The rain it raineth every day

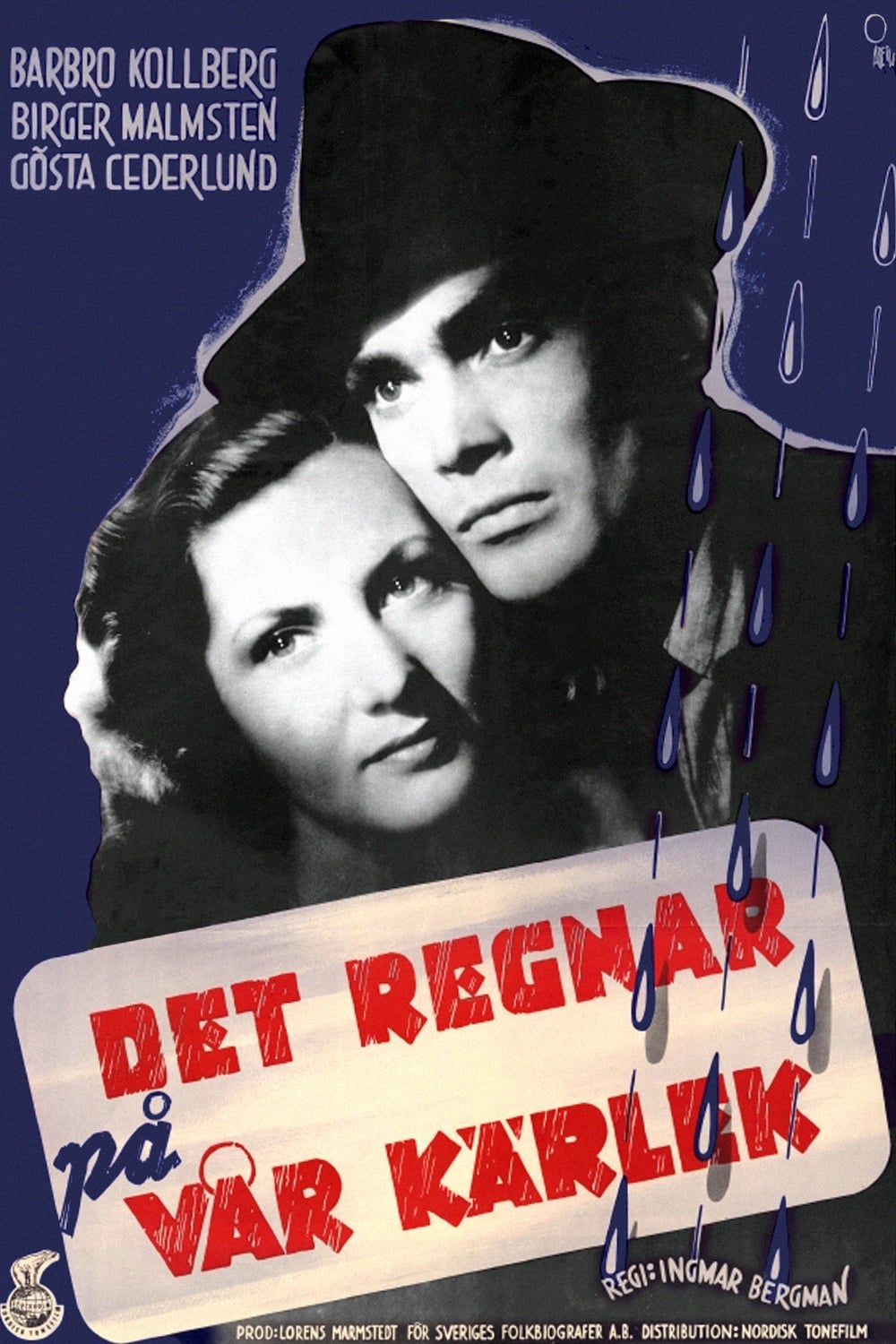

I've already announced my intention that as I work through the early films of director Ingmar Bergman, I'm going to avoid looking too far ahead to his better-known later films. But even if that wasn't the official plan, I'm not sure that I'd have any other option in dealing with his second feature, and one of his most obscure, It Rains on Our Love. Released late in 1946, the same year as his debut film Crisis, it feels very much like the kind of quickly-made studio product implied by that short turnaround time, and the clean, impersonal professionalism implied by the phrase "studio product". It's a chatty, over-plotted romantic melodrama, one made with a fair degree of talent, but not so much that you'd necessarily declare that the man who directed it was clearly somebody to watch. And given that the man who directed it also co-wrote it, with Herbert Grevenius (adapting a Norwegian-language play by Oskar Braaten), one might even go so far as to say that it wouldn't be worth watching him, given that the screenplay is undoubtedly the film's weakest element.

Things get started on a peculiar footing. In the middle of a rainstorm in the midst of a city, the camera cuts closer and closer to a man with an umbrella (Gösta Cederlund), who lifts it up to address the camera directly, ostensibly to tell us a little a bit about the kind of story we're about to hear. He doesn't really do that, and doesn't say who he is, or why he's involved, but he does set the scene on a cold, wet Wednesday in October. He comes back throughout, bending the fourth wall without ever quite breaking it; he imparts upon the film the feeling of being something of a magical realist fable rather than a realistic film story. It's a theatrical device more than a cinematic one, but Bergman and Grevenius have put enough thought into how to reconceive him using cinema's different toolkit, especially voice-over, that it ends up mostly working the film.

The crucial thing, though, is not whether the man with the umbrella ends up working as a narrative device, but what he implies about the film's tone. A fable, I said, and a fable this continues to be, for an act, at least. The first proper character we meet is Maggi (Babro Kollberg), a young woman rushing through a train station in a panic - it will be a while before we learn precisely what is the