Hell on Earth

In watching the early films of director Ingmar Bergman, it is hard to avoid feeling a certain polite boredom towards them: some are mediocre, some are good, some are very good, but not one of them feels so strikingly different from the kind of serious melodramas being made in northern and western Europe in the post-war era that it's particularly easy to care about them decades later. This is hardly a controversial opinion, and it would appear that one of the people who agreed with it was the young Bergman himself, because literally as soon as he had an opportunity to do so, he broke hard in the direction of something complicated and spiky and difficult and messy, vaguely nodding in the towards the domestic tragedies that had dominated his career, but making something ambitious and messy that he didn't have the means to control just yet. His fifth feature, 1948's Port of Call, was his first substantial box hit in addition to being a significant aesthetic leap forward, and while I have no particularly knowledge to this effect, it seems extremely hard to believe that this proof of his commercial viability wasn't part of what motivated him to approach producer Lorens Marmstedt (with whom he had worked twice before, on A Ship to India and Music in Darkness) with a dream project in hand. Bergman had written an original screenplay he wanted to shoot, the first of his career, and he was willing to take whatever insanely bad deal the producer was willing to offer in order to make it. And it certainly wasn't a great deal: a budget of185,000 kr, astonishingly cheap by the standards of the Swedish industry at the time (the film went over-budget, but it was still pretty cheap), and a meager 18 days to shoot it.

