In country

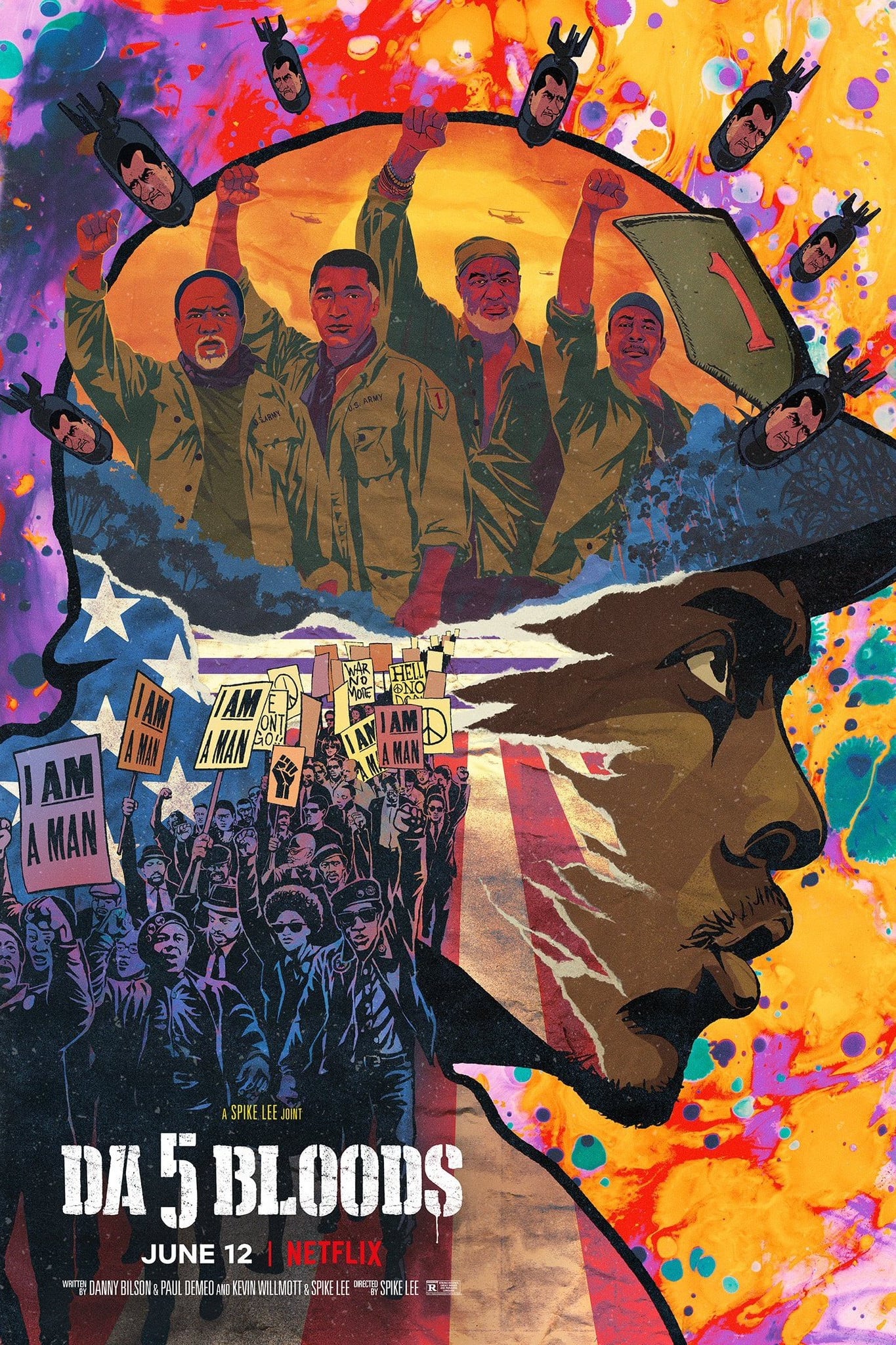

Spike Lee is a director uniquely disinclined to repeat himself, and he's not really repeating himself with Da 5 Bloods, his first feature-length film made by and for Netflix (which is by no means the way I'd prefer to see it). But he is re-running an experiment. The film is a whole lot of things (name the Lee film that isn't), but the heart of it is a corrective to the history of films abut the American war in Vietnam, reading back into the record the service of African-American draftees into a conflict in which they served at a remarkably disproportionate rate. This was virtually the same idea that drove Lee's previous war film, the 2008 Miracle at St. Anna, which did the same for African-Americans in World War II, right down to the preoccupation with correcting the cinematic record specifically (which is, to be sure, a trait of ultra-cinephile Lee beyond just these two movies). The two films also share the trait of going down so many rabbit holes that this central motivating force ends up being somewhat lost beneath the accumulation of ideas (which is also, to be sure, a trait of a great many Lee films).

I would suggest that out of all Spike Lee joints, the dull and forgettable Miracle at St. Anna is the one that it would be least worth revisiting, so the first piece of good news is that Da 5 Bloods is incontestably more interesting. It's not always necessarily better: the film makes more than its share of miscalculations, and with an extraordinarily luxurious running time of 154 minutes, it is able to make them at great leisure. Still, one never goes into a Lee film hoping for trim, efficient filmmaking, but for the vigor and potency of the ideas he's going to be playing with this time, both stylistically and thematically, and Da 5 Bloods most certainly does not want for ideas.

The film began its life as a script written by Danny Wilson & Paul De Meo for director Oliver Stone (whose own iconic Vietnam movie, Platoon, isn't specifically called up as a touchstone, though it was presumably one of the things Lee had in mind), and was re-written by Lee & Kevin Willmott to bring in the racial history; in either case, it's explicitly "what if The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was set in Vietnam?", complete with a "we don't need no steenkin' badges" moment that either Wilson & De Meo or Lee & Wilmott, or all four, should be extremely embarrassed by. The situation is that, some 50 years ago, the Five Bloods - a squad consisting of Paul (Delroy Lindo), Otis (Clarke Peters), Eddie (Norm Lewis), and Melvin (Isiah Whitlock, Jr.), under the leadership of "Stormin'" Norman (Chadwick Boseman) - found a downed CIA plane in the Vietnamese jungle while on patrol, full of gold intended as payment to a local population in exchange for fighting the Viet Cong. The plane was subsequently buried in a napalm strike, and Norman ended up dead. Now, the much older remaining Bloods have discovered thanks to the magic of Google Maps that the plane has re-emerged; they regroup to return to the jungle, along with Paul's son David (Jonathan Majors), both to find the treasure and recover Norman's remains.