nature of her woes, but we know that money is one of them, given that her conversation with the ticket-taker consists mostly of asking for the price of less and less desirable tickets, until she finds the one that she can afford. Right after this, she literally trips over David (Birger Malmsten), who has the look of a drifter; their collision costs him his bag of apples and makes her miss her train. Rather than spend the night in the station, he suggests that if they pose as a couple, they can get a bed in the local Salvation Army shelter; he promises not to touch her, but as the night marches into the morning, they have sex - some awfully frank sex by 1946 standards, too.

This is, apparently, enough for them to decide that they're soulmates, because they spend the next day drifting together, looking for a way to make some money; David is, unfortunately, a recently released convict, but it's already looking badly for his prospects without that. By nightfall, nothing has turned up, and they're also out in the country during a hellish rainfall, so they elect to break into an apparently abandoned cottage. No sooner have they started to set up house than the actual owner (Ludde Gentzel) shows up, perfectly willing to throw the desperate young couple to the cops; by the end of a fraught conversation, he's agreed to rent them the place, and helped David ge set up with a job with a local gardener, on top of it.

Everything up to this point works. Much of it has taken place on an inky black, rainy night that sets everything in a sufficiently abstract setting that the vagueness of the storytelling doesn't hurt it, and maybe even becomes an asset. We don't really know who Maggi and David are, and we never really will; we just have to take it on faith that it makes sense for them to get their lives intertwined so quickly, and that we should as a result root for their success. Their smudginess as characters, and their landlords, and the imprecision of where this all takes place, works as long as the film stays wedged in a dreamlike magical realism, and it has so far, with the thick noir-esque cinematography (the film has two credited cinematographers: Göran Strindberg, who would shoot three more films for Bergman in the 1940s, and Hilding Bladh, who'd shoot two, both in the '50s) turning everything into a mysterious, not-of-this world space, far outside the troubles of money and daily life.