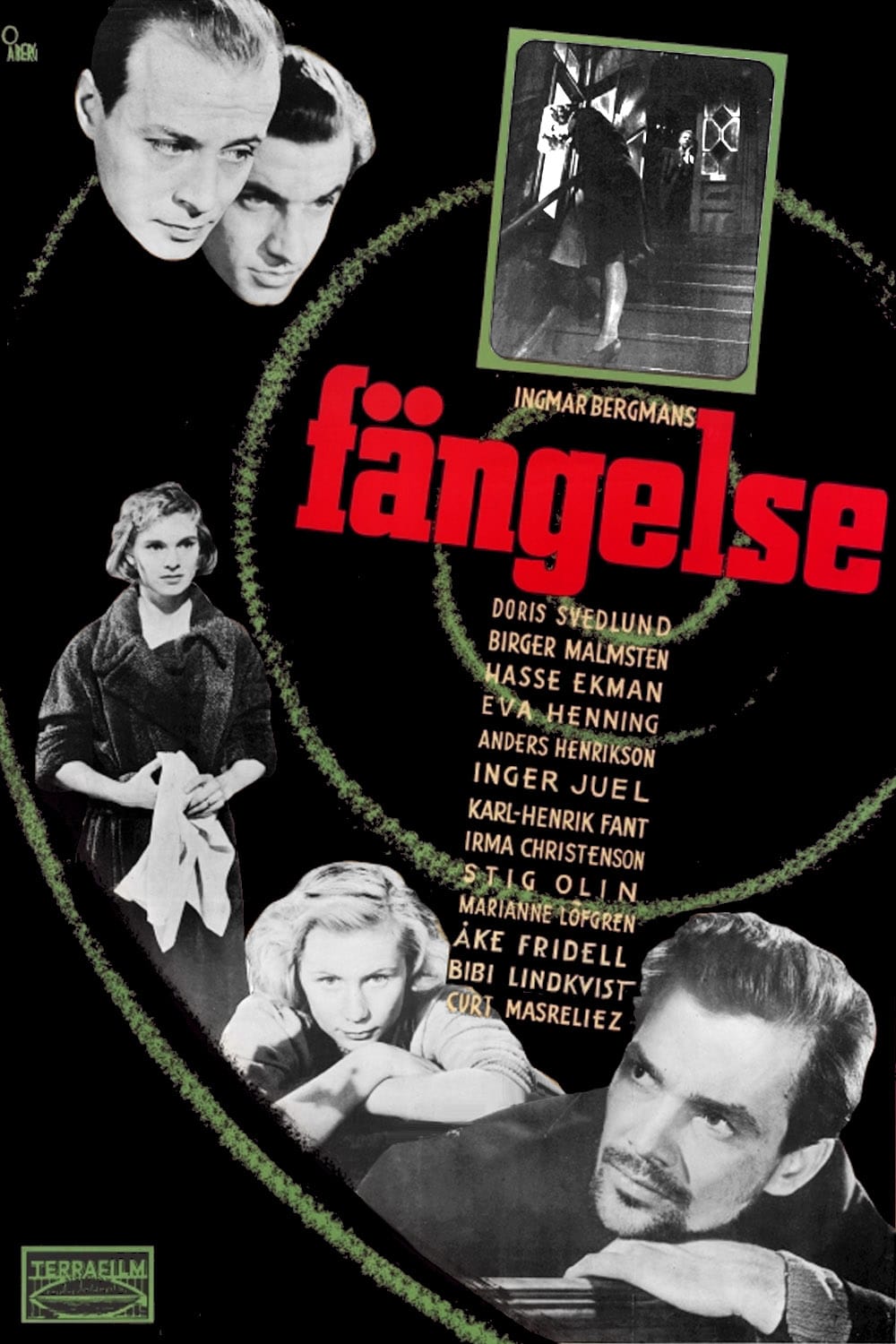

Bergman took the deal, and the result is by far the boldest movie of his career to that point: Prison, a 1949 release that has gone one to be one of the hardest of his features to come by. This is a crying shame on two counts: first, Prison is really the first movie that in any meaningful way resembles "an Ingmar Bergman film" as we have later come to think of that term, and it's a pity that such an important step in his artistic development should be this obscure. Second, it's fucking nuts. I can't name any other films from this period playing the kind of meta-narrative game that Bergman is up to, testing the edge of the cinematic medium in ways that wouldn't become normal until the 1960s. Let us not hide the fact that the experiments of Prison are inconsistently successful: Bergman didn't yet have the level of control that the film needs to work as more than a startling curiosity. And when we get right down to it, this really is basically just another unmelodramatic melodrama with a social conscience, dressed up on the edges with something richer and deeper. But oh! those edges!

The film starts in such a rush that I assumed at first that the copy I'd scrounged up was incomplete: a roar of wind burst onto the soundtrack and a isolated figure off in the distance waddles his way along a lonely dirt road against an empty white sky. A few dissolves take him to the edge of a city, and then into a large brick building that turns out to be a movie studio - he has not yet appeared as anything else but a silhouette, appearing most dramatically as a black figure against a sliver of light through an open door in the pitch-dark studio. Eventually, he walks all the way to a hot set, overseen by a director named Martin (Hasse Ekman, himself a prolific writer and director, and something like Bergman's rival in the media of the day). We learn at this point that our lonely wanderer is Paul (Anders Henrikson), Martin's old math teacher, who has recently been released from a hospital where he was apparently being treated for a mental ailment, and he's got what he claims is a swell idea for a movie. Martin invites him to join the cast and crew's lunch, which is just then being served, and this is where Paul makes his pitch: a movie about Hell. Specifically, a movie about how Hell is already here on Earth, and the Devil's only job is to leave us room to make ourselves miserable.

This turns into a rather heavy, oblique conversation around the table: the first theological debate in Bergman, and the first time that characters openly weigh the extremely likely possibility that God is either dead or banished. And the film is still just warming up: Martin floats the idea by his screenwriters, romantic partners Thomas (Birger Malmsten, sporting a goatee that makes him a substantially more interesting screen presence than in his earlier work with Bergman) and Sofi (Eva Henning, Ekman's wife), and Thomas immediately thinks about connecting it to an article he was trying to write, based on his awkward interview with a 17-year-old prostitute named Birgitta Carolina (Doris Svedlund). As Thomas describes this scenario, it plays out in front of us, lit flatly and played with a wry sense of humor. We then jump back to the room with the three filmmakers, who agree that there's not really a story in this story, and then the film cuts to an exterior street, over which Ekman narrates the opening credits, without any text, as well as declaring that all we've seen so far is just a prologue. Now (according to the narrator) it's six months later, and there's Birgitta again, now promoted to the status of protagonist.