If that doesn't sound like two and a half hours of material, the film doesn't pretend otherwise. Da 5 Bloods is made up substantially out of asides and longueurs, enough so that the main story, properly speaking, doesn't start until about an hour in, and has mostly ended by a point about 50 minutes later. Everything else breaks largely into one of two categories: moments where the film stops cold to provide mini-lectures on various aspects of African-American history, particularly as it involves the military; and shaggy narrative dog-ends where moments spin out, allowing the characters to just hang out. The former of these work considerably better: there's anger and passion forcing these asides into the movie, evident in the precision of the language as well as the formal aggression with which they're introduced, generally as still images cut right into the movie without any pretense of fitting in with the movie's diegesis. The brute-force artlessness with which these little lectures are worked into the movie feels like part of the argument, as though the importance of putting this information into the world is underlined by how much it disrupts the movie.

As for the shaggy narrative dog-ends, well, they are what they are. How much of this is a holdover from the original white people version of the script is impossible to say, but it's hard not to feel like the most productive and exciting and righteous material gets buried underneath the sheer quantity of extraneous material. Sometimes this is in the form of meandering extensions of scenes that already do some kind of work, like the Bloods' arrival in Ho Chi Minh City; sometimes it is meandering extensions of scenes that don't really need to be there, like an extensive scene with a Vietnamese farmer trying to sell a chicken. Sometimes, it is entire subplots that have absolutely no function in the film at all, like the arrival of white European anti-land mine activists played by Mélanie Thierry, Paul Walter Hauser, and Jasper Pääkkönen, who combine for not one single interesting or productive scene. Sometimes, it's the way that the film brutally shifts genres in its second half to become something so far afield from the light tragicomic tone and political messaging that it's hard to understand why in God's name anybody ever thought it was the right choice to glue it onto the film, especially since it turns a film that has already all but mentioned Rambo: First Blood, Part II by name as an example of the kind of outrageous pro-imperial propaganda that Da 5 Bloods is looking to fight against into something very like a Rambo clone.