The film pursues this angle a little bit. The man with the umbrella comes back, and he's always good to make sure the film stays grounded in that mode of unreality; the movie also subdivides itself into chapters, each of them introduced with a hand-drawn title card, like an illustration from a picture book. And yet, starting with the couple's first morning in the cottage, It Rains on Our Love makes it clear that it wants to be taken seriously as a story of the issues facing everyday people out in the real world. It is, in essence, a message movie about the struggles of young people who haven't established themselves in traversing the smiling but unfriendly governmental bureaucracy, with the additional challenges facing someone with David's crime-ridden past. And Maggi's own past will eventually surface as well. Between the two of the, it's enough to get them in quite a spot of trouble with the overtly kind but judgmental busybodies upon whose indulgence they are obliged to rely. Things get heavy, but never so heavy that this ends up feeling like real tragedy is in the offing; sex aside, it's no more adult than you'd expect to see from any American B-picture on similar themes in the same era.

While I imagine its possible, in an infinite universe, to make a magical realist fable that's also a neorealistic romantic drama about being ground down by an uncaring bureaucracy and the moral judgment of small-minded neighbors, the young Ingmar Bergman didn't have a light enough touch to be the one to make it. The film suffers, a lot, from trying to tap into domestic realism despite having done nothing to set up Maggi and David as anything but archetypes; while Kollberg and Mamlsten are both appealing figures with good chemistry between each other and the camera, they aren't good enough actors to fill their characters with inner lives that aren't there in the writing. Indeed, given how deft a hand Bergman demonstrated with directing actors in Crisis, it's quite a disappointment that nobody in It Rains on Our Love comes across as anything but a generic warm body filling up space on the screen (and this despite including two of Bergman's most important future collaborators, working with him for the first time, Gunnar Björnstrand and Erland Josephson - the latter as an extra rather than a credited actor). It's meant to be a film about individuals facing the community, but neither the individuals nor the community end up being very well-defined. Again, that level of abstract isn't a bother early on, but the more this moves into its busy plot - complete with a scene in a courtroom, the ne plus ultra of uncaring bureaucracies - and the more it appears that the filmmakers actually want to say something about the world today, the more that It Rain on Our Love shows its limitations as a narrative, and Bergman's inability to pull something out of dodgy material. It's only a sophormore effort, and it's perfectly fine and satisfying as a lighthearted, run-of-the-mill '40s melodrama, but look in this film for the promise of a genius with a bright future, and you're not going to find it.

Things get started on a peculiar footing. In the middle of a rainstorm in the midst of a city, the camera cuts closer and closer to a man with an umbrella (Gösta Cederlund), who lifts it up to address the camera directly, ostensibly to tell us a little a bit about the kind of story we're about to hear. He doesn't really do that, and doesn't say who he is, or why he's involved, but he does set the scene on a cold, wet Wednesday in October. He comes back throughout, bending the fourth wall without ever quite breaking it; he imparts upon the film the feeling of being something of a magical realist fable rather than a realistic film story. It's a theatrical device more than a cinematic one, but Bergman and Grevenius have put enough thought into how to reconceive him using cinema's different toolkit, especially voice-over, that it ends up mostly working the film.

The crucial thing, though, is not whether the man with the umbrella ends up working as a narrative device, but what he implies about the film's tone. A fable, I said, and a fable this continues to be, for an act, at least. The first proper character we meet is Maggi (Babro Kollberg), a young woman rushing through a train station in a panic - it will be a while before we learn precisely what is the nature of her woes, but we know that money is one of them, given that her conversation with the ticket-taker consists mostly of asking for the price of less and less desirable tickets, until she finds the one that she can afford. Right after this, she literally trips over David (Birger Malmsten), who has the look of a drifter; their collision costs him his bag of apples and makes her miss her train. Rather than spend the night in the station, he suggests that if they pose as a couple, they can get a bed in the local Salvation Army shelter; he promises not to touch her, but as the night marches into the morning, they have sex - some awfully frank sex by 1946 standards, too.