It's a hell of an opening sequence, setting up ideas that are going to be teased out for the rest of the short running time (79 minutes and 75 minutes are the two totals I've seen online; the copy I watched was 74), with more ideas still to come. The most exciting of these isn't necessarily Paul's long, shaggy discussion of the nature of the Devil and Hell (which feels a little too precious if we're meant to take its connection with the rest of the movie literally, and too abstract if we're not), though in giving that sequence privilege of place, Bergman makes sure that it's going to reverberate throughout all the rest of the movie. The self-referential material about the making of a movie and the nature of cinematic storytelling is at least as fresh and arguably more successful. In essence, Prison is about the fact that movies, such as Prison, are artificial constructs, an idea that wasn't brand new in 1949, but was still pretty cutting-edge stuff. This gets played with in a number of ways, starting with Tomas's pitch; the scene of him and Birgitta doesn't stand out particularly when we first see it, except insofar as its blithe sense of humor comes out of nowhere; the stylistic and tonal contrast with their scenes in the rest of the movie reveals this to have been the cleaned-up "movie" version of the relationship that Prison is going to reveal as painful and raw. And this contrast between movies and "reality" keeps showing up all throughout the film, in ways that are connected to the main plot, and otherwise. There is, for example, a very showy moment when Sofi walks onto a set where two actors are in a boat on gimbals in front of a rear-projected ocean: the camera - the one shooting Prison, that is, not the one we see onscreen - pushes forward to the correct position for film their scene, meaning that the illusion of two people in a rocking boat on the open sea is created in an uninterrupted long take, right in front of our eyes. And dammit if it's not convincing, even though we literally watched it being faked, right up until the moment that one of the actors forgets his line and an edit shifts us to an angle on Martin yelling "cut".

The movie spends a lot of time in the early going insisting that we think about the fact that movies are made, so that by the time it arrives at its actual narrative, it has completely muddied our ability to think about what we're watching. The actual narrative, for the record, involves Birgitta's tormented relationship to her pimp and boyfriend Peter (Stig Olin), the probable father of her about-to-be-born baby; he and his associate Linnea (Irma Christenson) are convinced that a newborn will be bad for business, so they arrange to leave the baby somewhere to die of exposure. Broken by this unspeakable savagery, Birgitta flees, meeting up with Tomas, who has descended into a terrible drinking habit, and the two of them spend a night wandering the city, which involves Birgitta getting trapped in an austere nightmare of horror imagery on loan from German Expressionism (gorgeously shot by Göran Strindberg; Bergman makes an effective return to velvety blacks after the sharp grey realism of Gunnar Fischer's work in Port of Call) and symbolism on loan from every armchair dream theorist of the early 20th Century. It's basically the same realistic melodrama that Bergman had been working with since his directorial career began, but the new framework puts an unusual spin on it. For, after all, it's not realistic, and the film has pushed us as hard as possible to realise that movies are fake, and that, in particular, rendering a truly Hellish vision of suffering is quite beyond the means of any filmmaker. So it's hard to know precisely how seriously we're meant to take this. The material of the story is horrible and distressing - so horrible that it feels like overkill almost. Prison presents a tension between the ambition to realise Paul's idea and the impossibility of actually doing so - Martin won't even try, but Bergman tries and... fails? Fails on purpose?

I certainly won't say he succeeds: the film is too diffuse and scattered for that. It's a grab-bag of philosophical and theological conceits, meta-narrative games and social messaging, character psychology and symbolism, and it doesn't come within a mile of combining all of it into a cohesive argument about how movies or people work. The low budget and short shooting schedule are unmistakable in the final product, though the filmmakers have put in a good-faith effort to make the limitations work for them: the spareness of the nightmare sequence or the blunt artlessness of a silent film-within-a-film-within-a-film that renders Hell and the Devil as the subject of slapstick mockery end up working better than a more fully-appointed version of those scenes would have. And to cut down on shot set-ups, Bergman used long takes and more camera movement, taking inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock's 1948 Rope to devise ways of making this approach to yield interesting relationships between the character, the set, and the viewer. Still, Prison feels a bit hollow and incoherent - but this is, in a sense, the film's express theme, the insufficiency of art to truly grapple with things that matter. It is both an effort to define the limits of what cinema is, and an attempt to chart a course to transcend those limits. I think it's no accident that the film introduces ideas about God, the Devil, and suffering that Bergman would grapple with for the rest of his career: more than anything else he'd made up to this point, Prison feels like an essential exercise without which he wouldn't have been able to make those later masterpieces.