When it's working though, the film is pretty terrific. It has an amazing set of actors inhabiting the characters, breathing warmth into the friendship and fury into the more pointed dialogues about racism and militarism. They're good enough to overcome some pretty shaky writing - one thing the film does not get around to doing with its 154 minutes is to give Otis, Eddie, or Melvin any real definition, but Peters, Lewis, and Whitlock are so specific in how they move and talk and think that the men emerge with distinctive personalities anyway. Gifted with the one substantial character in the film, Lindo gives what is easily one of the best performances of his career: Paul is designed to be as complicated and tough to parse as possible, a Trump-supporting African-American who has more of a keenly-tuned sense of social outrage than the rest of the characters, and a terrifyingly short temper. A lot of love and attention has been lavished on Paul in the writing, and Lindo adds a deep well of solemn despair that makes the character richer still.

He's the strongest element of a film with a lot of peaks and a lot of valleys. The film is trying a lot of things: using the old actors, without any makeup, to play the young versions of themselves, a cost-saving measure that doubles as a way of creating a fuzzier relationship between present and past; using hot yellow 16mm full-frame footage to evoke the past and flat green digital photography in a mix of 1.85:1 and 2.39:1 aspect ratios for the present (I confess to finding the cinematography, by Newton Thomas Sigel, rather cheap-looking and ugly); plus the aforementioned genre-switching and the cornucopia of different plot elements that are trying to diagnose different aspects of post-Vietnam life for veterans, both those with a significant racial component and those without. Some of these things work, and some do not, and I suspect that no two viewers would agree on exactly where to draw that line (for myself, I really liked the "old actors playing young" gimmick that has proven, predictably, to be one of the most controversial parts of the whole). Still, it doesn't feel like you could pull any of it out: like every proper Spike Lee film, the extraordinary messiness seems to be a necessary precursor to getting us to the parts that are great. And while Da 5 Bloods is far from the director's best film, when it's working, it's working damn well.

I would suggest that out of all Spike Lee joints, the dull and forgettable Miracle at St. Anna is the one that it would be least worth revisiting, so the first piece of good news is that Da 5 Bloods is incontestably more interesting. It's not always necessarily better: the film makes more than its share of miscalculations, and with an extraordinarily luxurious running time of 154 minutes, it is able to make them at great leisure. Still, one never goes into a Lee film hoping for trim, efficient filmmaking, but for the vigor and potency of the ideas he's going to be playing with this time, both stylistically and thematically, and Da 5 Bloods most certainly does not want for ideas.

The film began its life as a script written by Danny Wilson & Paul De Meo for director Oliver Stone (whose own iconic Vietnam movie, Platoon, isn't specifically called up as a touchstone, though it was presumably one of the things Lee had in mind), and was re-written by Lee & Kevin Willmott to bring in the racial history; in either case, it's explicitly "what if The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was set in Vietnam?", complete with a "we don't need no steenkin' badges" moment that either Wilson & De Meo or Lee & Wilmott, or all four, should be extremely embarrassed by. The situation is that, some 50 years ago, the Five Bloods - a squad consisting of Paul (Delroy Lindo), Otis (Clarke Peters), Eddie (Norm Lewis), and Melvin (Isiah Whitlock, Jr.), under the leadership of "Stormin'" Norman (Chadwick Boseman) - found a downed CIA plane in the Vietnamese jungle while on patrol, full of gold intended as payment to a local population in exchange for fighting the Viet Cong. The plane was subsequently buried in a napalm strike, and Norman ended up dead. Now, the much older remaining Bloods have discovered thanks to the magic of Google Maps that the plane has re-emerged; they regroup to return to the jungle, along with Paul's son David (Jonathan Majors), both to find the treasure and recover Norman's remains.

