director Gustaf Molander, while the script was written by Ingmar Bergman, and unless the word "scenario" means literally the exact opposite in the Swedish film industry that it does in Hollywood, I'd take that mean that Molander came up with the idea and Bergman turned into a script. But literally every source I can dig up declares instead that Bergman pitched an idea to Svensk Filmindustri right at the start of 1948 and provided a 120-page screenplay for a project then called The Little Trumpet Player and Our Lord; he planned to film it himself, but instead got attached to the project that would eventually emerge as Port of Call, while Molander took on the task of converting Trumpet Player into Eva.

Either way, the film, like the previous year's Molander production of a Bergman script, Woman Without a Face, was broadly taken as a Bergman work despite the direction clearly overriding the writing, to an extent. In the '47 face-off, between that picture and the Bergman-directed A Ship to India, I think Molander chalked up the victory; in '48, between Eva and Port of Call (which preceded Eva to theaters by two and half months), I'd be just as happy and quick to declare victory for Bergman; Eva is a perfectly adequate film, but there's nothing about it that's particularly memorable or special. Its characters are awkwardly expressed and for the most part, indifferently acted; its story is overstuffed and oddly distributed.

The meat of the story is that Bo (Birger Malmsten), serving in Sweden's navy, returns home for the first time in some years, where he finds himself haunted by his past guilt: as a 12-year-old (Lasse Sarri), he was involved in the death of a blind girl, when they stole a locomotive together and he managed to roll it off the tracks, where it exploded (the model used to showcase this event is hilariously unconvincing, enough to make one deeply regret they decided to show it at all). Now, he tries to go about the life of a normal, healthy young man, despite feeling neither healthy nor normal. This includes striking up a new relationship with Eva (Eval Stillberg), a childhood friend, though simply going through the motions is absolutely not sufficient to make him feel good again.

Purely in terms of the theme it explores, this is interesting enough stuff: how a young man obsessed with death can find that obsession coloring his ability to function as a person. A quintessentially Bergman-esque theme, we might even say, though it is easier to say that now than it would have been in 1948, when the heavy gloom of death had not yet shown up anywhere in his career. And one might say, trying to be gentle as possible in doing so, that it was good that it hadn't yet; I won't go all the way to saying that Eva fumbles its heavy ideas, but it certainly doesn't do much with them. The suffocating guilt and hyper-awareness of death the plague Bo and threaten to poison his relationship with Eva is much less of a philosophical conundrum to explore than a plot obstacle to overcome. I will not spoil whether or not it is overcome, but I will say that the late scene where it is at long last confronted is pretty shabby stuff, easily the weakest part of the film; not just because it's a hacky cliché (though it is), but also because the way it's put together feels like a somewhat desperate kludge, relying on the hoary old "superimposed flashback montage" to make sure we get what's happening. And I concede that it wasn't hoary yet in 1948, though it still feels pretty desperate.

The generally superficial feeling that this thematic shallowness gives the film isn't helped at all by Malmsten and Stillberg's simplistic, straightforward performances. There's nothing wrong with them, but they don't do anything to go much beyond the narrative material of the script. This would be less of a problem if Eva didn't have a pair of supporting characters in the form of contentious marrieds Susanne (Eva Dahlbeck) and Göran (Stig Olin); they don't have all that much to do other than give Bo someone else to bounce off of, but Dahlbeck and Olin do dive in and pull things out of their characters that give them precision and personality and a strong sense of unexplored inner lives. Dahlbeck especially; she downright saunters into her scenes, intensely relaxed and unforced in her self-confidence as a robust sensualist. She's both a commanding screen presence and a vivid individual (with a role that's written without individuality, no less), and her relatively brief screentime shows up the film's stars in a way that makes the whole film feel off kilter.

The same is true of its somewhat awkward narrative, which uses a flashback structure that it hasn't quite worked through. The story of Bo's horrible childhood tragedy is told over the course of two very long flashbacks, both in the first third or so of the movie, which is kind of exactly how you don't want to do it. One long flashback at the beginning? Crude, but perfectly effective, especially for '48. Several sequences, interleaved throughout, not letting us learn until close to the end what happened with the train? There would be trade-offs, but it would certainly work. But two different sequences, before dropping the device altogether (unless we count the misguided finale), that's just cluttered and honestly a bit confusing. It hurts the momentum of the present-day story, and promises that the past story is going to be more important in and of itself than ends up being the case.

All that being said, I don't want to harp on Eva too much: it still works, in general. Bergman's storytelling is clumsy, but his character-building is generally strong; Bo is constructed out of asides and innuendo, both his own, and things that others say about him; the relatively limited amount of actual incident in the film means that Bergman can go about doing this work slowly, giving the film a very nice feeling of deliberate, cautious unfurling, that goes well with Bo's own defensiveness and uncertainty. The first act, in particular, is really quite good at contrasting his adult ambivalence with his childhood enthusiasm, drawing interesting connections between who Bo is and how he became that way. It's more interesting as a character study than a relationship drama, and it doesn't always realise this, but when it does, the results can be very effective.

Plus, Molander and cinematographer Åke Dahlqvist are up to some really wonderful things in presenting the material. It lacks the striking noir style of Woman Without a Face, though the basic approach is similar: fairly high contrast, and a lot of busy, restless camera movement slicing through spaces. Here, that camera movement works to create a constant tension between us and Bo, manipulating our distance from him in order to keep us literally at arm's length despite sometimes sliding in closer for intimate moments. It also works to show us the uncertain ways that he occupies the physical spaces in the film, held apart from the other characters in ways that collapse and expand as needed.