Bergman took the deal, and the result is by far the boldest movie of his career to that point: Prison, a 1949 release that has gone one to be one of the hardest of his features to come by. This is a crying shame on two counts: first, Prison is really the first movie that in any meaningful way resembles "an Ingmar Bergman film" as we have later come to think of that term, and it's a pity that such an important step in his artistic development should be this obscure. Second, it's fucking nuts. I can't name any other films from this period playing the kind of meta-narrative game that Bergman is up to, testing the edge of the cinematic medium in ways that wouldn't become normal until the 1960s. Let us not hide the fact that the experiments of Prison are inconsistently successful: Bergman didn't yet have the level of control that the film needs to work as more than a startling curiosity. And when we get right down to it, this really is basically just another unmelodramatic melodrama with a social conscience, dressed up on the edges with something richer and deeper. But oh! those edges!

The film starts in such a rush that I assumed at first that the copy I'd scrounged up was incomplete: a roar of wind burst onto the soundtrack and a isolated figure off in the distance waddles his way along a lonely dirt road against an empty white sky. A few dissolves take him to the edge of a city, and then into a large brick building that turns out to be a movie studio - he has not yet appeared as anything else but a silhouette, appearing most dramatically as a black figure against a sliver of light through an open door in the pitch-dark studio. Eventually, he walks all the way to a hot set, overseen by a director named Martin (Hasse Ekman, himself a prolific writer and director, and something like Bergman's rival in the media of the day). We learn at this point that our lonely wanderer is Paul (Anders Henrikson), Martin's old math teacher, who has recently been released from a hospital where he was apparently being treated for a mental ailment, and he's got what he claims is a swell idea for a movie. Martin invites him to join the cast and crew's lunch, which is just then being served, and this is where Paul makes his pitch: a movie about Hell. Specifically, a movie about how Hell is already here on Earth, and the Devil's only job is to leave us room to make ourselves miserable.

This turns into a rather heavy, oblique conversation around the table: the first theological debate in Bergman, and the first time that characters openly weigh the extremely likely possibility that God is either dead or banished. And the film is still just warming up: Martin floats the idea by his screenwriters, romantic partners Thomas (Birger Malmsten, sporting a goatee that makes him a substantially more interesting screen presence than in his earlier work with Bergman) and Sofi (Eva Henning, Ekman's wife), and Thomas immediately thinks about connecting it to an article he was trying to write, based on his awkward interview with a 17-year-old prostitute named Birgitta Carolina (Doris Svedlund). As Thomas describes this scenario, it plays out in front of us, lit flatly and played with a wry sense of humor. We then jump back to the room with the three filmmakers, who agree that there's not really a story in this story, and then the film cuts to an exterior street, over which Ekman narrates the opening credits, without any text, as well as declaring that all we've seen so far is just a prologue. Now (according to the narrator) it's six months later, and there's Birgitta again, now promoted to the status of protagonist.