This is, apparently, enough for them to decide that they're soulmates, because they spend the next day drifting together, looking for a way to make some money; David is, unfortunately, a recently released convict, but it's already looking badly for his prospects without that. By nightfall, nothing has turned up, and they're also out in the country during a hellish rainfall, so they elect to break into an apparently abandoned cottage. No sooner have they started to set up house than the actual owner (Ludde Gentzel) shows up, perfectly willing to throw the desperate young couple to the cops; by the end of a fraught conversation, he's agreed to rent them the place, and helped David ge set up with a job with a local gardener, on top of it.

Everything up to this point works. Much of it has taken place on an inky black, rainy night that sets everything in a sufficiently abstract setting that the vagueness of the storytelling doesn't hurt it, and maybe even becomes an asset. We don't really know who Maggi and David are, and we never really will; we just have to take it on faith that it makes sense for them to get their lives intertwined so quickly, and that we should as a result root for their success. Their smudginess as characters, and their landlords, and the imprecision of where this all takes place, works as long as the film stays wedged in a dreamlike magical realism, and it has so far, with the thick noir-esque cinematography (the film has two credited cinematographers: Göran Strindberg, who would shoot three more films for Bergman in the 1940s, and Hilding Bladh, who'd shoot two, both in the '50s) turning everything into a mysterious, not-of-this world space, far outside the troubles of money and daily life.

The film pursues this angle a little bit. The man with the umbrella comes back, and he's always good to make sure the film stays grounded in that mode of unreality; the movie also subdivides itself into chapters, each of them introduced with a hand-drawn title card, like an illustration from a picture book. And yet, starting with the couple's first morning in the cottage, It Rains on Our Love makes it clear that it wants to be taken seriously as a story of the issues facing everyday people out in the real world. It is, in essence, a message movie about the struggles of young people who haven't established themselves in traversing the smiling but unfriendly governmental bureaucracy, with the additional challenges facing someone with David's crime-ridden past. And Maggi's own past will eventually surface as well. Between the two of the, it's enough to get them in quite a spot of trouble with the overtly kind but judgmental busybodies upon whose indulgence they are obliged to rely. Things get heavy, but never so heavy that this ends up feeling like real tragedy is in the offing; sex aside, it's no more adult than you'd expect to see from any American B-picture on similar themes in the same era.

While I imagine its possible, in an infinite universe, to make a magical realist fable that's also a neorealistic romantic drama about being ground down by an uncaring bureaucracy and the moral judgment of small-minded neighbors, the young Ingmar Bergman didn't have a light enough touch to be the one to make it. The film suffers, a lot, from trying to tap into domestic realism despite having done nothing to set up Maggi and David as anything but archetypes; while Kollberg and Mamlsten are both appealing figures with good chemistry between each other and the camera, they aren't good enough actors to fill their characters with inner lives that aren't there in the writing. Indeed, given how deft a hand Bergman demonstrated with directing actors in Crisis, it's quite a disappointment that nobody in It Rains on Our Love comes across as anything but a generic warm body filling up space on the screen (and this despite including two of Bergman's most important future collaborators, working with him for the first time, Gunnar Björnstrand and Erland Josephson - the latter as an extra rather than a credited actor). It's meant to be a film about individuals facing the community, but neither the individuals nor the community end up being very well-defined. Again, that level of abstract isn't a bother early on, but the more this moves into its busy plot - complete with a scene in a courtroom, the ne plus ultra of uncaring bureaucracies - and the more it appears that the filmmakers actually want to say something about the world today, the more that It Rain on Our Love shows its limitations as a narrative, and Bergman's inability to pull something out of dodgy material. It's only a sophormore effort, and it's perfectly fine and satisfying as a lighthearted, run-of-the-mill '40s melodrama, but look in this film for the promise of a genius with a bright future, and you're not going to find it.