If that doesn't sound like two and a half hours of material, the film doesn't pretend otherwise. Da 5 Bloods is made up substantially out of asides and longueurs, enough so that the main story, properly speaking, doesn't start until about an hour in, and has mostly ended by a point about 50 minutes later. Everything else breaks largely into one of two categories: moments where the film stops cold to provide mini-lectures on various aspects of African-American history, particularly as it involves the military; and shaggy narrative dog-ends where moments spin out, allowing the characters to just hang out. The former of these work considerably better: there's anger and passion forcing these asides into the movie, evident in the precision of the language as well as the formal aggression with which they're introduced, generally as still images cut right into the movie without any pretense of fitting in with the movie's diegesis. The brute-force artlessness with which these little lectures are worked into the movie feels like part of the argument, as though the importance of putting this information into the world is underlined by how much it disrupts the movie.

As for the shaggy narrative dog-ends, well, they are what they are. How much of this is a holdover from the original white people version of the script is impossible to say, but it's hard not to feel like the most productive and exciting and righteous material gets buried underneath the sheer quantity of extraneous material. Sometimes this is in the form of meandering extensions of scenes that already do some kind of work, like the Bloods' arrival in Ho Chi Minh City; sometimes it is meandering extensions of scenes that don't really need to be there, like an extensive scene with a Vietnamese farmer trying to sell a chicken. Sometimes, it is entire subplots that have absolutely no function in the film at all, like the arrival of white European anti-land mine activists played by Mélanie Thierry, Paul Walter Hauser, and Jasper Pääkkönen, who combine for not one single interesting or productive scene. Sometimes, it's the way that the film brutally shifts genres in its second half to become something so far afield from the light tragicomic tone and political messaging that it's hard to understand why in God's name anybody ever thought it was the right choice to glue it onto the film, especially since it turns a film that has already all but mentioned Rambo: First Blood, Part II by name as an example of the kind of outrageous pro-imperial propaganda that Da 5 Bloods is looking to fight against into something very like a Rambo clone.

When it's working though, the film is pretty terrific. It has an amazing set of actors inhabiting the characters, breathing warmth into the friendship and fury into the more pointed dialogues about racism and militarism. They're good enough to overcome some pretty shaky writing - one thing the film does not get around to doing with its 154 minutes is to give Otis, Eddie, or Melvin any real definition, but Peters, Lewis, and Whitlock are so specific in how they move and talk and think that the men emerge with distinctive personalities anyway. Gifted with the one substantial character in the film, Lindo gives what is easily one of the best performances of his career: Paul is designed to be as complicated and tough to parse as possible, a Trump-supporting African-American who has more of a keenly-tuned sense of social outrage than the rest of the characters, and a terrifyingly short temper. A lot of love and attention has been lavished on Paul in the writing, and Lindo adds a deep well of solemn despair that makes the character richer still.

He's the strongest element of a film with a lot of peaks and a lot of valleys. The film is trying a lot of things: using the old actors, without any makeup, to play the young versions of themselves, a cost-saving measure that doubles as a way of creating a fuzzier relationship between present and past; using hot yellow 16mm full-frame footage to evoke the past and flat green digital photography in a mix of 1.85:1 and 2.39:1 aspect ratios for the present (I confess to finding the cinematography, by Newton Thomas Sigel, rather cheap-looking and ugly); plus the aforementioned genre-switching and the cornucopia of different plot elements that are trying to diagnose different aspects of post-Vietnam life for veterans, both those with a significant racial component and those without. Some of these things work, and some do not, and I suspect that no two viewers would agree on exactly where to draw that line (for myself, I really liked the "old actors playing young" gimmick that has proven, predictably, to be one of the most controversial parts of the whole). Still, it doesn't feel like you could pull any of it out: like every proper Spike Lee film, the extraordinary messiness seems to be a necessary precursor to getting us to the parts that are great. And while Da 5 Bloods is far from the director's best film, when it's working, it's working damn well.