It's a hell of an opening sequence, setting up ideas that are going to be teased out for the rest of the short running time (79 minutes and 75 minutes are the two totals I've seen online; the copy I watched was 74), with more ideas still to come. The most exciting of these isn't necessarily Paul's long, shaggy discussion of the nature of the Devil and Hell (which feels a little too precious if we're meant to take its connection with the rest of the movie literally, and too abstract if we're not), though in giving that sequence privilege of place, Bergman makes sure that it's going to reverberate throughout all the rest of the movie. The self-referential material about the making of a movie and the nature of cinematic storytelling is at least as fresh and arguably more successful. In essence, Prison is about the fact that movies, such as Prison, are artificial constructs, an idea that wasn't brand new in 1949, but was still pretty cutting-edge stuff. This gets played with in a number of ways, starting with Tomas's pitch; the scene of him and Birgitta doesn't stand out particularly when we first see it, except insofar as its blithe sense of humor comes out of nowhere; the stylistic and tonal contrast with their scenes in the rest of the movie reveals this to have been the cleaned-up "movie" version of the relationship that Prison is going to reveal as painful and raw. And this contrast between movies and "reality" keeps showing up all throughout the film, in ways that are connected to the main plot, and otherwise. There is, for example, a very showy moment when Sofi walks onto a set where two actors are in a boat on gimbals in front of a rear-projected ocean: the camera - the one shooting Prison, that is, not the one we see onscreen - pushes forward to the correct position for film their scene, meaning that the illusion of two people in a rocking boat on the open sea is created in an uninterrupted long take, right in front of our eyes. And dammit if it's not convincing, even though we literally watched it being faked, right up until the moment that one of the actors forgets his line and an edit shifts us to an angle on Martin yelling "cut".

The movie spends a lot of time in the early going insisting that we think about the fact that movies are made, so that by the time it arrives at its actual narrative, it has completely muddied our ability to think about what we're watching. The actual narrative, for the record, involves Birgitta's tormented relationship to her pimp and boyfriend Peter (Stig Olin), the probable father of her about-to-be-born baby; he and his associate Linnea (Irma Christenson) are convinced that a newborn will be bad for business, so they arrange to leave the baby somewhere to die of exposure. Broken by this unspeakable savagery, Birgitta flees, meeting up with Tomas, who has descended into a terrible drinking habit, and the two of them spend a night wandering the city, which involves Birgitta getting trapped in an austere nightmare of horror imagery on loan from German Expressionism (gorgeously shot by Göran Strindberg; Bergman makes an effective return to velvety blacks after the sharp grey realism of Gunnar Fischer's work in Port of Call) and symbolism on loan from every armchair dream theorist of the early 20th Century. It's basically the same realistic melodrama that Bergman had been working with since his directorial career began, but the new framework puts an unusual spin on it. For, after all, it's not realistic, and the film has pushed us as hard as possible to realise that movies are fake, and that, in particular, rendering a truly Hellish vision of suffering is quite beyond the means of any filmmaker. So it's hard to know precisely how seriously we're meant to take this. The material of the story is horrible and distressing - so horrible that it feels like overkill almost. Prison presents a tension between the ambition to realise Paul's idea and the impossibility of actually doing so - Martin won't even try, but Bergman tries and... fails? Fails on purpose?

I certainly won't say he succeeds: the film is too diffuse and scattered for that. It's a grab-bag of philosophical and theological conceits, meta-narrative games and social messaging, character psychology and symbolism, and it doesn't come within a mile of combining all of it into a cohesive argument about how movies or people work. The low budget and short shooting schedule are unmistakable in the final product, though the filmmakers have put in a good-faith effort to make the limitations work for them: the spareness of the nightmare sequence or the blunt artlessness of a silent film-within-a-film-within-a-film that renders Hell and the Devil as the subject of slapstick mockery end up working better than a more fully-appointed version of those scenes would have. And to cut down on shot set-ups, Bergman used long takes and more camera movement, taking inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock's 1948 Rope to devise ways of making this approach to yield interesting relationships between the character, the set, and the viewer. Still, Prison feels a bit hollow and incoherent - but this is, in a sense, the film's express theme, the insufficiency of art to truly grapple with things that matter. It is both an effort to define the limits of what cinema is, and an attempt to chart a course to transcend those limits. I think it's no accident that the film introduces ideas about God, the Devil, and suffering that Bergman would grapple with for the rest of his career: more than anything else he'd made up to this point, Prison feels like an essential exercise without which he wouldn't have been able to make those later masterpieces.