It is, all told, a well-built movie, but that's never a phrase that communicates all that much enthusiasm. And there's really not much about Eva to feel enthusiastic about: it's handsome enough, and it's an interesting mile marker on the road to Bergman becoming Bergman. But this is really just a standard-issue '40s relationship drama, with just enough of a well-honed psychological edge that it's not completely anonymous within that genre.

Either way, the film, like the previous year's Molander production of a Bergman script, Woman Without a Face, was broadly taken as a Bergman work despite the direction clearly overriding the writing, to an extent. In the '47 face-off, between that picture and the Bergman-directed A Ship to India, I think Molander chalked up the victory; in '48, between Eva and Port of Call (which preceded Eva to theaters by two and half months), I'd be just as happy and quick to declare victory for Bergman; Eva is a perfectly adequate film, but there's nothing about it that's particularly memorable or special. Its characters are awkwardly expressed and for the most part, indifferently acted; its story is overstuffed and oddly distributed.

The meat of the story is that Bo (Birger Malmsten), serving in Sweden's navy, returns home for the first time in some years, where he finds himself haunted by his past guilt: as a 12-year-old (Lasse Sarri), he was involved in the death of a blind girl, when they stole a locomotive together and he managed to roll it off the tracks, where it exploded (the model used to showcase this event is hilariously unconvincing, enough to make one deeply regret they decided to show it at all). Now, he tries to go about the life of a normal, healthy young man, despite feeling neither healthy nor normal. This includes striking up a new relationship with Eva (Eval Stillberg), a childhood friend, though simply going through the motions is absolutely not sufficient to make him feel good again.

Purely in terms of the theme it explores, this is interesting enough stuff: how a young man obsessed with death can find that obsession coloring his ability to function as a person. A quintessentially Bergman-esque theme, we might even say, though it is easier to say that now than it would have been in 1948, when the heavy gloom of death had not yet shown up anywhere in his career. And one might say, trying to be gentle as possible in doing so, that it was good that it hadn't yet; I won't go all the way to saying that Eva fumbles its heavy ideas, but it certainly doesn't do much with them. The suffocating guilt and hyper-awareness of death the plague Bo and threaten to poison his relationship with Eva is much less of a philosophical conundrum to explore than a plot obstacle to overcome. I will not spoil whether or not it is overcome, but I will say that the late scene where it is at long last confronted is pretty shabby stuff, easily the weakest part of the film; not just because it's a hacky cliché (though it is), but also because the way it's put together feels like a somewhat desperate kludge, relying on the hoary old "superimposed flashback montage" to make sure we get what's happening. And I concede that it wasn't hoary yet in 1948, though it still feels pretty desperate.

The generally superficial feeling that this thematic shallowness gives the film isn't helped at all by Malmsten and Stillberg's simplistic, straightforward performances. There's nothing wrong with them, but they don't do anything to go much beyond the narrative material of the script. This would be less of a problem if Eva didn't have a pair of supporting characters in the form of contentious marrieds Susanne (Eva Dahlbeck) and Göran (Stig Olin); they don't have all that much to do other than give Bo someone else to bounce off of, but Dahlbeck and Olin do dive in and pull things out of their characters that give them precision and personality and a strong sense of unexplored inner lives. Dahlbeck especially; she downright saunters into her scenes, intensely relaxed and unforced in her self-confidence as a robust sensualist. She's both a commanding screen presence and a vivid individual (with a role that's written without individuality, no less), and her relatively brief screentime shows up the film's stars in a way that makes the whole film feel off kilter.

The same is true of its somewhat awkward narrative, which uses a flashback structure that it hasn't quite worked through. The story of Bo's horrible childhood tragedy is told over the course of two very long flashbacks, both in the first third or so of the movie, which is kind of exactly how you don't want to do it. One long flashback at the beginning? Crude, but perfectly effective, especially for '48. Several sequences, interleaved throughout, not letting us learn until close to the end what happened with the train? There would be trade-offs, but it would certainly work. But two different sequences, before dropping the device altogether (unless we count the misguided finale), that's just cluttered and honestly a bit confusing. It hurts the momentum of the present-day story, and promises that the past story is going to be more important in and of itself than ends up being the case.

All that being said, I don't want to harp on Eva too much: it still works, in general. Bergman's storytelling is clumsy, but his character-building is generally strong; Bo is constructed out of asides and innuendo, both his own, and things that others say about him; the relatively limited amount of actual incident in the film means that Bergman can go about doing this work slowly, giving the film a very nice feeling of deliberate, cautious unfurling, that goes well with Bo's own defensiveness and uncertainty. The first act, in particular, is really quite good at contrasting his adult ambivalence with his childhood enthusiasm, drawing interesting connections between who Bo is and how he became that way. It's more interesting as a character study than a relationship drama, and it doesn't always realise this, but when it does, the results can be very effective.

Plus, Molander and cinematographer Åke Dahlqvist are up to some really wonderful things in presenting the material. It lacks the striking noir style of Woman Without a Face, though the basic approach is similar: fairly high contrast, and a lot of busy, restless camera movement slicing through spaces. Here, that camera movement works to create a constant tension between us and Bo, manipulating our distance from him in order to keep us literally at arm's length despite sometimes sliding in closer for intimate moments. It also works to show us the uncertain ways that he occupies the physical spaces in the film, held apart from the other characters in ways that collapse and expand as needed.

It is, all told, a well-built movie, but that's never a phrase that communicates all that much enthusiasm. And there's really not much about Eva to feel enthusiastic about: it's handsome enough, and it's an interesting mile marker on the road to Bergman becoming Bergman. But this is really just a standard-issue '40s relationship drama, with just enough of a well-honed psychological edge that it's not completely anonymous within that genre.